Early flying machines facts for kids

Imagine a time when people could only dream of flying! Early flying machines are all the amazing inventions and ideas people had about flight before modern airplanes became common around 1910. The journey to flying started thousands of years ago, long before the first successful airplane with a pilot.

Contents

Early Dreams of Flight

Flying in Stories and Myths

For thousands of years, people have dreamed of flying! Many ancient stories and myths tell of humans using special devices to soar through the sky. One famous tale from Greek mythology is about Daedalus. He supposedly made wings from feathers, thread, and wax to fly like a bird. Other legends include the Indian Vimana, a flying palace, and stories about magic carpets. There's also the tale of Kay Kāvus, a Persian king who had a throne pulled by eagles that could fly him to China!

First Tries at Flying

Around 400 BC, a clever Greek thinker named Archytas might have built the first self-moving flying machine. It was a bird-shaped model, possibly powered by steam, that flew about 200 meters! He called it The Pigeon.

Later, people tried to build wings and jump from high places like towers. They didn't yet understand how things like lift (what makes an object go up) or stability (staying balanced) worked. Many of these early tries led to accidents. In China, around 1 AD, Emperor Wang Mang had a scout try to glide with bird feathers, and he reportedly flew about 100 meters. In 559 AD, Yuan Huangtou also made a jump from a tower and landed safely.

Around 875 AD, a scientist from Spain named Abbas ibn Firnas tried to glide. He covered himself with feathers and attached wings to his arms. Reports say he flew a good distance in Córdoba, Spain, but had a rough landing because he didn't have a tail like birds do to help them land.

In the 11th century, a monk named Eilmer of Malmesbury also tried flying. He attached wings to his hands and feet and flew a short way. He also had a difficult landing, perhaps because he forgot to add a tail to his design.

Kites: Early Flying Toys and Tools

The amazing kite was invented in China, possibly as early as 500 BC! People like Mozi and Lu Ban made them from silk stretched over bamboo frames. Early Chinese kites were flat and often shaped like rectangles. Later, some kites were made to look like birds or insects, and some even had whistles to make music in the sky.

Kites weren't just for fun. In 549 AD, a paper kite was used to send a message during a rescue. Kites were also used to measure distances, check wind, send signals, and even lift people for military purposes.

When kites reached India, they became fighter kites. These small kites are controlled by pulling their string, and some even have special lines to try and cut down other kites in the air.

Kites traveled all over the world, even to New Zealand! In some places, they were used in special ceremonies. By 1634, kites arrived in Europe, appearing in books with pictures of diamond-shaped kites.

Kites That Carried People

Imagine a kite big enough to carry a person! These were used in ancient China for different reasons, including military tasks. Stories from Japan also mention man-carrying kites, and there was even a law against them at one point.

In 1282, the famous explorer Marco Polo saw how the Chinese used these kites. He described how a person would be tied to a large kite to see if it was safe for ships to sail. The way the kite flew would help them decide.

Spinning Wings: The First Helicopters?

Did you know that the idea of a helicopter is very old? Since the 4th century AD, people in China played with a toy called a bamboo-copter. You spin a stick attached to a rotor, and it flies up! This toy uses the same idea of a spinning rotor to create lift (the force that makes things go up). A book from around 317 AD even talks about "flying cars" that might have used spinning blades.

Similar spinning toys also appeared in Europe in the 14th century.

Floating High: Hot Air Balloons

The Chinese knew a long time ago that hot air goes up. They used this idea to make small hot air balloons called sky lanterns. These are paper balloons with a small lamp inside that heats the air, making them float. Sky lanterns are still used today for fun and during festivals. It's said that a general named Zhuge Liang even used them to scare his enemies in battle!

Some evidence suggests that the Chinese might have also figured out how to steer balloons many centuries before the 1700s.

New Ideas in the Renaissance

During the Renaissance, smart thinkers started to understand the science behind flight. Some early designs for flying machines were powered by people or by springs. In 1250, an English thinker named Roger Bacon even wrote about a flying machine that would flap its wings like a bird, called an ornithopter.

