Australian giant cuttlefish facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Australian giant cuttlefish |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Giant cuttlefish from Whyalla, South Australia | |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Mollusca |

| Class: | Cephalopoda |

| Order: | Sepiida |

| Family: | Sepiidae |

| Genus: | Sepia |

| Subgenus: | Sepia |

| Species: |

S. apama

|

| Binomial name | |

| Sepia apama Gray, 1849

|

|

|

|

| Distribution of Sepia apama | |

| Script error: The function "autoWithCaption" does not exist. | |

| Synonyms | |

|

|

Script error: No such module "Check for conflicting parameters".

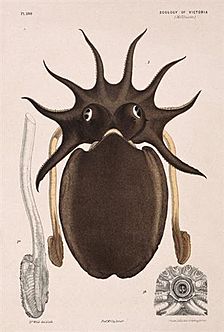

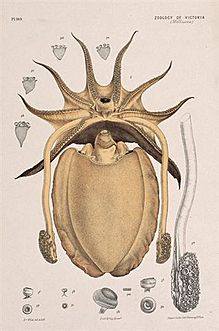

The Giant Cuttlefish, also called the Australian Giant Cuttlefish (scientific name Sepia apama), is the biggest cuttlefish in the world! These amazing creatures can grow up to 50 centimeters (about 20 inches) long in their main body (mantle). If you include their outstretched tentacles, they can reach a total length of 100 centimeters (about 39 inches). They can also weigh over 10.5 kilograms (about 23 pounds).

Giant Cuttlefish are masters of disguise. They use special cells called chromatophores to change their skin color and patterns in a flash. This helps them hide or show off! You can find these cuttlefish in the warm and mild waters around Australia. They live from Brisbane in Queensland all the way to Shark Bay in Western Australia, and down to Tasmania. They like rocky reefs, seagrass beds, and sandy or muddy seafloors, living as deep as 100 meters (about 330 feet). In 2009, they were listed as "Near Threatened" because their numbers seemed to be going down.

Contents

Life of a Giant Cuttlefish

Giant Cuttlefish usually live for only 1 to 2 years. They breed when winter starts in the southern parts of Australia.

How they reproduce

When it's time to breed, male cuttlefish stop trying to blend in. Instead, they put on amazing light shows! They change their colors and patterns very quickly to impress the females. Females often mate with more than one male. They lay their eggs under rocks in caves or hidden spots. The eggs hatch after about three to five months.

Giant Cuttlefish are special because they only breed once in their lives. After they mate and lay their eggs, they usually die soon after. This is because they don't eat much during the breeding season. They slowly lose strength and condition until they pass away.

Most of the time, these cuttlefish breed in pairs or small groups. They lay their eggs in safe places like caves. But there's one amazing exception: hundreds of thousands of them gather in the Upper Spencer Gulf in South Australia! This is a huge breeding party. Young cuttlefish leave these breeding areas after hatching. Scientists don't know much about where they go or what they do as they grow up. Adult cuttlefish usually return to the same breeding spot the next winter.

Amazing Cuttlefish Body and Behavior

Scientists have studied the genes of Giant Cuttlefish. They found that different groups of cuttlefish don't often mix and breed with each other. Even though they are all the same species, they are often known by where they live. For example, there's the "Upper Spencer Gulf population." This group is special because the water in Spencer Gulf is saltier in some parts. This might keep other cuttlefish from living there. Some scientists even think the Upper Spencer Gulf cuttlefish might be a separate species because they look a bit different and have unique behaviors.

What they eat

Giant Cuttlefish are carnivores, meaning they eat other animals. They are also opportunistic and fierce predators. They mostly eat crabs, shrimp, and fish.

How they change color

Cuttlefish have incredible control over their skin. They use three layers of special cells to change color and texture:

- Chromatophores: These are the top layer and can be red to yellow. They change quickly.

- Iridophores: These are in the middle layer and create shiny, iridescent colors like blues and greens. They can even change how reflective they are!

- Leucophores: These are the bottom layer and are white.

These layers work together to create amazing patterns. Cuttlefish are colorblind, but their eyes can see the polarization of light. This means they can see light waves that are lined up in a certain way. This might be how they talk to each other! They can also raise bumps called papillae on their skin. This lets them change their skin's shape and texture to look like rocks, sand, or seaweed.

