Gustave Whitehead facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Gustave Whitehead

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 1 January 1874 Leutershausen, Kingdom of Bavaria

|

| Died | 10 October 1927 (aged 53) Bridgeport, Connecticut, United States

|

| Nationality |

|

| Known for | Claimed flights 1901–1902 |

| Spouse(s) | Louise Tuba Whitehead |

Gustave Albin Whitehead (born Gustav Albin Weisskopf; 1 January 1874 – 10 October 1927) was an early aviation pioneer. He moved from Germany to the United States and built gliders, flying machines, and engines between 1897 and 1915. There is a big debate about whether he flew a powered airplane successfully in 1901 and 1902. If he did, his flights would have happened before the Wright brothers' famous first flight in 1903.

Many people know about Whitehead because of a newspaper article from 1901. It said he made a powered flight in Connecticut on August 14, 1901. Over a hundred newspapers around the world shared this story. Other local newspapers also wrote about his flight experiments in the years that followed. Whitehead's aircraft designs were even mentioned in Scientific American magazine. However, his public fame faded after 1915, and he died without much recognition in 1927.

In the 1930s, new articles and books claimed that Whitehead had flown in 1901–02. These books included statements from people who said they saw his flights many years earlier. This started a big discussion among experts and aviation fans. Even Orville Wright wondered if Whitehead was first. But most historians today do not believe Whitehead was the first to fly. No clear photo exists showing Whitehead making a powered, controlled flight. However, some reports from the early 1900s said such photos were shown publicly. People have since tried to build and fly copies of Whitehead's planes.

Contents

Early life and interest in flight

Gustave Whitehead was born in Leutershausen, Bavaria, Germany. From a young age, he loved flight. He experimented with kites and was even called "the flyer." He and a friend tried to learn how birds flew by catching them, but the police stopped this.

After his parents passed away when he was a boy, he trained as a mechanic. He traveled to Hamburg and later worked on a sailing ship. This time at sea taught him more about wind, weather, and how birds fly.

Whitehead arrived in the U.S. in 1893 and changed his name to Gustave Whitehead. He worked for a toy maker in New York, building advertising kites and model gliders. He also planned to add a motor to one of his gliders. In Boston, he continued experimenting with gliders and worked at Harvard's weather station.

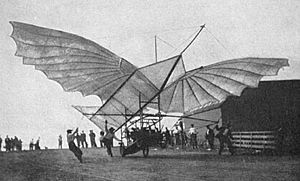

In 1896, Whitehead worked as a mechanic for the Boston aeronautical society. He built a glider and an ornithopter (a machine that flies by flapping its wings). He made a few short flights in the glider but could not get the ornithopter to fly.

Claims of powered flight

The 1899 Pittsburgh claim

A friend of Whitehead, Louis Darvarich, said in 1934 that they made a motorized flight in Pittsburgh in 1899. He claimed they flew about half a mile in a steam-powered monoplane and crashed. Darvarich said he was badly burned. Because of this, police supposedly stopped Whitehead from doing more experiments in Pittsburgh.

However, many aviation historians do not believe this story. They say there is no proof from that time. They also believe the steam engine would not have been powerful enough to lift the plane. In 1899, Whitehead was still building an aircraft, though he claimed he had flown one in Boston.

The 1901 flights

In June 1901, Scientific American magazine showed pictures of Whitehead's aircraft. It said the "new flying machine" was ready for its first tests.

Whitehead said he tested his unmanned machine on May 3. He claimed it flew 201 meters (1/8 of a mile) at a height of 12 to 15 meters (40 to 50 feet). In a second test, he said it flew 805 meters (1/2 mile) for 1.5 minutes before hitting a tree. He wanted to keep future tests secret to avoid crowds.

The most famous flight claim happened in Fairfield, Connecticut, on August 14, 1901. The Bridgeport Herald newspaper described it in detail. The article, written as an eyewitness report, said Whitehead flew his Number 21 airplane for about half a mile. It reached a height of 15 meters (50 feet) and landed safely. This flight, if true, would have been more than two years before the Wright brothers' first powered flights. Their best flight covered 260 meters (852 feet) at about 3 meters (10 feet) high.

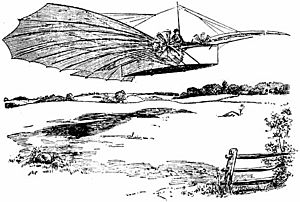

The newspaper article included a drawing of the aircraft in flight. This drawing was supposedly based on a photograph, but no such photo has ever been found. Many other newspapers around the world reprinted parts of this story.

The Bridgeport Herald reported that Whitehead's machine could also act like a car when its wings were folded. It could travel at nearly 48 kilometers per hour (30 miles per hour) on uneven roads.

Before his manned flight, Whitehead reportedly tested the plane without a pilot. He used ropes and sandbags. The newspaper said that when he was ready for his flight, "the light was good. Faint traces of the rising sun began to suggest themselves in the east."

