Alton B. Parker facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Alton B. Parker

|

|

|---|---|

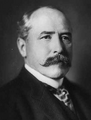

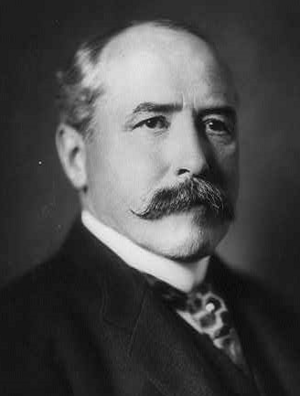

Parker in 1906

|

|

| Chief Judge of the New York Court of Appeals | |

| In office January 1, 1898 – August 5, 1904 |

|

| Preceded by | Charles Andrews |

| Succeeded by | Edgar M. Cullen |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Alton Brooks Parker

May 14, 1852 Cortland, New York, U.S. |

| Died | May 10, 1926 (aged 73) New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Resting place | Wiltwyck Cemetery, Kingston, New York |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouses | Mary Schoonmaker Amy Day Campbell |

| Education | Union University, New York (LLB) |

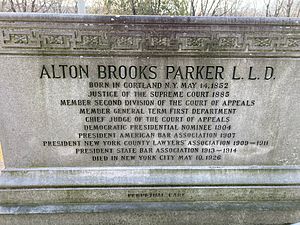

Alton Brooks Parker (born May 14, 1852 – died May 10, 1926) was an American judge. He is best known for being the Democratic candidate who lost the 1904 presidential election to Theodore Roosevelt.

Parker grew up in upstate New York. He worked as a lawyer in Kingston, New York. Later, he became a judge on the New York Supreme Court. He was then elected to the New York Court of Appeals. From 1898 to 1904, he served as the Chief Judge of this court. He left this job to run for president.

In 1904, Parker won the Democratic Party nomination for President. He beat William Randolph Hearst, a well-known publisher. In the main election, Parker ran against the very popular Republican President Theodore Roosevelt. Parker's campaign was not well organized. He lost the election by a large number of votes. He only won states in the traditionally Democratic Solid South. After the election, he went back to being a lawyer. He also helped with other political campaigns in New York.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Parker was born in Cortland, New York. His parents, John Brooks Parker and Harriet F. Stratton, were well educated. They encouraged him to read from a young age. When he was about 12 or 13, Parker watched his father serve on a jury. He was so interested that he decided to become a lawyer.

He went to Cortland Academy and later worked as a teacher. He met Mary Louise Schoonmaker and they got engaged. After graduating from the State Normal School in Cortland, Parker married Mary in 1872. He then worked at a law firm where one of her relatives was a senior partner. He studied law at Albany Law School at Union University. In 1873, he earned his law degree. He then practiced law in Kingston until 1878.

Parker also became active in the Democratic Party. He supported Grover Cleveland, who later became Governor of New York and U.S. President. Parker was a delegate at the 1884 Democratic National Convention. Cleveland was chosen as the presidential candidate there. Parker also became a close helper to David B. Hill, managing Hill's campaign for governor in 1885.

Becoming a Judge

After David B. Hill was elected governor, he appointed Parker to fill an empty spot on the New York Supreme Court in 1885. In 1886, Parker was elected to serve a fourteen-year term in that position. Three years later, Parker became an appeals judge. Hill appointed him to a new part of the Appellate Division. In November 1897, Parker successfully ran for the top job of Chief Judge of the Court of Appeals. He beat Republican William James Wallace.

As a judge, Parker was known for carefully researching each case himself. He was generally seen as supportive of workers' rights. He also backed laws that aimed to improve society. For example, he supported a law that set a maximum number of working hours.

While he was Chief Judge, Parker and his wife moved to an estate in Esopus on the Hudson River. They called their home "Rosemount." They had two children, Bertha and John. Sadly, John died as a child. Bertha later married Charles Mercer Hall and had two children.

Important Cases as a Judge

- In the case of Hamer v. Sidway (1891), Parker decided that if someone gives up a legal right because of a promise, that promise can be a valid part of a contract.

- In Roberson v. Rochester Folding Box Co (1902), Parker ruled against a teenager whose face was used in ads without her permission. This decision was not popular. It led to a new privacy law being passed in New York the next year.

Running for President

As the 1904 presidential election got closer, the Democrats looked for someone to run against the popular Republican President Theodore Roosevelt. Alton B. Parker's name came up as a possible candidate. Roosevelt's Secretary of War, Elihu Root, said Parker "has never opened his mouth on any national question." But Roosevelt worried that Parker's neutral stance might actually be an advantage.

