Alphonse Mucha facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Alphonse Mucha

|

|

|---|---|

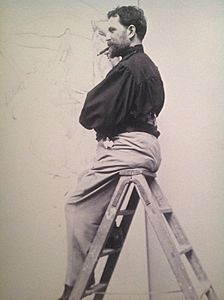

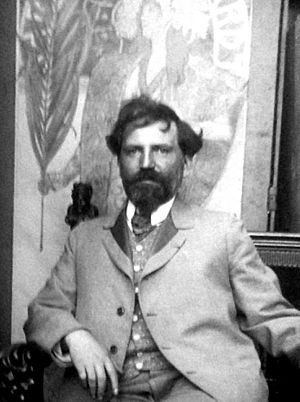

Mucha in his studio (c. 1899)

|

|

| Born |

Alfons Maria Mucha

24 July 1860 Ivančice, Margraviate of Moravia, Austrian Empire

|

| Died | 14 July 1939 (aged 78) Prague, Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia

|

| Education | Munich Academy of Fine Arts Académie Julian Académie Colarossi |

| Known for | Painting, illustration, decorative art |

|

Notable work

|

The Slav Epic (Slovanská epopej) |

| Movement | Art Nouveau |

| Awards | Legion of Honor (France), Knight of the Order of Franz Joseph I (Austria) |

| Signature | |

|

|

Alfons Maria Mucha (born July 24, 1860 – died July 14, 1939), known around the world as Alphonse Mucha, was a famous Czech artist. He was a painter, illustrator, and graphic designer. He lived in Paris during the Art Nouveau period, which was a popular art style at the time.

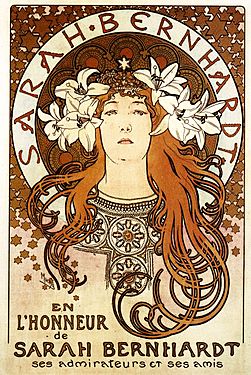

Mucha is best known for his unique and decorative posters for plays, especially those featuring the famous actress Sarah Bernhardt. He also created illustrations, advertisements, and beautiful decorative panels. His designs became some of the most recognizable images of that era.

Later in his life, when he was 57, Mucha went back to his home country. There, he spent many years painting a huge series of twenty canvases called The Slav Epic. These paintings tell the story of all the Slavic peoples of the world. He worked on them from 1912 to 1926. In 1928, he gave this important series to the Czech nation to celebrate 10 years of Czechoslovakia's independence. He believed this was his most important work.

Contents

- Early Life and Artistic Beginnings

- Studying in Munich and Paris

- Sarah Bernhardt and Gismonda

- Commercial Art and Decorative Panels

- Decorative Panels Gallery

- 1900 Paris Universal Exposition

- Jewelry and Collaboration with Fouquet

- Documents Decoratifs and Teaching

- Le Pater

- Travels to America and Marriage

- Move to Prague and The Slav Epic (1910–1928)

- Last Years and Death

- Legacy

- See Also

Early Life and Artistic Beginnings

Alphonse Mucha was born on July 24, 1860, in a small town called Ivančice. This area was part of the Austrian Empire back then, but it's now in the Czech Republic. His family didn't have much money. His father worked for the court, and his mother was a miller's daughter.

Even as a young child, Mucha showed a great talent for drawing. A local shopkeeper was so impressed that he gave Mucha free paper, which was quite a luxury. Mucha also loved music and was a good singer and violin player.

After finishing elementary school, Mucha wanted to continue his education, but his family couldn't afford it. His music teacher helped him try to get into a choir at a monastery to fund his studies. He wasn't accepted there, but he did get into the choir at the Cathedral of St. Peter and Paul, Brno. This allowed him to study at a gymnasium (a type of high school). When his voice changed, he stopped singing in the choir but continued to play the violin during church services.

Mucha was very religious and felt that art, church, and music were all connected. He grew up in a time when Czech people were very proud of their heritage, and he even designed flyers for patriotic events.

In 1878, he tried to get into the Academy of Fine Arts, Prague, but they told him to find a different career. So, in 1880, at age 19, he moved to Vienna, the capital of the Austrian Empire. He found a job painting scenery for theaters. In Vienna, he explored museums and theaters, and he was inspired by a famous painter named Hans Makart. Makart's grand historical paintings influenced Mucha's later work. Mucha also started experimenting with photography, which became a useful tool for his art.

