Battle of Coronel facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of Coronel |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the First World War | |||||||

Die Seeschlacht bei Coronel, Hans Bohrdt |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 2 armoured cruisers 3 light cruisers |

2 armoured cruisers 1 light cruiser 1 auxiliary cruiser |

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 3 wounded | 1,660 killed 2 armoured cruisers sunk 1 light cruiser damaged |

||||||

The Battle of Coronel was a naval battle during the First World War. It happened on November 1, 1914, off the coast of Chile. In this battle, the Imperial German Navy, led by Vice-Admiral Maximilian von Spee, defeated a British squadron. The British ships were commanded by Rear-Admiral Sir Christopher Cradock.

Neither admiral fully expected to meet the other's main fleet. However, when they did, Cradock felt he had to fight, even though his ships were weaker. Spee won easily, sinking two British ships. Only three German sailors were injured. But this victory used up nearly half of Spee's ammunition, which he could not replace.

The British were shocked by their losses. They quickly sent more powerful ships, including two modern battlecruisers. These new ships later found and destroyed most of Spee's squadron on December 8, 1914, at the Battle of the Falkland Islands.

Contents

Why the Battle Happened

When World War I began, the British and Australian navies captured German colonies in the Pacific. They were also looking for the German East Asia Squadron, led by Vice-Admiral Maximilian von Spee. This German squadron had left its base in China. The British Admiralty wanted to destroy Spee's ships because they could disrupt trade in the Pacific Ocean.

On October 4, 1914, the British learned that Spee planned to attack trading ships off the coast of South America. Rear-Admiral Sir Christopher Cradock was sent to patrol this area. His squadron included the armoured cruisers HMS Good Hope (his main ship) and HMS Monmouth. It also had the light cruiser HMS Glasgow and the armed merchant ship HMS Otranto.

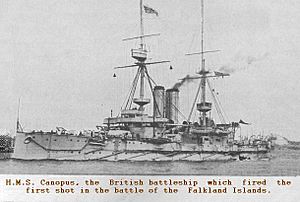

The British had planned to send a stronger ship, HMS Defence, to Cradock. But this ship was sent elsewhere temporarily. Instead, Cradock received an older battleship, HMS Canopus. This meant Cradock's squadron had older or less powerful ships. Many of their crew members were also less experienced.

Spee had a much stronger force. He had two powerful armoured cruisers, SMS Scharnhorst and Gneisenau. These ships had eight 8.2-inch guns each, giving them a big advantage in range and firepower. Spee also had three faster light cruisers: SMS Dresden, Leipzig, and Nürnberg.

The British Admiralty told Cradock to "be prepared to meet them." This order was not very clear. Cradock asked if he could split his fleet. He wanted one group for the east coast and one for the west coast of South America. The Admiralty agreed. The west coast squadron was joined by Canopus on October 18. However, Canopus was very slow. It could only go about 16 knots (18 mph). Cradock knew his faster ships would be too slow with Canopus. Without Canopus, his squadron was much weaker.

Cradock left the Falkland Islands on October 20. He still thought Defence would arrive soon. He had orders to attack German merchant ships and find Spee's squadron. As the British ships sailed around Cape Horn, they picked up radio signals from Leipzig. Cradock thought he might catch Leipzig alone. But Spee had already met up with Leipzig and ordered his ships to stay silent on the radio.

Communication Problems

On October 27, Admiral Jackie Fisher became the new head of the British Navy. He replaced Prince Louis of Battenberg. There were some misunderstandings between Cradock and the Admiralty.

Cradock sent a message on October 27. He said he planned to leave the slow Canopus behind. He would then search for Spee with his faster ships. He also said he still expected Defence to join him. The Admiralty had told him Defence was coming, but then it was sent to a different area.

The Admiralty expected Cradock to be careful. They wanted him to use Canopus for defense and just scout for the enemy. But Cradock believed he was expected to attack Spee with the ships he had. When Winston Churchill, who was in charge of the navy, received Cradock's message, he passed it on. He said he didn't fully understand what Cradock planned to do.

Cradock likely received Churchill's reply on November 1, just before the battle. He probably thought this message confirmed his plan was correct. Before leaving, Cradock had left a letter. In it, he said he did not want to be like another admiral, Ernest Troubridge. Troubridge was facing a court-martial for not fighting the enemy. Cradock's friends and colleagues believed he would never refuse a fight.

Getting Ready for Battle

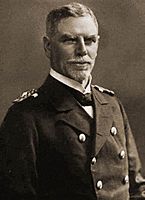

Maximilian von Spee

Sir Christopher Cradock

On October 22, Cradock told the Admiralty he would go around Cape Horn. He planned to leave Canopus behind to protect his supply ships. On October 28, Admiral Fisher ordered Cradock not to fight Spee without Canopus. He also ordered HMS Defence to join Cradock.

A week before the battle, Cradock sent Glasgow to Coronel to pick up messages. Spee learned that Glasgow was near Coronel. He sailed south from Valparaíso with all five of his warships to try and destroy her. Glasgow picked up German radio signals and told Cradock. Cradock then turned his fleet north to find the German ships.

Historians still wonder why Cradock chose to fight. The German ships were faster, had more firepower, and were more numerous. But Cradock had been told his force was "sufficient." Also, his friend, Admiral Troubridge, was in trouble for not fighting. Cradock's colleagues believed he was "constitutionally incapable of refusing action." On October 31, Cradock ordered his squadron to get ready to attack. Both sides likely expected to find only one or two enemy ships until they saw each other on November 1.

The Battle Begins

On October 31, Glasgow entered Coronel harbor to get messages. A German supply ship was also there and quickly radioed Spee about Glasgow. Glasgow heard German radio traffic, which suggested German warships were nearby. The German ships were all using the same radio call sign, which caused confusion. Spee decided to move his ships to Coronel to trap Glasgow. Cradock hurried north to catch Leipzig. Neither admiral knew the other's main fleet was so close.

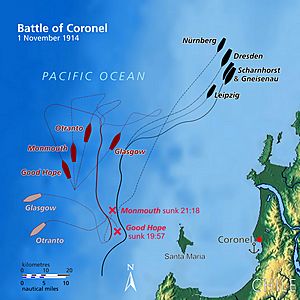

At 9:15 AM on November 1, Glasgow left port to meet Cradock. The sea was rough. At 1:05 PM, the British ships formed a line and sailed north, looking for Leipzig. At 4:17 PM, Leipzig and the other German ships saw smoke from the British line. Spee ordered his ships to go full speed. Scharnhorst, Gneisenau, and Leipzig approached the British at 20 knots (23 mph). The slower Dresden and Nürnberg were behind.

At 4:20 PM, Glasgow and Otranto saw smoke to the north and then three ships. The British ships turned around, and both fleets started moving south. A chase began that lasted 90 minutes. Cradock had a choice: he could run with his three faster cruisers, leaving Otranto behind, or stay and fight with Otranto, which was much slower.

The German ships slowed down to get into the best positions. They waited for the best visibility. This would be when the setting sun would outline the British ships against the sky.

At 5:10 PM, Cradock decided he had to fight. He brought his ships closer together. He tried to get closer to the German ships while the sun was still high. Spee, however, turned his faster ships away, keeping the distance between the fleets. They sailed roughly parallel, about 14,000 yards (12,800 meters) apart. At 6:18 PM, Cradock tried again to get closer. He steered directly towards the enemy. But the Germans again turned away, increasing the distance to 18,000 yards (16,500 meters).

At 6:50 PM, the sun set. Spee then closed the distance to 12,000 yards (11,000 meters) and began firing. The German ships had sixteen 8.2-inch guns. These guns had a similar range to the two 9.2-inch guns on Good Hope. One of Good Hope's large guns was hit within five minutes. Most of the British 6-inch guns were in casemates (armored compartments) along the sides of the ships. These guns would flood in the heavy seas if their doors were opened to fire.

The merchant cruiser Otranto had only eight 4.7-inch guns. It was also a much larger target. It quickly sailed west at full speed to escape.

Since the British 6-inch guns couldn't reach the German 8.2-inch guns, Cradock tried to get closer. By 7:30 PM, he was 6,000 yards (5,500 meters) away. But as he got closer, the German firing became even more accurate. Good Hope and Monmouth caught fire. They became easy targets for the German gunners in the darkness. The German ships, however, had disappeared into the night. Monmouth was the first to stop firing. Good Hope kept firing and trying to get closer to the German ships. It took more and more hits. By 7:50 PM, Good Hope also stopped firing. Then, its front section exploded, and it broke apart and sank. No one saw it sink, and there were no survivors.

Scharnhorst then focused its fire on Monmouth. Gneisenau joined Leipzig and Dresden, which had been fighting Glasgow. The German light cruisers had only 4.1-inch guns, which had done little damage to Glasgow. But now, Gneisenau's 8.2-inch guns joined in. John Luce, the captain of Glasgow, decided there was no point in staying and fighting. He noticed that every time his guns fired, the flash helped the Germans aim their next shots. So, he stopped firing. One part of his ship was flooded, but it could still go 24 knots (28 mph). He first went back to Monmouth, which was dark but still floating. There was nothing he could do for the ship, which was slowly sinking. Glasgow then turned south and left.

The German ships were unsure what happened to the two British armoured cruisers. They had disappeared into the dark after they stopped firing. A search began. Leipzig saw something burning but found only wreckage. Nürnberg, which was slower, arrived late to the battle. It saw Monmouth, listing and badly damaged but still moving. Nürnberg shined its searchlights on the British flag, inviting surrender. When Monmouth did not surrender, Nürnberg opened fire and finally sank the ship. Without clear information, Spee thought Good Hope had escaped. He called off the search at 10:15 PM. He then turned north, remembering reports that a British battleship might be nearby.

There were no survivors from either Good Hope or Monmouth. This meant 1,660 British officers and men died, including Admiral Cradock. Glasgow and Otranto both escaped. Glasgow was hit five times and had five wounded men. Scharnhorst was hit only twice, but neither shell exploded. One 6-inch shell hit above the armor and went into a storeroom. Another hit a funnel. Scharnhorst hit Good Hope at least 35 times. But it used up 422 of its 8.2-inch shells, leaving only 350. Gneisenau was hit four times. One shell almost flooded the officers' dining room. A shell from Glasgow hit its back gun turret, temporarily knocking it out. Three of Gneisenau's men were wounded. It used 244 shells and had 528 left.

What Happened Next

This battle was a big defeat for the British Navy. When the news reached the Admiralty, they quickly put together a new naval force. This force was led by Vice-Admiral Doveton Sturdee. It included two powerful battlecruisers, HMS Invincible and Inflexible. This new force found and destroyed Spee's squadron at the Battle of the Falkland Islands.

Glasgow, which escaped the battle, sailed south for three days. It passed through the Straits of Magellan. Canopus, warned by Glasgow's messages, turned around and headed back. On November 6, the two ships met and slowly went towards the Falklands. Canopus had problems twice during the trip. It was finally ordered to be beached in Stanley Harbour. There, it could act as a defensive gun battery.

Otranto sailed 200 nautical miles (230 miles) into the Pacific Ocean. Then it turned south and went around Cape Horn. On November 4, the Admiralty ordered the surviving ships to a meeting point. A new force was gathering there. Rear-Admiral Archibald Stoddart, with the armoured cruisers HMS Carnarvon and Cornwall, was to meet them. They would then wait for Defence to arrive. Sturdee was ordered to travel with the battlecruisers Invincible and Inflexible to command a new squadron. This squadron would be much stronger than Spee's.

Even though he won, Spee was not hopeful about his own chances of survival. He didn't think he had done much harm to the British navy. Winston Churchill later explained the defeat to the British Parliament. He said Cradock felt he couldn't fight the enemy if he stayed with the slow Canopus. So, he decided to attack with his faster ships alone. He believed that even if he was destroyed, he would damage the Germans enough for them to be destroyed later.

On November 3, Scharnhorst, Gneisenau, and Nürnberg entered Valparaiso harbor. The German people there welcomed them. But Spee refused to join the celebrations. When offered flowers, he said, "these will do nicely for my grave." He died with most of his men on December 8, 1914, at the Battle of the Falkland Islands.

Remembering the Battle

The Coronel Memorial Library at Royal Roads University in Canada is named after this battle. It honors the four Canadian midshipmen who died on HMS Good Hope. In 1989, a memorial was built in Coronel, Chile. It has two plaques showing HMS Good Hope and HMS Monmouth. A central plaque (in Spanish) says:

In memory of the 1,418 officers and sailors of the British military squadron and their Commander-in-Chief, Rear Admiral Sir Christopher Cradock, Royal Navy, who sacrificed their lives in the Naval Battle of Coronel, on 1 November 1914. The sea is their only grave.

—21st May Square plaque

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Batalla de Coronel para niños

In Spanish: Batalla de Coronel para niños

| Percy Lavon Julian |

| Katherine Johnson |

| George Washington Carver |

| Annie Easley |