Giacomo Casanova facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Giacomo Casanova

|

|

|---|---|

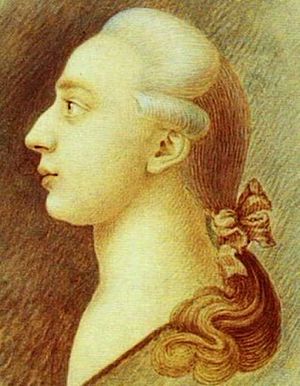

Drawing by his brother Francesco

|

|

| Born | 2 April 1725 Venice, Republic of Venice (now Italy)

|

| Died | 4 June 1798 (aged 73) Dux, Bohemia, Holy Roman Empire (now Duchcov, Czech Republic)

|

| Parent(s) |

|

Giacomo Girolamo Casanova (born April 2, 1725 – died June 4, 1798) was an Italian adventurer and writer. He was born in the Republic of Venice. His autobiography, Histoire de ma vie (Story of My Life), gives a lot of interesting information about how people lived in Europe during the 1700s.

Casanova often used different names, like baron or count of Farussi. He also used Chevalier de Seingalt. He signed his books as "Jacques Casanova de Seingalt" after he started writing in French. This was after he was sent away from Venice for the second time.

He said he met many important people. These included European kings and queens, popes, and cardinals. He also met famous artists and thinkers like Voltaire, Goethe, and Mozart. Casanova spent his last years working as a librarian at the Dux Chateau in Bohemia. This is where he wrote his life story.

Contents

Giacomo Casanova's Life Story

Early Life in Venice

Giacomo Girolamo Casanova was born in Venice in 1725. His mother, Zanetta Farussi, was an actress. His father, Gaetano Casanova, was an actor and dancer. Giacomo was the oldest of six children. His siblings were Francesco Giuseppe, Giovanni Battista, Faustina Maddalena, Maria Maddalena Antonia Stella, and Gaetano Alvise.

When Casanova was born, Venice was a lively city. It was a popular place for travelers. Many young men on the Grand Tour visited Venice. The famous Carnival and places to play games were big attractions. This was the world Casanova grew up in.

His grandmother, Marzia Baldissera, took care of him. His mother often traveled for her theater work. Casanova's father died when Giacomo was eight years old. As a child, Casanova had many nosebleeds. His grandmother even took him to an old woman who practiced folk magic. Casanova was very interested in the old woman's chants.

When he was nine, Casanova was sent to a boarding house in Padua. This was perhaps to help with his nosebleeds. He felt his parents neglected him. The boarding house was not good. So, he asked to live with his teacher, Abbé Gozzi. Gozzi taught him school subjects and how to play the violin. Casanova lived with the Gozzi family for most of his teenage years.

Casanova was a quick learner and loved to know new things. He started at the University of Padua when he was 12. He graduated at 17 in 1742 with a law degree. He also studied philosophy, chemistry, and math. He was very interested in medicine. While at university, Casanova started playing games for money. He quickly got into debt. This caused his grandmother to call him back to Venice. But the habit of playing games for money stayed with him.

Back in Venice, Casanova began a career in church law. He became an abbé after getting minor orders from the Patriarch of Venice. He continued his university studies in Padua. He was a tall, dark-haired young man. He powdered and curled his long hair. He soon became friends with Senator Alvise Gasparo Malipiero, a 76-year-old man. Malipiero lived near Casanova's home in Venice. The senator taught Casanova about good food, wine, and how to act in polite society.

Early Adventures and Travels

Casanova's short church career had some problems. After his grandmother died, he went to a seminary for a short time. But he soon ended up in prison because of his debts. His mother tried to get him a job with Bishop Bernardo de Bernardis. Casanova did not like the conditions there and left quickly. Instead, he found work as a writer for Cardinal Acquaviva in Rome. He even met Pope Benedict XIV. Casanova bravely asked the Pope for permission to read "forbidden books." He also wrote love letters for another cardinal. When a problem happened with two young lovers, Casanova was blamed. Cardinal Acquaviva let him go, ending his church career.

Casanova then bought a position as a military officer for the Republic of Venice.

He joined a Venetian army group in Corfu. He also made a short trip to Constantinople. He found military life boring and his progress too slow. He lost most of his pay playing a card game called faro. Casanova soon left the military and went back to Venice.

At 21, he tried to become a professional gambler. But he lost all his money. So, he went to his old friend Alvise Grimani for a job. Casanova became a violinist at the San Samuele theater. He did not like this job. He and his fellow musicians often played tricks on people at night.

Good luck came his way when he saved the life of a Venetian nobleman, Senator Bragadin. The senator had a stroke while riding in a gondola with Casanova. Doctors tried to help the senator, but Casanova thought their methods were making him worse. Casanova ordered the doctors to remove a strong ointment and wash the senator's chest with cool water. The senator got better. Because Casanova was young and seemed to know a lot about medicine, the senator and his friends thought Casanova had special knowledge. They invited Casanova to live with them. The senator became his helper for life.

For the next three years, Casanova lived like a nobleman. He dressed very well and spent his time playing games and meeting people. His helper was very understanding. But he warned Casanova that he would face problems one day. Casanova did not listen. Soon after, he had to leave Venice because of more problems.

He went to Parma. There, he had a three-month relationship with a Frenchwoman he called "Henriette." He said she was the deepest love he ever felt. She was beautiful, smart, and cultured. Casanova said, "They who believe that a woman is incapable of making a man equally happy all the twenty-four hours of the day have never known an Henriette."

Grand Tour and Imprisonment

Sad, Casanova went back to Venice. After winning some money playing games, he felt better. He then went on a long journey, called a Grand Tour. He arrived in Paris in 1750. In Lyon, he joined Freemasonry. This group interested him because of its secret rituals. It also helped him meet important and smart people. Casanova also liked Rosicrucianism.

He stayed in Paris for two years. He learned French, went to the theater, and met famous people.

In 1752, Casanova and his brother Francesco moved to Dresden. Their mother and sister Maria Maddalena lived there. Casanova's play, La Moluccheide, was performed at the Royal Theatre. His mother often played the main roles there. He then visited Prague and Vienna. He finally returned to Venice in 1753. In Venice, Casanova's record with the police grew longer. It listed fights and public problems. A spy was hired to learn about Casanova's secret group activities and to check his library for forbidden books. Senator Bragadin, his old helper, told him to leave Venice right away.

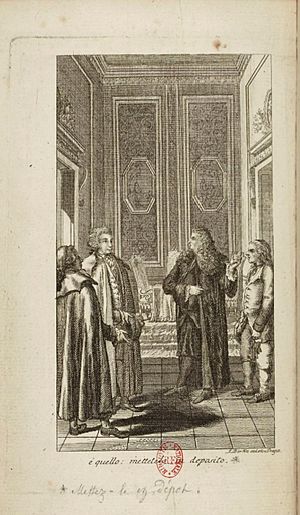

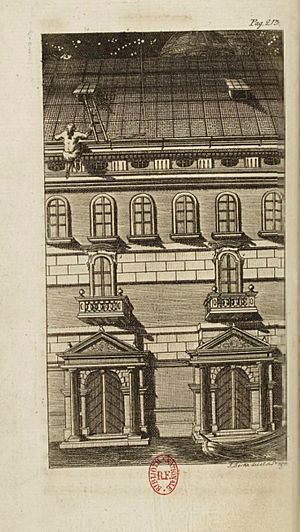

On July 26, 1755, when he was 30, Casanova was arrested. He was accused of disrespecting religion and public decency. He was put in "The Leads" prison. This prison was on the top floor of the Doge's palace. It was for important prisoners or certain types of offenders. On September 12, he was sentenced to five years in prison. He was not told why he was arrested or what his sentence was.

He was put in a small, dark room. He suffered from the heat and fleas. Later, he had cellmates. After five months, he was given warm bedding and money for books and better food. During walks in the prison attic, he found a piece of marble and an iron bar. He hid the bar in his armchair. When he was alone, he sharpened the bar into a spike. He started to dig through the wooden floor under his bed. He knew his cell was right above the Inquisitor's office. Just three days before he planned to escape, he was moved to a new cell. He was very upset because all his hard work was wasted.

Casanova then made another escape plan. He got help from Father Balbi, a prisoner in the next cell. Casanova's spike was passed to the priest inside a Bible. The priest made a hole in his ceiling. He climbed across and made a hole in Casanova's ceiling. Casanova then climbed through the ceiling. He left a note quoting a Bible verse: "I shall not die, but live, and declare the works of the Lord."

Casanova and Balbi climbed onto the roof of the Doge's Palace. It was foggy. They found a ladder and used a bedsheet rope to climb down into a room. They rested until morning. Then they changed clothes, broke a lock, and walked through the palace. They convinced a guard that they had been accidentally locked in. They left the palace at 6:00 AM and escaped by gondola. Casanova eventually reached Paris. He arrived on the same day (January 5, 1757) that someone tried to harm King Louis XV.

Thirty years later, in 1787, Casanova wrote Story of My Flight. It was very popular and printed in many languages. He told the story again in his memoirs.

Life in Paris and Other Travels

In Paris, Casanova decided he needed to be smart and careful. He wanted to meet powerful people and control himself. He found a new helper, de Bernis, who was France's Foreign Minister. De Bernis told Casanova to find a way to raise money for the state. Casanova became involved in the first state lottery. He was one of its best ticket sellers. This made him a lot of money quickly. He used his money to meet important people. He tricked many rich people with his knowledge of secret practices. He used his good memory to make it seem like he had special powers. Casanova believed that "deceiving a fool is an exploit worthy of an intelligent man."

Casanova claimed to be a Rosicrucian and an alchemist. These skills made him popular with important people like Madame de Pompadour, the Count of Saint-Germain, d'Alembert, and Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Many nobles were interested in alchemy, especially finding the "philosopher's stone." Casanova was sought after for his supposed knowledge and made a lot of money. He met his match in the Count of Saint-Germain, who claimed to be 300 years old and could create diamonds.

De Bernis sent Casanova on a spying mission to Dunkirk. Casanova was paid well for his work. He later wrote about how the French government spent too much money. He thought this would lead to problems and a revolution.

When the Seven Years' War began, Casanova was asked to help raise money for the government again. He was sent to Amsterdam to sell state bonds. Amsterdam was the financial center of Europe. He sold the bonds well. The next year, he was rich enough to start a silk factory. The French government even offered him a title and a pension if he became a French citizen. But he said no, perhaps because he loved to travel. Casanova had reached his highest point of wealth, but he could not keep it. He managed his business poorly and borrowed a lot of money trying to save it.

He was put in prison again for his debts, this time at For-l'Évêque. But he was freed four days later because the Marquise d'Urfé insisted. Sadly, his helper de Bernis was dismissed by King Louis XV at that time. Casanova's enemies then caused him more trouble. He sold his remaining things and took another mission to Holland to get away from his problems.

On the Run and Return to Venice

This time, his mission failed. He fled to Cologne, then Stuttgart in 1760. He lost the rest of his money there. He was arrested again for debts but escaped to Switzerland. Casanova visited the monastery of Einsiedeln and thought about becoming a monk. But he quickly changed his mind. He then visited Albrecht von Haller and Voltaire. He traveled to Marseille, Genoa, Florence, Rome, Naples, Modena, and Turin.

In 1760, Casanova started calling himself the Chevalier de Seingalt. He used this name for the rest of his life. Sometimes, he also called himself Count de Farussi. When Pope Clement XIII gave Casanova a special honor, he wore an impressive cross and ribbon.