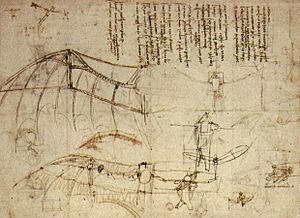

Leonardo da Vinci's Flying Machines

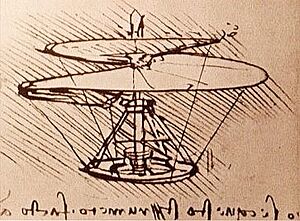

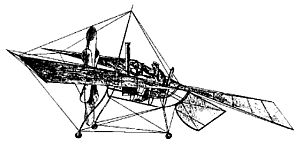

The famous artist and inventor Leonardo da Vinci spent many years studying how birds fly. He figured out many important ideas about aerodynamics, which is the study of how air moves around objects. He knew that if you push on the air, the air pushes back! From the late 1400s, Leonardo drew many designs for flying machines. These included machines with flapping wings (ornithopters), gliders, and even early helicopter-like devices.

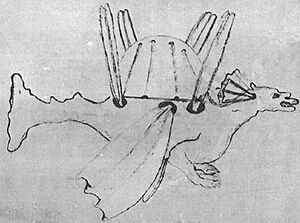

In 1488, Leonardo drew a hang glider that looked like a bird's wings. His drawings show that his designs could have worked, but he never actually flew in one himself. He even wrote about building a flying machine called "the bird" and planned to try to fly it in 1496. Some of his ideas, like a four-person "aerial screw" (like a helicopter), had problems. Leonardo's amazing ideas about flight were mostly unknown for hundreds of years, so they didn't help other inventors until much later.

More Early Flight Attempts

In 1496, a man named Seccio tried to fly in Nuremberg and had an accident. In 1507, John Damian jumped from Stirling Castle with wings made of chicken feathers. He also had an accident, and joked that he should have used eagle feathers instead!

The first idea for a jet flight might have come from the Ottoman Empire. In 1633, a person named Lagâri Hasan Çelebi reportedly used a rocket to try to fly.

In 1793, Spanish inventor Diego Marín Aguilera jumped from a castle with his glider. He flew about 5 or 6 meters high and glided for about 360 meters! In 1811, Albrecht Berblinger built a flapping-wing machine and jumped into the Danube river.

Lighter-Than-Air Flight

The Age of Balloons

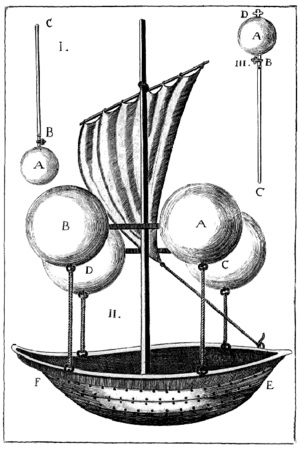

The scientific study of lighter-than-air flight began in the 1600s. Galileo Galilei showed that air actually has weight! In 1670, Francesco Lana de Terzi suggested using hollow metal spheres with no air inside to make a flying machine. These spheres would be lighter than the air around them and could lift an airship. He also thought of ways to control height, like dropping weight to go up or letting air out to go down. These ideas are still used today!

The first recorded balloon flight in Europe was a small paper hot-air balloon made by Bartolomeu de Gusmão in Lisbon in 1709. It floated about 4 meters high in front of the king!

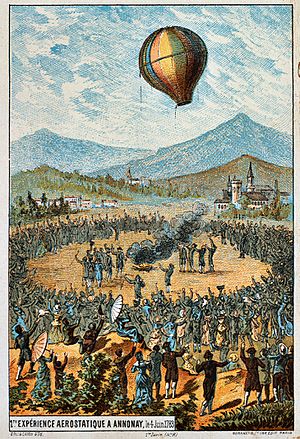

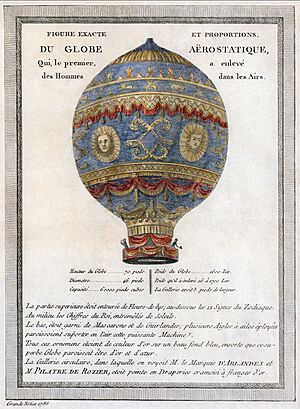

In the mid-1700s, the Montgolfier brothers in France started experimenting with balloons. They used paper balloons and filled them with hot, smoky air, which they called "electric smoke." In 1782, they successfully flew a balloon to a height of 300 meters! This amazing feat led them to be invited to Paris for a public demonstration.