The 1904 Democratic National Convention was held in July in St. Louis, Missouri. Parker's mentor, David B. Hill, worked hard to get him nominated. William Jennings Bryan, who had lost the previous two elections, was not seen as a strong choice this time. Some in the party supported publisher William Randolph Hearst, but he did not have enough support.

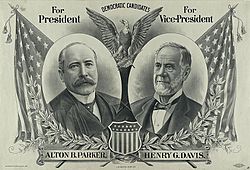

Parker had been a judge for a long time. This helped him get the nomination because he had avoided taking strong sides on issues that divided the party. His supporters kept quiet about his exact beliefs. When the convention voted, it was clear that Parker was the only candidate who could bring the party together. He was chosen on the first vote. Henry G. Davis, an older millionaire from West Virginia, was chosen as the vice presidential candidate. The hope was that he would help pay for Parker's campaign.

There was a big debate at the convention about whether to support "free silver." This idea meant the government would print many silver dollars, which would cause inflation. Farmers in the West liked this idea because it would make their debts easier to pay. But businesses preferred the "gold standard," which meant less inflation. Bryan strongly opposed the gold standard. In the end, the convention decided not to include a clear statement on the issue in their platform.

However, Parker wanted to win over the "sound money" group from the East. As soon as he heard he was nominated, he sent a telegram to the convention. He stated that the gold standard was "firmly and irrevocably established." He said he would refuse the nomination if he couldn't say this during his campaign. This telegram caused another debate, but the convention eventually agreed that Parker could speak his mind on the issue. Support for Parker began to grow. Roosevelt even privately called Parker's telegram "bold and skillful."

The Presidential Campaign

After getting the nomination, Parker left his job as a judge. On August 10, a group of party leaders officially visited him at his home, Rosemount. Parker then gave a speech. He criticized Roosevelt's actions in other countries. He also said Roosevelt had not set a date for the Philippines to become independent. Even Parker's supporters thought the speech was not very exciting. Historians say this speech was a big problem for Parker's campaign. After this, Parker went back to being quiet and avoided commenting on major issues.

Parker's campaign was not well managed. Parker and his team decided to use a "front porch campaign." This meant groups of people would come to Rosemount to hear Parker speak. This method had worked well for McKinley in 1896. However, Esopus was far away, and the campaign did not use its money well to bring visitors. So, Parker did not get many visitors.

Instead of talking about different ideas, the Democrats focused on Roosevelt's personality. They tried to make him seem dangerously unstable. Parker's campaign also failed to connect with groups that usually voted Democratic, like Irish Catholic immigrants. In contrast, Roosevelt's campaign was very organized. It had special groups to reach out to Jewish, Black, and German-American voters.

A month before the election, Parker found out that Roosevelt's campaign was getting a lot of money from big companies. Parker started talking about "Cortelyouism" in his speeches. He accused the president of not being serious about breaking up large business groups (called "trusts"). In late October, he went on a speaking tour in New York and New Jersey. He kept saying that the president was willing to make compromises that hurt his dignity. Roosevelt was very angry and called Parker's criticisms "monstrous" and "slanderous."

However, Parker's attacks came too late to change the election. On November 8, Roosevelt won by a huge margin. He got 7,630,457 votes to Parker's 5,083,880. Roosevelt won every state in the North and West, getting 336 electoral votes. Parker only won states in the traditionally Democratic Solid South, getting 140 electoral votes. That night, Parker sent a telegram to Roosevelt congratulating him. Then, he went back to his private life.

Some historians have said that Parker was a very capable person. They believe the 1904 election was one of the few times voters had two excellent candidates to choose from. But many felt that Americans liked Roosevelt more because of his exciting style.

Later Life and Legacy

After the election, Parker went back to practicing law. He served as the president of the American Bar Association from 1906 to 1907. He represented labor unions in several important cases.

Parker later returned to politics. He managed John Alden Dix's successful campaign for governor in 1910. He also gave the main speech at the 1912 Democratic National Convention, which nominated Woodrow Wilson for president. In 1911, he announced his support for women's suffrage, telling a group of women lawyers that he "most heartily" supported their movement. In 1913, he worked as a lawyer during the process to remove Governor William Sulzer from office.

Parker's first wife, Mary, died in 1917. He married Amelia Day "Amy" Campbell in 1923. On May 10, 1926, Parker died from a heart attack while riding in his car in New York City's Central Park. This was just four days before his 74th birthday. He was survived by his daughter, two grandchildren, and his second wife. He was buried in Wiltwyck Cemetery in Kingston.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Alton B. Parker para niños

In Spanish: Alton B. Parker para niños

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |