Ann Maria Jackson facts for kids

Ann Maria Jackson (born around 1810 – died January 28, 1880) was a brave mother who was enslaved. She had nine children. In November 1858, she ran away from her owner after two of her oldest children were sold. Her husband became very sad and later died. When she found out that four more of her children were about to be sold, she gathered seven of them. They traveled along the Underground Railroad to Canada to find freedom. The Jackson family started new lives in Toronto. Her two oldest children later joined them. Her youngest son, Albert Jackson, became the first African American mail carrier in Toronto.

Contents

Ann Maria's Family Life

Ann Maria Jackson was born around 1810. People described her as kind, smart, and pretty. She was enslaved by a man named James Brown. Ann Maria had nine children with her husband, John Jackson, who was a free blacksmith. They lived in Milford, Delaware.

At that time, a law said that children born to an enslaved mother belonged to her owner. This meant John Jackson had no legal rights over his own children. Ann Maria was allowed to live with her husband when her children were young. This saved her owner, Brown, money because he didn't have to feed the family. Ann Maria worked as a laundress and painted buildings. Brown took a share of her earnings.

As her children grew, they became valuable to Brown. He could hire them out and keep their pay, or he could sell them. Ann Maria said it broke her heart when her children were taken as soon as they were old enough to help her. She worked hard to feed her children. She always worried that her owner could take them away at any moment. For years, she tried to convince her husband to run away with their children. But John didn't think he could make the difficult journey.

In 1858, Ann Maria's two oldest children, James and Richard, were sold away from the family. John was very upset by this. He became very ill and passed away that fall. Soon after, Ann Maria learned that Brown planned to sell four more of her children far away to Vicksburg, Mississippi. She quickly made plans to escape. She wanted to find a place where she could truly care for her children.

The Journey to Freedom

Ann Maria Jackson began her journey with seven of her children in mid-November 1858. Her children were between two and sixteen years old. They traveled along the Underground Railroad. She knew that laws like the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 allowed runaway enslaved people to be caught and returned to their owners. Between 1850 and 1860, many Black people, about 15,000 to 20,000, moved to Canada. Slavery had been ended in Canada in 1834.

It was a very hard trip for the family. It was also difficult for the people helping them on the Underground Railroad. Thomas Garrett, a helper, noted that with young children, they couldn't walk very far. It was also hard to cross a canal near the Maryland-Pennsylvania border because it was watched closely for runaways.

Near Wilmington, Delaware, Thomas Garrett arranged for a horse-drawn carriage. It took them part of the way to Philadelphia. A second carriage then took them across the Mason–Dixon line into the free state of Pennsylvania.

They stopped at the Riverview House, the home of Thomas Garrett's brother Edward. The Jacksons were then taken to Philadelphia. There, they met William Still, who was an important leader on the Underground Railroad. He talked to Ann Maria and her children to write down their stories in his book, Underground Rail Road.

The desire for freedom clearly burned strongly in this enslaved mother. Otherwise, she would never have dared to escape from the horrors of slavery with seven children.

After Philadelphia, they continued their journey through Pennsylvania and New York. They followed a network of Underground Railroad stations. After crossing into Canada West (now Ontario), they arrived in St. Catharines on November 25. There, Hiram Wilson helped them. He then sent them to Toronto with letters for Mrs. Dr. Willis and Thomas Henning of the Anti-Slavery Society of Canada.

I am happy to tell you that Mrs. Jackson and her wonderful family of seven children arrived safely and in good health at my house in St. Catharines on Saturday evening... I was pleased to provide them comfortable rooms until this morning, when they left for Toronto."

—Hiram Wilson wrote in a letter to William Still on November 30, 1859

Starting a New Life in Toronto

In Toronto, Mrs. Willis and Thomas Henning took the Jacksons to the home of Lucie and Thornton Blackburn. The Blackburns had also escaped slavery from Kentucky. They had started the first taxi business in Toronto.

Henning, Willis, and the Blackburns helped the Jacksons find jobs, housing, clothes, and everything they needed to get settled. Ann Maria's children were enrolled in school. Ann Maria supported her family by washing clothes. She rented rooms in St. John's Ward, an area where many immigrants lived. The Toronto House of Industry gave them food and wood shortly after they arrived and again the next winter. Ann Maria was described as "very hardworking." By 1861, they rented a small house in Toronto. It was located at 93 Elizabeth Street, near Osgoode Hall.

James Henry, Ann Maria's oldest son, had run away from Frederica, Delaware. He was about to be sold by his owner, Joseph Brown. James Henry made it to Philadelphia, where he met William Still in September 1858. He then went to St. Catharines. After he learned that his family had come to Canada, he found them in Toronto. Later, Richard M. Jackson, another son, also reunited with the family.

Ann Maria's children grew up and became successful. They worked as barbers, a waiter, and a laundress. Richard started hairdressing businesses with important and wealthy customers. When he died in 1885 at age 38, a thousand people attended his funeral. These included members of the Black community, newspaper publishers, and former city leaders. James Henry worked as a waiter at the Queen's Hotel.

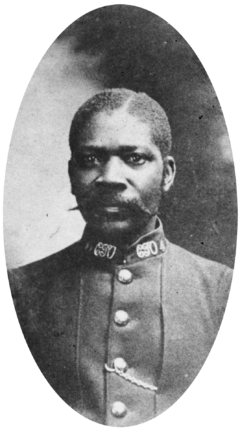

In 1882, Ann Maria's youngest son, Albert, became the first Black mail carrier in Toronto. At first, some postal workers did not want a Black man to have a job that was usually for white workers. Albert was hired to deliver mail, but he was made a mail sorter instead. A public investigation was held to find out why Albert was demoted. After help from Sir John A. Macdonald, Albert began to deliver mail as he was hired to do. He worked as a postal worker for 36 years, retiring in 1918.

Later Life and Passing

Ann Maria Jackson continued to wash and iron clothes until the year before she passed away. She died from a stomach illness at her daughter Mrs. Harry Nelson's home on January 28, 1880. She was 70 years old. Reverend Charles A. Washington gave the sermon at her memorial service. It was held at the old Sayer Street Chapel (now British Methodist Episcopal Church) in St. John's Ward.

Ann Maria Jackson and her son Richard are buried in the Necropolis Cemetery, in the Blackburn family grave. Other Jackson family members are buried in different parts of the cemetery.

Ann Maria's Legacy

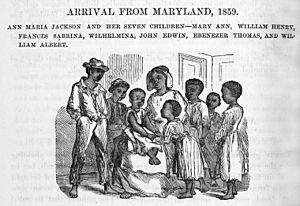

An image of Ann Maria Jackson and her children was published on April 2, 1874. It appeared in newspapers like The Nation, Lutheran Observer, Friends Review, and the New York Daily Tribune. The picture was titled The Father Died in the Poor House, a Raving Maniac, Caused by the Sale of Two of His Children. It was also printed for more than forty weeks in the Christian Recorder. William Still used this and other pictures to promote his book, The Underground Rail Road.

| Chris Smalls |

| Fred Hampton |

| Ralph Abernathy |