In 1881, a big fire destroyed the main theater his company worked for, leaving Mucha almost broke. He traveled to Mikulov and started drawing portraits and decorating tombstones. His work was noticed by Count Eduard Khuen Belasi, a local nobleman. The Count hired Mucha to paint murals for his castles. These paintings showed Mucha's skill with myths, female figures, and beautiful plant designs. Count Belasi also took Mucha to see art in Italy and introduced him to other artists.

Studying in Munich and Paris

Count Belasi helped Mucha go to Munich in September 1885 for formal art training at the Munich Academy of Fine Arts. While there, Mucha became friends with other Slavic artists. He even started a Czech students' club and drew political cartoons for Czech newspapers. He was happy with the artistic environment in Munich, but eventually, foreign students faced more restrictions. Count Belasi suggested he go to Rome or Paris. Mucha chose Paris and moved there in 1887 with the Count's financial help.

In 1888, Mucha enrolled in art schools in Paris, the Académie Julian and the Académie Colarossi. However, by the end of 1889, Count Belasi stopped his financial support, and Mucha, almost 30, was on his own.

Mucha found a place to stay in a boarding house known for helping struggling artists. He decided to become an illustrator for magazines, like his friend Ludek Marold. In the early 1890s, he started drawing for weekly magazines, including La Vie populaire and Le Petit Français Illustré. His illustrations for stories and historical events began to earn him a regular income.

With his new income, he bought a harmonium (a type of organ) and his first camera. He used his camera to take pictures of himself and his friends, and also to help him plan his drawings. He even shared a studio with the famous painter Paul Gauguin for a while. He also became friends with the writer August Strindberg, sharing an interest in philosophy.

His magazine work led to book illustrations. He drew for a history book, and four of his illustrations were shown at the 1894 Paris Salon of Artists, where he won an honor medal. This was his first official recognition. He also illustrated a children's poetry book and a theater magazine.

Sarah Bernhardt and Gismonda

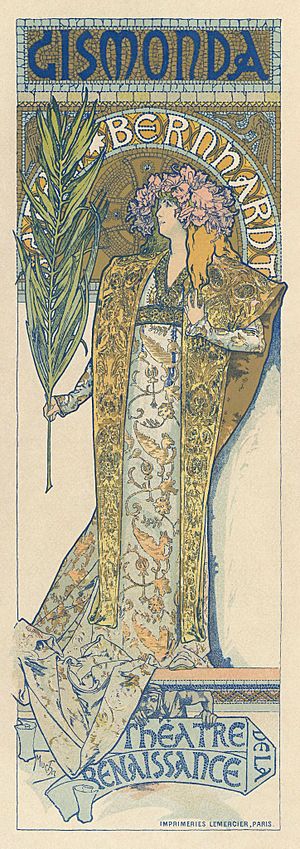

At the end of 1894, Mucha's career changed completely when he started working for the famous French actress Sarah Bernhardt. The story goes that Bernhardt needed a new poster for her play Gismonda very quickly, by January 1, 1895. Because of the holidays, none of the usual artists at the printing company were available.

Mucha happened to be at the printing house correcting some work. He had already drawn Bernhardt before. The manager asked Mucha to design the new poster. The poster was huge, over two meters tall. It showed Bernhardt as a Byzantine noblewoman, wearing a beautiful headdress and holding a palm branch.

One new and special thing about Mucha's posters was the rainbow-shaped arch behind the actress's head, almost like a halo. This drew attention to her face and became a feature in all his future theater posters. The poster used soft, delicate colors, unlike the bright posters common at the time. It looked very elegant.

The Gismonda poster appeared on the streets of Paris on January 1, 1895, and everyone loved it! Bernhardt was so happy that she ordered thousands of copies and gave Mucha a six-year contract to create more posters for her. Suddenly, with his posters all over the city, Mucha became very famous.

After Gismonda, Bernhardt started working with a different printer, F. Champenois, who also signed a six-year contract with Mucha. Champenois had a large printing house and gave Mucha a good monthly salary for the rights to publish all his work. With more money, Mucha moved into a bigger apartment with a large studio.