Around the same time, the gas hydrogen was discovered. Joseph Black suggested using it to lift balloons. When the Montgolfier brothers were invited to Paris, Jacques Charles and the Robert brothers quickly developed a special rubber-coated silk material to hold hydrogen gas for their own balloon.

The year 1783 was amazing for balloons! Many important "firsts" happened in France:

- On June 4, the Montgolfier brothers sent up an unmanned hot air balloon with a sheep, a duck, and a chicken!

- On August 27, Jacques Charles and the Robert brothers flew an unmanned hydrogen balloon.

- On October 19, the Montgolfiers launched the first tethered (tied down) balloon with people on board.

- On November 21, the Montgolfiers made the first free flight with human passengers! Pilâtre de Rozier and the Marquis d'Arlandes flew for 25 minutes, traveling about 9 kilometers. King Louis XVI first suggested that people who were in prison could be the first pilots, but these two brave men asked for the honor instead.

- On December 1, Jacques Charles and Nicolas-Louis Robert flew a manned hydrogen balloon for over 2 hours, covering 22 miles!

The Montgolfier balloons had some challenges, like needing dry weather and sparks from the fire sometimes catching the paper on fire. The pilots even carried water to put out small fires! Charles's hydrogen balloon design was more like modern balloons. Because of these pioneers, hot air balloons became known as Montgolfière and gas balloons as Charlière.

In 1784, Charles and the Robert brothers made an improved balloon that could travel over 100 kilometers. It was designed to be more steerable, even though its human-powered propellers didn't work very well.

In 1785, Jean Pierre Blanchard and John Jeffries made the first balloon crossing of the English Channel. Sadly, another attempt to cross the Channel the other way ended in an accident. Pilâtre de Rozier tried to make a special balloon, called a Rozière, that used both hot air and hydrogen gas. His idea was to use hydrogen for steady lift and hot air to change height and find the best winds. But shortly after takeoff, the hydrogen caught fire, and there was a terrible accident.

Ballooning became very popular in Europe, helping people understand more about the atmosphere high above the Earth. By the early 1900s, it was a fun sport in Britain. These balloons often used coal gas, which was easier to find than hydrogen, even though it didn't lift as much.

Balloons were also used by armies. During the American Civil War, the Union Army Balloon Corps used tethered balloons for observation. Later, Ferdinand von Zeppelin, who would become famous for his airships, took his first balloon ride as a military observer in 1863.

Steerable Balloons: Airships!

People kept working on making balloons that could be steered, which we now call airships. On September 24, 1852, Henri Giffard made what's thought to be the first controlled, powered flight in history! He flew his airship, filled with hydrogen and powered by a small steam engine, about 17 miles from Paris, France.

In 1863, Solomon Andrews flew his own steerable airship in New Jersey. His design didn't need an engine; it used gravity and changes in lift to move forward by rising and sinking.

On August 9, 1884, Charles Renard and Arthur Constantin Krebs made the first fully controllable free flight in their electric-powered airship, La France. It flew 8 kilometers in 23 minutes and even returned to its starting point! This was a big step forward.

These early airships were often fragile and couldn't carry much weight. It was hard to make them big enough for useful tasks.

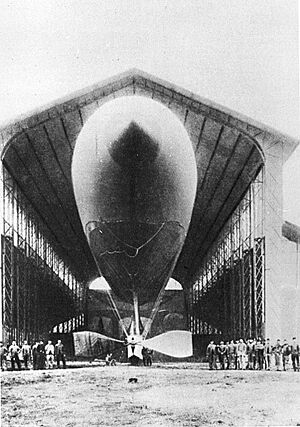

Ferdinand von Zeppelin had a great idea: a rigid outer frame would make airships much bigger and stronger. His company, Zeppelin, launched its first rigid airship, the LZ 1, on July 2, 1900. It flew for 18 minutes and later broke speed records!

The Brazilian inventor Alberto Santos-Dumont became famous for designing and flying his own steerable airships. In 1901, he won a prize by flying his No. 6 airship from Saint-Cloud, around the Eiffel Tower, and back! This showed that airships could be a practical way to travel.

Heavier-Than-Air Flight

Parachutes: Safe Landings

Leonardo da Vinci actually designed a pyramid-shaped parachute centuries ago, but his ideas weren't known at the time. The first published design for a parachute came from Fausto Veranzio in 1595. It looked like a ship's sail, with a square frame and ropes to hold the person.

