Rudi Dutschke facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Rudi Dutschke

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born |

Alfred Willi Rudolf Dutschke

7 March 1940 Schönefeld, Brandenburg, Germany

|

| Died | 24 December 1979 (aged 39) Århus, Denmark

|

| Alma mater | Freie Universität Berlin |

| Known for | Spokesperson of the German student movement |

| Spouse(s) |

Gretchen Klotz

(m. 1966) |

| Children | 3 |

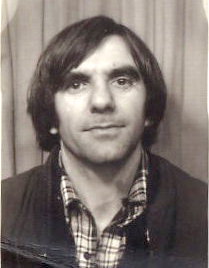

Alfred Willi Rudolf "Rudi" Dutschke (born March 7, 1940 – died December 24, 1979) was an important German student leader and political activist. He was a main figure in the German student movement in West Germany during the 1960s. He was known for speaking out against the government and for new ways of thinking about society.

Dutschke believed in a type of socialism that was different from what he saw in East Germany. He wanted people to have more direct control in their communities. He also supported independence movements in other parts of the world. Later, in the 1970s, he believed that Germany should be reunited and not be part of any major power blocs.

Sadly, Dutschke was badly injured in an attack in 1968. He died from these injuries in 1979. Before he passed away, he was chosen to be part of the new Green Party. This party wanted to be different from traditional political parties. It focused on environmental issues and social justice.

Contents

Early Life in East Germany

Rudi Dutschke was born in Schönefeld, near Luckenwalde, Germany. He was the fourth son in his family. He grew up and went to school in East Germany. In 1958, he finished high school. He then trained to be a salesman.

In 1956, he joined a youth group. He wanted to be a sports star. However, he also joined a church youth group. This group was not fully approved by the government. Dutschke said his faith was important to him. It helped him think about human possibilities.

In this church group, Dutschke became brave. He refused to join the army, which was required. He also encouraged others to do the same. He was inspired by the Hungarian Revolution of 1956 in 1956. This event made him think about a more democratic type of socialism.

Because he refused army service, he could not study sports journalism. So, in 1960, Dutschke started going to West Berlin for school. He got a new high school diploma there. He also worked for a newspaper called Bild Zeitung.

In August 1961, Dutschke became a refugee in West Berlin. This was just before the Berlin Wall was built. On August 14, he and his friends tried to tear down part of the new wall. They also threw leaflets over it. This was his first political action.

Student Activist in the 1960s

Starting at the Free University

Dutschke began studying at the Free University of Berlin in West Berlin. This university was started by students who left the Communist-controlled Humboldt University in East Berlin. The Free University was supposed to give students more say. But Dutschke felt that the university leaders were not truly democratic.

His studies made him question things even more. He learned about different ideas in sociology, philosophy, and history. These ideas helped him think about how society worked. He also learned about Karl Marx and other thinkers. Dutschke believed in individual freedom. He wanted to turn these ideas into real actions.

In 1963, Dutschke joined a group called Subversive Action. He helped edit their newspaper. He wrote about how people in other countries could start revolutions. In 1964, Dutschke's group protested a visit from the Prime Minister of Congo. Dutschke led protesters to a town hall. Tomatoes were thrown at the Prime Minister. Dutschke called this the start of their "cultural revolution."

Joining the SDS and Protests

In 1964, Dutschke's group joined the German Socialist Students Union (SDS). This group used to be part of the Social Democrats. But they were kicked out for being too far left. Dutschke was elected to the SDS council in West Berlin in 1965. He pushed for protests at the university and in the streets.

Dutschke believed that protests would show the government's true nature. He thought this would make people think about democracy. He had help from Michael Vester, an SDS leader. Vester had studied in the US. He brought ideas about "direct action" and "civil disobedience" from the American student movement.

In April 1965, Dutschke visited the Soviet Union. When he returned, his group focused on protesting the United States. They were very upset about the US actions in the Dominican Republic.

In 1965, Dutschke joined protests at the Free University. The university would not let a writer speak. This led to a sit-in protest in 1966. Students felt that the university leaders were too controlling. They saw this as part of a bigger problem with democracy.

Marriage and Family Life

On March 23, 1966, Dutschke married Gretchen Dutschke-Klotz. She was a theology student from Germany and America. Gretchen helped Rudi see that men in their group sometimes ignored women. She said, "When the women talked in meetings, the men laughed. I said to Rudi 'this is impossible' but I don't think he was aware of it up to that point."

The couple chose not to join a new shared living group in West Berlin. They felt it was not truly revolutionary. They had three children together. Their first son was named Hosea-Che. After he was born, Dutschke and Gretchen had to leave their home. People wrote threats and threw smoke bombs at their apartment.

Speaking Out for Change

On June 2, 1967, a student named Benno Ohnesorg was shot and killed by a policeman in West Berlin. This happened during a protest against the Shah of Iran. Many people were very angry. Dutschke called for taking over the conservative Springer Press. This company owned many newspapers, including Bild Zeitung. He said they were encouraging violence. The Bild Zeitung headline after the death was "Students threaten, We shoot back."

Protesters attacked Springer offices. This led to many arrests. The German Chancellor said it was a "revolutionary" situation. He asked people to be calm.

A philosopher named Jürgen Habermas criticized Dutschke. He said Dutschke was putting students at risk. Dutschke replied that he was proud of the criticism. He believed that revolutionaries should not just wait for change. He quoted Che Guevara: "Revolutionaries must not just wait for the objective conditions for a revolution. By creating a popular ‘armed focus’ they can create the objective conditions for a revolution by subjective initiative."

Dutschke later realized that the protests against Springer were not working. He decided to focus on the Vietnam War instead.

Protesting the Vietnam War

In 1966, Dutschke and the SDS held a big meeting about the Vietnam War. Many students and workers attended. They started "walking demonstrations" against the war in West Berlin. These were broken up by police. Dutschke and many others were arrested. Around this time, the media started calling Dutschke the "spokesman for the SDS."

In October 1967, Dutschke joined about 10,000 people protesting in West Berlin. At the same time, many people were protesting the Pentagon in Washington, D.C. Dutschke was hit on the head and could not speak.

In early 1968, the SDS planned a big international conference in West Berlin. They chose this city because it was between the two sides of the Cold War. The Technical University of Berlin agreed to host the event.

Many youth groups from different countries came. Dutschke spoke at the conference. The final statement said that the US was trying to control Western Europe. Dutschke wanted to lead a protest march to a US Army base. But after talking with others, he decided against it. He told students to spread out and hand out leaflets instead.

Three days later, a large counter-protest was held. Signs called Dutschke "The Enemy of the People." A young man was mistaken for Dutschke. He was chased and pushed by the crowd.

A "Long March Through Institutions"

Dutschke believed that revolution was a long process. He said people needed to change. This change would happen through a "long march through the institutions." This meant creating new institutions instead of trying to fix old ones.

He felt that the current political system did not represent people's true interests. He said there was a "total separation" between politicians and the people. He also thought that trade unions were not good for democracy from below.

Dutschke saw universities as "factories" that produced people who could not think critically. But he also saw them as "safety zones" where change could begin. In 1966, he called for a "permanent counter-university." This would help make universities more political.

Supporting the Prague Spring

Dutschke did not like the Grand Coalition government in West Germany. He felt it was not democratic enough. He joined calls for an "extra-parliamentary opposition" (APO). This group believed that the government was ignoring people's interests.

Dutschke also wanted to make sure student protests were not used by Soviet or East German propaganda. In March 1968, he visited Czechoslovakia. He supported the Prague Spring, a time of political reform there. He encouraged Czech students to combine socialism with civil rights.

The Idea of German Reunification

In an interview in 1967, Dutschke talked about German reunification. He believed that Germans had the right to decide if they wanted to live in one country again. He thought that a neutral, reunited Germany would help end the Cold War.

Dutschke was confused why the German left did not "think nationally." He believed that socialists in East and West Germany should work together. He said that East Germany was "part of Germany." He felt that a "socialist reunification of Germany" would weaken the power of the superpowers.

In 1967, Dutschke suggested that West Berlin should become a "council republic." He thought this could help reunite Germany. He believed it would inspire change in both German states.

Attack and Recovery

After visiting Prague, Dutschke planned to live in the US for a few years. He wanted to study liberation movements. He felt that the media had made him a leader, but he believed the student movement should not need one. On April 11, 1968, he was shot.

His attacker was Josef Bachmann, a construction worker. Bachmann had been in contact with a Neo-Nazi group. He was arrested after a shootout with police.

The Springer Press was again blamed for encouraging violence. Protesters tried to storm the Springer building in Berlin. They also set fire to delivery vans. In Munich, a protester and a policeman were killed after students attacked a Bild office. Over a thousand people were arrested.

Dutschke survived the attack. But he had serious injuries, including brain damage and memory loss. He also had epileptic seizures. The Dutschke family went to Italy to help him recover. When the press found them, they moved to England.

The University of Cambridge offered Dutschke a chance to finish his doctorate. He returned to Germany briefly in 1969 to talk about the future of the student movement. He said he could not play a big role because of his health. Back in England, the government denied him a student visa. So, he moved to Ireland.

In Ireland, Rudi and Gretchen Dutschke were visited by their lawyer. He tried to get them to support an underground group. But they refused. The Dutschkes thought about staying in Ireland. But they returned to the UK in 1969. In 1971, the UK government believed he was still too politically active. So, they made him leave. The University of Aarhus in Denmark offered him a job. The Dutschkes then moved to Denmark.

Later Years and Activism

Supporting Dissidents

Dutschke visited West Germany again in 1972. He talked with union members and politicians. He shared their idea of a neutral Germany. In July 1972, he visited East Berlin. He met with writers and activists who disagreed with the government. He also connected with other dissidents from Eastern Europe.

In 1973, he finally received his doctorate degree. He worked on a research project comparing labor markets in different countries.

Dutschke became more focused on civil rights. He spoke out against bans on people with radical political views from working in certain jobs. When a dissident named Rudolf Bahro was jailed in East Germany, Dutschke organized a meeting to support him.

In 1979, Dutschke, working for a newspaper, questioned the German Chancellor. He reminded the Chancellor that he was speaking to a free press. He wanted to ask why the Chancellor had not raised human rights issues with a Chinese leader.

"Patriotic Socialist"

In the 1970s, Dutschke was sometimes criticized. Some linked him to terrorism, others to nationalism. He kept talking about German reunification.

In 1974, Dutschke wrote that fighting for national independence was becoming part of the socialist struggle. He believed that the division of Germany by the "great powers" had failed. He said it was leading to more military build-up.

In 1976, Dutschke said that other countries' left-wing groups had a national identity. He felt that Germany needed to overcome its "loss of identity" after World War II. He believed that the "class struggle is international, but its form is national." Many on the West German left did not understand his "national thinking."

Joining the Green Movement

From 1976, Dutschke was part of the "Socialist Bureau." He supported a new "eco-socialist" movement. This movement would include anti-nuclear, anti-war, and environmental activists. But it would not include communists. He joined protests against a nuclear power plant in Germany.

From 1978, he campaigned for a green political group. In June 1979, he made joint appearances with artist Joseph Beuys. His appearance in Bremen helped the Green List win enough votes to enter parliament.

The Bremen Greens chose Dutschke as a delegate for the founding meeting of a federal Green Party. The Greens promised to be an "anti-party party." They wanted to stay a grass-roots movement.

In his last big speech, Dutschke again talked about the "German Question." He supported the right of nations to decide their own future. He also supported resistance against military alliances. This idea was different from the Greens' main view of nonviolence.

Death and Tributes

Rudi Dutschke continued to have health problems from the attack in 1968. On December 24, 1979, he had an epileptic seizure and died at age 39. He was survived by his wife, Gretchen Dutschke-Klotz, and their two children, Hosea Che and Polly Nicole. Their third child, Rudi-Marek, was born after his death.

Thousands of people attended Dutschke's funeral. It was seen as a farewell to the hopes of the 1960s for social change. A church leader praised Dutschke. He said Dutschke "fought passionately... for a more humane world." He also said Dutschke sought "a unity of socialism and Christianity." The Social Democrats in West Berlin said Dutschke's death was "the terrible price he had to pay."

In 2018, it was revealed that Rudolf Augstein, a newspaper publisher, helped Dutschke financially. He paid Dutschke money each year so he could work on his studies. They also wrote letters to each other about the student protests.

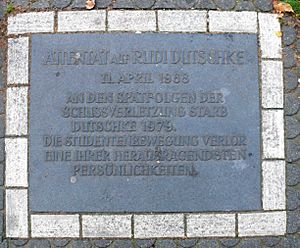

Memorials

There is a special stone in the pavement in Berlin where Dutschke was shot. It says that he died in 1979 from his injuries. It also says that the student movement lost one of its most important people.

In Berlin, there is a street named Rudi-Dutschke-Straße. This street was renamed in 2008 after many years of debate. It is near the Axel Springer high-rise building. The newspaper taz suggested the renaming. Some people disagreed. They said Dutschke was a controversial figure.

Legacy

In her 2018 book, Gretchen Dutschke-Klotz said her husband helped bring about an anti-authoritarian revolution in Germany. She believes this helped protect Germany from extreme right-wing groups. She feels that Germany has "held out pretty well so far against the extreme right-wing, and that has to do with the democratization process and culture revolution which the 68ers [Rudi Dutschke among them] carried out."

Others have different opinions. Some of Dutschke's ideas about Germany have been used by right-wing extremists. For example, a neo-Nazi group claimed that Dutschke would be one of them today. They pointed to some of his former friends who later became right-wing extremists.

However, many people who knew Dutschke disagree. They say he did not support such ideas. Some, like Ralf Dahrendorf, thought Dutschke was a good person. But they felt his ideas were not always clear. Dahrendorf said, "I don't know anyone who would say: that was Dutschke's idea, we have to pursue it now."

Works

- .

- (1963–1979).

- .

See also

In Spanish: Rudi Dutschke para niños

In Spanish: Rudi Dutschke para niños

- Kommune 1

- Sozialistischer Deutscher Studentenbund

- Rudi Dutschke – German Wikipedia

| Roy Wilkins |

| John Lewis |

| Linda Carol Brown |