Daily life

Studies show that Giant Cuttlefish are mostly active during the day. They don't move around much in their daily lives. They spend about 95% of their day resting and hiding in cracks to stay safe from predators. They spend very little time hunting for food. This means they save most of their energy for growing. The only time they are much more active is during their huge breeding gatherings.

Who eats Giant Cuttlefish?

Giant Cuttlefish are a tasty meal for some other ocean animals.

- Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphins: In South Australia, dolphins have learned a clever trick. They remove the ink and the hard cuttlebone from the cuttlefish before eating them!

- Long-nosed fur seals

- Yellowtail kingfish

There have been worries that kingfish that escape from fish farms might eat young cuttlefish or their eggs in Spencer Gulf.

The Special Spencer Gulf Population

Divers first found the huge gathering of Giant Cuttlefish in the Upper Spencer Gulf in the late 1990s. This is the only known place in the world where so many cuttlefish come together to breed. It has become a very popular spot for divers and snorkelers to visit.

Hundreds of thousands of Giant Cuttlefish gather on rocky reefs near Point Lowly, close to Whyalla, between May and August. During the breeding season, there can be up to 11 males for every female! Scientists aren't sure if this means fewer females come to breed, or if males breed for a longer time. The sheer number of cuttlefish here is amazing. They cover about 61 hectares (about 150 acres) and can be as dense as one cuttlefish per square meter.

When they are breeding, the cuttlefish don't seem to notice divers at all. This makes them a major tourist attraction. Professor Roger Hanlon from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution has called this breeding gathering "the premier marine attraction on the planet."

The cuttlefish in the Upper Spencer Gulf have two different ways of growing. Some grow quickly and are ready to breed in seven to eight months. They are smaller adults when they return to spawn for the first time. Others grow slowly and take two years to mature. These adults are larger when they return to breed in their second year.

Because so many cuttlefish gather here, they have unique breeding behaviors. Large males will protect females and the places where eggs are laid. Smaller males, called "sneakers," will pretend to be females to get close to the females being guarded by the big males. The dominant males are very protective of their territory.

Protecting the Cuttlefish

There was an attempt to list this group of Giant Cuttlefish as a threatened species in Australia. This happened because their numbers were going down, and people were worried about pollution from a big mining project nearby. However, in 2011, the government decided not to list them. They said that this group of cuttlefish was not different enough from other Giant Cuttlefish for the law to protect them separately. Still, more recent scientific work suggests that the cuttlefish in northern Spencer Gulf are genetically different from other groups, but these findings haven't been officially published yet.

Fishing for Cuttlefish

Before the mid-1990s, people fished for the Upper Spencer Gulf cuttlefish to use as bait for snapper. They caught about 4 tonnes (4,000 cuttlefish) each year. But in 1995 and 1996, commercial fishing on the breeding grounds increased a lot, with about 200 tonnes caught each year. In 1997, 245 tonnes were caught, which was too much. So, in 1998, half of the breeding grounds were closed to commercial fishing. Even with the closure, fishers still caught 109 tonnes in 1998. By 1999, the catch dropped to only 3.7 tonnes.

The graph below shows how much cuttlefish was caught by commercial fishers in South Australia.

| Financial Year | Tonnes caught |

|---|---|

| 1992–93 |

3

|

| 1993–94 |

7

|

| 1994–95 |

35

|

| 1995–96 |

71

|

| 1996–97 |

263

|

| 1997–98 |

170

|

| 1998–99 |

15

|

| 1999–00 |

16

|

| 2000–01 |

19

|

| 2001–02 |

27

|

| 2002–03 |

11

|

| 2003–04 |

6

|

| 2004–05 |

9

|

| 2005–06 |

8

|

| 2006–07 |

11

|

| 2007–08 |

6

|

| 2008–09 |

4

|

| 2009–10 |

10

|

| 2010–11 |

5

|

| 2011–12 |

3

|

| 2012–13 |

4

|

| 2013–14 |

2

|

Why the numbers dropped

From 1998 to 2001, the number of cuttlefish seemed stable because fishing was reduced. But in 2005, a survey showed a 34% drop since 2001. This was thought to be due to natural changes and illegal fishing. The fishing ban was then made larger to cover all the breeding grounds. People thought numbers increased in 2006 and 2007, but a 2008 survey showed another 17% decrease.

In 2011, only about 33% of the 2010 population returned to breed. That was fewer than 80,000 cuttlefish. Local fishermen said that some commercial fishers were catching the cuttlefish just outside the protected zone before they could reach the breeding grounds. Since cuttlefish only breed once, scientists were worried.

In 2012, the numbers dropped again. A group was formed to study the problem. A tour guide named Tony Bramley, who had been taking divers to see the cuttlefish for years, said it was "heartbreaking" to see so few animals.

The Conservation Council of South Australia warned that the Spencer Gulf cuttlefish could disappear in a few years if nothing was done. The government group suggested an immediate ban on fishing for cuttlefish. However, this was rejected by the government. They said there wasn't strong proof that fishing was causing the problem.

On March 28, 2013, the government put a temporary ban on fishing for cuttlefish in the northern Spencer Gulf for that breeding season. They said research had ruled out commercial fishing as the main cause, but they still didn't know why the numbers had dropped so much. The population kept falling, reaching its lowest numbers ever in 2013.

Good news came in 2014, when the cuttlefish population started to show signs of getting better. Numbers increased again in 2015, confirming this trend. By 2021, the population had recovered to an estimated 240,000 animals!

The fishing ban for the northern Spencer Gulf was extended until 2020. In 2020, the closed area was made smaller again, covering only the waters of False Bay, from Whyalla to Point Lowly and north towards the Point Lowly North marina.

How many cuttlefish are there?

The graph below shows the estimated number of cuttlefish each year.

| Year | Population estimate |

|---|---|

| 1999 |

168,497

|

| 2000 |

167,584

|

| 2001 |

172,544

|

| 2002 |

0

|

| 2003 |

0

|

| 2004 |

0

|

| 2005 |

124,867

|

| 2006 |

0

|

| 2007 |

0

|

| 2008 |

75,173

|

| 2009 |

123,105

|

| 2010 |

104,805

|

| 2011 |

38,373

|

| 2012 |

18,531

|

| 2013 |

13,492

|

| 2014 |

57,317

|

| 2015 |

130,771

|

| 2016 |

177,091

|

| 2017 |

127,992

|

- A '0' means no survey was done that year.

- Data from 1999–2017 is from the SARDI.

Local industry and the cuttlefish

The large cuttlefish breeding areas in the Upper Spencer Gulf are close to several industrial sites. These sites release pollution into the sea. This includes the Whyalla steelworks and the Port Pirie lead smelter. Scientists are concerned about how these might affect the cuttlefish.

Too many nutrients?

The northern Spencer Gulf naturally has low levels of nutrients. But pollution from industries, like the Whyalla steelworks (which releases ammonia), and fish farms (from uneaten food and fish waste), can add too many nutrients. This can lead to too much algae growth, which can harm the cuttlefish and other sea life. There were concerns that when fish farming increased, cuttlefish numbers went down. When fish farming stopped, the cuttlefish numbers recovered.

Oil pollution

In 1984, before the breeding grounds were discovered, a company called Santos built a plant nearby. There have been two major pollution events from this plant and port. In 1992, 300 tonnes of crude oil spilled into the sea. The effects of these spills on the cuttlefish are not known.

Salty water from desalination plants

Scientists and the local community have been worried about salty water (brine) released from desalination plants. These plants remove salt from seawater to make fresh water. In the 2000s, a company planned to build a large desalination plant very close to the breeding grounds. This plant would have released a lot of very salty water every day. Cuttlefish embryos (baby cuttlefish) don't develop well and can die if the water gets too salty. So, there was a lot of public opposition. The plan was approved in 2011 but was never built. Since then, two smaller desalination plants have started operating and release brine into the gulf.

Port plans

Because of the nearby ore deposits, several mining companies have wanted to build a large port next to Point Lowly. A new wharf for loading iron ore has been proposed. Local groups have formed to oppose new desalination plants and port developments near the cuttlefish breeding habitat. In 2021, a new port was approved for a different site. More shipping traffic in the Upper Spencer Gulf could also affect cuttlefish, as they are sensitive to loud, low-frequency sounds.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Sepia apama para niños

In Spanish: Sepia apama para niños