In 1783, Louis-Sébastien Lenormand made the first witnessed parachute jump from a tower in France. He used a 14-foot parachute with a strong wooden frame.

Later, Louis Charles Letur created a parachute-glider that looked like an umbrella with small wings. Sadly, he had an accident in 1854.

More Heavier-Than-Air Ideas (1600s-1700s)

In the 1600s, scientists like Giovanni Alfonso Borelli and Robert Hooke realized that human power alone wasn't enough for sustained flight. Hooke even built a small, spring-powered model of a flapping-wing machine that reportedly flew.

Many people tried to design flying machines, often with flapping wings powered by springs or people. Tito Livio Burattini and Bartolomeu de Gusmão were among these early designers. Small models of helicopters also appeared, like one from Mikhail Lomonosov in 1754. While some small models flew, no full-size flying machines worked yet.

In 1647, Italian inventor Tito Livio Burattini built a model aircraft with four glider wings. It was said to have lifted a cat in 1648! His "Dragon Volant" was one of the most advanced airplane designs before the 1800s.

Bartolomeu de Gusmão also designed a bird-shaped glider called "Passarola" in 1709. He showed a small model to the Portuguese king, but never built a full-size one that flew.

In 1716, Emanuel Swedenborg drew a "Sketch of a Machine for Flying in the Air." He knew it wouldn't fly with human power, but he believed someone would eventually solve the problem. His design was considered the first sensible idea for an airplane.

The idea of spinning wings for vertical flight continued. In 1754, Mikhail Lomonosov showed a small, spring-powered model with two rotors spinning in opposite directions, a design still used today! In 1784, Launoy and Bienvenu made a flying model that is now seen as the first powered helicopter.

People still tried to fly with human power. In 1808, Jacob Degen built a flapping-wing machine. When it didn't fly on its own, he added a small hydrogen balloon, and it made some short jumps. In 1811, Albrecht Berblinger tried a similar machine without a balloon and ended up in the Danube River. This event actually inspired George Cayley to share his scientific findings, which helped start the modern age of aviation.

The 1800s: A Scientific Approach to Flight

In the 1800s, people stopped jumping from towers and started to seriously study the science of heavier-than-air flight.

Sir George Cayley: Father of the Airplane

Sir George Cayley is often called the "father of the airplane." In the late 1700s, he began the first serious study of the physics of flight (how things fly). His amazing contributions include:

- Explaining the basic rules of heavier-than-air flight.

- Understanding how birds fly.

- Doing scientific tests to show drag (air resistance) and how curved wings create more lift.

- Describing the modern airplane design: fixed wings, a body (fuselage), and a tail.

- Showing how gliders could carry people.

- Explaining the importance of power-to-weight ratio for flight.

From a young age, Cayley studied bird flight. His notebooks show he was already figuring out how wings create lift in the early 1790s.

In 1796, Cayley made a model helicopter, similar to the Chinese flying top. He believed helicopters were great for vertical flight. Later, in 1854, he made an improved model that could fly over 90 feet high!

Cayley also used a "whirling arm" test rig to study aerodynamic drag (air resistance). Instead of building full models, he tested small wing shapes on the arm to see how air affected them.

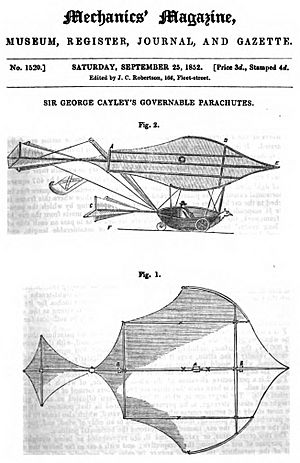

In 1799, Cayley drew the idea of a modern airplane: a machine with fixed wings, separate parts for lift, movement, and control. His sketch showed curved wings, a tail, and a body for the pilot, all designed for stability.

In 1804, he built a model glider that looked like a modern airplane, with a wing at the front and an adjustable tail at the back. It flew beautifully down hillsides and showed how important the tail was for control.

By 1809, Cayley built the world's first full-size glider, which he flew as a kite. He also wrote an important paper called "On Aerial Navigation." In it, he explained the four main forces on an aircraft: thrust (forward push), lift (upward push), drag (air resistance), and weight. He knew that human power wasn't enough and even described how an internal combustion engine could work, though he couldn't build one himself.

In 1848, Cayley built a large glider that could safely carry a child. A local boy flew in it, making him one of the first people to fly in a glider!

In 1853, Cayley built a glider that launched from a hilltop and carried the first adult pilot across a valley. We don't know the pilot's name, but this glider was the first truly modern and working heavier-than-air craft, with clear wings, a body, a tail, and controls for the pilot.

Cayley also invented the rubber-powered motor for models and even improved the design of the wheel, making it lighter for aircraft.

Steam Power Takes Flight

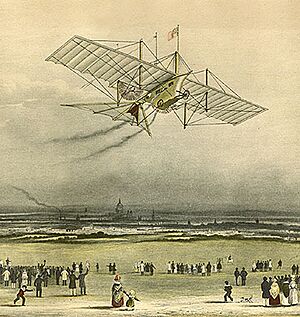

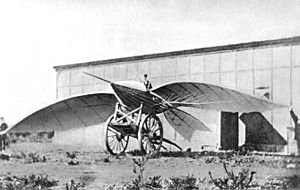

Inspired by Cayley, William Samuel Henson designed an "aerial steam carriage" in 1842. It was a large airplane with a steam engine powering two propellers. Small models of his design flew, making it the first idea for a propeller-driven airplane.

In 1856, Jean-Marie Le Bris flew his glider, "L'Albatros artificiel," higher than where he started. A horse pulled it on a beach, and he reached 100 meters high, flying 200 meters!

In the late 1850s, Félix du Temple and his brother built flying models powered by clockwork and small steam engines. One model, weighing only 1.5 pounds, was able to fly and land.

Francis Herbert Wenham studied curved wings even more deeply than Cayley. He built gliders with many wings and realized that long, thin wings were better for flight. This idea is now called the aspect ratio of a wing.

Many smart people, often called "gentleman scientists," worked on flight in the late 1800s. Matthew Piers Watt Boulton wrote about how to control an aircraft sideways and was the first to patent an aileron system in 1868. Ailerons are movable parts on wings that help steer.

In 1865, Louis Pierre Mouillard wrote an important book called The Empire of the Air, inspiring many.

In 1866, the Aeronautical Society of Great Britain was founded. Two years later, the first airshow was held in London, where John Stringfellow won a prize for the best steam engine for flying.

In 1871, Wenham and Browning created the first wind tunnel. This amazing tool helped scientists test wing shapes and learn that curved wings created much more lift than flat ones. This showed that building practical flying machines was possible!

Alphonse Pénaud was a French inventor who made big steps in flight. In 1871, he flew the first stable model airplane, called the "Planophore," for 40 meters. His model used ideas from Cayley, like a tail and angled wings for stability, and was powered by rubber bands.

By the 1870s, lighter steam engines were finally ready to be tested in aircraft.

In 1874, Félix du Temple made a short "hop" with a full-size airplane he built. His "Monoplane" was made of aluminum and was the first successful powered hop in history!

In 1875, Thomas Moy built an unmanned steam-powered aircraft called the Aerial Steamer. It was tested on a circular track and is believed to be the first steam-powered aircraft to lift off the ground on its own.

Pénaud also designed an advanced "amphibian" airplane (that could land on land or water), even though it was never built. It had many modern features like a retractable landing gear and an enclosed cockpit.

Another French inventor, Victor Tatin, flew a model airplane in 1879. It was powered by compressed air and had two propellers at the front.

In Russia, Alexander Mozhaiski built a steam-powered airplane in 1884. It launched from a ramp and flew for 98 feet.

In France, Alexandre Goupil published his ideas on "Aerial Locomotion" in 1884, but his flying machine didn't work.

Sir Hiram Maxim, an American inventor living in England, built a huge test machine in 1894. It had a wingspan of 105 feet and was powered by two steam engines. It ran on a track, and in one test, it created so much lift that it broke a rail! Maxim later worked on smaller designs.

Clément Ader built a bat-winged airplane called the Éole in 1890. It made a short, uncontrolled hop, making it the first heavier-than-air machine to take off using its own power. However, his larger Avion III in 1897, with two steam engines, did not fly successfully.

Learning to Glide Safely

In 1879, the Biot-Massia glider, which looked like a bird, flew briefly. It's now in a museum in France and is one of the oldest human-carrying flying machines still around.

