William Beebe facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

William Beebe

|

|

|---|---|

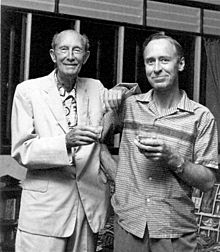

William Beebe in British Guiana in 1917

|

|

| Born |

Charles William Beebe

July 29, 1877 |

| Died | June 4, 1962 (aged 84) Simla (near Arima), Trinidad and Tobago

|

| Nationality | American |

| Known for | His deep dives in the Bathysphere; his monograph on pheasants, and numerous books on natural history |

| Spouse(s) | Mary Blair Rice, div. 1913 |

| Awards | Honorary doctorates from Tufts and Colgate University Daniel Giraud Elliot Medal (1918) Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire Medal (1921) John Burroughs Medal (1926) Theodore Roosevelt Distinguished Service Medal (1953) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Naturalist |

| Institutions | New York Zoological Park |

Charles William Beebe (July 29, 1877 – June 4, 1962) was an American naturalist, ornithologist (bird expert), marine biologist (sea life expert), entomologist (insect expert), explorer, and author. He is remembered for his many trips for the New York Zoological Society. He also made very deep dives in a special vessel called the Bathysphere. Beebe wrote many scientific books and popular articles for everyone to read.

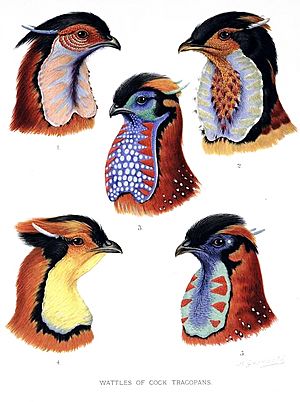

Born in Brooklyn, New York, William Beebe grew up in East Orange, New Jersey. He left college to work at the new New York Zoological Park. There, he was in charge of caring for the zoo's birds. He quickly became known for designing great homes for the birds. He also led many research trips. One big trip was around the world to study pheasants. These trips helped him write many books for both scientists and the public. His book A Monograph of the Pheasants was published in four parts from 1918 to 1922. Because of his research, he received special degrees from Tufts and Colgate University.

During his expeditions, Beebe became very interested in sea life. This led him to dive in the Bathysphere in the 1930s. He made these dives with Otis Barton, who invented the Bathysphere. They explored off the coast of Bermuda. This was the first time a biologist saw deep-sea animals in their natural home. They set new records for the deepest human dives. Beebe's deepest record lasted for 15 years. After his Bathysphere dives, Beebe went back to tropical places. He started to study how insects behave. In 1949, he started a research station in Trinidad and Tobago. He named it Simla. This station is still used today as part of the Asa Wright Nature Centre. Beebe continued his research at Simla until he died from pneumonia in 1962. He was 84 years old.

William Beebe is seen as one of the people who started the study of ecology. He was also a strong supporter of conservation in the early 1900s. He is also remembered for his ideas about how birds evolved. Many of his ideas were ahead of their time. For example, in 1915, he thought that bird flight developed from a "four-winged" stage. This idea was supported in 2003 by the discovery of Microraptor gui.

Contents

- William Beebe's Early Life and Learning

- Working at the Bronx Zoo

- Early Explorations and Trips

- The Pheasant Expedition

- Return to Guiana and World War I

- Galápagos Expeditions

- Haiti and Bermuda Research

- Research at Nonsuch Island

- Return to Tropical Research

- Final Years in Trinidad and Tobago

- William Beebe's Impact and Legacy

- How William Beebe Changed Science

- See also

William Beebe's Early Life and Learning

Charles William Beebe was born in Brooklyn, New York. His father, Charles Beebe, worked for a newspaper. When William was young, his family moved to East Orange, New Jersey. There, he became very interested in nature. He also started writing down everything he saw. The The American Museum of Natural History, which opened the year he was born, helped grow his love for nature.

In 1891, Beebe started East Orange High School. Even though his first name was Charles, everyone called him William Beebe. During high school, he loved collecting animals. He learned taxidermy to preserve them. If he couldn't find an animal himself, he would trade with other collectors. Beebe's first article was published when he was still in high school. It was about a bird called a brown creeper. It appeared in Harper's Young People magazine in January 1895.

In 1896, Beebe was accepted into Columbia University. He often spent time at the American Museum of Natural History. Many professors at Columbia also worked at the museum. He studied with Henry Fairfield Osborn, and they became close friends.

While at Columbia, Beebe convinced his professors to support his research trips. He went with other students to Nova Scotia. He continued collecting animals and tried to photograph birds. Columbia professors even bought some of his photos for their lectures. On these trips, Beebe also became interested in dredging. This meant using nets to pull up deep-sea animals. He tried to study them quickly before they died. Beebe never got a degree from Columbia. However, he later received honorary degrees from Tufts and Colgate University.

Working at the Bronx Zoo

In 1899, Beebe decided to work at the New York Zoological Park. This was instead of finishing his studies at Columbia. He was excited to be part of the new zoo. He also wanted to help his family with money.

Henry Fairfield Osborn made Beebe the assistant curator of birds. His main job was to help the zoo's birds reproduce. Beebe believed birds needed a lot of space. He suggested building a huge "flying cage" the size of a football field. It was built, but smaller than he wanted. Even so, it worked very well for the birds.

In 1901, Beebe went on his first trip for the zoo to Nova Scotia. He wanted to collect sea animals from tide pools and by dredging. The next year, he became a full curator. He held this job until 1918. After that, he was an honorary curator until 1962.

On August 6, 1902, Beebe married Mary Blair Rice. She was known by her writing name, Blair Niles. Blair often joined Beebe on his trips. As a writer, she helped him with his own books. Their honeymoon to Nova Scotia was also a chance to collect more specimens.

In February 1903, Beebe and Blair went to the Florida Keys. Beebe had a throat infection, and the warm weather was good for him. This trip was Beebe's first time in the tropics. He became very fascinated with these warm places. By the end of 1903, at age 26, Beebe had published over 34 articles and photos. He was made a fellow in the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

Early Explorations and Trips

In December 1903, Beebe went on a trip to Mexico to help his throat. He and Blair traveled on horseback and lived in tents. They carried revolvers for safety. The trip was to find and collect Mexico's birds. Beebe's first book, Two Bird Lovers in Mexico, was about this trip. It was very popular.

Beebe's second book, The Bird, Its Form and Function, came out in 1906. This book explained bird biology and evolution in a way that everyone could understand. It was a big change for Beebe. He used to love collecting animals. Now, he started to focus on wildlife conservation.

Beebe still collected animals when needed for science. But he no longer collected just to add to his collection. In 1906, he gave his collection of 990 specimens to the zoo. This was for education and research. He was made a life member of the New York Zoological Society.

In 1907, the journal Zoologica was started just for Beebe's research. The first issue had 20 papers, and Beebe wrote 10 of them. The next year, he got a promotion. This gave him two months off each year for more research trips. His first trip with this new privilege was to Trinidad and Tobago and Venezuela. He studied birds and insects. He brought 40 live birds back to the zoo.

Beebe became good friends with President Theodore Roosevelt. This friendship lasted until Roosevelt's death in 1919. Beebe admired Roosevelt's skill as a naturalist and his support for conservation. Roosevelt also admired Beebe's writing. Roosevelt often praised Beebe's books and wrote introductions for some of them.

In 1909, Beebe and Blair went to British Guiana. They hoped to set up a permanent research station there. They also wanted to find a hoatzin, a bird thought to be a link between birds and reptiles. Beebe studied hoatzin behavior closely. But they had to go home early because Blair broke her wrist. They still brought back 280 live birds for the zoo. Beebe wrote about this trip in his book Our Search for a Wilderness.

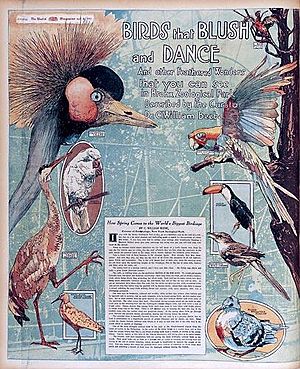

The Pheasant Expedition

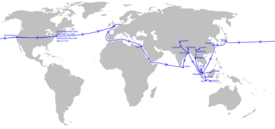

In 1909, a rich businessman named Anthony R. Kuser offered to pay for Beebe to travel the world. The goal was to study pheasants. The zoo's director, Hornaday, did not like this idea. But the zoo agreed because Beebe's past trips had helped their reputation. Lee Saunders Crandall took over Beebe's duties at the zoo. Beebe and Blair left for the trip with Robert Bruce Horsfall. Horsfall was there to draw the birds for a book.

They sailed across the Atlantic to London. Then they went through the Suez Canal to Ceylon (now Sri Lanka). There, they started studying wildfowl. From Ceylon, they went to Calcutta to find pheasants in the Himalayas. Beebe and Horsfall started to disagree. Horsfall refused to go to the western Himalayas with Beebe. Beebe continued without him. Horsfall rejoined them in Calcutta, and they sailed to Indonesia. Then they went to Singapore, where Beebe set up a base.

Next, the expedition went to Sarawak on the island of Borneo. The disagreements between Beebe and Horsfall grew worse. Beebe decided Horsfall was harming the trip and sent him home. Beebe and Blair continued to Batavia in Java, and to other islands.

After Java, they sailed north to Kuala Lumpur in Malaya. Then they went to Burma. In Burma, Beebe felt very sad for a few days. He got better by reading many adventure novels.

The last part of Beebe's journey was to China. They made an unplanned visit to Japan to escape riots and the bubonic plague. When things calmed down, Beebe returned to China to study pheasants. He then visited Japan again to study pheasants in the Imperial Preserves. In Japan, he was given two cranes in exchange for swans.

The expedition lasted 17 months. Beebe and Blair returned to New York. They had found almost all the pheasants they sought. They also had many notes on their behavior. Some pheasants, like Sclater's impeyan, had never been seen in the wild by Westerners. Beebe's observations helped him understand how sexual dimorphism (differences between male and female animals) works in pheasants. He also suggested a new way pheasants evolved. This idea, called punctuated equilibrium, was new at the time.

In January 1913, Blair left Beebe and divorced him. This was a shock to Beebe, and he was very sad for over a year. Even though she helped with the pheasant trip, Beebe removed all mention of her from his book about it.

By 1914, Beebe's pheasant book was mostly finished. He wrote the text, and several artists drew the pictures. The book was very detailed with color artwork. It was printed in London, with illustrations made in Germany and Austria. When World War I began, the printing was stopped for four years.

Return to Guiana and World War I

In 1915, Beebe went to Brazil to collect more birds for the zoo. This trip was important for him. He had more experience than the others with him, so he became a mentor. He also discovered how many different living things could be found under one tree. He started studying small areas of wilderness for a long time. This trip marked a shift from studying birds to studying tropical ecosystems.

In 1916, Beebe went to Georgetown to set up a research station in Guiana. He found a large house on a rubber plantation called Kalacoon. Soon after, Theodore Roosevelt and his family visited. Roosevelt wrote an article about the station, which helped gain public support.

The Kalacoon station allowed Beebe to study the jungle in great detail. He studied small areas of jungle, from the top of the trees to below the ground. He also studied a larger area, about a quarter-mile square. In 1916, he brought 300 live specimens back to the zoo. He finally caught a hoatzin, but it did not survive the trip back to New York.

Beebe wrote about his discoveries at Kalacoon in his 1917 book Tropical Wild Life in British Guiana. This book inspired many other researchers.

Beebe wanted to serve in World War I. At 40, he was too old for regular service. With Roosevelt's help, he became a pilot trainer on Long Island. He crashed during a landing and hurt his wrist. While his wrist healed, he returned to Kalacoon. He was sad to find that the jungle around the house had been cut down for rubber trees. This meant he had to close the station. Losing Kalacoon, along with his earlier divorce, made Beebe very sad.

In October 1917, Beebe served in the war. He flew planes to take photos of German gun positions. He also spent time in trenches. Beebe wrote articles about his war experiences for magazines. He did not always make his exact military role clear. He expressed his sadness about the war's realities.

Beebe's job at the Zoological Society changed in 1918. He became the Honorary Curator of Birds and director of the new Department of Tropical Research. This meant he no longer had to care for the zoo's animals. He could focus fully on writing and research.

The first part of Beebe's pheasant book was published that fall. It was highly praised and received the Daniel Giraud Elliot Medal in 1918. In January 1919, Roosevelt, who was very ill, wrote to Beebe to congratulate him. This was the last letter Roosevelt wrote before he died. The other parts of the book were published in 1921 and 1922. The complete work, A Monograph of the Pheasants, is considered one of the best bird books of the 20th century.

In 1919, Beebe got a new research station in Guiana called Kartabo Point. It was very good for studying wildlife in small areas. At Kartabo, Beebe discovered an "ant mill". This is when ants follow each other in an endless circle until they die from tiredness.

Galápagos Expeditions

Beebe really wanted to go to the Galápagos Islands. He wanted to find more evidence for evolution than Charles Darwin had found. In 1923, Harrison Williams paid for the trip. Beebe was given a 250-foot steam yacht called the Noma. The crew included scientists and artists. On the way, Beebe was amazed by the life in the sargassum weed in the Sargasso Sea. He spent days studying the creatures living in it.

Beebe's first Galápagos trip lasted 20 days. He studied how animals there had changed because there were no predators. The animals were not afraid of humans. This made it easy to catch live specimens for the zoo. Beebe also found a new bay on Genovesa Island, which he named Darwin Bay. He documented all the animals living there. On the way back, Beebe used new tools to dredge animals from the sea. He had a "pulpit," an iron cage at the front of the ship to see the water better. He also had a "boom walk," a 30-foot boom from the side of the ship to hang from. His book about this trip, Galápagos: World's End, was a huge success. It stayed on the New York Times best-seller list for months.

In 1924, Beebe returned to his Kartabo research station in Guiana. He continued his detailed study of the tropical ecosystem. The paper from this study was published in Zoologica in 1925. It was the first study of its kind in tropical ecology. Beebe was still sad during this trip, both about his divorce and his mother's death.

Beebe wanted to return to the Galápagos with a better research ship. In 1925, he went on a second Galápagos trip, the Arcturus Oceanographic Expedition. His ship, the Arcturus, was much larger than the Noma. It could stay at sea for long periods. The Arcturus had Beebe's pulpit and boom walk. It also had cages for live animals, chemicals to preserve dead ones, and a darkroom for photos.

The Arcturus did not find much sargassum. But Beebe and his crew successfully dredged creatures off the coast of Saint Martin and Saba. In the Pacific, they found a strange boundary between two currents with different temperatures. Many different kinds of life lived there. Beebe studied this area for days. He thought it might cause the unusual climate in South America. Beebe's study of these currents is the earliest known study of El Niño.

Near Darwin Bay, Beebe tried studying sea animals in their natural home. He went down into the ocean in a diving helmet. He continued these helmet dives throughout his trip. He found many new sea animals. He also studied a small area of the ocean for 10 days. He documented all the marine life there. This study found 3,776 fish of 136 species, many new to science.

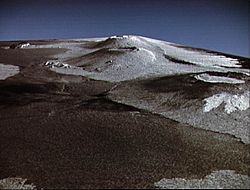

While in the Galápagos, Beebe and his crew saw a volcanic eruption on Albemarle Island. Beebe and his assistant John Tee-Van went to investigate. They found an active crater. Beebe realized the air was full of poisonous gases and barely escaped. He watched the eruption from his ship for two more days. He saw many birds and sea animals die from the lava or from trying to eat dead animals.

On the way back, Beebe still couldn't find the thick sargassum mats. To please his sponsors, he decided to study the marine life of the Hudson Gorge near New York City. He found many surprising sea animals there. Many were thought to live only in the tropics.

After this trip, Anthony R. Kuser asked Beebe to make a shorter, popular version of his pheasant book. This book, Pheasants: Their Lives and Homes, came out in 1926. It won the John Burroughs Medal. While writing it, Beebe remembered many adventures from the pheasant trip. He wrote another book, Pheasant Jungles, about these adventures. A Monograph of the Pheasants was factual. Pheasant Jungles was more like a story, with some parts changed to make it more interesting.

Haiti and Bermuda Research

In 1927, Beebe went to Haiti to study its sea life. He anchored his ship, the Lieutenant, in Port-au-Prince. He made over 300 helmet dives to explore the coral reefs and classify the fish. He used new tools: a waterproof brass box for an underwater camera and a phone in his diving helmet. This phone let him tell his observations to someone on the surface. In 100 days, his team found almost as many species as had been found on Puerto Rico in 400 years. Beebe wrote about this trip in his 1928 book Beneath Tropic Seas.

Beebe loved helmet diving. He believed everyone should try it if they could.

Beebe became good friends with the novelist Elswyth Thane. She had admired him for years. Her first novel was even about an adventurer who looked like Beebe. Beebe and Elswyth married on September 22, 1927. Beebe was 50.

Elswyth did not like the heat of the tropics. So, Beebe decided to continue his sea research in Bermuda, where they had honeymooned. Bermuda's governor, Louis Bols, introduced Beebe to Prince George. Prince George loved Beebe's books and went helmet diving with him. The governor and Prince George offered Beebe Nonsuch Island, a 25-acre island, for a research station.

With help from his sponsors, Beebe planned to study an 8-mile square area of ocean around Nonsuch Island. He wanted to document everything from the surface to 2 miles deep. However, dredging could only give a limited view of deep-sea animals. Beebe compared it to a visitor from Mars trying to learn about a foggy city by picking up trash from a street. So, Beebe started planning a device to go deep underwater and observe directly. The New York Times wrote about his plans for a cylinder-shaped diving bell.

These articles caught the eye of Otis Barton, an engineer who admired Beebe. Barton believed Beebe's design would not survive the deep ocean's pressure. He proposed a spherical vessel, which is the strongest shape for high pressure. Beebe liked Barton's idea. They made a deal: Barton would pay for the sphere and its equipment. Beebe would pay for other costs, like the ship to lower it. Barton would join Beebe on the dives. Beebe named their vessel the Bathysphere, meaning "deep sphere."

Research at Nonsuch Island

From 1930 to 1934, Beebe and Barton used the Bathysphere for many dives. They went deeper and deeper off Nonsuch Island. They were the first people to see deep-sea animals in their natural home. The Bathysphere was lowered by a steel cable. A second cable carried a phone line for talking to the surface. It also had an electric cable for a searchlight. Beebe told his observations over the phone to Gloria Hollister, his main assistant. She also prepared specimens from dredging. Beebe and Barton made 35 dives. They set several world records for the deepest human dive. Their deepest dive, to 3,028 feet on August 15, 1934, was a record until Barton broke it in 1949.

In 1931, their Bathysphere dives stopped for a year due to technical issues and bad weather. Beebe also had to leave for a week when his father died. Another year-long stop happened in 1933. This was partly due to lack of money during the Great Depression. Even without dives, their work got a lot of attention. The Bathysphere was shown at the American Museum of Natural History and the Century of Progress World's Fair in Chicago. Beebe also wrote articles about their dives for National Geographic. He even broadcast his voice from inside the Bathysphere on an NBC radio show.

Beebe tried to make sure Barton got credit as the inventor and fellow diver. But the media often focused only on Beebe. Barton sometimes felt angry, thinking Beebe was taking all the fame. Beebe found Barton's moods difficult. Still, they needed each other: Beebe for his biology knowledge, Barton for his engineering skills. They managed to work together for their dives, but they did not remain friends afterward.

Beebe continued marine research after 1934. But he felt he had seen what he wanted with the Bathysphere. Further dives were too expensive for the new knowledge they would gain. He then studied the stomach contents of tuna in the West Indies. This found new larval forms of several fish species. Soon after, Beebe went on a longer trip to Baja California. This was paid for by businessman Templeton Crocker on his yacht, the Zaca. They studied undersea animals using dredging and helmet diving. They were surprised by the many different animals they found. In 1937, Beebe went on a second trip on the Zaca. He documented wildlife along the Pacific Coast from Mexico to Colombia. On this trip, he tried to document all parts of the ecosystem, not just sea animals or birds. Beebe wrote about his Zaca trips in his books Zaca Venture and The Book of Bays. In these books, he showed his concern for threatened habitats and sadness about human destruction.

On the Zaca trips, Beebe was joined by his assistant John Tee-Van and Jocelyn Crane. Crane was a young carcinologist (crab expert) who had worked with Beebe since 1932. She became one of his most valued colleagues. Beebe also became good friends with Winnie-the-Pooh's creator, A. A. Milne. Milne wrote that he admired Beebe's qualities and the new world he explored.

Return to Tropical Research

Beebe used Nonsuch Island as his base through the 1930s. But when World War II started in 1939, they had to quickly leave their station. Transportation to Bermuda resumed in 1940, and Beebe returned in May 1941. But the war was changing the environment. Many military ships made docking hard. Most of the island's reefs were destroyed to build an airfield. Construction and pollution made studying sea life impossible. Beebe was upset by the destruction. He rented his station to a military company and returned to New York.

With the loss of their Bermuda station, Beebe and Elswyth changed their plans. Elswyth, who liked cooler places, looked for a home in New England. Beebe looked for a new tropical research station. His old station, Kartabo, had been deforested like Kalacoon. Beebe helped Elswyth buy a small farm in Wilmington, Vermont. He visited her often. Elswyth explained that she was not comfortable on Beebe's expeditions. So, they agreed to keep their careers separate from their private lives.

With money from Standard Oil and the Guggenheim Foundation, Beebe set up his next station in Caripito, Venezuela. This was about 100 miles west of Trinidad and Tobago. Beebe and his team studied the local ecology. They saw how animals were affected by wet and dry seasons. One important study showed that rhinoceros beetles use their horns to fight other males. This proved their horns were for attracting mates, not for defense. Beebe's research at Caripito was good. But he felt the extreme wet-dry cycle made it hard to work there. Also, oil operations were destroying the environment. So, Beebe did not return after his first season.

In 1944, Jocelyn Crane went to Venezuela to find a new station. She found Rancho Grande. This building was meant to be a palace for Venezuela's dictator, Juan Vicente Gómez. But it was unfinished after he died. Its huge rooms had become home to jaguars, tapirs, and sloths. Unlike Beebe's other stations, Rancho Grande was on a mountain. Beebe called it "the ultimate cloud jungle." Creole Petroleum paid for the station. They finished a small part of the building for Beebe's team. Beebe and his team started working there in 1945.

Rancho Grande was on a mountain pass in the Venezuelan Coastal Range. This was an important path for migrating butterflies. The station was great for studying insects. While working there, Beebe broke his leg falling from a ladder. Being unable to move much gave him a new way to observe wildlife. He asked to be taken into the jungle with his chair. As he sat still, wild animals soon ignored him. He spent hours watching two bat falcons through binoculars. He documented their two chicks and every prey item their parents brought. His observations found new behaviors, including the first documented example of play in birds.

Beebe and his team had good seasons at Rancho Grande in 1945 and 1946. But they did not return in 1947. They said they needed more time to analyze their findings. But it was also due to lack of money and unstable politics in Venezuela. Beebe returned in 1948. He finished papers on bird and insect migration. He also co-authored a study of the area's ecology with Jocelyn Crane. Realizing politics might end their research, Jocelyn looked for a new site in Trinidad and Tobago. When the 1948 Venezuelan coup d'état happened, Beebe decided he could no longer work in Venezuela. Beebe wrote about his experiences at Rancho Grande in his 1949 book High Jungle. This was his last major book.

In January 1950, the New York Zoological Society celebrated Beebe's 50th anniversary with them. He was the only original staff member left. He had produced more scientific papers and publicity than any other employee. Other scientists praised his work and influence. Harvard biologist Ernst Mayr said Beebe's work, especially his pheasant book and jungle books, inspired him.

Final Years in Trinidad and Tobago

Jocelyn Crane found a house in Trinidad and Tobago called Verdant Vale. It overlooked the Arima Valley. In 1949, Beebe bought this estate to use as a permanent research station. He renamed it Simla, after a hill in India from Rudyard Kipling's stories.

At Simla, Beebe and his team worked closely with Asa and Newcome Wright, who owned the next-door estate. The Wrights provided housing while Simla got water and electricity. Simla was initially 22 acres. But Beebe soon bought another 170-acre estate called St. Pat's. In 1953, Beebe gave both properties to the New York Zoological Society for one dollar. This made him a "Benefactor in Perpetuity" for the society.

Research at Simla officially began in 1950. Beebe's research there combined many of his past interests. He observed bird life cycles, studied every plant and animal in small forest areas, and looked at insect behavior. His scientific papers from this time focused on insects, marking his move into entomology. Local children often brought animals to Beebe at Simla for him to identify. He enjoyed working with them, remembering his own childhood studies.

In 1952, on his 75th birthday, Beebe retired as director of the NYZS Department of Zoological Society. He became Director Emeritus, and Jocelyn Crane became Assistant Director. In 1953, he received the Theodore Roosevelt Distinguished Service Medal for his life's work. Beebe's last big expedition was in 1955. He retraced his pheasant expedition route from 45 years earlier. He wanted to see how the bird populations were doing with human changes. Jocelyn joined him to study fiddler crabs in Asia.

In his later years, Simla became a meeting place for many biologists. Visitors included myrmecologist (ant expert) Ted Schneirla, ethologist (animal behavior expert) Konrad Lorenz, and ornithologist David Snow. Beebe had a unique way of reacting to visitors. His terrace had statues of Winnie-the-Pooh characters, a gift from A. A. Milne. If visitors recognized them, Beebe was very happy. If not, he just waited for them to leave.

Beebe stayed active even when he was old. In 1957, at 80, he could still climb slippery tree trunks to study bird nests. By 1959, he was not as strong. He focused on lab work, like taking apart bird nests to see how they were built. He also developed a throat problem called "mango mouth." This made it hard to speak, so he gave fewer lectures.

Henry Fairfield Osborn, Jr. said that in his last years, Beebe became very ill and could barely speak. However, Beebe's doctor, A. E. Hill, said Beebe remained clear-minded and could move around almost until his last day. Both agree that Beebe loved playing jokes on visitors and kept his sense of humor.

William Beebe died of pneumonia at Simla on June 4, 1962. He was buried in Mucurapo Cemetery in Port of Spain. Memorial services were held in Trinidad and Tobago and New York City. After Beebe's death, Jocelyn Crane became the director of the Department of Tropical Research. She continued to run the Simla station with Beebe's former staff.

Beebe had worried that Elswyth would write his biography. To prevent this, he left all his papers and journals to Jocelyn. After Elswyth died in 1984, Jocelyn gave Beebe's papers to Princeton University's Firestone Library. Most scholars could not use them until Jocelyn allowed writer Carol Grant Gould to write Beebe's biography. The Archives of the Wildlife Conservation Society also have collections about the Department of Tropical Research.

William Beebe's Impact and Legacy

William Beebe was very famous in the United States. He was a scientific writer who wrote for both scientists and the public. He was like Stephen Jay Gould later on. Beebe was well-known in New York City in the 1920s. He was friends with many famous people. He was not traditionally handsome, but his energy, intelligence, and charm made him stand out.

Beebe believed in a mix of Presbyterianism and Buddhism. He wanted to combine his wonder for nature with scientific understanding. He did not like using science to support political ideas, like socialism or the idea that women were less than men. He also disagreed with eugenic ideas, which were popular among some scientists then.

Beebe sometimes had problems with his bosses at the zoo. Hornaday, in particular, was annoyed by Beebe's constant requests for more money and staff. He also felt Beebe spent less time caring for the zoo itself. However, Hornaday always defended Beebe's work in public.

Beebe expected a lot from his team on expeditions. He never said exactly what he looked for in employees. But he was very loyal to those who met his standards. When his team felt too much pressure, he would announce his birthday was coming. This gave them a few days off to celebrate. Once, a scientist whispered that it wasn't Beebe's birthday. Beebe replied, "A man should have a birthday when he needs one."

How William Beebe Changed Science

William Beebe was a pioneer in ecology. His idea that living things must be understood within their ecosystems was new and very important. The method he created, studying all living things in a small area, is now a standard method in ecology. Beebe was also a pioneer in oceanography. His Bathysphere dives set an example for many researchers who followed.

Scientists like E. O. Wilson, Sylvia Earle, and Ernst Mayr have said Beebe's work inspired their careers. One of his most important influences was Rachel Carson. She saw Beebe as a friend and inspiration. Carson dedicated her 1951 book The Sea Around Us to Beebe. She wrote that his friendship helped her write the book. Beebe brought back focus to field research when lab studies were becoming more popular. Because of this, modern field researchers like Jane Goodall and George Schaller are sometimes seen as following in his footsteps.

By writing for both scientists and the public, Beebe made science easy for everyone to understand. This was especially important for conservation. He was one of the first and most important people to speak up for it. His many writings about environmental dangers helped people learn about this topic. However, writing so much for the public sometimes made other scientists see him as just a "popularizer," not a serious scientist.

During his career, Beebe wrote over 800 articles and 21 books. This includes his four-part pheasant book. A total of 64 animals were named after him. He also described one new bird species and 87 new fish species. While 83 fish were described in the usual way (with a specimen), four were described only from his visual observations during Bathysphere dives.

There is still some debate about the four fish species Beebe described only by seeing them. Normally, to name a new species, scientists need to collect and study a type specimen. This was impossible from inside the Bathysphere. Some critics said these fish were illusions from condensation on the window. Others even thought Beebe made them up. But this would go against his reputation as an honest scientist. Many of Beebe's Bathysphere observations have been confirmed by modern underwater photography. But it is still unclear if others fit any known sea animal. It's possible these animals do exist, but so much of the deep ocean is still unknown.

Besides the species he named, the crab Leptuca beebei (named by Jocelyn Crane in 1941) was named in his honor. It is commonly called Beebe's fiddler crab.

The Tetrapteryx Idea

Beebe believed one of his most important ideas was his "Tetrapteryx stage" hypothesis. This idea suggested that bird ancestors had wings on both their front and back legs. Beebe based this on seeing long feathers on the legs of some modern bird hatchlings and embryos. He thought these were atavisms, or traits from ancient ancestors. He also saw hints of leg-wings on an Archaeopteryx fossil. Beebe wrote about this idea in a 1915 paper called "A Tetrapteryx Stage in the Ancestry of Birds."

Gerhard Heilmann discussed Beebe's Tetrapteryx idea in his 1926 book The Origin of Birds. Heilmann looked at many other bird hatchlings for leg-wings but found no more evidence. He eventually rejected Beebe's idea. This was the common belief among bird experts for decades. However, Beebe continued to promote his Tetrapteryx idea even in the 1940s.

In 2003, Beebe's Tetrapteryx idea was supported by a discovery. Scientists found Microraptor gui, a small feathered dinosaur. It had asymmetrical flight feathers on both its front and back limbs. Beebe's idea is now seen as very insightful. It predicted the anatomy and gliding posture of Microraptor gui. Richard O. Prum said Microraptor gui looked like it "could have glided straight out of the pages of Beebe’s notebooks." This discovery brought Beebe's theory about leg feathers and bird flight back into focus.

William Beebe Tropical Research Station

After William Beebe died in 1962, his research station at Simla continued. It was managed by Jocelyn Crane and renamed the William Beebe Tropical Research Station. However, Jocelyn's research required her to travel often. By 1965, she had little time to run the station. By 1971, it was no longer in use and closed. Meanwhile, Asa Wright's health was failing. Her friends worried her nearby estate, Spring Hill, would be lost to developers. They created a trust to buy it and turn it into the Asa Wright Nature Center. In 1974, Beebe's Simla property was donated to the new Asa Wright Nature Center.

Now managed by the Asa Wright Nature Center, the William Beebe Tropical Research Station has been renovated. It is now active in research again and is an important meeting place for scientists. It is also a popular place for birdwatchers. They can see the same populations of hummingbirds, tanagers, and oilbirds that William Beebe studied decades ago.

See also

In Spanish: William Beebe para niños

In Spanish: William Beebe para niños

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |