Claims to the first powered flight facts for kids

The dream of flying like a bird has fascinated humans for centuries! But who was the very first person to fly a powered airplane? This question has sparked many debates around the world. In the United States and many other countries, most people agree that the Wright Brothers made the first successful, controlled flight in 1903. However, in Brazil, many believe that their own countryman, Alberto Santos-Dumont, was the true inventor of the airplane. Let's explore the exciting history of these early flights!

Contents

Who Claimed to Fly First?

Many brave people and their supporters believed they were the first to fly a powered airplane. Here are some of the most well-known claims:

- Clément Ader with his Avion III (1897)

- Gustave Whitehead with his planes, No. 21 and 22 (1901–1903)

- Samuel Pierpont Langley's Aerodrome A (1903)

- The Wright brothers with their Wright Flyer (1903)

- Alberto Santos-Dumont with his 14-bis (1901-1906)

Other inventors also made important attempts:

- Karl Jatho in Germany (1903)

- Richard Pearse in New Zealand (1903–1904)

- Trajan Vuia in France (1906)

- Jacob Ellehammer in Denmark (1906)

Early Steps Towards Flight

Before anyone truly flew a controlled airplane, many inventors made important attempts. These early tries helped others learn what worked and what didn't.

First Powered Hops

In 1874, Félix du Temple built a steam-powered plane in France. It took off from a ramp with a sailor inside and flew a short distance. Some people called this the first powered flight. However, it wasn't a sustained flight because it used gravity to help it take off. Still, it was the first time a powered machine lifted off the ground!

Ten years later, in 1884, Alexander Mozhaysky in Russia had a similar success. His craft launched from a ramp and stayed in the air for about 30 meters (100 feet). Outside of Russia, this was not widely seen as a sustained flight.

In 1901, Wilhelm Kress built a large floatplane in Austria. It had three sets of wings and an engine. It could move well on the water, but it wasn't powerful enough to take off into the air.

The Race to Fly

Many of the claims about early powered flights were not widely known or accepted at the time. For example, the Wright brothers struggled for years to get people to believe their claims. Also, Clément Ader and Samuel Pierpont Langley didn't even claim success right after their attempts. Langley actually passed away in 1906 without ever saying he had flown.

Aviation expert Octave Chanute helped spread the word about the Wrights' work in America and Europe. They started to get some recognition in Britain. However, in 1906, the U.S. Army turned down the Wrights' offer because they hadn't publicly shown their machine could fly.

That same year, Alberto Santos-Dumont made a short flight in France with his 14-bis airplane. Because the Wrights' flights weren't widely accepted yet, Santos-Dumont was celebrated as the first person to fly! This made Ader claim that his Avion III had flown back in 1897.

Who Got the Credit?

Santos-Dumont's flight in 1906 is generally accepted as the first powered flight in Europe. However, most experts don't consider it the very first in history. Some even questioned how well his plane could be controlled.

In 1908, the Wright brothers finally started making public flights with their improved Flyer. Orville showed off their plane for the U.S. Army. Wilbur gave amazing demonstrations in France and Italy. Their flights astonished the world and helped their claims gain wide acceptance.

For a long time, the Smithsonian Institution in the U.S. didn't give credit to the Wright Brothers. Instead, they honored their former secretary, Samuel Pierpont Langley, whose 1903 plane tests failed. In 1914, an inventor named Glenn Curtiss modified Langley's old plane. Curtiss claimed he was just "restoring" it, but critics said he made big changes. He managed to make the modified plane hop a few feet off a lake.

The Smithsonian then used this to claim Langley's Aerodrome was the first plane "capable of flight." Orville Wright, who was still alive, fought hard against this. In 1928, he even sent the original Flyer to a museum in London, England, in protest. Finally, in 1942, the Smithsonian admitted Curtiss's changes and took back their claim for the Aerodrome.

After Orville Wright passed away in 1948, the Flyer returned to the U.S. and is now on display. The agreement for its return included a rule that the Smithsonian must always credit the Wrights for the first flight.

Today, most people agree that the Wright brothers were the first to make sustained and controlled powered flights. However, in Brazil, many still see Santos-Dumont as the first successful aviator because his plane took off without a special rail or catapult.

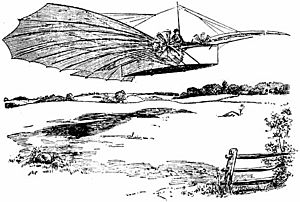

Clément Ader's Attempts

After a short hop with his first machine, the Éole, Clément Ader received money from the French army. He built two more planes, the Avion II and the larger Avion III in 1897. Neither of these planes could leave the ground.

Years later, in 1906, Ader claimed that his Éole had flown 330 feet (100 meters) in 1891. He also said the Avion III flew 1,000 feet (300 meters) in 1897. However, in 1910, the French army published a report that showed his claims for the Avion III were not true. His claims for the Éole also lacked strong proof.

Gustave Whitehead's Claims

When Gustav Weisskopf moved to the United States, he changed his name to Gustave Whitehead. He experimented a lot with gliders, engines, and flying machines. Many people claimed he made successful powered flights.

A friend of Whitehead, Louis Darvarich, said they flew a steam-powered machine in 1899. The Bridgeport Herald newspaper reported that on August 14, 1901, Whitehead flew his No. 21 plane. It supposedly reached 50 feet (15 meters) high and could be steered a little. Whitehead himself wrote letters saying he made two flights in his No. 22 machine in 1902, including flying in a circle.

Later, in the 1960s and 70s, some researchers like William O'Dwyer and Stella Randolph strongly supported Whitehead's claims. They even criticized the Smithsonian Institution for its agreement to only credit the Wright brothers. The Smithsonian strongly defended its position.

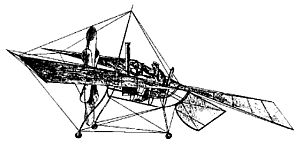

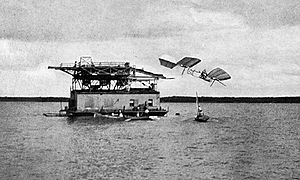

Samuel Langley's Efforts

Samuel Pierpont Langley was in charge of the Smithsonian Institution from 1887 until 1906. With support from the U.S. War Department, he worked on flying machines. His biggest project was the manned Aerodrome A. In 1903, his pilot, Charles M. Manly, tried to fly the plane from a houseboat. Both attempts, on October 7 and December 8, failed, and Manly ended up in the water each time.

The Smithsonian and Curtiss

About ten years later, in 1914, Glenn Curtiss changed Langley's Aerodrome. He flew it a few hundred feet. This was partly to help the Smithsonian save Langley's reputation. The Smithsonian then displayed the Aerodrome as "the first man-carrying aeroplane in the history of the world capable of sustained free flight." Many historians, including Fred Howard, called this statement untrue.

This action started a long disagreement with Orville Wright. It wasn't until 1942 that the Smithsonian finally admitted the changes Curtiss made. They also corrected their misleading statements about the 1914 tests.

The Wright Brothers' Flight

On December 17, 1903, near Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, the Wright brothers made history. They launched their airplane from a rail on flat ground. Orville and Wilbur took turns, making four short flights. Each flight was about ten feet high. They flew in straight lines and didn't try to turn. The plane landed on skids, as it didn't have wheels.

Wilbur's last flight was the longest, covering 852 feet (260 meters) in 59 seconds! The Flyer moved forward using its own engine power. It was not launched by a catapult that day, though they did use catapults in later tests. A strong headwind helped the plane get enough speed to fly. Pictures were taken of the plane in the air.

The Wrights kept detailed notes and photos of their work. However, they didn't share photos of their powered flights until 1908. Their written records were also kept private for a while. They were published in 1953 after their family gave them to the U.S. Library of Congress.

Newspapers in the U.S. mostly accepted the Wrights' claim, though some reports were not fully accurate at first. In 1904, they issued a statement describing their flights correctly. After a public demonstration, they decided to keep details of their machine secret to protect their patent.

In 1906, the U.S. Army still didn't believe the Wrights' claims. But by 1907, their claims were widely accepted enough for them to talk with governments in Britain, France, and Germany. In 1908, they signed contracts with the U.S. War Department and a French group. That year, their public flights amazed the world, and their claims became almost universally recognized.

Some later criticisms of the Wrights included their secrecy before 1908 and their use of a catapult for some launches. Some also said their plane was hard to control.

Alberto Santos-Dumont's Flights

Alberto Santos-Dumont was a Brazilian aviation pioneer who lived in France. He first became famous for flying airships. Then, he turned his attention to airplanes. On October 23, 1906, he flew his 14-bis biplane for 60 meters (200 feet) at a height of about five meters (15 feet). This flight was officially watched and confirmed by the Aéro-Club in France.

This flight won Santos-Dumont a prize for the first officially observed flight over 25 meters. Many aviation historians consider it the first powered flight in Europe. On November 12, he flew the 14-bis for 220 meters (720 feet) in 22.2 seconds. This earned him another prize and became the first record in the log book of the new Fédération Aéronautique Internationale (FAI).

His plane used a system where the pilot leaned to control the plane's rolling motion. Both of his flights ended when the plane started to roll, and he couldn't correct it. Some people questioned the plane's control, but this didn't stop his flight from being recognized. At that time, the Wrights' claims were not yet accepted in Europe. So, many people gave Santos-Dumont credit for the first powered flight.

Other Early Aviators

Richard Pearse

Some people in New Zealand believe Richard Pearse made the first powered airplane flight on March 31, 1903. However, Pearse himself never clearly claimed this. A researcher named Geoffrey Rodliffe stated that no serious expert believes he achieved fully controlled flight before the Wright brothers.

Karl Jatho

Karl Jatho in Germany is known for making powered hops in Hanover between August and November 1903. He claimed a hop of 18 meters (60 feet) about 1 meter (3 feet) high on August 18, 1903. He made several more short flights up to 60 meters (200 feet) long and 3 meters (10 feet) high. His plane took off from flat ground. Some people in Germany credit him with the first airplane flight, but sources disagree on how well his aircraft was controlled.

Traian Vuia

Traian Vuia is credited with a powered hop of 11 meters (36 feet) on March 18, 1906, in France. He claimed more powered takeoffs in August. His plane design was special because it showed that a heavy machine could take off on wheels. Romanian sources credit him as the first to take off and fly using only his machine's power, without a rail or catapult like the Wright brothers used. Santos-Dumont was even there to watch the March 1906 event.

Jacob Ellehammer

Jacob Ellehammer made a powered hop of about 42 meters (138 feet) while tethered (tied down) on September 12, 1906. This has been called a flight. However, Ellehammer's attempt was not officially watched. Santos-Dumont's flight, just a few weeks later, was officially observed and is given more importance.

See also

| Jessica Watkins |

| Robert Henry Lawrence Jr. |

| Mae Jemison |

| Sian Proctor |

| Guion Bluford |