Capture of the frigate Esmeralda facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Capture of the frigate Esmeralda |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Peruvian War of Independence | |||||||

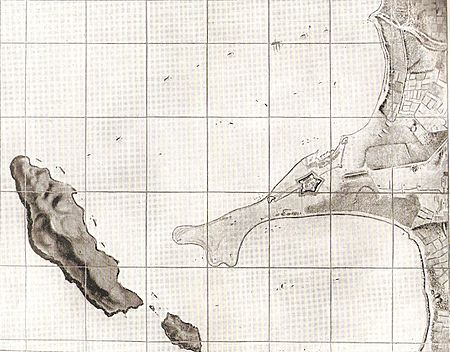

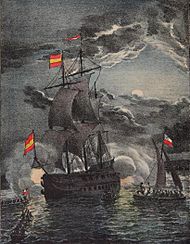

Capture of the frigate Esmeralda in the bay of Callao, L, Colet, Club Naval, Valparaíso. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Thomas Cochrane (WIA) | Antonio Vacaro Juan Francisco Sánchez Luis Coig |

||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 240 sailors & marines 14 boats |

1 frigate 2 brigs 1 pailebot 14-24 gunboats some armed merchants several harbour batteries |

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 11 killed 22 wounded |

1 frigate captured 3 gunboats captured |

||||||

The capture of the frigate Esmeralda was an exciting naval mission that happened on the nights of November 5 and 6, 1820. A group of boats filled with sailors and marines from the First Chilean Navy Squadron secretly went into Callao harbor. They were led by Thomas Cochrane. Their goal was to capture the Spanish ship Esmeralda by attacking it directly.

The Esmeralda was the most important ship of the Spanish fleet. It was also the main target of this daring plan. The Spanish had set up very strong defenses in the port to protect it.

Many historians from Chile, Spain, and Britain agree that this naval battle was a huge turning point. After this event, the Spanish Navy completely lost its power in the Pacific Ocean. This meant the Chilean Navy now controlled the seas.

Contents

Why did this happen?

On August 20, 1820, a large group of soldiers and ships, called the Liberating Expedition, left Valparaíso for Peru. General José de San Martín led the soldiers, and Vice Admiral Cochrane commanded the Chilean fleet that went with them.

From the start, San Martín and Cochrane had different ideas about how to win the war in Peru. San Martín wanted to avoid big battles. He hoped to win over the local people and slowly pressure the Spanish in Lima. Cochrane, however, wanted to strike a quick, powerful blow using both the army and navy. San Martín's plan was chosen.

The expedition arrived near Pisco on September 7. San Martín set up his base there. The Spanish leader, Viceroy Juaquin de la Pezuela, tried to talk with San Martín. But these talks, which happened in late September and early October, did not lead to peace.

In early October, San Martín sent some of his army into the Peruvian highlands. Their job was to start a revolution there.

On October 9, 1820, the soldiers in Guayaquil rebelled and declared their city independent. This was a big boost for the side fighting for freedom in Peru.

On October 26, the expedition left Pisco and sailed north. By October 29, they were in front of Callao. San Martín then moved his land forces to Ancón. Meanwhile, Cochrane took control of the island of San Lorenzo. He set up a strict blockade, meaning no ships could enter or leave Callao.

Blocking Callao Harbor

Since the freedom fighters arrived in Peru in September, the Spanish Navy had not done much. They didn't try to stop the revolutionaries or even bother them. This allowed the Chilean forces to control the sea. This was because Viceroy Pezuela wanted to play it safe and stay on defense. Also, the Spanish Navy's commander, Antonio Vacaro, was not very good at his job.

The main Spanish ships in Callao were the frigates Prueba, Venganza, and Esmeralda, along with other armed ships. The first two frigates left the port on October 10. This left the Esmeralda and other ships behind strong port defenses. These defenses included gunboats and cannons on land. Vacaro made the Esmeralda the main ship of his fleet.

This was the situation when Cochrane started blocking Callao on October 30. He had his own frigates, O'Higgins and Lautaro, and the corvette Independencia.

Cochrane's daring plan

The Chilean fleet easily kept up the blockade. But the Spanish ships did nothing, which made Cochrane impatient. He decided to take action himself.

To break the quiet blockade, he planned a big attack on the strong Spanish defenses. He wanted to do something similar to his earlier capture of the forts in Valdivia. Based on information he gathered, he decided to launch a surprise attack at night. He would enter the port with small boats and capture the Esmeralda by boarding it. He also hoped to capture or burn other Spanish ships.

Cochrane started getting ready for the attack, which he planned to lead himself. He paid attention to every small detail. For three days, the crew practiced rowing quietly and climbing up the sides of ships. They didn't know the full plan yet. On November 1, he told his officers the instructions for the attack. On the night of November 4, he even practiced a scouting trip in the bay. This was like a dress rehearsal for the real operation.

Early on November 5, the final preparations were made. Cochrane also had a speech read to his crew to get them excited and ready for the fight.

Who was fighting?

Cochrane gathered 240 men for the attack. This included 160 skilled sailors and 80 marines. Ninety-two men came from the O'Higgins, 99 from the Lautaro, and 49 from the Independencia.

Many of the crew were from different countries. Here's a quick look:

| Ship Name | Total Men | Chileans | Foreigners |

|---|---|---|---|

| O'Higgins | 92 | ? | ? |

| Lautaro | 99 | 43 (about) | 56 (about) |

| Independencia | 49 | 15 | 34 |

| Total Crew | 240 | ? | ? |

| Total Officers | 32 | 5 | 27 |

The men used 14 rowed boats, split into two groups:

- The first group had seven boats from the O'Higgins. Captain Thomas Crosbie led them.

- The second group had seven boats from the Lautaro and Independencia. Captain Martin Guise led them.

Cochrane joined the first group to lead the attack directly. Captain Robert Foster stayed behind to command the other ships.

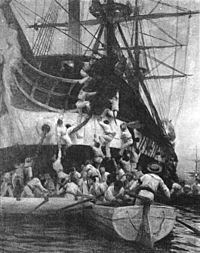

For the attack, the men carried pistols, boarding axes, daggers or machetes, and short pikes. They wore white jackets with a blue armband so they could recognize each other in the dark. If they couldn't see the armbands, they would use the secret words "Gloria" and "Victoria" as a signal.

To keep quiet, the oars of the boats were wrapped in canvas. This stopped them from making noise in the water.

The Spanish Navy in Callao, under Commander Vacaro, had:

- The main ship, Esmeralda (with 40 cannons). Captain Luis Coig commanded it.

* Besides sailors, soldiers from the Real Carlos battalion and army gunners were on board. There were 313 officers and men in total.

- The brig Maipú (16 cannons), led by Lieutenant Antonio Madroño.

- The brig Pezuela (20 cannons), led by Lieutenant Ramón Bañuelos.

- The pailebot Aránzazu (11 cannons), commanded by Juan Agustín de Ibarra.

There were also between 14 and 24 gunboats and many armed merchant ships.

In addition to the ships, the port had strong land defenses with cannons. Brigadier Juan Francisco Sánchez was in charge of these. They included:

- The fortresses of Real Felipe, San Rafael, and San Miguel.

- The batteries (groups of cannons) at the Arsenal and San Juaquín.

The Spanish had also set up a floating barrier of logs chained together. This protected the ships and only had a small opening for entry or exit. Gunboats guarded this chain. Behind it, the Esmeralda, Maipú, Pezuela, and Aránzazu were anchored. Behind them were the armed merchant ships. All these defenses were also protected by the cannons on land. It was a very strong setup!

The Battle Begins

On the afternoon of November 5, Cochrane ordered the Lautaro and Independencia to sail out to sea. He left the O'Higgins hidden near San Lorenzo Island. The boats with the attacking crew were on its hidden side. This trick made the Spanish think the main Chilean ships were leaving.

At 10 p.m., the boats left the O'Higgins. They quietly moved towards the entrance of the floating chain that protected the Spanish ships. The boats moved in two parallel lines, led by Captains Crosbie and Guise.

The Chilean force sailed along the coast near the San Juaquín battery. Then, they passed between the San Miguel fortress and where neutral ships were anchored. This hid them from view. The neutral ships, including the American USS Macedonian and the British HMS Hyperion, were very close to the opening in the Spanish defenses. The American ship wished them good luck as they passed. The British ship called out to ask who they were, but the Spanish in the port didn't hear it. This quiet journey to get close to the harbor took two hours.

At midnight, the boats reached the floating chain barrier. They saw a gunboat guarding the entrance with a lieutenant and 14 men. They quickly surprised and captured it, stopping any alarm. Then, they passed the chain. Around 12:30 a.m. on November 6, they reached the Esmeralda and boarded it from both sides at the same time. Crosbie's group, with Cochrane at the front, attacked the right side. Guise's group attacked the left side. At that moment, Captain Coig was in his cabin, and most of the crew were sleeping on deck. Only the guards were awake.

The sleepy Spanish crew quickly grabbed their weapons to fight back. But as Cochrane later said, "the Chilean machetes did not give them much time to organize." Even with the surprise, the Spanish fought bravely in some areas. There was a bloody fight with sharp weapons and guns. However, the Chilean attack was too strong. They quickly took control of the ship's quarterdeck, living quarters, and the back of the ship.

The Spanish were pushed to the front of the ship, called the forecastle. They fought bravely there until Crosbie's and Guise's forces joined together and charged. Some attackers had climbed to the ship's tops (high platforms on the masts) at the start of the boarding. They fired down from above. After taking the front of the ship, Guise cleared the lower deck of any Spanish soldiers firing up through the hatches. Shortly before 1 a.m., the attackers had taken control of the ship, and the surviving Spanish crew surrendered. During the fight, Cochrane was hit early on. Later, a shot went through his thigh. He sat on the deck and tried to direct the attack as best he could.

The fight on the Esmeralda alerted the cannons on land, the gunboats, and other ships in the port. Some Spanish sailors from the frigate jumped into the sea to escape. They told other ships that the Esmeralda had been captured.

When the fight on the Esmeralda ended, Cochrane tried to continue his plan. He wanted to attack other Spanish ships. But the sailors refused, saying they had done enough. The few sailors that officers managed to get into boats attacked the Maipú and Pezuela. But these ships were now ready and fought back, helped by several gunboats led by Vacaro. However, the Spanish commander could not get his main ship back.

Finally, Cochrane ordered Guise to take the Esmeralda out of the bay. They began to move out, along with all the small boats and two captured gunboats. One gunboat had been guarding the entrance, and another had approached the frigate during the fight. The land cannons saw what was happening and started firing to stop the Esmeralda from leaving. Other Spanish ships and gunboats also attacked it. Several shots hit the Esmeralda. One shot went through a back window, damaging the quarterdeck and killing some men. Captain Coig, who was a prisoner, was also wounded.

At this point, the neutral ships, USS Macedonian and HMS Hyperion, started moving away from the bay to get out of range of the cannons. They also put lamps in their rigging (ropes and masts) as pre-arranged signals to avoid being attacked by mistake. Cochrane saw this and understood what it meant. He ordered identical lamps to be put in the Esmeralda's rigging. This confused the Spanish cannons. They couldn't tell which of the three ships with lights was the captured frigate. They didn't want to shoot at the foreign ships. So, around 1:15 a.m., their firing began to slow down.

The Esmeralda left the port. Around 2:30 a.m., it anchored near the O'Higgins, out of range of the cannons. All the smaller boats came with it, towing the two captured gunboats. One interesting detail is that one of the O'Higgins' boats got lost. The cannons kept firing for the rest of the night, not knowing why. The mystery was solved when the sun came up. The missing boat was seen leaving the port, towing a large gunboat it had captured. It quickly received help.

What happened next?

The impact

A lasting memory

In 1855, the Chilean government decided to name a new corvette (a type of warship) Esmeralda. This was done to remember the frigate captured in this naval battle. The secret signal "Gloria" and "Victoria," used by Cochrane during the attack, also became the motto for this new corvette. This corvette made the name Esmeralda famous in the Chilean Navy's history. This was because of its brave actions in the battle of Iquique on May 21, 1879, during the Pacific War. Today, the sixth ship to carry the name is the Esmeralda (BE-43).

Chilean historian Barros Arana wrote in 1894 that this naval action has been told more times than any other battle from the Spanish American wars of independence in various history books.

See also

In Spanish: Captura de la fragata Esmeralda para niños

In Spanish: Captura de la fragata Esmeralda para niños