History of aviation facts for kids

The history of aviation is all about how humans learned to fly. It covers more than two thousand years! This journey started with simple things like kites. It moved on to people trying to jump from towers. Now, we have super-fast jets that fly faster than sound.

Kite flying began in China thousands of years ago. It slowly spread across the world. Kites are probably the first example of something man-made flying. Later, in the 1400s, Leonardo da Vinci dreamed of flying. He drew many designs for flying machines. But his ideas were not based on good science.

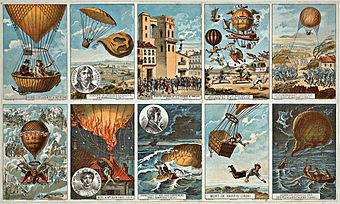

In the 1700s, hydrogen gas was discovered. This led to the invention of the hydrogen balloon. Around the same time, the Montgolfier brothers created the hot-air balloon. They soon started the first flights with people on board. Scientists like Sir George Cayley also studied how things move in the air. This led to the start of modern aerodynamics. Balloons were even used by armies from the late 1700s. The French government created special balloon groups during the French Revolution.

Later, people experimented with gliders. Otto Lilienthal was very important in this. By the early 1900s, engines got better. Also, people understood more about how air helps things fly. This made controlled, powered flight possible. The Wright brothers achieved this amazing feat. By 1909, the modern aeroplane with its tail was common. From then on, planes kept getting better with more powerful engines.

Giant airships, like the ones made by Ferdinand von Zeppelin, were the first big "ships of the air." They were called airships and ruled long-distance travel until the 1930s. Then, large flying boats became popular. After World War II, land planes took over from flying boats. The powerful new jet engine changed both air travel and military aviation forever.

In the late 1900s, digital electronics brought huge changes. Flight controls became much more advanced. "Fly-by-wire" systems meant computers helped control the plane. In the 2000s, pilotless drones became common. They are now used for military, civilian, and fun activities. Digital controls even made it possible to fly planes that are naturally unstable, like flying wings.

Contents

- Early Flying Machines: How It All Started

- Lighter Than Air: Balloons and Airships

- Heavier Than Air: The Rise of Airplanes

- The Pioneer Era (1903–1914): Planes Take Off

- World War I (1914–1918): Air Combat Begins

- Between the World Wars (1918–1939): Fast Changes

- World War II (1939–1945): Aviation Transforms Warfare

- Postwar Era (1945–1979): The Jet Age Begins

- Digital Age (1980–Present): Smart Planes and Drones

- 21st Century: New Challenges and Innovations

- See also

Early Flying Machines: How It All Started

Ancient Dreams of Flight

Since ancient times, people have dreamed of flying. There are many old stories about people trying to fly. They would strap on wings or cloaks. Then they would jump from high places, like towers. The Greek story of Daedalus and Icarus is one of the oldest. Similar stories come from ancient Asia and Europe. In these early days, people did not understand how to get lift or control a flying machine. Most attempts ended badly, with serious injuries or even death.

One story tells of Abbas ibn Firnas in the 800s AD. He supposedly jumped in Córdoba, Spain. He covered himself with vulture feathers and attached wings to his arms. A historian from the 1600s said Firnas flew some distance. But he landed with injuries. This was because he did not have a tail, which birds use to land. In the 1100s, a monk named Eilmer of Malmesbury also tried to fly. He attached wings to his hands and feet. He flew a short distance but broke both legs when landing. He also forgot to add a tail.

Many others tried similar jumps in the centuries that followed. As late as 1811, Albrecht Berblinger built a flying machine called an ornithopter. He jumped into the Danube River in Ulm.

Kites: The First Human-Made Flyers

The kite might be the first type of human-made aircraft. It was invented in China. This could have been as early as the 400s BC. Two people, Mozi and Lu Ban, are often given credit. Later kites often looked like flying insects or birds. Some even had strings and whistles to make music while flying. Old Chinese writings say kites were used for many things. They measured distances, tested the wind, lifted people, and sent messages.

Kites spread from China all over the world. When they reached India, the "fighter kite" was created. These kites had special lines to cut down other kites.