Towards the end of the 1800s, important people like Horatio Phillips, Otto Lilienthal, and Octave Chanute were making big progress. Lilienthal, known as the "Glider King," built many gliders from 1891 to 1896. He made thousands of flights, testing his ideas about how birds fly.

Phillips used a wind tunnel to study aerofoil shapes (the cross-section of a wing). His research proved how wings create lift and helped design all modern wings.

The 1880s saw the creation of the first truly practical gliders. John J. Montgomery built a modern glider in 1883 and claimed successful flights in California. Wilhelm Kress also built a hang-glider in 1877.

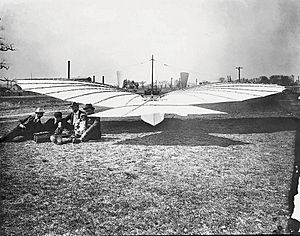

Otto Lilienthal was called the "Glider King" because he made over 2,000 controlled glides starting in 1891. He was the first person to regularly fly a heavier-than-air machine and be photographed doing it! He wrote a book called Birdflight as the Basis of Aviation and believed in practicing with gliders before trying powered flight. Sadly, he died in a glider accident in 1896 while working on powered gliders.

Octave Chanute continued Lilienthal's work, developing and testing many gliders in 1896. He was very interested in making aircraft stable and easy to control, which was a big challenge. He shared his research with other inventors around the world.

In Britain, Percy Pilcher also built and flew several gliders in the 1890s. He even built a prototype powered aircraft in 1899 that could have flown, but sadly, he died in a glider accident before he could test it.

Books like Octave Chanute's Progress in Flying Machines (1894) helped spread knowledge about flight to many people.

The Australian Lawrence Hargrave invented the box kite, which was very stable. In 1894, he linked four of his kites, added a seat, and flew 16 feet! He showed that safe and stable flying machines were possible. Hargrave shared all his inventions freely to help others make progress.

Octave Chanute believed that airplanes with multiple wings, like biplanes (two wings), were best. He developed strong, lightweight wing structures that became very popular for many years.

In 1905, Daniel Maloney was carried by a balloon to 4,000 feet in a glider designed by John Montgomery. He then glided down safely in public demonstrations. Sadly, during one flight, a rope hit the glider, causing an accident.

Adding Engines: The Race for Powered Flight

Gustave Whitehead's Claims

Gustave Whitehead was an inventor who built flying machines and engines from 1897 to 1915. He claimed to have made a controlled, powered flight in his Number 21 monoplane in Connecticut on August 14, 1901. He also claimed two more flights in 1902, flying in a circle for 10 kilometers.

However, most aviation historians, including the Smithsonian Institution, do not agree that Whitehead's flights happened as reported. There is still debate about whether his claims are true.

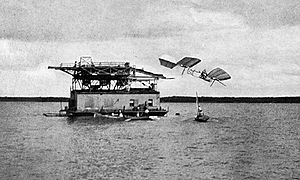

Samuel Langley's Aerodromes

Samuel Pierpont Langley was an astronomer who became interested in flight. In 1891, he published his research on aerodynamics. On May 6, 1896, his unmanned, engine-powered Aerodrome No. 5 made the first successful sustained flight of a large heavier-than-air craft. It flew over 1,000 feet! Another model, Aerodrome No. 6, flew even further and was seen by Alexander Graham Bell.

After these successes, Langley received money from the U.S. government to build a full-size airplane that could carry a person. He built a smaller "Quarter-scale Aerodrome" first, which flew successfully in 1901 and 1903.

Langley then focused on finding a powerful engine. His assistant, Charles M. Manly, designed a strong 52-horsepower engine, which was a big achievement for the time.

However, the full-size Aerodrome was too fragile. In late 1903, two attempts to launch it ended with the aircraft crashing into the water. The pilot, Manly, was rescued safely each time. The plane also lacked good controls for the pilot.

Langley's efforts ended after these failures. Just nine days after his last attempt, the Wright brothers made their famous flight. Later, in 1914, Glenn Curtiss heavily changed Langley's Aerodrome and flew it. The Smithsonian Institution at first claimed it was the first machine "capable of flight," but later changed that statement in 1928.

Richard Pearse's Pioneering Flights

Richard Pearse was a farmer and inventor from New Zealand. Many years later, witnesses said they saw Pearse fly and land a powered airplane on March 31, 1903. This was before the Wright brothers' famous flight.

