Chinampa facts for kids

A chinampa (pronounced chee-NAHM-pah) is a clever farming method from ancient Mesoamerica. It uses small, rectangular plots of very fertile land to grow crops right on shallow lake beds in the Valley of Mexico. The word "chinampa" comes from the Nahuatl language, meaning "in the fence of reeds."

These special farms are built in freshwater lakes or swamps. Their design helps them hold just the right amount of water for plants to thrive. This farming technique was widely used, especially in Lake Xochimilco. In 2018, the United Nations recognized chinampas as a Globally Important Agricultural Heritage System, highlighting their importance for sustainable farming.

Chinampas are sometimes called "floating gardens," but they aren't truly floating. They are actually artificial islands. To build them, ancient farmers wove reeds and stakes together under the water, creating underwater fences. Then, they piled up soil and water plants inside these fences until the top layer of rich soil appeared above the water's surface.

When chinampas were built, a smart drainage system was also created. This system had several uses. Ditches were dug between the chinampas to let water and rich sediments flow through. Over time, these ditches would collect mud. Farmers would then dig out this mud and spread it on top of the chinampas. This not only cleared the ditches but also fertilized the soil with nutrients from the lake bottom, leading to amazing harvests. This way, the soil always had fresh nutrients, helping many crops grow.

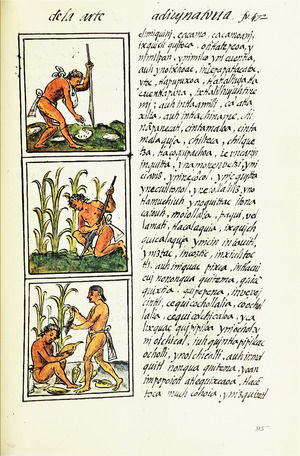

Historians have studied ancient records to understand chinampas better. For example, old Nahuatl documents from the late 1600s show that chinampas were measured in units called matl (about 1.67 meters). Some chinampas were about 30 meters long and 2.5 meters wide. In the Aztec capital, Tenochtitlan, they could be even larger, up to 90 meters long and 10 meters wide.

To make them strong, trees like āhuexōtl (a type of willow) and āhuēhuētl (a cypress) were often planted at the corners of the chinampas. These trees helped hold the soil in place. The long, raised beds were separated by channels wide enough for a canoe to pass through. These well-watered beds were incredibly productive, sometimes yielding up to seven harvests a year! Chinampas were a key part of farming in ancient Mexico and Central America. Evidence suggests that the Nahua people of Culhuacan built the first chinampas around 1100 CE.

Contents

History of Chinampa Farming

The earliest chinampa fields we know about date back to the Middle Postclassic period, between 1150 and 1350 CE. Chinampas were mostly used in Lakes Xochimilco and Chalco, where natural springs provided fresh water.

The Aztecs were very interested in these farming areas. They not only fought to control these regions but also put a lot of effort into expanding the chinampa system. Some researchers believe the Aztec government played a big role in managing water and building these farms on a large scale. This idea is sometimes called the "hydraulic hypothesis," suggesting that controlling water was important for their power.

It took a lot of people and materials to build and maintain chinampas, which supports the idea of government involvement. Also, large walls called dikes were built to keep the salty water of Lake Texcoco away from the freshwater chinampa zones. This helped the chinampas grow even larger and more productive.

Chinampa farms also surrounded Tenochtitlán, the Aztec capital, which grew significantly over time. Smaller farms were found near the island city of Xaltocan and on the east side of Lake Texcoco. When the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire happened, many dams and water gates were destroyed. This led to many chinampa fields being abandoned. However, many towns near the lakes continued to use their chinampas throughout the colonial period because this type of farming required a lot of hard work, which was less appealing to the Spanish newcomers.

The Aztecs built Tenochtitlan on an island around 1325. As their city and empire grew, they needed more space and more food. Sometimes this meant conquering new lands, and other times it meant expanding their amazing chinampa system. With multiple harvests each year, chinampas became a huge part of feeding the growing Aztec population. Farmers who worked chinampas often paid less in taxes (tribute) compared to other groups, perhaps because their food production was so vital.

Many studies have looked at how much Tenochtitlan relied on chinampas for its fresh food. These farms grew important crops like maize (corn), beans, squash, amaranth, tomatoes, chili peppers, and beautiful flowers. Farmers planted maize using a digging stick called a huictli.

The word chinampa comes from the Nahuatl words chināmitl (meaning "square made of canes") and pan (a word indicating location). Spanish writers sometimes used the word camellones, meaning "ridges between rows." However, a Franciscan friar named Fray Juan de Torquemada used the Nahua term, chinampa, explaining how easily people could plant and harvest their crops because these "strips built above water and surrounded by ditches" meant they didn't need to water them.

Chinampas are shown in ancient Aztec picture books called Aztec codices, such as Codex Vergara. They are also mentioned in written Nahuatl documents, like The Testaments of Culhuacan from the late 1500s, where people left chinampas to their families in their wills.

Today, you can still see parts of the chinampa system in Xochimilco, which is in the southern part of Mexico City. Chinampas are now seen as a great example for modern sustainable agriculture. While some experts debate how easily this ancient method can be used today, it remains an inspiring example of smart farming.

How Chinampas Were Built

According to Antonio Vera, there were two main types of chinampas: those built near the shore (inland) and those built directly on the water (irrigated). The basic idea was to create and separate shallow land by the bank or in the water. This area was then surrounded by stakes from a common wetland tree called ahuejote. Over time, as Mexico City grew, some of these traditional building methods were lost, creating new challenges for preserving this heritage.

Modern Chinampas Today

As of 1998, chinampas are still used in towns like San Gregorio, San Luis, Tlahuac, and Mixquic, all east of Xochimilco. Many of these gardens, first built and cared for from the Postclassic Period through the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire, are still active today.

However, many modern chinampas have become overgrown. Some farmers still use canoes for transport, but others increasingly rely on wheelbarrows and bicycles. Some fields, especially in San Gregorio and San Luis, have been deliberately filled in. As the canals dry up, several fields naturally join together. These dried-up areas are often used for feeding cattle instead of growing crops.

Other chinampa fields, both dry and surrounded by canals, continue to produce fresh foods. These include lettuce, cilantro, spinach, chard, squash, parsley, coriander, cauliflower, celery, mint, chives, rosemary, corn, and radishes. Young leaves of quelites and quintoniles, which are sometimes mistaken for weeds, are also grown and harvested for delicious sauces. Flowers are still a popular crop on these plots. Some chinampa fields have even become popular tourist spots!

Challenges for Chinampas

Even though many local farmers want to continue this ancient farming tradition, they face several difficulties. During the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire, many lakes, like the one at Xochimilco, were drained, which reduced the amount of land available for chinampas. Also, a major earthquake in 1985 further damaged many canals.

Other problems include a limited water supply, the use of harmful pesticides, climate change, the expansion of cities (urban sprawl), and water pollution from untreated sewage and toxic waste. These challenges make it harder to keep the chinampa system thriving.

See also

In Spanish: Chinampa para niños

In Spanish: Chinampa para niños

- Aquaponics

- Aquaculture

- Historical hydroculture

- Nanfang Caomu Zhuang, 4th-century Chinese record of floating gardens

- Waru Waru

| DeHart Hubbard |

| Wilma Rudolph |

| Jesse Owens |

| Jackie Joyner-Kersee |

| Major Taylor |