Kites That Carried People

Kites big enough to carry people were used a lot in ancient China. They were used for both everyday life and military purposes. Sometimes, they were even used as a punishment. One early flight was by a prisoner named Yuan Huangtou. He was a Chinese prince in the 500s AD. Stories of man-carrying kites also come from Japan. Kites arrived there from China around the 600s AD. It is said that at one time, there was a Japanese law against kites that carried people.

Rotor Wings: Spinning to the Sky

The idea of using a spinning "rotor" for vertical flight is very old. It started around 400 BC with the bamboo-copter. This was an ancient Chinese toy. A similar toy, called a "moulinet à noix" (rotor on a nut), appeared in Europe in the 1300s AD.

Hot Air Balloons: Floating Upwards

Since ancient times, the Chinese knew that hot air rises. They used this idea to make small hot air balloons called sky lanterns. A sky lantern is a paper balloon with a small lamp inside or underneath. People traditionally launch them for fun and during festivals. Some say these lanterns were known in China from the 200s BC. A general named Zhuge Liang (180–234 AD) is said to have used them in battle. He used them to scare enemy troops.

There is also some evidence that the Chinese "solved the problem of aerial navigation" with balloons. This was hundreds of years before the 1700s.

The Renaissance: New Ideas for Flight

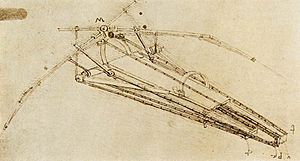

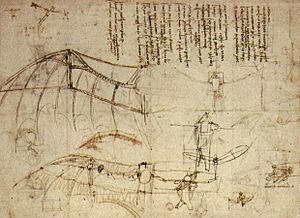

After Ibn Firnas's attempt, some thinkers started to figure out the basics of aircraft design. The most famous was Leonardo da Vinci. But his work was not known until 1797. So, it did not affect flying for a long time. His designs were logical, but not truly scientific. He thought that flying machines would not need much power. He based his designs on birds flapping their wings. He did not think about engine-powered propellers.

Leonardo studied how birds and bats fly. He thought bats were better because their wings had no holes. He looked at these animals and understood many ideas of aerodynamics. He knew that "An object offers as much resistance to the air as the air does to the object." This is similar to Isaac Newton's third law of motion, which came out much later in 1687.

From the late 1400s to 1505, Leonardo drew many designs for flying machines. These included ornithopters (flapping wing machines), gliders, and helicopters. He also drew parachutes and a wind speed gauge. His first designs were powered by humans. But he soon realized this would not work. Later, he focused on controlled gliding. He even sketched some designs powered by a spring.

In an essay called Sul volo (On flight), Leonardo described a flying machine. He called it "the bird." He built it from stiff linen, leather, and silk straps. In one of his notebooks, he wrote, "Tomorrow morning, on the second day of January, 1496, I will make the thong and the attempt." A popular, but likely fictional, story says that in 1505, Leonardo or one of his students tried to fly from Monte Ceceri.

Lighter Than Air: Balloons and Airships

Early Modern Theories

In 1670, Francesco Lana de Terzi wrote about lighter-than-air flight. He suggested using copper spheres with no air inside. These would be lighter than the air around them and could lift an airship. This idea was good in theory. But his design would not work. The air pressure outside would crush the spheres. Using a vacuum for lift is still not possible with today's materials.

In 1709, Bartolomeu de Gusmão asked the King of Portugal for help. He wanted support for his airship invention. He was very confident in it. A public test was planned for June 24, 1709, but it did not happen. However, reports say Gusmão did some smaller tests. He launched a ball to the roof using fire in 1709.

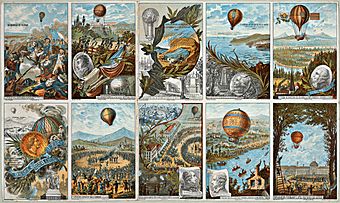

Balloons Take Flight

The year 1783 was a huge year for balloons and aviation. Between June and December, five amazing "firsts" happened in France:

- On June 4, the Montgolfier brothers showed off their unmanned hot air balloon.

- On August 27, Jacques Charles and the Robert brothers launched the world's first unmanned hydrogen balloon.

- On October 19, the Montgolfiers launched the first manned flight. This was a balloon tied to the ground with people inside.

- On November 21, the Montgolfiers launched the first free flight with people. Jean-François Pilâtre de Rozier and the Marquis François d'Arlandes flew about 8 kilometers (5 miles). Their balloon was powered by a wood fire.

- On December 1, Jacques Charles and Nicolas-Louis Robert launched their manned hydrogen balloon. A huge crowd watched. They went up about 550 meters (1,800 feet). They landed after flying 36 kilometers (22 miles) for over two hours. Charles then went up alone. He went very high, about 3,000 meters (9,800 feet). He felt pain in his ears and never flew again.

Ballooning became very popular in Europe in the late 1700s. It helped people understand how altitude affects the atmosphere.

Balloons that could not be steered were used during the American Civil War. The Union Army Balloon Corps used them. A young Ferdinand von Zeppelin first flew as a balloon passenger with the Union Army in 1863.

In the early 1900s, ballooning was a popular sport in Britain. These balloons often used coal gas for lift. It was not as strong as hydrogen. But coal gas was much easier to find.

Airships: Steerable Balloons

Airships were first called "dirigible balloons." This means "steerable balloons." People still sometimes call them dirigibles today.

Work to make steerable balloons continued through the 1800s. The first powered, controlled, and sustained flight of a lighter-than-air craft happened in 1852. Henri Giffard flew 15 miles (24 km) in France. His craft was powered by a steam engine.

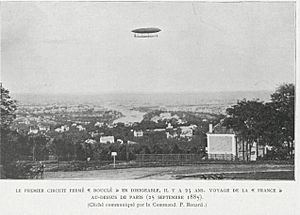

Another big step happened in 1884. The French Army airship, La France, made the first fully controllable free flight. Charles Renard and Arthur Krebs flew it. The airship was 52 meters (170 feet) long. It flew 8 kilometers (5 miles) in 23 minutes. It used an 8½ horsepower electric motor.

However, these early airships were often weak and did not last long. Regular, controlled flights only became possible with the invention of the internal combustion engine.

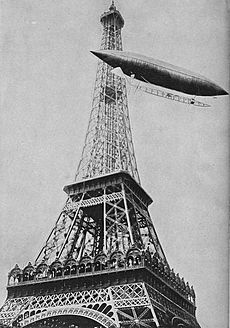

The first aircraft to make regular controlled flights were non-rigid airships, also called "blimps." The most successful early pilot was Alberto Santos-Dumont from Brazil. He combined a balloon with an internal combustion engine. On October 19, 1901, he flew his airship Number 6 over Paris. He flew around the Eiffel Tower and back in under 30 minutes. He won a prize for this flight. Santos-Dumont designed and built several aircraft.

At the same time, the first successful rigid airships were being made. These could carry much more cargo than planes for many decades. Rigid airship design was led by the German count Ferdinand von Zeppelin.

The first Zeppelin airship was built starting in 1899. It was built in a floating hall on Lake Constance. This made it easier to start flights by lining up with the wind. The first Zeppelin, LZ 1, was 128 meters (420 feet) long. It had two Daimler engines.

Its first flight on July 2, 1900, lasted only 18 minutes. It had to land because a part broke. After repairs, it showed its potential. But it could not get enough investors. It took several years for Count Zeppelin to raise money for another try.

German airship passenger service, called DELAG, started in 1910.

Airships were used in both World War I and II. They are still used a little today. But their development has been mostly overshadowed by planes.

Heavier Than Air: The Rise of Airplanes

Early Attempts and Scientific Study

In 1647, Italian inventor Tito Livio Burattini built a model aircraft. It had four fixed glider wings. It was said to have lifted a cat in 1648. But it could not lift Burattini himself. His "Dragon Volant" is seen as a very complex plane built before the 1800s.