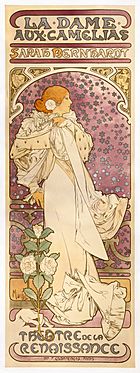

Mucha designed posters for all of Bernhardt's plays, including La Dame aux Camelias (1896), Lorenzaccio (1896), Medea (1898), La Tosca (1898), and Hamlet (1899). He sometimes used photographs of Bernhardt to help him. Besides posters, he also designed play programs, sets, costumes, and even jewelry for her. Bernhardt was smart and sold some of the printed posters to collectors.

-

La Dame aux Camélias (1896)

-

As Hamlet (1899)

Commercial Art and Decorative Panels

Mucha's success with the Bernhardt posters led to many requests for advertising posters. He designed ads for cigarette papers, champagne, biscuits, baby food, chocolate, and even bicycles.

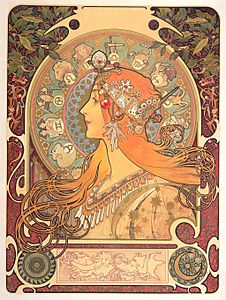

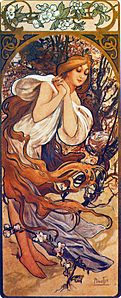

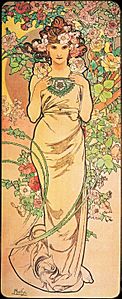

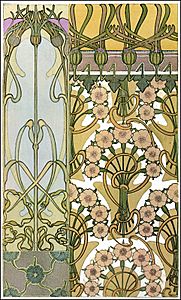

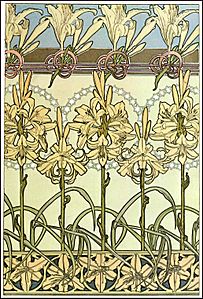

Working with Champenois, he also created something new: decorative panels. These were posters without any text, made purely for decoration. They were printed in large numbers and sold at a fair price. His first series was The Seasons (1896), showing four different women in beautiful floral settings, each representing a season. He also designed a calendar with a woman's head surrounded by zodiac signs, which was very popular.

Over the years, he created other series like The Flowers, The Arts (1898), The Times of Day (1899), Precious Stones (1900), and The Moon and the Stars (1902). Between 1896 and 1904, Mucha designed over a hundred posters for Champenois. These were sold in different ways, from expensive versions on special paper to cheaper versions, calendars, and postcards.

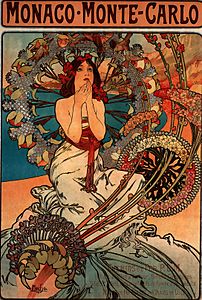

His posters almost always featured beautiful women in fancy settings, with their hair often swirling in decorative patterns that filled the whole picture. For example, his poster for the train line between Paris and Monaco-Monte-Carlo (1897) didn't show a train or the places. Instead, it showed a beautiful young woman surrounded by swirling floral designs, which hinted at the train's turning wheels.

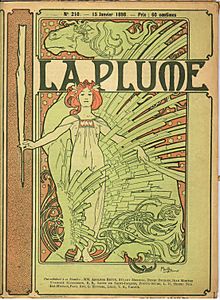

His famous posters brought him recognition in the art world. He was invited to show his work in exhibitions and had a big show in 1897 with 448 of his pieces. A magazine even dedicated a special issue to his art. His exhibition traveled to many cities around the world, making him internationally famous.

Decorative Panels Gallery

1900 Paris Universal Exposition

The Paris Universal Exposition of 1900 was a huge world's fair that showed off the new Art Nouveau style. This gave Mucha a chance to try something different: large historical paintings, which he had always admired. It also allowed him to show his Czech pride.

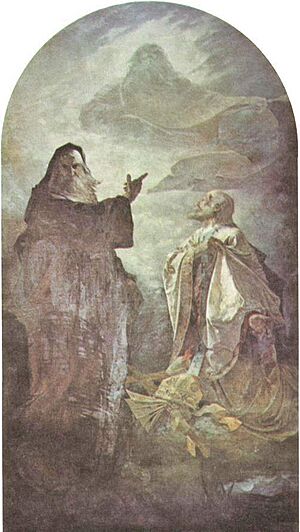

He was hired by the Austrian government to create murals for the Pavilion of Bosnia and Herzegovina. This pavilion showed off the culture and industry of these regions, which were then under Austrian rule. Mucha's original idea was to show the suffering of the Slavic people under foreign rule, but the Austrian government wanted something more positive for a world's fair. So, he changed his plan to show a future where different religions and cultures in the Balkans lived together peacefully.

