Albert Schatz (scientist) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

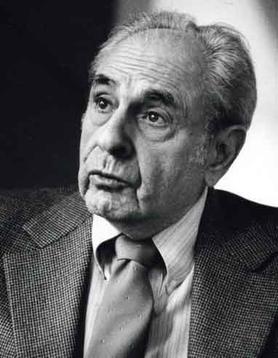

Albert Schatz

|

|

|---|---|

Albert Schatz

|

|

| Born |

Albert Israel Schatz

2 February 1920 |

| Died | 17 January 2005 (aged 84) Philadelphia, USA

|

| Alma mater | Rutgers University |

| Known for | Discoverer of streptomycin Deprived of credit for discovery, leading to change in US laws |

| Spouse(s) | Vivian Schatz (née Rosenfeld, married 1945) |

| Children | Linda Schatz Diane Klein |

| Awards | 1994 Rutgers University Medal |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Microbiology Science education |

| Institutions | Brooklyn College National Agricultural College in Doylestown University of Chile Washington University in St. Louis Temple University |

| Author abbrev. (botany) | A.Schatz |

Albert Israel Schatz (born February 2, 1920 – died January 17, 2005) was an American microbiologist and teacher. He is famous for discovering streptomycin. This was the first antibiotic that could successfully treat tuberculosis, a serious lung disease.

Schatz earned his bachelor's degree in soil microbiology from Rutgers University in 1942. He then completed his PhD there in 1945. His important research during his PhD led directly to the discovery of streptomycin.

Born into a farming family, Albert Schatz was interested in soil science. He hoped it would help him with farming. After graduating at the top of his class, he worked with Selman Waksman, a leading soil microbiologist. Albert Schatz also helped discover another antibiotic called albomycin in 1947.

The discovery of streptomycin led to some disagreements. There were issues over who should get money from the medicine and who should receive the Nobel Prize. Schatz was not aware that Waksman had claimed most of the money for himself. Schatz later filed a lawsuit. He was then granted 3% of the money and was officially recognized as a co-discoverer.

In 1952, the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was given only to Waksman for discovering streptomycin. Many felt this was unfair to Schatz. Later, in 1994, Rutgers University honored Schatz with the Rutgers University Medal.

Contents

Early Life and Learning

Albert Schatz was born in Norwich, Connecticut, in the United States. He went to school in Passaic, New Jersey. His parents, Julius and Rae Schatz, were farmers who had moved from Russia and England.

In 1932, he started studying at the College of Agriculture at Rutgers State University of New Jersey. He graduated with honors in soil science in 1942. The very day he got his results, he began working with Selman Waksman. Waksman was the head of the Department of Soil Microbiology at Rutgers.

Since 1937, Waksman's team had been looking for new antibiotics from tiny living things in soil. Between 1940 and 1952, they found more than 10 such chemicals. A fellow student, Doris Ralston, described Schatz as a "brilliant student" who worked very hard.

Schatz first worked on antibiotics like actinomycin, clavacin, and streptothricin. He soon found that these were too harmful to animals to be used as medicines for people. After five months, he joined the US Army in December 1942 during World War II.

Because he knew about microbiology, he worked as a bacteriologist in army hospitals in Florida. He left the army in June 1943 due to a back injury. Schatz decided to pursue a PhD instead of working for a drug company. He rejoined Waksman's lab and earned his PhD in 1945. His PhD work led to the discovery of streptomycin.

Discovery of Streptomycin

When Schatz returned to Waksman's lab in 1943, he wanted to find an antibiotic that could fight certain types of bacteria. At that time, there was no good medicine for infections caused by these bacteria.

A doctor named William Hugh Feldman suggested that Waksman look for antibiotics to fight tuberculosis. However, Waksman was worried about working with Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the bacteria that causes tuberculosis, because it was very dangerous.

Schatz insisted that he wanted to research a tuberculosis drug, and Waksman agreed. Feldman gave Schatz a very strong strain of the tuberculosis bacteria. Waksman made sure Schatz worked alone in the lab's basement. He also ordered that the bacteria samples should never leave the basement.

Within three and a half months, Schatz found two types of bacteria called Streptomyces griseus. These bacteria produced substances that stopped the growth of tuberculosis bacteria. One type came from a healthy chicken's throat, and the other from soil.

Schatz worked day and night. He even slept on a wooden bench in the lab. He wanted to make streptomycin quickly so Feldman could test it. On October 19, Schatz saw that his extract killed the tuberculosis bacteria. He named it "streptomycin."

Schatz, along with Elizabeth Bugie and Waksman, announced their discovery in a journal in January 1944. The new compound worked against many types of bacteria, including the human tuberculosis bacteria.

In 1944, Schatz and his lab mates showed that streptomycin worked in mice with tuberculosis. By 1946, tests in the UK and USA proved streptomycin could treat TB, bubonic plague, cholera, and other diseases. Schatz prepared all the original samples for these tests himself.

Patent and Legal Issues

Waksman knew it would be hard to get a patent for streptomycin. US law made it difficult to patent natural products. However, with help from lawyers, he argued that the new compound was different. The patent office agreed.

In 1946, Schatz and Waksman agreed to receive a small payment for their invention. This was so that Rutgers University, not individuals, would benefit. Schatz agreed to give his rights to the money from the patent to the Rutgers Research and Endowment Foundation.

The US Patent Office granted the patent for streptomycin to Schatz and Waksman in 1948. A company called Merck got the right to make the medicine. Elizabeth Bugie, who helped with the discovery, was not included in the patent. Waksman thought she would "just get married."

Schatz soon felt that Waksman was not giving him enough credit. In 1949, it became known that Waksman had a secret agreement. He was getting 20% of the money from the patent, while the Rutgers foundation got 80%.

In March 1950, Schatz sued Waksman and the foundation. He wanted a share of the money and recognition for his role. Bugie supported Schatz. In December 1950, the court ruled in favor of Schatz. The court said Schatz was a "co-discoverer" of streptomycin.

As a result, Schatz received $120,000 for foreign patent rights. He also got 3% of the money from the medicine, which was about $15,000 each year for several years. Waksman received 10%, and 7% was shared among other workers in Waksman's lab. Rutgers used its 80% share to create the Waksman Institute of Microbiology.

Later Career

After leaving Rutgers in 1946, Schatz worked at Brooklyn College and the National Agricultural College in Doylestown, Pennsylvania. From 1953, much of his work focused on dentistry.

While working at the Philadelphia General Hospital, Schatz and his uncle developed a theory about what causes tooth decay. This theory was published in 1962.

Schatz became a distinguished professor at the University of Chile from 1962 to 1965. He then taught education at Washington University in St. Louis from 1965 to 1969. From 1969 to 1980, he was a professor of science education at Temple University. In Chile, he studied the effects of adding fluoride to drinking water.

Personal Life

Albert Schatz's first interest in soil microbiology came from wanting to be a farmer, like his parents. Seeing workers treated badly during the Great Depression made him a lifelong supporter of social justice and helping others. He married Vivian Rosenfeld in March 1945. They had two daughters, Linda and Diane.

Awards and Honors

Schatz received special degrees from universities in Brazil, Peru, Chile, and the Dominican Republic. In 1994, on the 50th anniversary of streptomycin's discovery, he received the Rutgers University Medal.

The New York Times newspaper listed Schatz and Waksman's 1948 streptomycin patent as one of the top 10 discoveries of the 20th century. Rutgers University has turned Schatz's basement lab into a museum. It shows his work and other antibiotic discoveries made there.

Legacy

Because of the issues surrounding streptomycin, new rules were made in the US. These rules help make sure that students who contribute to discoveries get proper recognition and rewards. Albert Schatz's personal papers and records were given to the Temple University Library.

See also

- Nobel Prize controversies

| Tommie Smith |

| Simone Manuel |

| Shani Davis |

| Simone Biles |

| Alice Coachman |