Aldo Leopold facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Aldo Leopold

|

|

|---|---|

Leopold in 1946

|

|

| Born | January 11, 1887 Burlington, Iowa, U.S. |

| Died | April 21, 1948 (aged 61) Baraboo, Wisconsin, U.S. |

| Resting place | Aspen Grove Cemetery Burlington, Iowa, U.S. |

| Occupation | |

| Education | Yale University |

| Subject | Conservation, land ethic, land health, ecological conscience |

| Notable works | A Sand County Almanac |

| Spouse | Estella Leopold |

| Children | A. Starker Leopold, Luna B. Leopold, Nina Leopold Bradley, A. Carl Leopold, Estella Leopold |

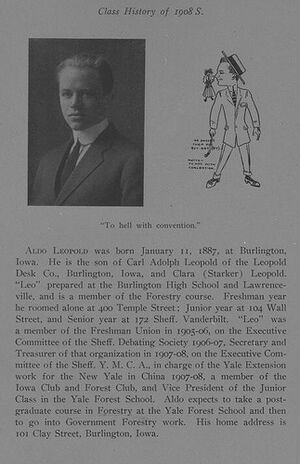

Aldo Leopold (born January 11, 1887 – died April 21, 1948) was an important American writer and scientist. He loved nature and worked to protect it. He taught at the University of Wisconsin. Leopold is famous for his book A Sand County Almanac. This book has sold millions of copies and is about caring for the Earth. He helped start the idea of modern environmental ethics. This means thinking about how we treat nature. He also helped create the science of wildlife management. This is about managing wild animals and their homes.

Contents

Early Life and Nature's Call

Aldo Leopold was born in Burlington, Iowa, on January 11, 1887. His father, Carl Leopold, was a businessman. Aldo's family included his younger siblings, Mary Luize, Carl Starker, and Frederic. Aldo's first language was German, but he learned English quickly.

Aldo spent a lot of time outdoors when he was young. His father often took him and his siblings into the woods. He taught Aldo about nature and hunting. Aldo loved to watch and count birds near his home. His sister Mary said he was "very much an outdoorsman" even as a child. He explored the bluffs and the river. Every summer, his family went to Marquette Island in Lake Huron, Michigan. The children loved exploring the forests there.

Schooling and Forestry Dreams

In 1900, Gifford Pinchot helped start one of the first forestry schools in the U.S. at Yale University. When Aldo was a teenager, he heard about this and decided he wanted to be a forester. His parents sent him to The Lawrenceville School in New Jersey. This was a special school to help him get into Yale.

Aldo arrived at Lawrenceville in January 1904, just before his 17th birthday. He was a good student, but he was still drawn to the outdoors. Lawrenceville was in the countryside, so Aldo spent time mapping the area. He also studied the local wildlife. After a year, he was accepted into Yale. Since the Yale School of Forestry was for graduate students, he first studied forestry as an undergraduate. He graduated from the Yale Forestry School in 1909.

Career in Conservation

After college, Leopold joined the United States Forest Service in 1909. He worked in Arizona and New Mexico. He helped create the first plan for managing the Grand Canyon. He also wrote the Forest Service's first guide for game and fish.

One of his biggest achievements was suggesting the Gila Wilderness Area in New Mexico. This became the first national wilderness area in the Forest Service system. A wilderness area is a place where nature is protected and left wild.

In 1924, Leopold moved to Madison, Wisconsin. He became an associate director at the U.S. Forest Products Laboratory.

In 1933, he became a professor at the University of Wisconsin. He taught about wildlife management. This was the first time a university had a professor just for this subject. He also became the Research Director of the University of Wisconsin–Madison Arboretum. Here, he worked to bring back "original Wisconsin" landscapes. This included prairies and oak forests that were there before European settlers arrived.

In 1935, Leopold visited forests in Germany and Austria. He learned about how they managed their forests. He saw that planting only one type of tree in straight lines could harm the soil and reduce different kinds of plants and animals. This trip helped him think more deeply about ecology.

Family Life and Legacy

Aldo Leopold married Estella Bergere in 1912. They had five children. Their children also became teachers and naturalists, following in their father's footsteps.

- A. Starker Leopold (1913–1983) was a wildlife biologist.

- Luna Leopold (1915–2006) was a hydrologist (someone who studies water).

- Nina Leopold Bradley (1917–2011) was a researcher and naturalist.

- A. Carl Leopold (1919–2009) was a plant scientist.

- Estella Leopold (1927–2024) was a botanist (someone who studies plants).

Leopold bought 80 acres of land in central Wisconsin. This land had been logged and damaged by fires and grazing. He used this land to test his ideas about restoring nature. He worked on his famous book, A Sand County Almanac, there. He finished the book just before he died.

Aldo Leopold died on April 21, 1948, from a heart attack while fighting a wildfire on a neighbor's property. He is buried in Aspen Grove Cemetery in Burlington, Iowa. Today, his home in Madison is a city landmark.

Leopold's Important Ideas

Early in his career, Leopold was told to hunt and kill predators like bears, wolves, and mountain lions. Ranchers disliked these animals because they sometimes harmed livestock. But over time, Leopold began to respect these predators.

One day, after shooting a Mexican wolf, he saw a "fierce green fire dying in her eyes." This moment changed him. He realized that predators were important for a healthy ecosystem. He began to think about nature in a new way. He believed that humans should not try to control nature, but instead be a part of it. His ideas helped bring back bears and mountain lions to wilderness areas in New Mexico.

By the 1920s, Leopold thought that certain parts of national forests should be kept wild. He saw how more roads and cars were changing public lands. He was the first to use the word "wilderness" to describe these protected areas. He believed it was easier to keep wilderness wild than to try and create it later. He asked, "Of what avail are forty freedoms without a blank spot on the map?" He felt that people should respect the land, not just use it for their own benefit.

In the 1930s, Leopold became one of the first Americans to write a lot about wildlife management. He said that wildlife habitats should be managed scientifically. This meant working with both public and private landowners. He believed this was better than just having game refuges or hunting laws. In his 1933 book Game Management, he said it was "the art of making land produce sustained annual crops of wild game for recreational use." But he also saw it as a way to bring back and keep different kinds of plants and animals in the environment.

Leopold's idea of "wilderness" also changed. It was no longer just a place for hunting or recreation. It became a place for a healthy natural community, including wolves and mountain lions. In 1935, he helped start the Wilderness Society. This group works to protect wilderness areas. He saw the society as a place for "a new attitude—an intelligent humility toward Man's place in nature."

Nature Writing and A Sand County Almanac

Leopold's nature writing is known for being clear and direct. He wrote about natural places he knew well. He showed how much he understood what happens in nature. He kept detailed journals about his work and experiences. He also wrote about his farm in Sand County.

He often criticized the harm done to natural systems. He felt that people often acted as if they owned the land. This ignored the idea that humans are part of a larger community of life. He believed that modern machines give people time to think about how special nature is. They can also learn more about it.

A Sand County Almanac

This book was published in 1949, after Leopold's death. One of the most famous quotes from the book explains his land ethic:

A thing is right when it tends to preserve the integrity, stability, and beauty of the biotic community. It is wrong when it tends otherwise. (p.262)

In the chapter "Thinking Like a Mountain", Leopold talks about the idea of a trophic cascade. This is when changes at one level of an ecosystem affect other levels. He realized that killing a predatory wolf had serious effects on the whole ecosystem. This idea was appreciated by many people later on.

In January 1995 I helped carry the first grey wolf into Yellowstone, where they had been eradicated by federal predator control policy only six decades earlier. Looking through the crates into her eyes, I reflected on how Aldo Leopold once took part in that policy, then eloquently challenged it. By illuminating for us how wolves play a critical role in the whole of creation, he expressed the ethic and the laws which would reintroduce them nearly a half-century after his death.

The Land Ethic

In "The Land Ethic" chapter of A Sand County Almanac, Leopold talks about conservation. He wrote: "Conservation is a state of harmony between men and land." He felt that conservation rules at the time were too simple. They just said to obey laws and practice conservation if it was profitable.

Leopold explained his idea:

The land ethic simply enlarges the boundaries of the community to include soils, waters, plants, and animals, or collectively: the land.

This sounds simple: do we not already sing our love for and obligation to the land of the free and the home of the brave? Yes, but just what and whom do we love? Certainly not the soil, which we are sending helter-skelter down river. Certainly not the waters, which we assume have no function except to turn turbines, float barges, and carry off sewage. Certainly not the plants, of which we exterminate whole communities without batting an eye. Certainly not the animals, of which we have already extirpated many of the largest and most beautiful species. A land ethic of course cannot prevent the alteration, management, and use of these 'resources,' but it does affirm their right to continued existence, and, at least in spots, their continued existence in a natural state. In short, a land ethic changes the role of Homo sapiens from conqueror of the land-community to plain member and citizen of it. It implies respect for his fellow-members, and also respect for the community as such.

He believed that the land ethic makes us see land as part of our community. It includes soils, water, plants, and animals. This means we should respect them and allow them to exist in a natural state. It changes humans from being conquerors of the land to being members of its community.

Leopold's Lasting Impact

Aldo Leopold's ideas continue to be very important today.

- In 1950, The Wildlife Society created an award in his name.

- The Aldo Leopold Foundation was started in 1982 by his children. It works to spread Leopold's land ethic. The foundation owns and manages the Aldo Leopold Shack and Farm. This is where Leopold lived and worked on his ideas. They also have the Leopold Center, which teaches about conservation.

- In 2012, a film about Leopold called Green Fire: Aldo Leopold and a Land Ethic for Our Time was released. It won an Emmy award.

Many places and organizations are named after him:

- The Aldo Leopold Wilderness in New Mexico was named after him in 1980.

- The Leopold Center for Sustainable Agriculture was created in 1987 at Iowa State University. It works on new ways to farm that protect nature.

- The U.S. Forest Service started the Aldo Leopold Wilderness Research Institute in 1993. It studies how to manage wilderness and protected areas.

- Leopold's former home in Albuquerque is a historic landmark.

- The Aldo Leopold Legacy Trail System in Wisconsin has 42 state trails.

An organization called the Leopold Heritage Group works to promote Aldo Leopold's legacy in his hometown of Burlington, Iowa.

Works

- Report on a Game Survey of the North Central States (1931)

- Game Management (1933)

- A Sand County Almanac (1949)

- Round River: From the Journals of Aldo Leopold (1953)

- A Sand County Almanac and Other Writings on Ecology and Conservation (2013)

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Aldo Leopold para niños

In Spanish: Aldo Leopold para niños

- Grey Owl

- Timeline of environmental events

- Land Ethic

- Sand County Foundation

- Yale School of Forestry & Environmental Studies

- Aldo Leopold Legacy Trail System

- Aldo Leopold Wilderness

- Leopold Wetland Management District

- Ian McTaggart-Cowan

- J. Drew Lanham

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |