Baldassare Galuppi facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Baldassare Galuppi

|

|

|---|---|

Galuppi by a Venetian artist, bearing date 1751

|

|

| Born | 18 October 1706 Burano

|

| Died | 3 January 1785 (aged 78) |

| Occupation |

|

| Organization | St Mark's Basilica |

|

Works

|

List of operas |

Baldassare Galuppi (born October 18, 1706 – died January 3, 1785) was a famous Italian composer. He was born on the island of Burano in the Venetian Republic. Galuppi was part of a group of composers who created a new style of music called "galant music" in the 1700s.

He became very successful around the world. He worked in cities like Vienna, London, and Saint Petersburg. But his main home was always Venice, where he held many important music jobs.

At first, Galuppi wrote serious operas called opera seria. But from the 1740s, he started working with a writer named Carlo Goldoni. Together, they became famous for their funny operas, known as dramma giocoso. Later composers even called him "the father of comic opera." Some of his serious operas were also very popular.

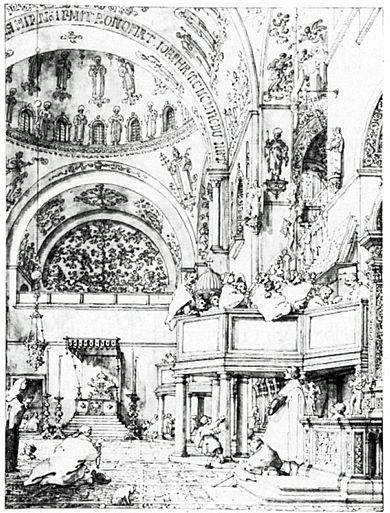

Throughout his life, Galuppi held important positions in Venice's churches and charities. His most important job was music director at St Mark's Basilica, the main church of the Doge. Because of these jobs, he wrote a lot of church music. He was also a skilled player and composer for keyboard instruments like the harpsichord.

After the 1700s, people outside Italy mostly forgot Galuppi's music. When Napoleon invaded Venice in 1797, many of Galuppi's original music papers were lost or destroyed. The English poet Robert Browning wrote a poem about him in 1855, called "A Toccata of Galuppi's." But this poem did not help his music stay popular.

For about 200 years after his death, Galuppi's works were rarely performed. However, in the late 1900s, his music started to be played and recorded much more often.

Contents

Who was Baldassare Galuppi?

His early life and music

Galuppi was born on the island of Burano in the Venetian Lagoon. From a young age, people called him "Il Buranello," which means "the little one from Burano." He even signed his music papers with this nickname. His father was a barber who also played the violin in theater orchestras. He probably taught Baldassare music first.

When Galuppi was 15, he wrote his first opera, Gli amici rivali. It was not very successful. Later, he studied music with Antonio Lotti, a main organist at St Mark's Basilica.

From 1726 to 1728, Galuppi worked as a harpsichord player in Florence. When he returned to Venice in 1728, he wrote another opera, Gl'odi delusi dal sangue. He wrote it with Giovanni Battista Pescetti, another student of Lotti. This opera was well-liked. After that, Galuppi started getting more requests to write operas and oratorios (large musical works for choir and orchestra).

In 1740, Galuppi became the music director at the Ospedale dei Mendicanti in Venice. This was a place that cared for the poor. His job was to teach music, conduct, and compose church music. In his first year, he wrote 31 pieces for the church. Even though he became famous for operas, he kept writing a lot of sacred music throughout his life.

Working in London and returning to Venice

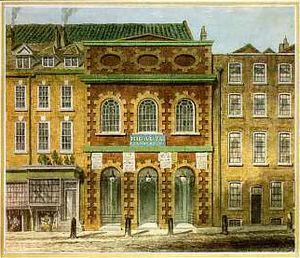

In 1741, Galuppi received an invitation to work in London, England. He asked for time off from his job in Venice, and they agreed.

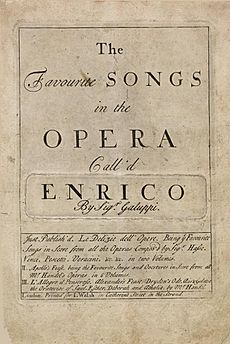

He stayed in England for 18 months. He oversaw productions for the Italian opera company at the King's Theatre. At least three of the 11 operas he directed were his own. The famous composer George Frideric Handel even attended one of these shows. Galuppi also became known as a great keyboard player and composer. An English music expert, Charles Burney, said Galuppi influenced English music more than any other Italian composer.

