Bermuda petrel facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Bermuda petrel |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Composite image | |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Genus: |

Pterodroma

|

| Species: |

cahow

|

|

|

The Bermuda petrel (Pterodroma cahow) is a type of gadfly petrel, a seabird known for its fast, acrobatic flight. In Bermuda, it's commonly called the cahow. This name comes from the strange, eerie sounds it makes. This nocturnal (active at night) seabird nests on the ground. It is the national bird of Bermuda and you can even see it on Bermudian money!

For about 300 years, people thought the cahow was completely gone. But in 1951, scientists made an amazing discovery: eighteen pairs of these birds were found nesting! This made the cahow a "Lazarus species". This means it's a species found alive after everyone thought it was extinct. This inspiring story has been featured in books and movies. A special program in Bermuda has helped protect the bird and increase its numbers. Scientists are still working to make more nesting places for them on Nonsuch Island.

Contents

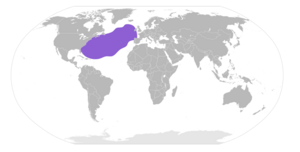

What do cahows eat?

Cahows usually eat small fish, squid, and tiny shrimp-like creatures. They mostly find their food in colder ocean waters. Studies done between 2009 and 2011 showed where they hunt. During the non-breeding season (July to October), they look for food in two main areas. One area is between Bermuda, Nova Scotia, and North Carolina. The other is north and northwest of the Azores archipelago (a group of islands).

Cahows have special glands in their tube-like nostrils. These glands help them drink seawater. They filter out the salt and then sneeze it out!

Cahow life cycle and reproduction

Cahows used to be very common all over the Bermuda islands. But their nesting areas have shrunk a lot. This happened because their homes were damaged and new animals were brought to the islands. Now, they only nest on four small islands in Castle Harbor, Bermuda. These islands are in the warm waters of the Gulf Stream, about 650 miles east of North Carolina.

The cahow is a slow breeder, meaning it doesn't have many chicks. However, it is an amazing flyer! It only comes to land to nest. Most of its adult life is spent flying over the open seas. They travel from the North Atlantic coasts of the United States and Canada to waters near western Europe. After spending 3 to 4 years at sea, male cahows return to the breeding islands to build nests.

Breeding season

The breeding season for cahows is from January to June. They nest in burrows, which are like underground tunnels. They choose burrows that are completely dark inside. Female cahows return after 4 to 6 years at sea to find a mate. Each female lays only one egg per season. About 40% to 50% of these eggs do not hatch.

Both parents take turns sitting on the egg to keep it warm. This is called incubation. It takes about 53 to 55 days for the egg to hatch. Chicks usually hatch between May and June. Cahows stay with the same mate for their whole lives. They also tend to return to the same nest every year.

Studying cahow nests

A high school science project used a live webcam to study cahow nests. This was the first time such a remote study was done for this species. The study watched how the parents took care of the egg. It found that both male and female parents shared the incubation duties equally.

The parents spent most of their time resting (56%), sleeping with their head tucked back (31%), cleaning their feathers (5%), and fixing the nest (3%). They were very attentive to the egg, leaving it alone only 1.5% of the time. The study also measured their breathing rates and head movements for the first time in a seabird. Both parents were in the nest together for only 11 out of 55 days of observation.

History of the Bermuda petrel

In the 1500s, Spanish sailors used Bermuda as a stop on their way to the Americas. Back then, cahows were everywhere and made loud, busy colonies. Sailors would catch up to 4,000 birds a night for food. They also brought hogs to the island for food. These hogs caused a lot of damage to the ground-nesting cahows. They dug up their burrows, ate eggs, chicks, and even adult birds. This messed up the birds' breeding cycle.

English settlement

In 1609, an English ship called the Sea Venture crashed on Bermuda. The people who survived ate many of the fattest petrels and collected their eggs. This was especially important in January when other food was scarce. Most survivors continued their journey, but three men stayed. More English settlers arrived in 1612, and Bermuda officially became part of Virginia.

When the English settled Bermuda, they brought new animals like rats, cats, and dogs. These animals, along with people hunting the birds for food, greatly reduced the cahow population. The remaining cahows also suffered because settlers burned plants and cut down forests. Even though one of the world's first conservation laws was made to protect them, the cahows were thought to be extinct by the 1620s. This law was called the governor's proclamation "against the spoyle and havocke of the Cohowes".

Rediscovery of the cahow

For many years, people thought any sightings of the cahow were mistakes. They believed people were confusing them with the similar Audubon's shearwater. In 1935, William Beebe hoped to find the bird again. That June, he received an unknown seabird that had hit the St. David's lighthouse in Bermuda. The bird was sent to Robert Cushman Murphy, an American bird expert. He identified it as a Bermuda petrel. Six years later, Bermudian naturalist Louis L. Mowbray received a live Bermuda petrel that had flown into a radio antenna tower. The bird was released after it recovered.

After another bird that died hitting a lighthouse was identified as a cahow, a big discovery happened. On January 28, 1951, 18 surviving nesting pairs were found on rocky islands in Castle Harbour. This discovery was made by Murphy and Mowbray. With them was a 15-year-old Bermudian boy named David B. Wingate. He would later become the main person fighting to save the bird.

Protecting the Bermuda petrel

David B. Wingate dedicated his life to saving the Bermuda petrel. After his studies, he became Bermuda's first conservation officer in 1966. He worked to solve many problems threatening the bird. This included getting rid of rats on the nesting islands. He also dealt with competition from the more aggressive white-tailed tropicbird. These tropicbirds would take over petrel nests and kill up to 75% of the chicks.

Wingate designed special wooden covers for the burrow entrances. These "bafflers" allowed the smaller petrels to enter but kept the larger tropicbirds out. Since then, almost no chicks have been lost because of tropicbirds.

Restoring Nonsuch Island

Wingate also started a project to restore Nonsuch Island. This island is near the cahow breeding islets. Nonsuch Island was almost a desert after many years of damage. The goal was not just to save what was left but to bring back what had been lost. Thousands of native plants, like Bermuda cedar (Juniperus bermudiana), Bermuda palmetto palm (Sabal bermudana), and Bermuda olivewood (Cassine laneanum), were grown and planted on Nonsuch. This helped recreate the original forest that once covered Bermuda.

In total, almost 10,000 native plants of over 100 species were planted on Nonsuch starting in 1962. These plants have now grown into a thick forest, similar to what early settlers saw in the 1600s. Wingate's main goal was to restore Nonsuch Island. This way, it could become a safe nesting place for the cahows.

Even after he retired, Wingate designed and gave artificial plastic nest boxes to the Cahow Recovery Project. These boxes were made to help the Bermuda petrel. Cahows usually nest in deep soil burrows or rock cracks. But there weren't enough good nesting spots or soil on the original islands. Artificial concrete burrows had been used, but they were very heavy and hard to build. The new plastic nest boxes were designed to fit the birds' needs. It is hoped they will help the cahow survive in the future.

Continued conservation efforts

David Wingate retired in 2000. Jeremy Madeiros then became the Bermuda Government terrestrial conservation officer. He took over managing the Cahow Recovery Program and the Nonsuch Island Living Museum Project. Madeiros found that erosion of the four small original nesting islands was the biggest threat. This erosion was caused by hurricane damage and sea level rise.

A program to band (put identification rings on) both young and adult petrels started in 2002. By 2015, over 85% of all Bermuda petrels had bands. This helps identify individual birds throughout their lives. In 2005, Madeiros published a plan to help the Bermuda petrel recover. This plan gave guidelines and goals for managing the species.

Moving chicks to new homes

It was clear that the four tiny original nesting islands were not enough. They were only about 1 hectare (2.4 acres) in total. This wasn't enough space for the species to fully recover. Madeiros, with help from an Australian petrel expert, started a project to move cahow chicks. The goal was to create a new nesting population on Nonsuch Island. Nonsuch is much larger (6.9 ha or 16.5 acres) and higher up. This makes it safer from erosion and hurricane floods. It also has room for potentially thousands of nesting pairs.

In 2004, the first trial of the project took place. Fourteen chicks were moved from the original islands to artificial concrete nest burrows on Nonsuch. This happened 18-21 days before they were ready to fly. The chicks were fed fresh squid and anchovies and watched every day until they left. All of them successfully flew out to sea. In 2005, 21 more chicks were moved, and all of them also flew successfully. This project continued for five years. A total of 105 chicks were moved, and 102 of them successfully flew to sea.

Breeding on Nonsuch Island

The first Bermuda petrels that were moved as chicks returned to Nonsuch Island in February 2008 when they were grown up. The first petrel egg on Nonsuch Island in over 300 years was laid in January 2009. The chick from that egg successfully flew away in June of the same year. By 2015, 49 of the original 102 moved birds had returned to the nesting islands. Twenty-nine of these birds returned to Nonsuch Island itself. This project has successfully created a new nesting group on Nonsuch. By 2016, this group had grown to 15 nesting pairs. This new group had already produced 46 successful chicks between 2009 and 2016.

Because the first project was so successful, Madeiros started a second one in 2013. This new project was at a different spot on Nonsuch Island. The goal was to create a second group of cahows on the island. In the first three years of this second project, 49 almost-ready-to-fly cahow chicks were moved. Forty-five of them successfully flew out to sea. In 2016, one of these birds, moved as a chick in 2013, returned. It paired up with a bird that had not been moved, in a burrow at the original moved colony on Nonsuch.

A Sound Attraction System was also set up in 2007. This system plays sounds to encourage returning birds to stay on Nonsuch. It helps them overcome any desire to go back to the busy original nesting islands.

Cahow population growth

Thanks to conservation efforts over the past five decades and strong legal protection, the Bermuda petrel population has grown a lot. In 1960, there were only 17 to 18 breeding pairs, producing 7 to 8 chicks. By 2019, there were 132 breeding pairs, producing 72 chicks!

The main challenges for the bird's future are still a lack of good nesting places. About 80% of Bermuda petrels nest in artificial burrows. Also, the original smaller nesting islands are still eroding because of hurricanes and sea-level rise. For example, Hurricane Fabian in 2003 destroyed about 15 nesting burrows. Most of the remaining ones needed urgent repairs. In 2010, Hurricane Igor caused more damage to nests. In 2014, Hurricane Gonzalo killed 5 nesting pairs that had already returned to the smaller islands.

In 2015, the total number of these birds in the world was about 300. A cahow was found and banded on Vila islet, Azores, in November 2002. It was found there again in November 2003 and December 2006. Another cahow was seen off the west coast of Ireland in May 2014. This is the furthest the species has ever been seen from Bermuda!

CahowCam outreach project

In 2011, the "CahowCam" project started. This project is run by the LookBermuda / Nonsuch Expeditions Team in partnership with the Department of the Environment and Natural Resources. Since then, it has been live streaming infrared video from special artificial nesting burrows on Nonsuch Island. These burrows use special cameras and lights built by Jean-Pierre Rouja. In 2016, they teamed up with The Cornell Lab of Ornithology. This partnership led to over 20 million minutes of CahowCam footage being watched in the next 3 seasons!

Restoring cahow homes

Cahows are a "Lazarus species" that are recovering. They need special care to help them grow. All nesting islands and nearby islands are strictly protected. They are part of the Castle Islands Nature Reserve. The public is not allowed to land there without special permission and being with a conservation officer. This area is also an "Important Bird Area" (I.B.A.). This is because it holds the entire world population of Bermuda petrels. It also has up to 20% of the North Atlantic population of white-tailed tropicbirds.

These islands are kept free of rats using a yearly baiting program. Pet animals are not allowed on any islands in the reserve. Also, there is an ongoing program to remove non-native plants that invade the islands. They are replaced with native plants, many of which are also endangered. Several nesting islands are also part of an ecological restoration project. The goal is to bring back the plant and animal communities that once lived there. These communities were largely lost from the rest of Bermuda.

Other challenges for conservation

Even though the Bermuda petrel's population has clearly increased, there are still challenges. It is predicted that the population will double every 22 years. However, the petrel is much more vulnerable now. This is due to major damage to its homes and nesting sites from tropical storms and climate change. The expected increase in strong tropical storms (Category 4 and 5) is a big threat to the petrels' long-term survival. Tropical storms also cause long-term erosion of their habitat, which makes conservation harder. Scientists are looking for other suitable areas to create artificial nesting places.

The cahow's recovery has also been slowed by competition from white-tailed tropicbirds (Phaethon lepturus) for nest sites. Also, a single snowy owl (the first ever seen in Bermuda) ate 5% of the young birds on Nonsuch Island. This owl was removed. Light pollution from a nearby airport and a NASA tracking station also affects the birds' night-time mating flights.

Another big problem for nests is competition with other birds. To fix this, artificial dome nests were made for tropicbirds in areas not used by the Bermuda petrel. Wooden baffles were also put over the entrances of petrel burrows. These baffles only let petrels enter, keeping the tropicbirds out.

Another concern is that cahows might have a higher risk of extinction. This is because they live in small areas, have small populations, and have less genetic diversity. Also, petrels tend to return to the same breeding sites every year. This means they might keep returning to places where many birds die.

Rats also swam to one breeding island in April 2005. But they were quickly removed within two weeks, and no cahows were lost. Unfortunately, this happened again in March 2008. Five chicks were killed on one of the nesting islands. Immediate baiting led to finding a dead black rat (Rattus rattus). This incident showed that constant watchfulness is needed. Fresh bait must be provided on the islands throughout the nesting season. This was further proven by more rat invasions on some nesting islands, including Nonsuch Island, in 2014 and 2015. Luckily, this time no birds were lost.

Images for kids