Back in Paris, he tried one of his most unusual plans. He tried to convince the Marquise d'Urfé that he could turn her into a young man using secret methods. This plan did not make Casanova as much money as he hoped. The Marquise d'Urfé finally stopped believing him.

Casanova traveled to England in 1763. He hoped to sell his idea of a state lottery to English officials. He wrote that the English believed they were better than everyone else. He met King George III, using many valuable items he had taken from the Marquise d'Urfé. While working on these plans, he also spent a lot of time with women, as was his custom. He left England poor and sick.

He went to the Austrian Netherlands, got better, and then traveled all over Europe for the next three years. He covered about 4,500 miles by coach. He went as far as Moscow and Saint Petersburg. His main goal was to sell his lottery idea to other governments. But he did not succeed. A meeting with Frederick the Great did not help. In Russia, he met Catherine the Great, but she also said no to the lottery.

In 1766, he was forced to leave Warsaw. This was after a pistol duel with Colonel Franciszek Ksawery Branicki over an Italian actress. Both men were hurt. Casanova's left hand was wounded, but it healed on its own. From Warsaw, he traveled to Breslau in Prussia, then to Dresden. He returned to Paris for several months in 1767. He played games for money, but was then forced to leave France by King Louis XV himself. This was mainly because of his trick involving the Marquise d'Urfé. Casanova was now known across Europe for his wild behavior. It was hard for him to find success. So, he went to Spain, where he was less known. He tried his usual approach: using his contacts, dining with nobles, and meeting the local ruler, Charles III. But nothing worked. He traveled across Spain with little success. In Barcelona, he avoided being killed and was put in jail for six weeks. His Spanish adventure failed, and he returned to France briefly, then to Italy.

In Rome, Casanova worked to get permission to return to Venice. While waiting, he started translating the Iliad and wrote a play. To please the Venetian authorities, Casanova did some secret reporting for them. After many months, he wrote a letter directly to the Inquisitors. Finally, he received permission to return to Venice in September 1774, after 18 years away.

At first, his return to Venice was friendly. He was a celebrity. Even the Inquisitors wanted to hear how he escaped from their prison. Only one of his old helpers, Dandolo, was still alive. Casanova was invited to live with him. He received a small amount of money from Dandolo. He hoped to live from his writings, but it was not enough. He became a reporter for Venice again, paid for each piece of work. He reported on religion, morals, and trade, mostly based on gossip. He was disappointed. No good financial opportunities came up.

At 49, years of wild living and thousands of miles of travel had taken a toll. Casanova's face showed scars and his cheeks were sunken. His easygoing manner was now more careful.

Venice had changed for him. Casanova had little money for gambling and few friends to share his impulsive ways. He heard about his mother's death. He also visited Bettina Gozzi on her deathbed, which was very sad for him. His Iliad was published, but it sold few copies and made little money. He had a public argument with Voltaire about religion. Casanova believed people needed to live in ignorance for peace.

In 1779, Casanova found Francesca, a seamstress. She became his live-in partner and housekeeper, and she loved him very much. Later that year, the Inquisitors paid him to investigate trade between the papal states and Venice. Other writing and theater projects failed because he did not have enough money. Casanova was forced to leave Venice again in 1783. This happened after he wrote a harsh satire making fun of Venetian nobles. In it, he said that Grimani was his true father.

Forced to travel again, Casanova arrived in Paris. In November 1783, he met Benjamin Franklin at a presentation about air travel by balloon. For a while, Casanova worked as a secretary for Sebastian Foscarini, the Venetian ambassador in Vienna. He also met Lorenzo Da Ponte, who wrote the words for Mozart's operas. Casanova may have given ideas to Da Ponte for Mozart's opera Don Giovanni.