Galuppi returned to Venice in May 1743. He went back to his job at the Mendicanti and continued writing operas. The style of opera in Venice was changing from serious to funny. Galuppi helped this change. He adapted three comic operas for Venice in 1744. The next year, he wrote his own, La forza d'amore, which had some success.

He also kept writing serious operas, sometimes with the writer Metastasio. Metastasio believed the music should always serve the words. He complained about Galuppi, saying he was great for instruments and voices, but not for poets. Still, their joint works were popular and performed in other countries. Their operas Demetrio and Artaserse were huge hits in Vienna.

In May 1748, Galuppi got a new job as vice-maestro (assistant music director) at St Mark's Basilica. This job led him to compose many religious pieces. At first, the salary was not very high, and the choir was small. But his salary later increased, and he received a free house. This important position also gave him the freedom to write for other places, like opera houses in Venice, Vienna, London, and Berlin. By the time he died, Galuppi was one of the highest-paid composers of his time.

Galuppi was lucky when he started writing comic operas again in 1749. He worked with Carlo Goldoni, a famous playwright. Goldoni was happy for his words to support the music. Their first opera together was Arcadia in Brenta. They wrote four more works within a year. These operas were incredibly popular in Venice and other countries. To keep up with the demand, Galuppi had to leave his job at the Mendicanti in 1751. By the mid-1750s, he was "the most popular opera composer anywhere."

For the next ten years, Galuppi stayed in Venice. He occasionally traveled for new commissions and premieres. His operas, both serious and comic, were wanted all over Europe.

In April 1762, Galuppi became the main music director of St Mark's, the top music job in Venice. In July, he also became the choir master at the Ospedale degli Incurabili, another charity hospital. At St Mark's, he worked to improve the choir. He convinced the church leaders to pay singers better, which helped him attract talented performers.

Working for the Empress in Russia

In early 1764, Catherine the Great, the Empress of Russia, wanted Galuppi to come to Saint Petersburg. She wanted him to be her court composer and conductor. It took a long time for Russia and Venice to agree. Finally, Venice allowed Galuppi to go for three years. His contract said he would "compose and produce operas, ballets, and cantatas" for the court. He would earn a good salary and get a house and a carriage.

Galuppi was not sure about going, but Venetian officials promised he would keep his job and salary at St Mark's. He just had to send a Gloria and a Credo for the Basilica's Christmas mass each year.

In June 1764, Galuppi officially left Venice. He left his job at the Incurabili and made sure his wife and daughters were cared for. His son traveled with him. On his way to Russia, he visited C.P.E. Bach in Berlin. He also met Giacomo Casanova by chance. He arrived in Saint Petersburg on September 22, 1765.

For the Empress's court, Galuppi wrote new operas and church music. He also updated many old ones. He wrote one opera there, Ifigenia in Tauride (1768), and two cantatas. Besides his main work, Galuppi gave weekly harpsichord concerts. He sometimes conducted orchestral concerts too. He worked hard to improve the court orchestra. He was very impressed by the court choir, saying he had "never heard such a magnificent choir in Italy."

Galuppi was proud of his important jobs. The title page of his 1766 Christmas mass for St Mark's called him: "First Master and Director of all the Music for Her Imperial Majesty the Empress of all the Russias... and First Master of the Ducal Chapel of St. Mark's in Venice." In 1768, as planned, he returned to Venice. On his way back, he visited Johann Adolph Hasse in Vienna.

His later years

When he returned to Venice, Galuppi went back to his duties at St Mark's. He also got his job back at the Incurabili, staying there until 1776. After that, money problems forced all the charity hospitals to cut back on music. In his later years, he wrote more church music than opera. He continued to produce a lot of high-quality music.

Charles Burney visited him in Venice in 1771. Burney wrote that Galuppi's talent seemed to get better with age. He was nearly 70, but his latest operas and church music were full of more spirit and taste than ever before.

Galuppi told Burney his idea of good music: vaghezza, chiarezza, e buona modulazione (beauty, clearness, and good modulation). Burney also noted Galuppi's huge workload. Besides his jobs at St Mark's and the Incurabili, he was also an organist for a rich family and another church.

Galuppi's last opera was La serva per amore, first performed in October 1773. In May 1782, he conducted concerts for a visit by Pope Pius VI to Venice. He kept composing, even though his health was getting worse. His last known complete work was the 1784 Christmas mass for St Mark's.

After being sick for two months, Galuppi died on January 3, 1785. He was buried in the church of San Vitale. People greatly mourned him. Musicians paid for a special mass to honor him, and actors from the Teatro San Benedetto sang.

Galuppi's Music

Operas

Galuppi wrote 109 operas, making him one of the most productive opera composers of his time. Like many composers then, he often reused his own music. Sometimes he just moved it to a new piece, and other times he changed it a lot.

Musicians who came after him called him "the father of comic opera." Music experts say that Galuppi and Goldoni's operas truly started a new era for musical theater. They made the music a key part of the story, not just something pretty added on. Galuppi could show the characters' feelings and situations well through his music.

Galuppi and Goldoni also created the "large-scale buffo finale" to end acts in comic operas. Before them, acts usually ended with short choruses. But Galuppi's long and detailed finales set the pattern for later composers like Joseph Haydn and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart.

The music in Galuppi's comic operas often has words sung clearly, without long, drawn-out notes. This helped people understand the story. In his serious operas, he used the traditional da capo aria (a type of song with a repeated section). But he used it less often in his comic works. In serious operas, singers would sometimes add songs by other composers.

Sacred (Church) Music

Galuppi wrote at least 284 known sacred works. These include 52 masses, 73 psalm settings, 8 motets, and many other pieces for church. Many of his original music papers are kept in Dresden, Germany, and other cities around the world. It is hard to make a complete list of his church music because some papers are lost, and some works were wrongly said to be his.

In his religious music, Galuppi mixed old and new styles. It was common to use the stile antico (old style) in new church music. This style had smooth singing lines, like the music of Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina, and a lot of counterpoint (different melodies played at the same time). Galuppi used the old style carefully. When he wrote complex music for the choir, he balanced it with a bright, modern style for the orchestra.

His masses and psalm settings for St Mark's used all the musical tools available in the mid-1700s. The choir was supported by an orchestra with strings, flutes, oboes, bassoons, horns, trumpets, and organ. In his choir writing, Galuppi usually had the words sung clearly. He saved the more difficult, long singing passages for soloists.

Galuppi's church music written in Saint Petersburg influenced Russian church music for a long time. His 15 a cappella (unaccompanied choir) works with Russian words for the Orthodox church were very important. Their Italian style, with light counterpoint and Russian melodies, was continued by other composers.

Some works that were thought to be by Galuppi were later found to be by Vivaldi. Vivaldi's music, from an earlier time, was not popular after he died. So, some people put Galuppi's name on Vivaldi's music to make it more appealing.

Instrumental Music

Galuppi was highly praised for his keyboard music. Few of his sonatas were published when he was alive, but many still exist as handwritten papers. Some of his sonatas have one movement, like those by Domenico Scarlatti. Others have three movements, a form later used by Joseph Haydn and Ludwig van Beethoven.

Galuppi's skill as a keyboard player is well-known. People in Saint Petersburg said that his keyboard playing was "special" and "fiery." He earned praise from the entire court. It is not surprising that some of his keyboard works were printed during his lifetime.

Galuppi's seven experimental Concerti a quattro are very creative chamber music pieces. They were an early sign of the classical string quartet developing. Each concerto has three movements for two violins, viola, and cello. They combine the counterpoint of church sonatas with bold, changing harmonies.

Other instrumental pieces by Galuppi include sinfonias (symphonies), overtures, trios, string quartets, and concertos for solo instruments with strings.

Galuppi's Legacy

Robert Browning's poem A Toccata of Galuppi's talks about Galuppi and his music. We do not know if Browning was thinking of a specific piece. In Galuppi's time, the words "toccata" and "sonata" were used in similar ways. Many pieces have been suggested as the poem's inspiration. But it is impossible to say for sure which one it was. The poem inspired a modern musical piece by composer Dominick Argento in 1989.

After Browning's poem, a few of Galuppi's works were performed again. His music was played at memorials for the poet. But performances of Galuppi's music were still rare. La diavolessa was performed for the first time in 1952. Il filosofo di campagna was performed in 1959 and again in 1985.

Recordings

Since the late 1900s, more and more of Galuppi's works have been recorded. Some of his operas available on CD or DVD include Il caffè di campagna (2011), La clemenza di Tito (2010), La diavolessa (2004), and Il filosofo di campagna (1959 and 2001).

Several series of his keyboard sonatas have been recorded by different artists. Also, a two-CD set of keyboard sonatas played on the organ was released in 2016. Choral works on CD include the 1766 Messa per San Marco (2007) and various motets (2001).

Images for kids

-

Galuppi's best-known librettists, Metastasio, top, and Carlo Goldoni

-

Musicians' gallery in St Mark's, by Canaletto

See also

In Spanish: Baldassare Galuppi para niños

In Spanish: Baldassare Galuppi para niños