The first paper about aviation was by Emanuel Swedenborg in 1716. He described a flying machine. He knew it would not fly, but he saw it as a start. He believed the problem would be solved. He wrote that it needed more force and less weight than a human body. He thought a strong spring might help. He also warned that early attempts might lead to injuries. Swedenborg was right that powering an aircraft was a key problem.

On May 16, 1793, Spanish inventor Diego Marín Aguilera flew 300–400 meters (980–1,300 feet). He used a flying machine to cross a river.

In 1801, French officer André Guillaume Resnier de Goué glided 300 meters (980 feet). He started from city walls and broke only one leg. In 1837, French general fr:Isidore Didion said that aviation would only work with a powerful engine. It needed an engine much stronger than steam machines or human strength.

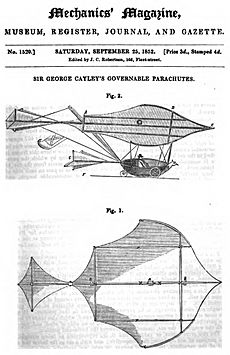

Sir George Cayley: The Father of the Aeroplane

Sir George Cayley was first called the "father of the aeroplane" in 1846. He began the first serious study of the physics of flight. He later designed the first modern heavier-than-air craft. His most important contributions include:

- Explaining the ideas and rules of heavier-than-air flight.

- Understanding how birds fly, scientifically.

- Doing scientific tests to show drag and how to make things smooth. He also showed how curving a wing creates more lift.

- Defining the modern aeroplane. It has a fixed wing, a body (fuselage), and a tail.

- Showing how manned gliders could fly.

- Explaining the importance of power-to-weight ratio for flight.

Cayley's first big idea was to study lift scientifically. He used a spinning arm to test small models. He did not try to fly a whole plane model at first.

In 1799, he described the idea of the modern aeroplane. It was a fixed-wing machine with separate parts for lift, propulsion, and control.

In 1804, Cayley built a model glider. It was the first modern heavier-than-air flying machine. It looked like today's planes. It had an angled wing at the front and an adjustable tail at the back.

In 1809, he started publishing an important three-part paper. It was called "On Aerial Navigation." In it, he wrote the first scientific statement of the problem: "The whole problem is confined within these limits, viz. to make a surface support a given weight by the application of power to the resistance of air." He named the four forces that affect an aircraft: thrust, lift, drag, and weight. He also explained stability and control in his designs. He described the importance of the curved aerofoil (wing shape), dihedral (wing angle), and reducing drag. He also helped understand and design ornithopters and parachutes.

In 1848, he built a triplane glider. It was big and safe enough to carry a child. A local boy flew in it, but his name is not known.

In 1852, he published a design for a full-size manned glider. He called it a "governable parachute." In 1853, he built a version that could launch from a hill. It carried the first adult aviator across Brompton Dale.

His smaller inventions included the rubber-powered motor. This was a good power source for research models. By 1808, he even re-invented the wheel. He designed the tension-spoked wheel. This made the landing gear much lighter.

The Age of Steam-Powered Flight

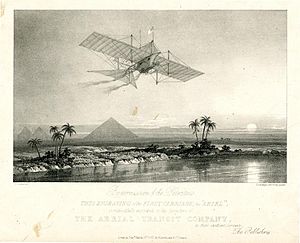

Based on Cayley's work, Henson designed an aerial steam carriage in 1842. It was only a design, but it was the first ever for a propeller-driven fixed-wing plane.

In 1866, the Aeronautical Society of Great Britain was founded. Two years later, the first air show was held in London. John Stringfellow won a prize for the best steam engine. In 1848, Stringfellow made the first powered flight. It was an unmanned steam-powered monoplane. It flew ten feet indoors before crashing. A second try was better. The machine flew freely for thirty yards. Francis Herbert Wenham also studied curved wings. He made important discoveries. To test his ideas, he built several gliders from 1858. Some were manned, some unmanned. He realized that long, thin wings are better than bat-like ones. This is now called the aspect ratio of a wing.

The late 1800s was a time of intense study. Many "gentleman scientists" did most of the research. One was Matthew Piers Watt Boulton. He studied how to control flight sideways. He was the first to patent an aileron control system in 1868.

In 1871, Wenham built the first wind tunnel. He used a fan to blow air over models.

French researchers were also busy. In 1857, Félix du Temple proposed a monoplane. It had a tail and landing gear that could be pulled in. He built a model powered by clockwork, then steam. In 1874, he made a short hop with a full-size manned craft. It took off on its own from a ramp. It glided for a short time and landed safely. This was the first successful powered glide.

In 1865, Louis Pierre Mouillard published an important book called The Empire Of The Air.

In 1856, Frenchman Jean-Marie Le Bris made the first flight higher than his starting point. His glider, "L'Albatros artificiel", was pulled by a horse on a beach. He reportedly reached 100 meters (330 feet) high and flew 200 meters (660 feet).

Alphonse Pénaud from France improved ideas about wing shapes and aerodynamics. He built successful models of planes, helicopters, and ornithopters. In 1871, he flew the first stable fixed-wing plane. It was a model monoplane called the "Planophore." It flew 40 meters (130 feet). Pénaud's model used many of Cayley's ideas. These included a tail, angled wings for stability, and rubber power. The Planophore also had good stability from front to back. This was a new and important idea. Pénaud's later design for a plane that could land on water or land was never built. But it had other modern features. It was a tailless monoplane with a single fin and two propellers. It also had moving tail surfaces, retractable landing gear, and a closed cockpit with instruments.

Victor Tatin, another Frenchman, was also a great theorist. In 1879, he flew a model. It was a monoplane with two propellers and a separate horizontal tail. It was powered by compressed air. This was the first model to take off on its own power while tied to a pole.

In 1884, Alexandre Goupil published his work Aerial Locomotion. But the flying machine he built later did not fly.

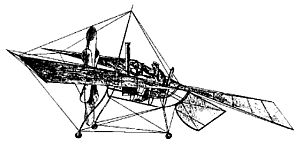

In 1890, French engineer Clément Ader finished his first steam-powered flying machine, the Éole. On October 9, 1890, Ader made an uncontrolled hop of about 50 meters (160 feet). This was the first manned plane to take off on its own power. His Avion III from 1897 had two steam engines but failed to fly. Ader later claimed it was successful. But this was disproven in 1910.

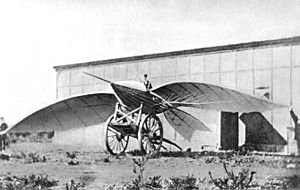

Sir Hiram Maxim was an American engineer in England. He built his own test equipment. He constructed a large machine with a 32-meter (105-foot) wingspan. It was 44 meters (145 feet) long and had a crew of three. Two propellers were powered by two steam engines. Each engine made 180 horsepower. The machine weighed 3,600 kg (8,000 lb). It was meant to test lift. It ran on rails and had upper rails to hold it down. In 1894, on its third run, it broke free. It flew about 180 meters (200 yards) at a height of 0.6 to 0.9 meters (two to three feet). It was badly damaged when it fell. Maxim stopped his experiments soon after.

Learning to Glide: Otto Lilienthal and Human Flight

In the late 1800s, many important people were working on the modern aeroplane. Without a good engine, they focused on making gliders stable and controllable. In 1879, Biot built a bird-like glider with Massia. He flew in it briefly. It is now in a museum in France. It is said to be the oldest human-carrying flying machine still existing.

The Englishman Horatio Phillips made important contributions to aerodynamics. He did many wind tunnel tests on wing shapes. He proved the ideas of lift that Cayley and Wenham had. His findings are still used in modern wing design. Between 1883 and 1886, American John Joseph Montgomery built three manned gliders. He also studied aerodynamics and lift on his own.

Otto Lilienthal became known as the "Glider King" of Germany. He built on Wenham's work. In 1889, he published his research in a book. It is seen as one of the most important works in aviation history. He also made many hang gliders. These included bat-wing, monoplane, and biplane designs. His "Normal soaring apparatus" was the first airplane made in large numbers. His company was the first airplane production company in the world.