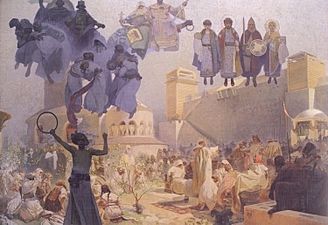

Mucha traveled to the Balkans to sketch costumes, ceremonies, and buildings for his new work. His art included a large painting called Bosnia Offers Her Products to the Universal Exposition, plus other murals showing the history of the region. He quietly included some images of suffering in the upper parts of the murals. He often used photographs of models to help him create his large paintings. Even though the work showed dramatic events, it gave an overall feeling of peace. Mucha also designed the menu for the Bosnia Pavilion's restaurant.

His work was seen in many places at the Exposition. He designed posters for Austria's part in the fair and menus for official events. He also created displays for a jeweler and a perfume maker, featuring statues and panels of women representing different scents. His more serious artworks were shown in the Austrian Pavilion.

Because of his work at the Exposition, Mucha received important awards: the Knight of the Order of Franz Joseph from Austria and the Legion of Honour from France. During the Exposition, Mucha also suggested that the Eiffel Tower, which was built for the fair and was supposed to be taken down, should have a monument to humanity built on top of it. But the Eiffel Tower was so popular that it stayed!

Jewelry and Collaboration with Fouquet

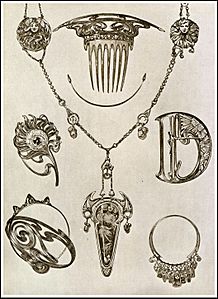

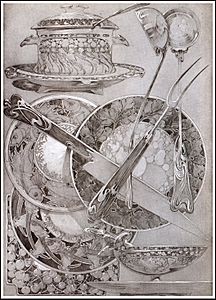

Mucha was interested in many forms of art, including jewelry. His 1902 book, Documents Decoratifs, showed detailed designs for brooches and other pieces. These designs featured swirling patterns and plant shapes, often with colorful enamel and stones.

In 1899, he worked with a jeweler named Georges Fouquet to create a special bracelet for Sarah Bernhardt. It was shaped like a serpent, made of gold and enamel, similar to jewelry she wore in her play Medea. This spiraling snake design was a nod to Mucha's famous swirling Art Nouveau painting style. He also designed a beautiful "Cascade pendant" for Fouquet in 1900, shaped like a waterfall with gold, enamel, opals, and diamonds.

After the 1900 Exposition, Fouquet decided to open a new jewelry shop in Paris and asked Mucha to design the inside. Mucha's design included two large peacocks made of bronze and wood, which were symbols of luxury. There was also a shell-shaped fountain with statues and carved decorations. The shop was a masterpiece of Art Nouveau design.

The shop opened in 1901, but soon after, art styles began to change. The shop's decorations were taken down in 1923. Luckily, most of the original decorations were saved and are now displayed at the Carnavalet Museum in Paris, where you can still see them today.

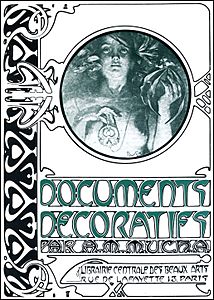

Documents Decoratifs and Teaching

Mucha's next big project was a book called Documents Decoratifs, published in 1902. It contained 72 watercolor plates showing how natural forms like flowers and plants could be used in different types of decoration and objects.

Around 1900, he also started teaching at the Academy Colarossi in Paris, where he had once been a student. His course taught students how to use artistic decoration for panels, windows, porcelain, jewelry, posters, and more.

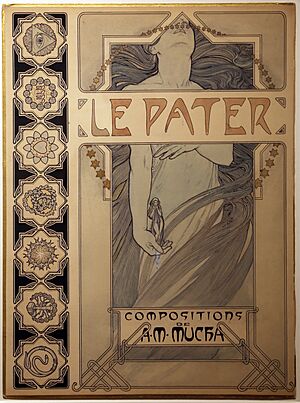

Le Pater

Even though Mucha earned a lot of money from his theater and advertising work, he really wanted to be known as a serious artist and thinker. He was a devoted Catholic but also interested in spiritual ideas.

In 1898, he joined a group called the Freemasons in Paris. Before the 1900 Exposition, he felt that his usual work wasn't truly satisfying. He wanted to create art that spread a deeper message. He decided to illustrate the Pater Noster (the Lord's Prayer).

He suggested to his publisher that the book should have a decorative cover, then variations of that decoration for each line of the prayer, a page explaining each line in beautiful writing, and finally, a picture showing the idea of each line.

Le Pater was published on December 20, 1899, with only 510 copies. The original paintings for the book were shown at the 1900 Exposition. Mucha considered Le Pater his most important printed work. He told a newspaper that he had "put his soul" into it. A critic wrote that the book showed Mucha was a "visionary" with an imagination that people didn't expect from him.

Travels to America and Marriage

In March 1904, Mucha sailed to New York for his first visit to the United States. His main goal was to find money for his huge project, The Slav Epic, which he had planned during the 1900 Exposition. He was already famous in America because his posters had been widely displayed during Sarah Bernhardt's tours there since 1896.

He rented a studio in New York, painted portraits, and gave interviews and lectures. He also connected with groups that supported Slavic people. At one event, he met Charles Richard Crane, a rich businessman who loved Slavic culture. Crane asked Mucha to paint a portrait of his daughter in a traditional Slavic style. More importantly, Crane shared Mucha's excitement for a series of huge paintings about Slavic history and became Mucha's most important supporter. Later, when Mucha designed the Czechoslovak money, he used Crane's daughter as the model for the image of Slavia on the 100 koruna bill.

Mucha wrote to his family that he came to America to escape the constant demands of publishers in Paris and to find a chance to do more meaningful work.

He still had work to finish in France, so he returned to Paris in May 1904. He came back to New York in January 1905 and made four more trips to the U.S. between 1905 and 1910, usually staying for several months. In 1906, he returned to New York with his new wife, Marie Chytilová, whom he had married in Prague on June 10, 1906. They stayed in the U.S. until 1909, and their first child, Jaroslava, was born in New York that year.

His main income in the U.S. came from teaching art and design at various schools, including the New York School of Applied Design for Women and the Art Institute of Chicago. He usually turned down commercial work, but in 1906, he designed boxes and a store display for a soap bar called Savon Mucha. In 1908, he also took on a large project to decorate the inside of the German Theater of New York, creating three large Art Nouveau murals representing Tragedy, Comedy, and Truth.

Artistically, his time in America wasn't his most successful. Portrait painting wasn't his strongest skill, and the German Theater closed soon after it opened. He made posters for American actresses, but they were similar to his Bernhardt posters. His best work from this period is often considered to be the portrait of Josephine Crane Bradley (his patron's daughter) as Slavia, dressed in Slavic costume and surrounded by Slavic symbols. His connection with Charles Crane made his biggest art project, The Slav Epic, possible.

-

Poster of actress Maude Adams as Joan of Arc (1909)

Move to Prague and The Slav Epic (1910–1928)

During his many years in Paris, Mucha never forgot his dream of being a history painter and showing the great achievements of the Slavic people. He finished his plans for The Slav Epic in 1908 and 1909. In February 1910, Charles Crane agreed to pay for the project. In 1909, Mucha was also asked to paint murals inside the new city hall of Prague. He decided to move back to his home country, which was still part of the Austrian Empire at the time. He wrote to his wife, "I will be able to do something truly good, not just for art critics but for our Slav souls."

His first project in 1910 was decorating the reception room for the mayor of Prague. This caused some arguments because local Prague artists felt the work should have gone to them. They reached a compromise: Mucha decorated the Lord Mayor's Hall, and other artists decorated the other rooms. For the Lord Mayor's Hall, he designed and created large murals for the domed ceiling and walls. These showed strong figures in heroic poses, representing the contributions of Slavs to European history and the idea of Slavic unity. These patriotic paintings were very different from his earlier work in Paris.

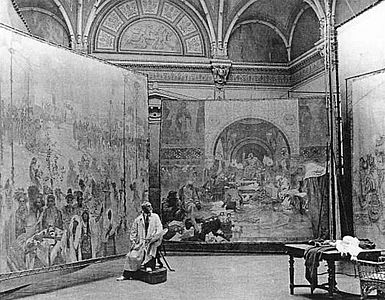

The Lord Mayor's Hall was finished in 1911. Then, Mucha could focus on what he considered his most important work: The Slav Epic. This was a series of twenty huge paintings showing the history and achievements of Slavic peoples. Half of the paintings were about the history of the Czechs, and the other ten were about other Slavic groups like Russians, Poles, Serbs, Hungarians, and Bulgarians. The canvases were enormous, measuring six by eight meters each. To paint them, he rented a studio in Zbiroh Castle in western Bohemia, where he lived and worked until 1928.

Mucha had imagined the series as "light shining into the souls of all people." To prepare for the project, he traveled to all the Slavic countries, from Russia to the Balkans, making sketches and taking photographs. He used models in costumes and even motion picture cameras to set up his scenes. He used a special type of paint called egg tempera, which he believed dried faster, looked brighter, and would last longer.

He created the twenty canvases between 1912 and 1926. He continued working through World War I, even though it was hard to get canvas due to wartime rules. He kept working after the war ended and the new Czechoslovak Republic was formed. The entire series was finished in 1928, just in time for the tenth anniversary of Czechoslovakia's independence.

As part of his agreement, he gave his completed work to the city of Prague in 1928. The Slav Epic was shown in Prague twice during his lifetime, in 1919 and 1928. After 1928, it was rolled up and stored away for many years.

From 1963 until 2012, the series was displayed in a castle in Moravský Krumlov in the Czech Republic. In 2012, it was moved to the National Gallery's Veletržní Palace in Prague. In 2021, it was announced that a new, permanent home for the paintings would be built in central Prague, expected to be ready by 2026.

While working on The Slav Epic, Mucha also did work for the new Czech government. In 1918, he designed the korun banknotes, using the image of Slavia, based on the daughter of his American supporter, Charles Crane. He also designed postage stamps for his new country. He generally turned down commercial work but occasionally made posters for charity and cultural events.

Making of The Slav Epic

- The Slav Epic

Last Years and Death

In the 1930s, the political situation in Czechoslovakia was difficult, and Mucha's work didn't get much attention. However, in 1936, a big exhibition of his art was held in Paris, showing 139 of his works, including three from The Slav Epic.

As Hitler and Nazi Germany began to threaten Czechoslovakia in the 1930s, Mucha started a new series of paintings. He worked on a triptych (a three-part painting) about the Age of Reason, the Age of Wisdom, and the Age of Love from 1936 to 1938, but he never finished it. On March 15, 1939, the German army marched into Prague, and Hitler declared that Czechoslovakia was now part of Germany.

Because Mucha was known as a Czech nationalist and a Freemason, he became a target. He was arrested and questioned for several days before being released. By then, his health was very poor. He got pneumonia and died on July 14, 1939, just ten days before his 79th birthday and a few weeks before World War II began. Even though public gatherings were banned, a huge crowd attended his burial at the Slavín Monument in Vyšehrad cemetery, a special place for important Czech cultural figures.

Legacy

Mucha was, and still is, best known for his Art Nouveau work. This actually frustrated him because he didn't think much of the term "Art Nouveau," saying, "Art can never be new." He was most proud of his historical paintings.

Even though his art is very popular today, at the time of his death, Mucha's style was considered old-fashioned. His son, Jiří Mucha, spent much of his life writing about his father and bringing attention to his artwork. In his own country, the new authorities weren't very interested in Mucha. The Slav Epic was rolled up and stored for 25 years before it was finally shown again. The National Gallery in Prague now displays The Slav Epic and has the largest collection of his works.

Mucha is also recognized for helping to bring back the movement of Czech Freemasonry.

One of the largest collections of Mucha's works belongs to Ivan Lendl, a former world-famous tennis player. He started collecting Mucha's art after meeting Jiří Mucha in 1982. His collection was shown publicly for the first time in Prague in 2013.

See Also

In Spanish: Alfons Mucha para niños

In Spanish: Alfons Mucha para niños

- Art Nouveau posters and graphic arts

- List of works by Alphonse Mucha

- Les Maîtres de l'Affiche

- Salon des Cent