Whitehead was quoted saying that trees blocked his path during the flight. He knew he could not fly higher or steer around them. When he reached the end of a field, he turned off the motor. The aircraft landed so gently that he was not shaken at all.

Junius Harworth, one of Whitehead's helpers as a boy, said Whitehead flew the plane at another time in mid-1901. He said it flew from Howard Avenue East to Wordin Avenue. After landing, the machine was turned around, and another short flight was made back to the start.

In September 1901, Collier's Weekly showed a picture of Whitehead's "latest flying machine." It said he "recently made a successful flight of half a mile." In November 1901, The Evening World (New York) wrote about Whitehead's achievements. It included a photo of him on his new flying machine. He was quoted saying, "within a year people will be buying airships as freely as they are buying automobiles today."

Whitehead also reportedly tested an unmanned glider during this time. It was pulled by men with ropes. A witness said it flew over telephone lines and a road, landing safely. It covered about 305 meters (1,000 feet).

The 1902 flights

Whitehead claimed two amazing flights on January 17, 1902, in his improved Number 22 plane. This plane had a more powerful 40 horsepower motor and used aluminum instead of bamboo. In letters to American Inventor magazine, Whitehead said these flights happened over Long Island Sound. He claimed the first flight was about 3.2 kilometers (two miles). The second was 11 kilometers (seven miles) in a circle, reaching heights up to 61 meters (200 feet). He said the plane, which looked like a boat, landed safely in the water near the shore.

Whitehead said he steered by changing the speed of the two propellers and using the rudder. He was proud of his achievement. He wrote, "To my knowledge it is the first of its kind." He promised photos of the Number 22 in the air, but they were never sent. He said earlier photos "did not come out right" due to bad weather.

Anton Pruckner, a mechanic who worked with Whitehead, signed a statement in 1934. He said he believed the January 1902 flight happened. He stated that Whitehead was a very truthful man and that his aircraft could fly well.

Whitehead's brother, John, visited in April 1902. He saw his brother's aircraft on the ground but not flying.

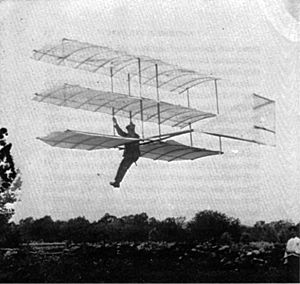

The 1903 glider flights

On September 19, 1903, Scientific American reported that Whitehead made powered glider flights. He used a triplane (three wings) machine towed by an assistant. The article said the plane "skim[med] along above the ground at heights of from 3 to 16 feet for a distance... of about 350 yards." It had a 12 horsepower motor that powered a propeller.

Aerial machines

Whitehead built many airplanes. Some sources say he built "fifty-six airplanes" by the end of 1901.

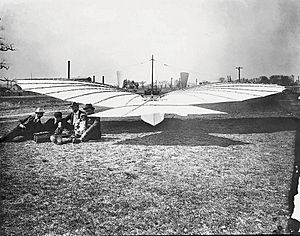

His Number 21 monoplane had a wingspan of 11 meters (36 feet). Its wings were covered in fabric and had bamboo ribs. They were similar to the wings of the Lilienthal glider. The plane had two engines. A 10 horsepower engine helped the front wheels get up to speed for takeoff. A 20 horsepower acetylene engine powered two propellers that spun in opposite directions for stability.

Whitehead described his No. 22 aircraft in a letter in April 1902. He said it had a five-cylinder, 40 horsepower kerosene motor he designed. It weighed 54 kilograms (120 pounds). The plane was 4.9 meters (16 feet) long and made mostly of steel and aluminum. Its wing ribs were steel tubing, not bamboo like the No. 21. The wings could be folded up against the body. The propellers were 1.8 meters (6 feet) wide, made of wood, and covered with thin aluminum.

In 1905, he and Stanley Beach worked together on a patent for an "improved aeroplane." Whitehead also built gliders until about 1906 and was photographed flying them.

Later career and inventions

Besides flying machines, Whitehead also built engines. In 1904, he showed an aeronautical motor at the St. Louis World's Fair. He was very skilled mechanically. He could have become rich building lightweight engines, but he was more interested in flying. He only took enough engine orders to fund his aviation experiments.

His work was described in a 1904 book called Modern Industrial Progress. The book mentioned his experiments with a "three-deck machine" and a 12 horsepower motor.

In 1908, Whitehead designed a 75 horsepower lightweight engine. He formed Whitehead Motor Works, which built motors in different sizes.

Whitehead was not good at business. He was sued by a customer and had to hide his tools. He continued his aviation work anyway. One of his engines was used in a helicopter, but it did not fly.

In 1911, Whitehead designed a helicopter with 60 blades. It lifted itself off the ground without a pilot.

He faced challenges, including an injury that affected his health. Despite this, he showed an aircraft in New York as late as 1915. He continued to invent things, like a braking safety device for railroads. He also built a machine to lay concrete. These inventions did not bring him much money. Around 1915, he worked as a laborer and repaired motors to support his family.

Gustave Whitehead died of a heart attack on October 10, 1927. He collapsed after trying to lift an engine out of a car he was fixing.

Rediscovery of his work

Whitehead's work was mostly forgotten after 1911. But in 1935, an article in Popular Aviation magazine brought new attention to him. Stella Randolph and Harvey Phillips wrote the article. Randolph later wrote a book, Lost Flights of Gustave Whitehead, in 1937. She found people who knew Whitehead and had seen his machines. She collected 16 statements from 14 people. Some said they did not see flights, but others said they saw flights of different lengths.

In 1963, Air Force major William O'Dwyer found old photos of a Whitehead biplane. He then investigated Whitehead's claims and became convinced that Whitehead flew before the Wright brothers. O'Dwyer and Randolph later wrote a book criticizing the Smithsonian Institution. They said the Smithsonian had an agreement with Orville Wright's family to only credit the 1903 Wright Flyer as the first powered controlled flight.

In 1968, Connecticut officially called Whitehead the "Father of Connecticut Aviation." But North Carolina disagreed in 1985, saying there was no proof for Whitehead's claims.

In 2013, Jane's All the World's Aircraft, a well-known aviation publication, published an article. It said Whitehead was the first to make a powered controlled flight. This started the debate again. Connecticut then created "Powered Flight Day" to honor Gustave Whitehead. However, the claim in Jane's was later questioned when a researcher showed that a key photo used as evidence was actually of a different glider.

Evidence for flights

Claimed witnesses

The Bridgeport Herald article named Andrew Cellie and James Dickie as witnesses to Whitehead's August 1901 flight. However, James Dickie later said in 1937 that he was not there and thought the newspaper story was "imaginary." He also said he did not know Andrew Cellie.

O'Dwyer believed Dickie's later statement was not reliable. He found that Andrew Cellie was likely Andrew Suelli, Whitehead's neighbor. Suelli's former neighbors told O'Dwyer that Suelli "always claimed he was present when Whitehead flew in 1901."

Junius Harworth and Anton Pruckner, who sometimes worked for Whitehead, also said they saw him fly on August 14, 1901. Anton Pruckner also said he believed in the January 1902 flight over Long Island Sound.

Whitehead claimed he made four flights on August 14, 1901, with the longest being 1.5 miles. Witnesses reported seeing several different flights that day.

Other witnesses signed statements saying they saw more powered flights in 1902. Elizabeth Koteles said she saw a flight 1.5 meters (5 feet) off the ground for 45 to 76 meters (150 to 250 feet). Many others reported seeing short flights in 1901–02.

O'Dwyer organized a survey of people who might have seen the flights. Out of about 30 people interviewed, 20 said they had seen flights. Eight had heard about them, and two said Whitehead did not fly.

Photos

No clear photo has been found showing a manned Whitehead machine in powered flight. However, some reports said such photos existed. A 1904 newspaper reported that pictures were shown in a store window in Bridgeport. They supposedly showed Whitehead in his airplane "about 20 feet from the ground and sailing along."

A blurred photo of an unmanned Whitehead aircraft in flight was shown at an Aero Club exhibit in 1906. An article in Scientific American mentioned it. Some experts believe this might have been a photo of one of Whitehead's gliders.

In 2013, a researcher named John Brown claimed that a zoomed-in part of a panoramic photo from the 1906 exhibit showed Whitehead's No. 21 in powered flight. He said it matched the drawing from the 1901 Bridgeport Herald article. However, another historian, Carroll Gray, disagreed. He showed that the image was actually a photo of a different glider, The California, from an exhibit in a park.

Replica aircraft

To see if Whitehead's No. 21 aircraft could have flown, a science teacher named Andy Kosch built a copy. He used existing photos and blueprints. This replica used modern engines and had some changes. On December 29, 1986, Kosch flew the replica about 100 meters (330 feet) at 1.8 meters (six feet) high.

In 1998, another copy of the No. 21 was flown 500 meters (1,640 feet) in Germany. This reproduction also used modern materials and engines. However, the director of the aerospace department at Deutsches Museum said that a replica flying does not prove the original flew.

Honors

Connecticut Governor John N. Dempsey named August 14 as "Gustave Whitehead Day" in 1964 and 1968. A special headstone was placed on his grave in 1964. It honored Whitehead as the "Father of Connecticut Aviation." His daughters and his assistant Anton Pruckner were there.

The "Aviation Pioneer Gustav Weißkopf Museum" opened in Leutershausen, Germany, in 1974.

A memorial fountain and sculpture honoring Whitehead was dedicated in Bridgeport in May 2012.

On June 25, 2013, Connecticut Governor Dan Malloy signed a law. It recognized Gustave Whitehead as the first person to achieve powered flight in the state.

See also

In Spanish: Gustave Whitehead para niños

In Spanish: Gustave Whitehead para niños

- History by Contract

- Early flying machines

- Timeline of aviation

- List of firsts in aviation

- List of years in aviation

- List of German inventors and discoverers

Images for kids

| Lonnie Johnson |

| Granville Woods |

| Lewis Howard Latimer |

| James West |