Axel Springer facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Axel Springer

|

|

|---|---|

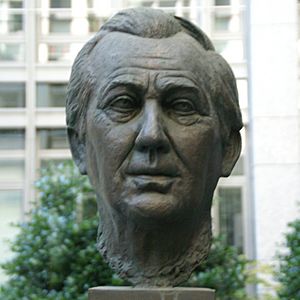

Springer in 1966

|

|

| Born |

Axel Cäsar Springer

2 May 1912 Altona, Hamburg, German Empire

|

| Died | 22 September 1985 (aged 73) |

| Occupation | Business, publishing |

| Spouse(s) | Martha Else Meyer (1933–1938) divorced Erna Frieda Berta Holm (1939–) divorced Rosemarie Alsen (1953–1961) divorced Helga Ludeweg (1962–) divorced Friede Springer (1978–1985) |

| Children | 3 |

| Relatives | Werner Lorenz (father-in-law) |

Axel Cäsar Springer (born May 2, 1912 – died September 22, 1985) was a famous German publisher. He founded what is now Axel Springer SE, one of the biggest media companies in Europe. By the early 1960s, his newspapers were very popular in West Germany. His newspaper, Bild, became the country's most widely read tabloid.

In the late 1960s, Springer faced challenges from student groups. His newspapers often wrote critically about student protests. This led to boycotts and attempts to stop his printing presses. In 1972, there was an attack on his company offices.

Later, in the 1970s, a reporter named Günter Wallraff wrote about some of the ways Springer's newspapers gathered information. This led to official warnings from the Press Council. Springer was sometimes called Germany's Rupert Murdoch, another big media owner. Despite the criticism, he managed to keep his strong position in the media world.

Springer also played a role in international discussions. He visited Moscow in 1958 and Jerusalem in 1966 and 1967. He believed his company's journalism should support Western countries and the North Atlantic alliance. He also strongly believed in "making peace between Jewish and German people" and supporting the country of Israel.

Contents

Early Life and First Steps in Publishing

Axel Caesar Springer was born on May 2, 1912, in Altona, a part of Hamburg, Germany. His father, Hinrich Springer, owned a small printing and publishing company. Axel learned the printing trade there.

Before World War II, his father's newspapers were sold by order of the government. Axel continued working for the company, which then printed books.

In 1933, Springer married Martha Else Meyer, who was Jewish. They divorced in 1938. At that time, new laws meant that editors married to Jewish people could not work. Springer later helped Martha and her mother, who survived a concentration camp.

Springer once said, "I cannot say I didn't know what was happening." He saw Nazi soldiers attacking Jewish people in Berlin in 1933. He never forgot what he saw.

Becoming a German Press Leader

From Radio Guides to Major Newspapers

After World War II, in 1946, Springer started his own publishing company, Axel Springer GmbH, in Hamburg. His first publication was Hörzu, a magazine with radio and later TV listings. Because he had not been a member of the Nazi party, he was able to get a license from the British authorities to run a newspaper.

His first daily newspaper was the Hamburger Abendblatt. He wanted to create a newspaper for "the everyday person." In 1952, he launched Bild for the national market.

Bild offered a mix of exciting stories, celebrity news, sports, and horoscopes. By the mid-1960s, it sold 4.5 million copies, making it the biggest newspaper in Western Europe and North America. The success of Bild allowed Springer to also publish Die Welt, a more serious national newspaper. In 1956, Springer also bought the famous Ullstein publishing house in Berlin. This included the Berliner Morgenpost newspaper.

Discussions with Moscow

Springer chose Hans Zehrer to be the chief editor for Die Welt. Zehrer had a history of nationalist views. At Die Welt, Springer allowed Zehrer to explore the idea of Germany becoming neutral, like Austria had in 1955.

In January 1958, Springer and Zehrer traveled to Moscow to meet with Nikita Khrushchev, the Soviet leader. Springer hoped for German reunification within five years. He also suggested a nuclear-free Central Europe.

The meeting did not go well. Khrushchev did not agree with Springer's ideas. This trip was very important for Springer. It convinced him that West Germany needed to stay allied with Western countries and NATO. After returning, he told his newspapers not to criticize Western allies. He believed Germany needed their support, especially for Berlin.

The Spiegel Affair

On October 26, 1962, the offices of Der Spiegel magazine in Hamburg were raided by police. The publisher and some editors were arrested. The defense minister accused them of treason for an article about NATO's plans.

Even though Der Spiegel was a critic of Springer, Springer offered his printing presses and office space. This allowed Der Spiegel to continue publishing. This event showed how important press freedom was.

Facing Criticism and Protests

Student Protests and the Anti-Springer Campaign

The Spiegel affair sparked student protests. Springer's newspapers often called these student groups "subversive," meaning they were trying to cause trouble.

In June 1967, many writers accused the Springer Press of "incitement" after a student protester was killed in West Berlin. Students had been protesting a visit by the Shah of Iran. Bild newspaper's response was very strong, comparing protesters to Nazi groups. Protesters then broke windows at Springer offices and tried to stop newspapers from being printed.

