British nuclear tests at Maralinga facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Maralinga Atomic Test Site in South Australia |

|

|---|---|

| Near Maralinga in Australia | |

Map showing nuclear test sites in Australia

|

|

| Coordinates | 30°10′S 131°37′E / 30.167°S 131.617°E |

| Type | Nuclear test range |

| Site information | |

| Operator | United Kingdom |

| Status | Inactive |

| Site history | |

| In use | 1955–1963 |

| Test information | |

| Nuclear tests | 7 |

| Remediation | Completed in 2000 |

The Maralinga site in South Australia was a place where the United Kingdom (UK) carried out nuclear tests. It is part of the Woomera Prohibited Area, about 800 kilometres (500 miles) north-west of Adelaide. Between 1956 and 1963, the UK conducted seven major nuclear tests here.

These tests included two main series: Operation Buffalo in 1956 and Operation Antler in 1957. The power of these weapons ranged from 1 to 27 kilotons (the same as 1,000 to 27,000 tons of TNT).

Maralinga was also used for many smaller tests. These "minor trials" involved testing parts of nuclear weapons without causing a nuclear explosion. For example, "Kittens" tested how a nuclear reaction starts. "Rats" and "Tims" looked at how the core of a weapon was squeezed by explosives. "Vixens" studied what happened if atomic weapons caught fire or exploded accidentally. These smaller tests, around 550 of them, actually caused more long-term radioactive pollution than the big explosions.

After the tests, the site was left with radioactive waste. An early cleanup happened in 1967. Later, a big report in 1985 found that dangerous radiation still existed. It suggested another cleanup, which finished in 2000 and cost 108 million Australian dollars. There was also a payment of 13.5 million dollars in 1994 to the Maralinga Tjarutja people, who are the traditional owners of the land.

Contents

- Why Did Britain Test Nuclear Weapons in Australia?

- Choosing the Maralinga Site

- Protecting People: The Safety Committee

- Impact on Aboriginal People

- Operation Buffalo: The First Big Tests (1956)

- Operation Antler: New Tests (1957)

- Minor Trials: The Hidden Tests

- The End of Testing at Maralinga

- Maralinga's Lasting Impact

- Maralinga in the Media and Arts

- Images for kids

Why Did Britain Test Nuclear Weapons in Australia?

The Need for British Bombs

During World War II, Britain worked with the United States and Canada on nuclear weapons. After the war, the US stopped sharing its nuclear technology. Britain worried about losing its power and decided to develop its own nuclear weapons. This secret project was called "High Explosive Research."

Australia's Role and Support

In the 1950s, Britain and Australia had strong connections. Australia's Prime Minister, Robert Menzies, was very supportive of Britain. Australian and British soldiers fought together in wars like the Korean War. Australia hoped to work with Britain on nuclear energy and weapons.

Australia had lots of open space, which was perfect for testing. The Australian Minister for Supply, Howard Beale, said in 1955 that "England has the know how; we have the open spaces."

Early Tests in Australia

Britain tested its first nuclear weapon in 1952 in the Montebello Islands off Western Australia. Then, in 1953, the first tests on the Australian mainland happened at Emu Field in South Australia.

Choosing the Maralinga Site

Finding the Perfect Spot

The earlier test sites were not ideal for long-term use. The Montebello Islands were hard to reach, and Emu Field had water problems and dust storms. Britain wanted a permanent test site.

They needed a place that was:

- Far from people (a 160-kilometre or 100-mile empty zone).

- Connected by roads and railways to a port.

- Near an airport.

- Had good weather with little rain.

- Had winds that would carry fallout away safely.

- Was mostly flat.

- Very isolated for security.

After looking at different places, an area north of Ooldea was chosen. It was flat and dry, without the dust storms of Emu Field. In 1953, this site was named "Maralinga." This is an Aboriginal word meaning "thunder," though it came from a different Aboriginal language than the local one.

Setting Up the Site

Australia and Britain worked together to build the Maralinga test site. It covered about 52,000 square kilometres (20,000 square miles). The main test area was 260 square kilometres (100 square miles).

A railway station and a quarry were built at Watson. Roads were made, and a main camp called "The Village" was built. It had an airstrip, laboratories, workshops, shops, a hospital, and even a swimming pool. By 1959, The Village could house 750 people.

Australian soldiers helped build the test facilities. They put up towers, set up instruments, laid cables, and built bunkers. This work was difficult because the location was so remote.

Protecting People: The Safety Committee

To make sure the tests were safe, Australia set up the Atomic Weapons Tests Safety Committee (AWTSC) in 1955. This group of scientists checked if the tests would harm people. They also looked at the dangers of radioactive fallout from nuclear tests around the world.

Impact on Aboriginal People

Prime Minister Menzies said that "no conceivable injury to life, men or property could emerge from the tests." However, the Maralinga site was home to the Pitjantjatjara and Yankunytjatjara Aboriginal people. This land was very important to them spiritually.

A Native Patrol Officer, Walter MacDougall, was in charge of keeping Aboriginal people away from the test site. He tried different ways to do this, including closing missions where they got food. He also tried to scare them by saying the noise of the tests came from dangerous spirits.

Operation Buffalo: The First Big Tests (1956)

What Was Tested?

Operation Buffalo was the first and largest series of nuclear tests at Maralinga. It included four tests. One goal was to test a new, smaller bomb called "Red Beard." Another was to see what happened during a ground explosion, which was known to create more fallout.

About 1,350 people were involved, including scientists, military personnel, and observers from other countries.

Test 1: One Tree

The first test, "One Tree," was a Red Beard bomb placed on a tower. It was supposed to happen on September 12, 1956, but bad weather caused delays. This made politicians and journalists unhappy.

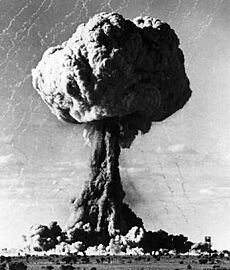

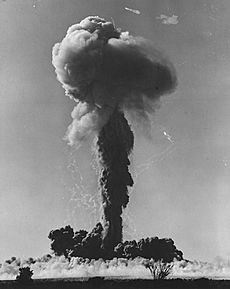

Finally, on September 27, the bomb was detonated. It had a yield of about 15 kilotons. The mushroom cloud rose very high and drifted eastward. Rain later caused some fallout to fall in Queensland and New South Wales.

Test 2: Marcoo

"Marcoo" was a ground test using an older "Blue Danube" bomb. It was placed in a concrete pit and detonated on October 4. It created a crater 49 metres (160 feet) wide and 12 metres (40 feet) deep. The yield was 1.5 kilotons.

Test 3: Kite

"Kite" was the only bomb dropped from an aircraft during Operation Buffalo. A Royal Air Force (RAF) bomber dropped a Blue Danube bomb on October 11. It detonated in the air, 150 metres (490 feet) above the ground. The yield was 3 kilotons. This was the first time a British nuclear weapon was dropped from a plane. Fallout from this test was very small.

Test 4: Breakaway

The last test, "Breakaway," was a boosted Red Beard bomb on a tower. It was detonated on October 22, with a yield of about 10 kilotons. The cloud reached 10,600 metres (35,000 feet) high.

Operation Antler: New Tests (1957)

Why More Tests?

Britain wanted to continue testing new, lighter nuclear weapons. The 1956 Suez Crisis made relations with the US difficult, so using US test sites was not an option.

Scientists also started using large balloons to lift bombs higher into the air. This was a new idea for Maralinga. Detonating bombs high up meant less radioactive dirt would be sucked into the explosion, making them "cleaner" tests.

Test 1: Tadje

The "Tadje" test happened on September 14, 1957. It was a tower test with a yield of about 1.5 kilotons. This test used tiny pieces of cobalt as a "tracer" to measure the yield. This led to rumors that Britain was making a "cobalt bomb." Some workers who handled these pieces were exposed to radiation.

Test 2: Biak

The "Biak" test was on September 25. It was also a tower test, with a yield of about 6 kilotons. The cloud rose much higher than expected.

Test 3: Taranaki

"Taranaki" was the balloon test, happening on October 9. Three large balloons were needed to lift the bomb. During a storm, some balloons broke free, which caused concern. The bomb detonated high in the air, with a yield of about 26.6 kilotons. Because it was high up, the fallout was limited.

Minor Trials: The Hidden Tests

Besides the big nuclear explosions, about 550 "minor trials" were conducted between 1953 and 1963. These were not nuclear explosions but experiments with nuclear weapon parts. They involved materials like plutonium, uranium, and beryllium. These trials were kept more secret, especially after 1958, to avoid public attention.

Kittens Series

"Kittens" tests helped develop the "neutron initiator," a part that starts a nuclear chain reaction. These tests spread materials like beryllium and polonium-210. Six Kitten tests were done at Maralinga in 1956, and many more followed until 1961.

Tim Series

"Tim" experiments measured how the core of a nuclear weapon was squeezed by explosives. These tests used real weapon parts but with non-fissile uranium. They took place from 1955 to 1963, spreading uranium and plutonium around the test sites.

Rat Series

"Rat" trials also studied shock waves, but they used a small, short-lived gamma ray source inside the weapon parts. These tests spread uranium-238 and other radioactive materials, but because these materials had short half-lives, they quickly decayed away.

Vixen Series

"Vixen" trials were about safety. They checked if a nuclear weapon would accidentally explode if it caught fire or crashed. These tests often involved blowing up nuclear warheads with explosives.

The "Vixen B" tests were particularly messy. They blew up plutonium-containing warheads, creating "jets of molten, burning plutonium." This caused the Taranaki site to become the most contaminated area at Maralinga. Plutonium is dangerous if it gets inside the body, especially if tiny particles are breathed in.

The End of Testing at Maralinga

Maralinga was meant to be a long-term test site, but public support for nuclear testing in Australia dropped. By 1957, most Australians were against it. This, along with a worldwide pause in nuclear testing, meant Operation Antler was the last major test series at Maralinga.

Britain also gained access to the US test site in Nevada. In 1963, the Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty banned atmospheric testing. Since Maralinga wasn't set up for underground tests, it became less useful.

In 1967, Britain officially ended its agreement to use Maralinga. Most of the land was returned to free access by 2014.

Maralinga's Lasting Impact

Cleanup Efforts

The first cleanup, called Operation Brumby, happened in 1967. Workers tried to mix the contaminated soil and buried radioactive fragments in concrete-capped pits.

However, a later report in 1985 found that dangerous radiation still existed. A bigger cleanup was done from 1996 to 2000, costing 108 million dollars. In the most contaminated areas, 350,000 cubic metres of soil and debris were removed and buried.

Most of the site is now safe for people to visit, but about 120 square kilometres (46 square miles) are still not safe for permanent living. Some experts say that Aboriginal people living a traditional lifestyle in this area could still receive unsafe levels of radiation.

Health Effects and Compensation

Some Australian servicemen were ordered to fly through mushroom clouds or walk into ground zero after explosions. A 1999 study found that many veterans died from cancers, often in their fifties.

The Australian government later paid compensation to some servicemen who developed specific types of cancer, like leukemia.

The forced movement of Aboriginal people from their lands and the contamination caused by the tests had a huge impact on their communities. In 1994, the Australian government paid 13.5 million dollars in compensation to the Maralinga Tjarutja people.

Maralinga in the Media and Arts

Media Coverage

At first, there was little reporting on the tests. But by the late 1970s, journalists started investigating. Whistle-blowers, like Avon Hudson, shared details about the inadequate cleanup and health risks.

Journalists like Brian Toohey and Ian Anderson wrote important articles about Maralinga. Alan Parkinson's 2007 book, Maralinga: Australia's Nuclear Waste Cover-up, claimed the cleanup was done cheaply and left hazards behind.

Art and Stories

The Maralinga story has been told in many ways through art, drama, and music.

- Art: Artists like Winnie Bamara, Betty Muffler, and Yhonnie Scarce have created powerful artworks about the tests and their impact on Indigenous people and the land.

- Drama: Films like Ground Zero (1987) and TV series like Operation Buffalo (2020) explore the events. The documentary Maralinga Tjarutja (2020) shares the story from the perspective of the Indigenous people.

- Books: Maralinga: The Anangu Story (2009) is an information book for young people about the history and culture of the region.

- Music: Bands like Midnight Oil and musicians like Paul Kelly have written songs about Maralinga and its effects.

Images for kids