Final Years in Bohemia

In 1785, after Foscarini died, Casanova looked for another job. A few months later, he became the librarian for Count Joseph Karl von Waldstein. The count was a chamberlain for the emperor. He lived in the Castle of Dux in Bohemia (now the Czech Republic). The count liked Casanova when they met a year earlier. The job gave Casanova security and good pay. But Casanova said his last years were boring and frustrating. However, it was a good time for him to write. His health got much worse. He found life among the local people less exciting. He could only visit Vienna and Dresden sometimes for a change. Casanova got along well with the count, but the count was much younger. The count often ignored him at meals and did not introduce him to important guests. Most other people at Dux Castle did not like Casanova. His only friends seemed to be his fox terriers. Casanova decided he must live to write his memoirs, which he did until he died.

He visited Prague, the capital city of Bohemia, many times. In October 1787, he met Lorenzo da Ponte, who wrote the words for Mozart's opera Don Giovanni. This was in Prague when the opera was first performed. He likely met Mozart too. Casanova may have been in Prague in 1791 for the crowning of Emperor Leopold II. This event included the first performance of Mozart's opera La clemenza di Tito. Casanova wrote some ideas for a Don Juan play in 1787. But none of his ideas were used in Mozart's Don Giovanni.

In 1797, news came that the Republic of Venice no longer existed. Napoleon Bonaparte had taken over Casanova's home city. It was too late for him to go home. Casanova died on June 4, 1798, at 73 years old. His last words are said to have been "I have lived as a philosopher and I die as a Christian." Casanova was buried in Dux (now Duchcov in the Czech Republic). But the exact place of his grave is not known today.

Casanova's Memoirs

Casanova's last years were lonely and boring. This helped him focus on writing his Histoire de ma vie. Without it, his memory might have been forgotten. He started thinking about writing his memoirs around 1780. He began seriously in 1789. He said it was "the only remedy to keep from going mad or dying of grief." The first version was finished by July 1792. He spent the next six years making changes. He wrote that he found "no pleasanter pastime than to converse with myself about my own affairs." His memoirs were still being written when he died. His story only reached the summer of 1774. In a letter from 1792, he thought about not publishing them. He thought his story was bad and he would make enemies by telling the truth. But he decided to go ahead. He used initials instead of real names and made some parts less strong. He wrote in French because "the French language is more widely known than mine."

He also told his readers that they "will not find all my adventures." He left out parts that would have made people look bad. He said, "Even so, there are those who will sometimes think me too indiscreet; I am sorry for it." The book ends suddenly with hints of more stories that were not written.

When first published, the memoirs were in twelve volumes. The full English translation is over 3,500 pages long. Sometimes his timeline is confusing or wrong. Some of his stories are exaggerated. But many details are confirmed by other writings from that time. He was good at writing conversations. He wrote a lot about all kinds of people in society. Casanova was mostly honest about his mistakes and reasons. He shared his successes and failures with good humor. He did not show much regret. He celebrated the senses, especially music, food, and women. He described his fights, escapes, plans, and feelings. He showed that he truly "lived."

Casanova's family kept the original manuscript of his memoirs. It was later sold to a publisher. The first short versions were published in German around 1822, then in French. During World War II, the manuscript survived bombings. The memoirs were copied many times over the years. They have been translated into about twenty languages. The full original French text was not published until 1960. In 2010, the National Library of France bought the manuscript. They have started to make digital copies of it.

Gambling and Games

Gambling was a common activity in the social circles Casanova was part of. In his memoirs, Casanova talks about many types of games from the 1700s. These included lotteries, faro, basset, piquet, biribi, primero, quinze, and whist. He wrote about how much nobles and church leaders loved these games. Cheating was sometimes more accepted than it is today. Most players were careful about cheaters. All kinds of tricks were common, and Casanova found them amusing.

Casanova played games for money throughout his adult life. He won and lost large amounts. He learned from professional players. He said he was "relaxed and smiling when I lost, and I won without covetousness." But when he was badly tricked, he could become angry. He sometimes even called for a duel. Casanova admitted he was not disciplined enough to be a professional gambler. He said he did not have enough control over himself when he won or lost. He also did not like being seen as a professional gambler. Even though Casanova sometimes used gambling smartly to make money or meet people, he could also be reckless. He said, "What made me gamble was avarice. I loved to spend, and my heart bled when I could not do it with money won at cards."

Casanova's Impact and Legacy

Casanova was seen by people of his time as a special person. He was very smart and curious. Today, he is known as one of the best writers about his era. He was a true adventurer. He traveled all over Europe looking for opportunities. He sought out the most important people of his time. He worked for powerful people. He was also interested in secret groups and new ideas. He was a religious Catholic and believed in prayer. He also believed in free will and reason.

He had many jobs and interests. He was a lawyer, a churchman, a military officer, a violinist, a clever trickster, a food lover, a dancer, a businessman, a diplomat, a spy, a politician, a medic, a mathematician, a philosopher, and a writer. He wrote over twenty works, including plays and essays. His novel Icosameron is an early example of science fiction.

Born to actors, he loved theater and living a dramatic life. But with all his talents, he often avoided steady work. He got into trouble when being careful would have been better. He mostly lived by his quick thinking, strong will, luck, charm, and money given to him or gained by tricks.

Prince Charles de Ligne, who knew Casanova well, thought he was the most interesting man he had ever met. He said, "there is nothing in the world of which he is not capable."

Casanova's Writings

- 1752 – Zoroastro: Tragedia tradotta dal Francese (a play). Dresden.

- 1753 – La Moluccheide, o Sia i gemelli rivali (a play). Dresden.

- 1769 – Confutazione della Storia del Governo Veneto d'Amelot de la Houssaie. Lugano.

- 1772 – Lana caprina: Epistola di un licantropo. Bologna.

- 1774 – Istoria delle turbolenze della Polonia (History of the Troubles in Poland). Gorizia.

- 1775–78 – Dell'Iliade di Omero tradotta in ottava rima (translation of the Iliad). Venice.

- 1779 – Scrutinio del libro Eloges de M. de Voltaire par différents auteurs. Venice.

- 1780 – Opuscoli miscellanei (various short works). Venice.

- 1780–81 – Le messager de Thalie. Venice.

- 1782 – Di aneddoti viniziani militari ed amorosi del secolo decimoquarto sotto i dogadi di Giovanni Gradenigo e di Giovanni Dolfin. Venice.

- 1783 – Né amori né donne, ovvero La stalla ripulita. Venice.

- 1786 – Soliloque d'un penseur. Prague.

- 1787 – Icosaméron, ou Histoire d'Édouard et d'Élisabeth qui passèrent quatre-vingts un ans chez les Mégamicres, habitants aborigènes du Protocosme dans l'intérieur de nôtre globe (an early science fiction novel). Prague.

- 1788 – Histoire de ma fuite des prisons de la République de Venise qu'on appelle les Plombs (Story of My Flight). Leipzig.

- 1790 – Solution du probléme deliaque. Dresden.

- 1790 – Corollaire à la duplication de l'hexaèdre. Dresden.

- 1790 – Démonstration géometrique de la duplication du cube. Dresden.

- 1797 – A Léonard Snetlage, docteur en droit de l'Université de Goettingue, Jacques Casanova, docteur en droit de l'Universitè de Padou. Dresden.

- 1822–29 – First edition of the Histoire de ma vie (Story of My Life), in a German translation. The first full edition of the original French manuscript was not published until 1960.

Images for kids

-

Portrait of Manon Balletti by Jean-Marc Nattier (1757)

See also

In Spanish: Giacomo Casanova para niños

In Spanish: Giacomo Casanova para niños

- Don Juan

- Lothario

| Aaron Henry |

| T. R. M. Howard |

| Jesse Jackson |