The Wright Brothers: First in Flight

The Wright brothers, Orville and Wilbur, were brilliant inventors who solved the biggest problems of flight: control and power. They figured out how to control an aircraft's roll (tilting side-to-side) by twisting the wings, a method called wing warping. They also combined this with a steerable rudder for yaw (turning left or right). For pitch (tilting up or down), they used an elevator at the front of the plane.

The Wrights did careful tests in their own wind tunnel and flew many full-size gliders. They not only built the first working powered airplane, the Wright Flyer, but also greatly improved the science of how airplanes are designed.

They focused on learning to control gliders first. From 1900 to 1902, they built and flew three gliders. Their first two gliders didn't work as well as they hoped, but they learned a lot from them.

To find answers, the Wrights built their own wind tunnel. They tested 200 different wing designs and used this knowledge to build their 1902 glider. This glider was the first manned flying machine that could be controlled in all three directions: pitch, roll, and yaw. They flew it hundreds of times, and it worked much better!

For their powered Flyer, the Wrights designed and built their own lightweight engine. They also created very efficient wooden propellers. Their goal was to fly safely, so the plane was designed for lower speeds and needed to take off into the wind.

On December 17, 1903, at Kill Devil Hills, North Carolina, the Wright brothers made history! Orville Wright made the first sustained, controlled, powered flight in their Wright Flyer, flying 120 feet in 12 seconds. Later that day, Wilbur Wright flew 852 feet in 59 seconds. This was the first time a human flew a heavier-than-air machine that was powered and fully controlled.

The Wrights kept improving their planes. In 1905, after an accident, they rebuilt their Flyer III with bigger controls and made it more stable. This Flyer III became the first truly practical aircraft, flying consistently and safely. On October 5, 1905, Wilbur flew 24 miles in just under 40 minutes!

Later, the Wrights changed their design, moving the elevator to the back, like most airplanes today.

By 1907, Scientific American magazine recognized the Wright brothers' advanced knowledge. They even created a trophy to encourage more development in flying machines.

Making Airplanes Practical

After the first powered flights, inventors worked hard to make airplanes practical for everyday use. This time, before World War I, is known as the pioneer era of aviation.

Better Engines for Flight

Making airplanes fly well depended a lot on making good engines. The Wrights built their own 12-horsepower engine. Most early engines weren't powerful or reliable enough, so improving engines was key to making better airplanes.

In Europe, the Antoinette 8V engine, designed by Léon Levavasseur, became very popular after 1906. It was a powerful 50-horsepower engine that helped many early planes fly.

The British Green C.4 engine, built in 1908, was also powerful at 52 horsepower and used in many successful early aircraft.

Other engine types were also developed, like the 28-horsepower Nieuport engine in 1910.

In 1909, radial engines became important. The Anzani engine, though only 25 horsepower, was light and used by Louis Blériot for his famous flight across the English Channel. The Gnome rotary engine, invented by the Seguin brothers, was even more revolutionary. In a rotary engine, the entire engine spins with the propeller, making it very lightweight and reliable. These engines changed aviation and were used for many years, including in military planes.

Other engine types, like the powerful 75-horsepower Mercedes D.I from 1913, also became popular.

Wing Designs and Efficiency

Designers debated whether biplanes (two wings) or monoplanes (one wing) were better. Both types were still being built when World War I started in 1914.

The Antoinette Monobloc of 1911 was an early monoplane with a closed cockpit, but its engine wasn't powerful enough to fly well. More successful was the Deperdussin monoplane, which won the first Schneider Trophy race in 1913, flying at an average speed of 73.63 mph.

Inventors also tried triplanes (three wings) and even quadruplanes (four wings). Horatio Phillips experimented with multiplanes (many thin wings), but found they didn't work very well.

Other unique wing designs were tried, like the cellular wings by Alexander Graham Bell, but many of these didn't work efficiently.

Many of these early ideas, though not successful at first, later reappeared in different aircraft designs.

Improving Stability and Control

Early inventors focused on making planes stable, but not always controllable. The Wrights focused on control, even if it meant less stability. A good airplane needs both! Ailerons (movable parts on wings) slowly replaced wing warping for side-to-side control. Also, planes started to have fixed tails with movable parts, and propellers moved to the front of the aircraft.

In France, progress was quite fast.

