Ava Guaraní people facts for kids

The Ava Guaraní are a group of Indigenous people. They were once called Chiriguanos. They speak the Ava Guarani and Eastern Bolivian Guaraní languages.

These people were known for being strong fighters. They protected their lands in the Andes mountains of southeastern Bolivia. They fought against the Inca Empire, then the Spanish Empire, and later, independent Bolivia. The Chiriguanos were finally defeated in 1892.

After their defeat, the Chiriguanos almost disappeared from public view. But they started to become known again in the 1970s. Today, their descendants call themselves Guaranis. This connects them to millions of Guarani speakers in Paraguay, Argentina, and Brazil.

In 2001, about 81,011 Guaraní people lived in Bolivia. Most of them were Chiriguanos. A 2010 count found 18,000 Ava Guarani in Argentina. The Eastern Bolivian Guaraní language is spoken by many people in Bolivia, Argentina, and Paraguay.

Contents

Who Are the Ava Guaraní?

The name "Chirihuano" came from the Quechua language. It was used for traveling healers from Bolivia. Some people thought "chiri" meant "cold" in Quechua. So, the name was sometimes seen as meaning "people who die from freezing". In the late 1500s, the Spanish changed it to Chiriguanos.

The Chiriguanos called themselves "ava," which means "humans." Experts believe the Guarani people first lived in the central Amazon rainforest. They moved south a long time ago. It's not clear when they arrived in eastern Bolivia. The historical Chiriguanos were a mix of the Chané and the Guaraní. The Guaraní moved from Paraguay to Bolivia in the early 1500s. They joined with or took over the Chané people.

Some Ava Guaraní groups might have still been moving into the eastern Andes when the Spanish arrived in the 1530s. They might have been looking for Inca and Spanish riches. They also sought a mythical place called "Candire," a "land without evil" full of gold.

Their Way of Life

The Chiriguanos lived in the hills between the high Andes mountains and the flat Gran Chaco plains. They lived at heights between 1,000 and 2,000 meters (3,300 and 6,600 feet). The weather there is warm, and there is enough rain for farming. The area has steep hills and deep river valleys, making travel hard.

The Chiriguanos were not one big political group. Instead, they lived in villages. These villages formed loose groups led by a main chief, called a tubicha rubicha. The Spanish called these leaders capitán grande.

The Chiriguanos were warriors. They fought among themselves and against outsiders. They saw themselves as "men without masters." They thought they were better than other groups, whom they called "tapua" or "slaves." The Spanish often described them negatively. This made the Spanish feel it was okay to fight and enslave them.

The Chiriguanos got horses and guns from the Spanish. But they preferred to fight on foot with bow and arrows. The Spanish liked fighting on horseback with guns. The Chiriguanos were farmers, growing maize (corn) and other crops. They used to live in very large longhouses in villages. Later, probably for safety, they lived in smaller, spread-out settlements.

Until the 1800s, missionaries had little success in converting them to Christianity. In 1767, a Jesuit mission had only 268 Chiriguano converts. This was much fewer than the thousands converted in Paraguay.

Early Fights with Incas and Spanish

Spanish records from 1558 to 1623 say there were between 500 and 4,000 Chiriguano warriors. Even with European diseases, the Chiriguano population grew. This was partly because they included the Chané people. By the late 1700s, their population was over 100,000.

Large Chiriguano attacks against the Inca started in the 1520s. The Inca built forts, like Oroncota and El Fuerte de Samaipata, to stop them. The Spanish worried about Chiriguano raids in the 1540s. These raids threatened the Indigenous workers in the rich silver mines at Potosí. The Spanish also wanted to connect their settlements in the Andes and Paraguay.

In 1564, a Chiriguano leader named Vitapue destroyed two Spanish settlements. A big war between the Spanish and Chiriguanos began. In 1574, the Viceroy of Peru, Francisco de Toledo, led a large attack into Chiriguano land, but he failed. In 1584, the Spanish declared a "war of fire and blood" against them. In 1594, the Chiriguanos forced the Spanish to move their settlement of Santa Cruz. Some settlers even left the area and sailed down the Amazon River back to Spain.

In the early 1600s, the Spanish tried to settle the Andes foothills where the Chiriguanos lived. They set up three main defense points: Santa Cruz de la Sierra, Tomina, and Tarija. But by 1620, the Spanish stopped trying to expand much. For the next 100 years, there was mostly peace. The Spanish and their Indigenous allies lived somewhat peacefully with the Chiriguanos. However, there were still occasional raids from both sides.

The Jesuits tried to convert the Chiriguanos to Christianity in the 1630s. But they had little success.

18th Century Conflicts

A big uprising of the Chiriguanos started in 1727. This happened because the Spanish were settling lands near Tarija. Missionaries and ranchers wanted the rich pasture lands in the Andes foothills. The uprising began after missionaries punished some Chiriguano converts. One of the main leaders was Juan Bautista Aruma. However, the Chiriguanos were not fully united during this war.

In October 1727, the Chiriguanos, with help from the Toba and Mocoví, attacked. They had an army of 7,000 men. They destroyed Christian missions and Spanish ranches east of Tarija. They killed over 200 Spanish people and took many women and children captive. In March 1728, they attacked Monteagudo. They burned the church and took 80 Spanish prisoners.

