- This page was last modified on 1 January 2026, at 00:05. Suggest an edit.

al-Hafiz facts for kids

| al-Hafiz li-Din Allah | |

|---|---|

Gold dinar of al-Hafiz, minted at Alexandria in 1149

|

|

| Imam–Caliph of the Fatimid Caliphate | |

| Reign | 23 January 1132 – 10 October 1149 |

| Predecessor | al-Amir bi-Ahkam Allah |

| Successor | al-Zafir bi-Amr Allah |

| Born | 1074/5 or 1075/6 Ascalon |

| Died | 10 October 1149 (aged 72-75) Cairo |

| Issue |

|

| Dynasty | Fatimid |

| Father | Abu'l-Qasim Muhammad ibn al-Mustansir Billah |

| Religion | Isma'ilism |

Abūʾl-Maymūn ʿAbd al-Majīd ibn Muḥammad ibn al-Mustanṣir, known by his royal name al-Ḥāfiẓ li-Dīn Allāh (meaning "Keeper of God's Religion"), was an important ruler in ancient Egypt. He was the eleventh Fatimid caliph, ruling over Egypt from 1132 until his death in 1149. He was also the 21st Imam for a group called Hafizi Isma'ilism.

Al-Hafiz first became powerful as a regent (someone who rules for a king or queen who is too young or sick) after his cousin, al-Amir bi-Ahkam Allah, died in 1130. Al-Amir had only a baby son, Abu'l-Qasim al-Tayyib, who was too young to rule. So, al-Hafiz, being the oldest living family member, became the regent. The baby, al-Tayyib, disappeared, and some believe he was removed from power. Soon after, the army, led by a man named Kutayfat, took control. Kutayfat put al-Hafiz in prison and tried to end the Fatimid rule.

However, Kutayfat's rule didn't last long. He was killed by people loyal to the Fatimid family in December 1131. Al-Hafiz was then set free and became regent again. On January 23, 1132, al-Hafiz declared himself the rightful Isma'ili Imam and Caliph. This was unusual because the title usually passed from father to son. Even though his claim was accepted in Egypt, many Isma'ili followers in other places did not agree. They believed al-Tayyib was the true Imam, which caused a big split in their religion, known as the Hafizi–Tayyibi schism.

Al-Hafiz's time as ruler was full of challenges. He faced many uprisings and power struggles, even from within his own family. He tried to control his powerful ministers, called viziers, but it was difficult. His reign was mostly peaceful with other countries, though there were some conflicts with the Kingdom of Jerusalem near Ascalon. He also kept in touch with rulers in Syria and King Roger II of Sicily, who was expanding his power into former Fatimid lands.

Contents

Early Life and Interests

Al-Hafiz was born as Abd al-Majid in Ascalon around 1074 or 1075. His father was Abu'l-Qasim Muhammad, a son of the ruling Fatimid caliph, al-Mustansir. He was also known as Abu'l-Maymun. We don't know much about his early life before he became a ruler. As an adult, he was known for being smart and calm. He liked collecting things and was very interested in alchemy (an old form of chemistry) and astronomy (the study of stars and planets). He even hired several astronomers to work for him.

Becoming Regent and Imprisonment

On October 7, 1130, Caliph al-Amir bi-Ahkam Allah was killed. He had only a six-month-old son, Abu'l-Qasim al-Tayyib, and no one had been chosen to rule for him. Al-Amir's death put the future of the Fatimid family in danger.

At this time, Abd al-Majid was the oldest living male in the family. Two of al-Amir's close friends, Hazarmard and Barghash, who had influence over the army, teamed up with Abd al-Majid. They wanted to control the government. Abd al-Majid was to become the regent, and Hazarmard would be the vizier. Hazarmard hoped to become a very powerful minister, like a sultan, while Abd al-Majid might have supported him to gain the throne for himself.

As the leader, Abd al-Majid used the title "walī ʿahd al-muslimīn," which meant regent. It's not clear who he was ruling for. Most sources say that the baby al-Tayyib's existence was kept secret, and he disappeared from history. Some scholars think al-Tayyib might have died as a baby. However, one source from that time claims he was killed on Abd al-Majid's orders.

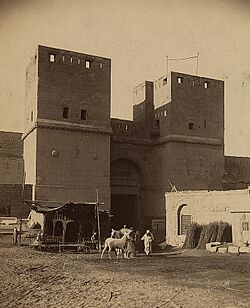

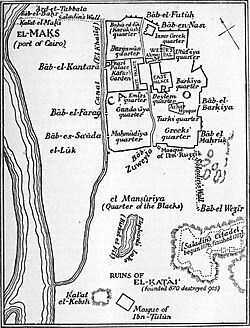

A map of Fatimid-era Cairo, showing the layout of the city and the palaces

The plans of the new leaders quickly changed. About two weeks after al-Amir's death, the army rebelled. They demanded that Kutayfat, the son of a powerful former vizier, become the new vizier. The palace was taken over, Hazarmard was executed, and Kutayfat became vizier on October 21. Abd al-Majid was formally still regent, but he was held prisoner in the palace. Soon, Kutayfat declared that the Fatimid family was no longer in charge and changed the state religion. He claimed to be the representative of a special, hidden spiritual leader. This was seen by many as a move towards Twelver Shi'ism, a different branch of Islam.

Becoming Caliph and Religious Split

The Fatimid leaders did not accept Kutayfat's changes. Members of al-Amir's guards killed Kutayfat in a counter-rebellion on December 8, 1131. Abd al-Majid was freed from prison. This event was celebrated every year as the 'Feast of Victory'.

Since there was no direct heir, Abd al-Majid first continued as regent. However, for the Fatimid family and their religious leadership to continue, he had to become the Imam and Caliph. This is because, in their belief, "God does not leave the Muslim Community without an Imam to lead them." So, on January 23, 1132, Abd al-Majid took the title al-Ḥāfiz li-Dīn Allāh ('Keeper of God's Religion'). This was the first time in the Fatimid family that power did not pass directly from father to son. To explain this, al-Hafiz claimed that al-Amir had secretly chosen him as his successor.

Al-Hafiz's unusual way of becoming Caliph was accepted by most Isma'ili followers in Egypt and nearby areas. However, some groups, especially in Yemen, refused to recognize him. They believed that al-Tayyib, the infant son of al-Amir, was the true Imam. This disagreement led to a major split in the Isma'ili religion, creating the Hafizi and Tayyibi branches. This was not just a political issue; it was deeply religious because the Imam's role was central to their faith.

By 1132, the Isma'ili movement had split into three main groups: the Hafizi (who followed al-Hafiz), the Tayyibi (who followed al-Tayyib), and the Nizari (who had split earlier). The Hafizi branch was tied to the Fatimid rule in Egypt and disappeared after the Fatimid Caliphate ended in 1171. The Tayyibi and Nizari branches still exist today.

Al-Hafiz's Rule

Al-Hafiz becoming Caliph brought back the Fatimid family's power, but the events before had weakened their rule. The new Caliph had little control over the army, and his reign was marked by constant problems. He had to deal with rebellions and challenges from powerful military leaders and even his own family. To make his rule stronger, al-Hafiz used religious festivals to celebrate the Fatimid family. Despite his weak position, al-Hafiz managed to stay in power for almost 20 years.

Al-Hafiz continued the practice of appointing viziers to run the government. However, these viziers had become very powerful, sometimes even threatening the Caliph. Al-Hafiz paid close attention to their actions. For the last ten years of his rule, he did not appoint any viziers. Instead, he relied on high-ranking clerks to manage government affairs.

Early Years and Military Actions (1132–1134)

Al-Hafiz's first vizier was an Armenian named Yanis. Yanis was a former military slave and a key figure in the army groups that had brought Kutayfat to power. Yanis had held important positions before and was very powerful. To strengthen his own authority, he created his own private army. The Caliph became worried about Yanis's growing power. When Yanis died in late 1132, it was rumored that al-Hafiz had him poisoned.

After Yanis's death, the powerful position of vizier was left empty on purpose. Al-Hafiz also removed Yuhanna ibn Abi'l-Layth, who had been in charge of financial administration for a long time. The Caliph used this chance to gain support from families who claimed to be descendants of Muhammad.

At the same time, al-Hafiz wanted to show that the Fatimids were strong Muslim leaders. He restarted attacks against the Christian Crusader states from their base at Ascalon. The Crusaders responded by building new castles like Chastel Arnoul (1133) and Ibelin (1141) to protect their lands. These fortresses made it harder for the Fatimids to attack.

Viziers from Al-Hafiz's Sons (1134–1135)

In 1134, al-Hafiz appointed his own son and chosen successor, Sulayman, as vizier. This was meant to make the family stronger, but it went wrong when Sulayman died two months later. This made people doubt the Caliph's judgment. Sulayman's younger brother Haydara was then named as the next heir and vizier. However, this made another of al-Hafiz's sons, Hasan, very jealous.

Hasan gained the support of a powerful army group, the Juyūshiyya. The Caliph and Haydara were supported by another army group, the Rayḥaniyya. This disagreement also seemed to have religious reasons, as Hasan and his followers were said to support Sunnism and attack Isma'ili preachers. On June 28, Hasan's army defeated Haydara's, forcing Haydara to flee to the palace. Hasan's troops then surrounded the palace. Faced with this difficult situation, al-Hafiz gave in and appointed Hasan as vizier and heir on July 19.

Hasan's rule became very harsh. He created his own private army and used it to scare important people. Al-Hafiz tried to get the Black African army in Upper Egypt to remove his son, but Hasan's men won again. In the end, Hasan's cruel rule led to his downfall. His harsh treatment of enemies and taking people's property made him lose all support. It is said that many people were harmed during Hasan's rule.

After several army commanders were killed, the army rebelled in March 1135. Hasan fled to the palace, where al-Hafiz had him arrested. The troops then gathered outside the palace and demanded that Hasan be removed from power, threatening to burn the palace if their demands were not met. Al-Hafiz called for help from the governor of the western Nile Delta, Bahram al-Armani. Before Bahram could arrive, the Caliph agreed to the soldiers' demands and had his son removed from power.

Bahram's Vizierate (1135–1137)

Political map of the Levant around 1140

Bahram al-Armani, who was a Christian, arrived in Cairo soon after Hasan's removal. He was named vizier on April 4, 1135, and given the title 'Sword of Islam'. Appointing a Christian as vizier caused a lot of opposition among Muslims. This was because the vizier was seen as the Caliph's representative and had important roles in Islamic ceremonies. Al-Hafiz allowed Bahram to skip these religious ceremonies, and the chief judge took his place.

Muslims continued to oppose Bahram because he favored Christians, allowed churches to be built, and encouraged Armenian people to move to Egypt. His brother, Vasak, was made governor of Qus in Upper Egypt, and people at the time said his government was unfair to the local population.

In foreign policy, Bahram's time as vizier brought peace. The Crusader states were busy dealing with a growing threat from a Turkish leader named Zengi. Bahram even helped release 300 prisoners who had been held since a battle in 1102. The vizier also seemed to have good relations with King Roger II of Sicily.

Meanwhile, Muslim opposition to Bahram grew. His position as vizier was already seen as an insult. His favoritism towards Christians, the Armenian immigration, and his close ties with Christian rulers made people even angrier. Ridwan ibn Walakhshi, who had once guarded al-Hafiz in prison, became the leader of this movement. Ridwan was a Sunni Muslim and a powerful military commander. Bahram tried to send him away to govern Ascalon, but Ridwan used this opportunity to block Armenian immigration, which made him popular in Cairo. Ridwan was then sent to govern another province, where he gained an independent power base. Officials in Cairo started contacting him, and Ridwan began preaching against Bahram.

Finally, in early 1137, Ridwan gathered an army and marched on Cairo. Bahram's Muslim soldiers left him, and on February 3, Bahram fled Cairo with 2,000 Armenian soldiers. After he left, there were attacks against Armenians in the capital, and even the vizier's palace was looted.

Bahram eventually retreated to a monastery near Akhmim. Al-Hafiz offered him a deal: he could choose a governorship or enter a monastery with protection for himself and his family. Bahram chose the monastery.

Ridwan's Rule (1137–1139)

Al-Hafiz's kindness towards Bahram makes sense because the Christian vizier was not as big a threat as the Sunni Ridwan ibn Walakhshi. Ridwan, who took office on February 5, 1137, became very powerful. He was called 'Most Excellent King', showing that he was almost like a ruler independent of the Caliph. This showed how much power the Fatimid viziers had gained, becoming like sultans.

As vizier, Ridwan started persecuting Christians. Christian officials were replaced with Muslims, their property was taken, and some were executed. Strict rules were put in place for Christians and Jews, such as requiring them to wear specific clothes and to get off their animals when passing a mosque. The tax they paid was also changed to make them feel inferior. Bahram's Armenian troops were disbanded. At the same time, Ridwan promoted Sunnism, a different branch of Islam. He also talked with rulers in Syria about working together against the Crusaders. In 1138, al-Hafiz made major improvements to the al-Azhar Mosque in Cairo.

In 1138, Ridwan tried to remove al-Hafiz from power completely. He asked religious scholars if al-Hafiz could be removed. Their answers were different: some said al-Hafiz's claim was false, others supported him, and one said it should follow religious law. Ridwan started arresting and executing people close to the Caliph. Al-Hafiz, in response, brought Bahram back from exile and allowed him to stay in the palace. Ridwan then appeared in public wearing clothes usually only worn by monarchs.

Things came to a head on June 8. Al-Hafiz and Ridwan had a heated argument. Ridwan then ordered troops to surround the palace and tried to put one of the Caliph's sons on the throne. But the palace remained closed, and a religious leader insisted that only the Imam could choose his successor. This allowed al-Hafiz to regain control. The son who had sided with Ridwan was killed. On June 12, a group of guards entered the city shouting "al-Hafiz, the Victorious!" They were quickly joined by the people and most of the army, who rebelled against Ridwan. Ridwan managed to escape the city through the Bab al-Nasr (Victory Gate). His palace was looted by the angry crowd.

Ridwan fled to Syria and returned to Egypt with an army of Turkish soldiers. He marched on Cairo but was pushed back from the city gates on August 28, 1139. A month later, al-Hafiz led his army to defeat Ridwan's forces. Ridwan fled but soon had to surrender to the Caliph's forces. Al-Hafiz had Ridwan imprisoned in the palace, in the room next to Bahram's.

Al-Hafiz's Personal Rule (1139–1149)

After Ridwan's fall, al-Hafiz offered to make Bahram vizier again, but Bahram refused. He remained al-Hafiz's close helper. When Bahram died in November 1140, al-Hafiz attended his funeral in person. For the rest of his rule, al-Hafiz did not appoint another vizier. Instead, he chose secretaries to lead the government. This was a deliberate attempt to stop the vizier's office from becoming too powerful. Unlike viziers, these secretaries were civilian officials without ties to the army, and they depended entirely on the Caliph.

The first of these secretaries was an Egyptian Christian named Abu Zakari. He had been in charge of financial offices under Bahram. Al-Hafiz brought him back to his position. However, in 1145, he was arrested and executed on the Caliph's orders. His two successors were Muslim judges.

In foreign affairs, al-Hafiz's last ten years were mostly peaceful. Both the Fatimids and the Kingdom of Jerusalem were dealing with their own problems. In 1142/3, Fatimid messengers visited the court of Roger II of Sicily. Roger was expanding his power into North Africa, which used to be Fatimid land. Despite this, relations remained friendly. A trade agreement was even made between Egypt and Sicily in 1143.

In 1139/40, al-Hafiz sent messengers to the ruler of Aden in Yemen to formally recognize him as a religious leader for Yemen. Another embassy to Yemen happened in 1144. In September 1147, a Fatimid embassy arrived in Damascus, trying to form an alliance against Zengi's son, Nur al-Din. However, Egypt's ongoing internal problems made any Fatimid involvement in Syria impossible.

The last years of al-Hafiz's rule were marked by internal challenges that showed how unstable his power was. In 1144/5, one of al-Hafiz's uncles tried to take the caliphate, but al-Hafiz had him imprisoned. In 1146, a commander rebelled in Upper Egypt but was defeated. In May 1148, Ridwan managed to escape from prison. He gathered followers and marched on Cairo, defeating the Caliph's troops and chasing them into the city. Al-Hafiz closed the palace gates but pretended to cooperate. At the same time, he sent ten Black African guards to kill Ridwan. They attacked and killed him and his brother near the Aqmar Mosque.

In 1149, another person claiming to be a son of Nizar gathered supporters and attacked Alexandria. The rebels won a victory against the first army sent against them. However, the rebellion ended when al-Hafiz bribed the rebel leaders with money and land. The pretender was killed. In 1149, rival army groups clashed in the streets of Cairo, making people afraid to enter the capital. These years also saw natural disasters. The Nile floods were very low in 1139, and there was famine and disease in 1142. In 1148, the Nile flood was too high, reaching the gates of Cairo.

Death and What He Left Behind

Al-Hafiz died on October 10, 1149, from a severe stomach illness. It was remarkable that he survived on the throne through all the threats he faced. He had managed to bring back some of the Caliph's personal control over the government, something not seen for a century. But when he died, he left behind a very unstable government. The Fatimid empire had shrunk to just Egypt and parts of Yemen and Makuria. While the Fatimid cause was weakening, outside Egypt, new powerful Sunni Muslim rulers were rising in Syria. Egypt would soon become a prize in the conflict between these new rulers and the Crusaders, leading to the final end of the Fatimid family.

Al-Hafiz was followed by his youngest and only surviving son, 16-year-old Abu Mansur Isma'il, who took the royal name al-Zafir bi-Amr Allah. Al-Hafiz was the last Fatimid caliph who became ruler as an adult. The next three Fatimid Caliphs, until the end of the family in 1171, were mostly puppet rulers, with real power held by their viziers.

Sources

- Bianquis, Thierry (2002). "al-Ẓāfir bi-Aʿdāʾ Allāh". The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume XI: W–Z. Leiden: E. J. Brill. 382–383. DOI:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_SIM_8067.

- Canard, Marius (1965). "Fāṭimids". The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume II: C–G. Leiden: E. J. Brill. 850–862. DOI:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_COM_0218.

- Canard, Marius (1971). "Ibn Maṣāl". The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume III: H–Iram. Leiden: E. J. Brill. 868. DOI:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_SIM_3288.

- Daftary, Farhad (2007). [Al-Hafiz at Google Books The Ismāʿı̄lı̄s: Their History and Doctrines] (Second ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-61636-2. Al-Hafiz at Google Books.

- Dedoyan, Seta B. (1997). [Al-Hafiz at Google Books The Fatimid Armenians: Cultural and Political Interaction in the Near East]. Leiden, New York, and Köln: Brill. doi:10.1163/9789004492646. ISBN 90-04-10816-5. Al-Hafiz at Google Books.

- Güner, Ahmet (1997). "Hâfız-Lidînillâh". TDV Encyclopedia of Islam, Vol. 15 (Hades – Hanefî Mehmed). Istanbul: Turkiye Diyanet Foundation, Centre for Islamic Studies. 108–110.

- Halm, Heinz (2014) (in de). [Al-Hafiz at Google Books Kalifen und Assassinen: Ägypten und der vordere Orient zur Zeit der ersten Kreuzzüge, 1074–1171]. Munich: C. H. Beck. ISBN 978-3-406-66163-1. Al-Hafiz at Google Books.

- Madelung, W. (1971). "Imāma". The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume III: H–Iram. Leiden: E. J. Brill. 1163–1169. DOI:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_COM_0369.

- Magued, A. M. (1971). "al-Ḥāfiẓ". The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume III: H–Iram. Leiden: E. J. Brill. 54–55. DOI:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_SIM_2612.

- Walker, Paul E. (2017). "al-Ḥāfiẓ li-Dīn Allāh". Encyclopaedia of Islam, THREE. Brill Online. DOI:10.1163/1573-3912_ei3_COM_30176.

|

al-Hafiz

Fatimid dynasty

Born: 1074/5 or 1075/6 Died: 8 October 1149 |

||

| Vacant

Temporary abolition of the Fatimid regime by Kutayfat

Title last held by

al-Amir bi-Ahkam Allah |

Fatimid Caliph 23 January 1132 – 10 October 1149 |

Succeeded by al-Zafir bi-Amr Allah |

| Imam of Hafizi Isma'ilism 23 January 1132 – 10 October 1149 |

||