Starting in 1891, he was the first person to make controlled, untethered glides regularly. He was also the first to be photographed flying a heavier-than-air machine. This sparked interest around the world. Lilienthal's work led to the idea of the modern wing. His flights in 1891 are seen as the start of human flight. Because of this, he is often called the "father of aviation."

He carefully wrote down and photographed his work. This is why he is one of the best-known early pioneers. Lilienthal made over 2,000 glides. He died in 1896 from injuries in a glider crash.

Octave Chanute continued Lilienthal's work. He designed aircraft after retiring early. He paid for the development of several gliders. In 1896, his team flew several designs. They decided a biplane design was best. Like Lilienthal, he documented his work with photos.

In Britain, Percy Pilcher built and flew several gliders in the mid to late 1890s.

The invention of the box kite by Australian Lawrence Hargrave led to the practical biplane. In 1894, Hargrave linked four of his kites. He added a seat and was the first to get lift with a heavier-than-air craft. He flew up 5 meters (16 feet). Later pioneers of manned kite flying included Samuel Franklin Cody in England.

Early Powered Flight Attempts

William Frost's Glider

William Frost from Wales started his project in 1880. After 16 years, he designed a flying machine. In 1894, he got a patent for a "Frost Aircraft Glider." Witnesses said the craft flew in 1896. It traveled 460 meters (500 yards) before hitting a tree.

Samuel Pierpont Langley's Aerodromes

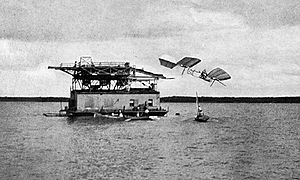

Samuel Pierpont Langley began studying aerodynamics seriously. In 1891, he published his research. He wanted his planes to be stable on their own. So, he did not focus much on in-flight control. On May 6, 1896, Langley's Aerodrome No. 5 made the first successful flight of a large, unpiloted, engine-driven heavier-than-air craft. It launched from a catapult on a houseboat. It flew 1,005 meters (3,300 feet) and then 700 meters (2,300 feet). It flew at about 40 km/h (25 mph). Both times, it landed in the water as planned. It had no landing gear to save weight. On November 28, 1896, Aerodrome No. 6 flew 1,460 meters (4,800 feet). Alexander Graham Bell saw and photographed this flight.

With these successes, Langley sought money to build a full-size plane for a person. The U.S. government gave him $50,000. He planned to build the Aerodrome A. He started with a smaller version, the Quarter-scale Aerodrome. It flew twice in 1901 and again in 1903 with a new engine.

He then needed a good engine. He hired Stephen Balzer, but the engine was not powerful enough. Langley's assistant, Charles M. Manly, redesigned it. It became a powerful 52-horsepower engine. This was a huge achievement for the time. With both power and a design, Langley had high hopes.

But the plane was too weak. Scaling up the small models made it too fragile. Two launches in late 1903 ended with the Aerodrome crashing into the water. The pilot, Manly, was rescued each time. The control system was also not good enough. It had no way to control side-to-side movement.

Langley could not get more money. His efforts ended. Nine days after his last crash, on December 17, the Wright brothers successfully flew their Flyer.

Gustave Whitehead's Claim

Gustave Weißkopf was a German who moved to the U.S. He changed his name to Whitehead. From 1897 to 1915, he built flying machines and engines. On August 14, 1901, he claimed to have made a controlled, powered flight. This was two and a half years before the Wright Brothers. He said he flew his Number 21 monoplane in Connecticut. A local newspaper reported it. Years later, some people said they saw his flights.

In 2013, Jane's All the World's Aircraft, an important aviation source, said Whitehead's flight was the first. But the Smithsonian Institution and many historians still say the Wrights were first.

Richard Pearse's Experiments

Richard Pearse was a farmer and inventor in New Zealand. Witnesses interviewed years later said Pearse flew a powered machine on March 31, 1903. This was nine months before the Wright brothers. But the evidence is debated. Pearse himself never claimed this. In 1909, he said he did not try anything practical until 1904. If he did fly in 1903, his flight was not as well controlled as the Wrights'.

The Wright Brothers: First to Fly Successfully

The Wright brothers used a careful method. They focused on controlling the aircraft. From 1898 to 1902, they built and tested many kites and gliders. Their gliders worked, but not as well as they expected. Their first full-size glider in 1900 had only half the lift they thought it would. Their second glider in 1901 was even worse. Instead of giving up, the Wrights built their own wind tunnel. They created devices to measure lift and drag on 200 wing designs. This helped them fix mistakes in their calculations. Their tests led to a third glider in 1902. It had a better wing shape and true three-axis control. They flew it hundreds of times successfully. By using careful experiments, the Wrights built a working aircraft. They also helped advance the science of aeronautical engineering.

The Wrights were likely the first to seriously try to solve both the power and control problems at once. Both were hard, but they kept going. They solved the control problem by inventing wing warping. This helped them control the roll (side-to-side movement). They combined this with a steerable rear rudder for yaw (nose left/right) control. They also designed and built a low-powered engine. They carved wooden propellers that were more efficient than any before. This allowed them to fly well with little engine power. Wing warping was used only for a short time. But combining side control with a rudder was a key step in aircraft control. Many early flyers took big risks. But the Wrights focused on safety. They wanted to learn to fly without too much danger. This focus, and their low engine power, meant they flew slowly and took off into the wind.

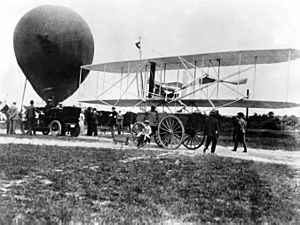

According to the Smithsonian Institution and Fédération Aéronautique Internationale (FAI), the Wrights made the first sustained, controlled, powered flight with a person. This happened at Kill Devil Hills, North Carolina, on December 17, 1903.

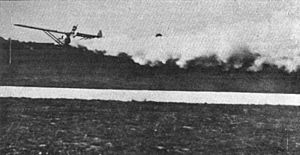

The first flight by Orville Wright was 37 meters (120 feet) in 12 seconds. A famous photo captured it. In the fourth flight that day, Wilbur Wright flew 260 meters (852 feet) in 59 seconds. Three coastal rescue workers, a local businessman, and a boy saw the flights. This made them the first public and well-documented flights.

Orville described the last flight: "The first few hundred feet were up and down... but by the time three hundred feet had been covered, the machine was under much better control." He said the plane pitched again at 800 feet and hit the ground. The front rudder was broken, but the main part was fine. They thought they could fix it in a day or two. They flew only about 3 meters (10 feet) high for safety. So, they had little room to move. All four flights in the windy conditions ended with a bumpy landing. Experts later said the 1903 Wright Flyer was very unstable. Only the Wrights, who trained on their 1902 glider, could manage it.

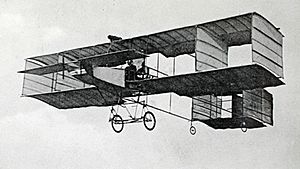

The Wrights kept flying at Huffman Prairie in Ohio in 1904–05. In May 1904, they introduced the Flyer II. It was heavier and better. On June 23, 1905, they first flew the Flyer III. After a bad crash in July 1905, they rebuilt it. They made big changes. They almost doubled the size of the elevator and rudder. They moved them farther from the wings. They added two fixed vertical fins. They also gave the wings a slight dihedral (upward angle). They separated the rudder from the wing-warping control. This is how it is on all future planes. When they flew again, the results were immediate. The serious pitching problem was greatly reduced. Crashes stopped. Flights with the redesigned Flyer III started lasting over 10 minutes, then 20, then 30. The Flyer III became the first practical aircraft. It flew consistently under full control. It brought its pilot back safely and landed without damage. On October 5, 1905, Wilbur flew 39 km (24 miles) in 39 minutes and 23 seconds.

In April 1907, Scientific American magazine said the Wright brothers had the most advanced knowledge of flight. But the magazine also said no public flight had been made in the U.S. before that issue. So, they created a trophy to encourage airplane development.