The Spanish fought back in July 1728 with 1,200 Spanish soldiers and 200 Chiquitano archers. They destroyed many Chiriguano villages, killed over 200 people, and took more than 1,000 prisoners. The Spanish broke a truce and captured 62 Chiriguano leaders, including Aruma. They forced them to work in silver mines. Later Spanish attacks in 1729 and 1731 were less successful. In 1735, the Chiriguanos surrounded Santa Cruz. But 340 Chiquitano warriors from Jesuit missions broke the siege. That same year, the Chiriguanos destroyed two Jesuit missions near Tarija.

The Chiriguanos sometimes made their captives part of their society. Other captives on both sides were freed or traded. However, Spanish captives, especially women and children, often became slaves.

After this big uprising, more wars happened in the 1700s. These were in 1750 and from 1793 to 1799. These smaller wars were mostly about land and resources. The Chiriguanos were farmers who grew corn. The Spanish and Mestizo settlers were ranchers who raised cattle. The ranchers and their cattle destroyed Chiriguano farms. In return, the Chiriguanos killed cattle and sometimes ranchers.

19th Century Struggles

Until the 1860s, the Chiriguanos were very strong in the Andes borderlands. Spanish-speaking communities, called Creole or "karai," often paid tribute to local Chiriguano groups. Most of these people were of mixed Spanish and Indigenous heritage.

However, Chiriguano corn crops failed during a drought from 1839 to 1841. The Chiriguanos then raided more cattle herds. They ate the cattle and killed them to stop the ranchers from expanding. As the demand for meat grew in Bolivia, ranchers and soldiers put more pressure on the Chiriguanos. Also, the Chiriguano population seemed to shrink after the 1700s.

A key reason the Chiriguanos lost their independence was the return of Franciscan missions in 1845. After over 200 years of failure, Christian missions started to succeed. Many Chiriguanos went to the missions for safety. They sought protection from internal fights and conflicts with Creole ranchers, the Bolivian government, and other Indigenous groups. The missions and the Bolivian government used the labor of the mission Chiriguanos. They also recruited them as soldiers against independent Chiriguanos and other Indigenous people.

The number and independence of the Chiriguano also decreased after the 1850s. Many moved to Argentina to work on sugar plantations. By the 1860s, the Bolivian government became more aggressive. They gave large land grants to ranchers in Chiriguano territory. Mass killings of Chiriguanos became more common. Chiriguano fighters were often executed when captured. Women and children were sold into slavery.

The Chiriguanos made two last attempts to stay independent. These were the Huacaya War (1874-1877) and the rebellion of 1892. The 1892 rebellion started in January at the Santa Rosa de Cuevo mission. It was led by a 28-year-old man named Chapiaguasu. He called himself Apiaguaiki Tumpa (Eunuch of God). He said he was sent to save the Chiriguanos from Christianity and the missionaries.

Apiaguaiki led an army of 1,300 Chiriguanos in an attack on the mission on January 21. But they failed. The Creoles fought back on January 28. They had 50 soldiers, 140 Creole militia, and 1,500 friendly Indigenous people. In the Battle of Kuruyuki, the Creole army killed over 600 Chiriguanos. The Creoles lost only four soldiers, all Indigenous. After the battle, the Creole army killed Chiriguanos who surrendered. They also sold women and children into slavery. Most of the 2,000 Chiriguanos living at the Santa Rosa de Cuevo mission supported the Creole army.

Apiaguaiki was captured later. On March 29, 1892, Bolivian authorities executed him. His movement was similar to other Millenarian movements around the world. These include the Ghost Dance in the United States and the Boxer Rebellion in China.

20th and 21st Centuries

The influence of the Franciscan missions decreased during the 1900s. In 1930, a Chiriguano leader named Ubaldino Cundeye, his wife Octavia, and relatives moved to La Paz. They argued that Chiriguanos had rights as Bolivian citizens. Cundeye worked to help the Chiriguanos get their land back from the missions.

However, the Chaco War (1932-1935) caused many missions and Chiriguanos to lose their remaining land. Many Chiriguanos became migrant workers without land. Many went to Argentina. The missions were finally closed in 1949.

Communist revolutionary Ernesto "Che" Guevara tried to start a revolution among the Chiriguanos. But Bolivian soldiers captured and executed him on October 9, 1967. Guevara and his followers had learned Quechua to talk to Bolivian farmers. But the Chiriguanos spoke Guarani. In 2005, to attract tourists, the Guarani created the "Trail of Che Guevara." This trail is 300 kilometers (186 miles) long. It goes through the area where Guevara and his small army operated.

Today, the Eastern Bolivian or Ava Guaraní are increasingly called Ava Guaraní instead of Chiriguano. The name Chiriguano has negative origins. They are part of the Assembly of the Guaraní People. This group was founded in 1987. It represents Guarani people in several countries. The Guaraní are also part of the Confederation of Indigenous Peoples of Bolivia. Their goals are to get back some of their ancestral lands. They also work to improve their people's economy, education, and health.

A 2009 study found that 600 Guaraní families in Bolivia still live in conditions of "debt bondage and forced labor." These are forms of modern slavery.

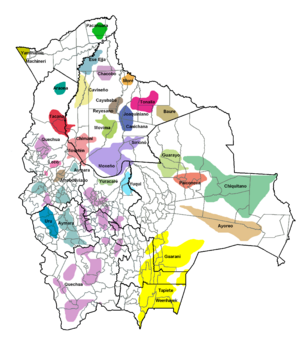

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Ava guaraníes para niños

In Spanish: Ava guaraníes para niños

| Jackie Robinson |

| Jack Johnson |

| Althea Gibson |

| Arthur Ashe |

| Muhammad Ali |