On October 23 and November 12, 1906, Alberto Santos-Dumont made public flights in France with his 14-bis airplane. It was a biplane with a box-like wing and a front-mounted "boxkite" that acted as both elevator and rudder. His flight was the first officially confirmed flight of more than 25 meters, and he later set a world record by flying 220 meters in 21.5 seconds. He later added small ailerons to improve control.

In 1907, Louis Blériot flew the Blériot VII, a monoplane with modern controls. His Blériot VIII in 1908 was the first plane to have all the main parts of a modern flight control system. By 1909, his Blériot XI famously crossed the English Channel! Also in 1907, Henri Farman flew the Voisin biplane and won a big prize in 1908 for completing a 1-kilometer circular flight.

Léon Levavasseur's Antoinette IV in 1908 was a monoplane with a conventional tail and ailerons. However, the ailerons weren't very effective at first.

Henri Farman built his own improved airplane, the Farman III, which became very popular from 1909 to 1911. In Britain, Samuel Cody flew an aircraft similar to the Wright Flyer in 1908. In the USA, Glenn Curtiss made the first naval deck landing and takeoff in 1910. The Wright brothers also continued to improve their designs, eventually creating the two-seat Model B in 1910.

Many other unique designs were tested. J. W. Dunne in the UK developed stable tailless biplanes, like the D.5 in 1910. His designs were very stable, but not widely used because they weren't maneuverable enough for military use.

Airplanes on Water: Seaplanes

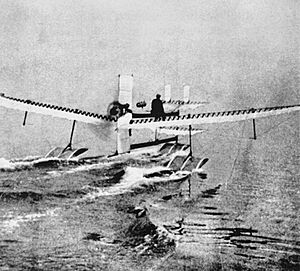

In 1901, Wilhelm Kress tried to fly his Drachenflieger, a floatplane with aluminum pontoons, but it didn't have enough power.

In 1910, Henri Fabre made the first seaplane flight in France with his Hydravion. It was an airplane with floats instead of wheels, allowing it to take off and land on water.

In 1912, the French Navy's ship Foudre became the world's first seaplane carrier, carrying a Voisin Canard floatplane.

Early seaplanes had trouble taking off because water would stick to the bottom. British designer John Cyril Porte solved this by adding a "step" to the bottom of the plane, which helped it lift off the water.

Airplanes in War

In 1909, airplanes were still fragile and not very powerful. They were often made of wood, steel wires, and fabric. Because they needed to be light, they could break apart easily, especially during sharp turns or dives.

Even so, people realized that airplanes could become important tools in war. In 1909, an Italian officer named Giulio Douhet said that the sky would become a new battlefield.

In 1911, Captain Bertram Dickson, the first British military officer to fly, predicted that airplanes would be used in battles and for scouting.

The first time objects were dropped from an airplane was when Paul W. Beck of the United States Army dropped sandbags (like practice bombs) over Los Angeles, California.

Airplanes were first used in war during the Italo-Turkish War in 1911–1912. On October 23, 1911, Captain Carlo Piazza flew a Blériot XI for scouting. On November 1, Giulio Gavotti dropped the first bombs from a plane. Captain Piazza also made the first photo-taking flight in March 1912.

Some planes from this time, like the Etrich Taube (1910) and the Sikorsky Ilya Muromets (1913), were even used in World War I. The Sikorsky Ilya Muromets was the first four-engine airplane and the biggest of its time.

Early Helicopters

The idea of using spinning rotors for vertical flight continued to be explored, separate from fixed-wing airplanes.

In the 1800s, many people worked on helicopter designs. In 1863, Gustave de Ponton d'Amécourt built a model with two rotors spinning in opposite directions. Enrico Forlanini's steam-powered model helicopter flew for 20 seconds in 1877, reaching 13 meters high!

Hiram Maxim also drew plans for a helicopter in 1872, but couldn't find a strong enough engine to build it.

In 1907, the French Gyroplane No. 1 made the first "tethered" (tied down) flight for a manned helicopter. It rose about 60 centimeters and hovered for a minute, but it was very wobbly.

Two months later, Paul Cornu made the first free flight in a manned helicopter, his Cornu helicopter, lifting 30 centimeters and staying in the air for 20 seconds.

See also

- Aviation accidents and incidents

- Aviation in the pioneer era (1903–1914)

- Aviation in World War I

- Claims to the first powered flight

- Timeline of aviation

| Bessie Coleman |

| Spann Watson |

| Jill E. Brown |

| Sherman W. White |