On April 11, 1968, Rudi Dutschke, a student leader, was shot by a right-wing extremist. Protesters blamed Bild newspaper, saying "Bild shot with him!" Serious unrest followed. Demonstrators tried to storm Springer's building in Berlin and set fire to Bild delivery vans. There were over a thousand arrests.

Helmut Schmidt, a Social Democrat leader, talked with Springer. Schmidt said that Springer's newspapers mixed "news and suggestive commentary." He suggested Springer change his company's structure. Springer and Schmidt later discussed the situation in Czechoslovakia.

On May 19, 1972, a group called the Red Army Fraction attacked Springer's Hamburg offices. Seventeen employees were injured. Many people, including writer Heinrich Böll, felt that the strong language in tabloid newspapers like Bild contributed to the violence.

Investigations into Springer's Influence

Critics worried that Springer's newspapers had too much power to shape public opinion. It was said that government ministers checked Die Welt every morning to see if Springer approved of them. The front page of Bild was also seen as very influential.

In 1968, a government group found that Springer controlled 40% of newspapers and 20% of magazines in West Germany. This was seen as a threat to press freedom. Springer sold some of his smaller newspapers to avoid official action.

A more serious issue for Springer came from journalist Günter Wallraff. In 1977, Wallraff secretly worked as an editor for Bild. He then wrote books exposing how Bild sometimes used unethical methods to get stories. Wallraff said that Bild often "broke into the private, even intimate sphere of the people it was reporting about."

The German Press Council gave Bild six warnings. After long legal battles, a court ruled in favor of Wallraff in 1981. The court said his writings showed "an aberration in journalism" that the public needed to know about.

Views on Germany and Ostpolitik

Springer believed that Germans were responsible for their country being divided after World War II. He felt that East Germans deserved the same chance at freedom and market economy as West Germans. Because of this, he refused to officially recognize the East German government. When the Berlin Wall was built in 1961, Springer built his 22-story headquarters right next to it. His writers often called East Germany the "Soviet Occupation Zone."

Springer strongly disagreed with Willy Brandt's "Ostpolitik" policy, which aimed to improve relations with East Germany and other Eastern Bloc countries. Springer believed this policy would "normalize" the East German regime.

East Germany's state television even made a 10-hour miniseries called Ich – Axel Cäsar Springer. It showed him as a puppet of secret Nazi groups after the war. East Germans were so impressed by Bild's power that they tried to sell their own tabloid, NEUE Bild Zeitung, to West Germans.

Springer's efforts to discredit the Social Democrats did not stop blue-collar workers from voting for Brandt. Springer, who always said that newspaper sales showed what the public wanted, eventually adjusted. He moved or parted ways with employees who were attacking Brandt too strongly. Later, Bild started referring to East Germany as the GDR (the German Democratic Republic), though often in quotation marks.

Brandt's Kneel in Warsaw

Springer's son, Axel Springer Jr., was a photographer and journalist. He is famous for his picture of Willy Brandt kneeling in front of a memorial in Warsaw on December 7, 1970.

Brandt was in Poland to sign a treaty that recognized the border between Germany and Poland. Springer himself wrote in Die Welt that he was outraged that a German government would agree to this.

A Friend of Israel

Springer's newspapers did not focus on the history of the Nazi era as much as some other publications. However, Bild did start reporting on trials of Nazi war criminals, including the Eichmann trial in Jerusalem in 1961. This was important because many West Germans at the time did not want to discuss the Nazi regime.

Many people believe that "no German played a more significant role in the effort to repair his country's burdened relationship with the Jews, and to ensure its support for their state, than Axel Springer." He dedicated his newspapers and his own money to this cause.

In 1966, Springer offered a large donation to The Israel Museum, Jerusalem. However, some Israelis protested accepting money from a German. It was eventually decided that a plaque would honor Springer's gift.

Springer returned to Jerusalem on June 10, 1967, to celebrate the capture of the Old City during the Six-Day War. He had told his newspapers to cover the war with a strong pro-Israel bias. He joked that he simply published Israeli newspapers in German. He wrote on the front page of Bild, "The Israelis have the right to live in peace."

Honors and Awards

Springer received special degrees from Bar-Ilan University in Israel (1974) and the Hebrew University of Jerusalem (1976). In 1977, he received the American Friendship Medal.

In 1978, he was given the first Leo Baeck Medal. In 1985, he received the gold medal from the Jewish service organization B'nai B'rith.

In 1981, Franz Josef Strauss gave Springer the Konrad Adenauer Freedom Prize. This was for his work in creating a free press system, his commitment to reuniting Germany, and his efforts to bring Germans and Jewish people together.

Death

Axel Springer died in West Berlin in 1985. His fifth and last wife, Friede Springer, inherited his company. She was 30 years younger than him and had been his son's nanny.

In 1971, Springer published a book of his speeches and essays called Von Berlin aus gesehen. Zeugnisse eines engagierten Deutschen.

See also

In Spanish: Axel Springer para niños

In Spanish: Axel Springer para niños

- William Denholm Barnetson

| Bayard Rustin |

| Jeannette Carter |

| Jeremiah A. Brown |