The Pioneer Era (1903–1914): Planes Take Off

This time saw the development of practical planes and airships. They were used for fun, sports, and by the military.

European Pioneers Join the Race

The Wright Brothers' flight control system was published in 1906. But its importance was not fully understood. European experimenters often tried to make planes that were stable on their own.

Short powered flights happened in France. Romanian engineer Traian Vuia flew 12 and 24 meters in 1906. His plane had wheels. Then Jacob Ellehammer built a monoplane. He tested it in Denmark in 1906, flying 42 meters.

On September 13, 1906, Alberto Santos-Dumont from Brazil made a public flight in Paris. He flew the 14-bis, or Oiseau de proie (bird of prey). It had a canard (front wing) and angled wings. It flew 60 meters (200 feet) in front of a large crowd. This was the first flight in Europe confirmed by the Aéro-Club de France. He won a prize for flying over 25 meters. On November 12, 1906, Santos-Dumont set the first world record. He flew 220 meters (720 feet) in 21.5 seconds. The 14-bis only made one more short flight in March 1907.

In March 1907, Gabriel Voisin flew his Voisin biplane. On January 13, 1908, Henri Farman flew a Voisin biplane. He won a prize for flying over a kilometer and landing where he took off. The flight lasted 1 minute and 28 seconds.

Flight Becomes a Real Technology

Santos-Dumont later added ailerons (small flaps on wings) to his planes. This helped with side-to-side stability. His final design, first flown in 1907, was the Demoiselle monoplane series. The Demoiselle No 19 could be built in just 15 days. It became the world's first mass-produced aircraft. The Demoiselle reached 120 km/h (75 mph). It had a simple body made of bamboo. The pilot sat between the main wheels. It was controlled by a tail that moved like a universal joint. Roll control came from wing warping.

In 1908, Wilbur Wright went to Europe. Starting in August, he gave flight shows in France. His first show on August 8 amazed French aviation experts. They were shocked by how much better the Wrights' plane was. Especially its ability to make sharp, controlled turns. Almost all European experimenters then understood the importance of roll control for turns. Henri Farman added ailerons to his biplane. Soon after, he started his own aircraft company. His first plane was the important Farman III biplane.

The next year, powered flight was widely accepted. It was no longer just for dreamers. On July 25, 1909, Louis Blériot became famous. He won a £1,000 prize for flying across the English Channel. In August, about half a million people watched one of the first air meetings. It was the Grande Semaine d'Aviation in Reims.

In 1914, Tony Jannus piloted the first flight of the St. Petersburg-Tampa Airboat Line. This was the world's first commercial passenger airline.

Historians debate if the Wright brothers patent war slowed down aviation in the U.S. compared to Europe. The patent war ended during World War I. The government pushed the industry to share patents.

Rotorcraft: The First Helicopters

In 1877, Enrico Forlanini built an unmanned helicopter. It was powered by a steam engine. It rose 13 meters (43 feet) high and stayed there for 20 seconds.

The first time a manned helicopter lifted off the ground was in 1907. It was a tied flight by the Breguet-Richet Gyroplane. Later that year, the Cornu helicopter from France made the first free flight. But these were not practical designs.

Military Use of Airplanes

Almost as soon as planes were invented, armies used them. Italy was the first country to use them in war. Their planes did scouting, bombing, and helped aim artillery in Libya. This was during the Italian-Turkish war (1911–1912). The first scouting mission was on October 23, 1911. The first bombing was on November 1, 1911. Then Bulgaria used planes in the First Balkan War (1912–13). They attacked and scouted Ottoman positions. World War I was the first war to see planes used a lot for attacking, defending, and scouting. Both the Allies and Central Powers used planes and airships widely.

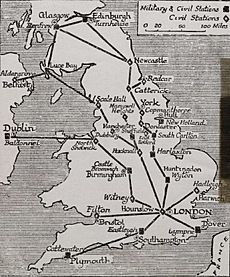

Before World War I, people did not think planes would be good weapons. But they knew planes could take photos. All major European armies had light planes. These were usually based on sports planes. They were used for reconnaissance (scouting). Radiotelephones were also being tested on planes. This was for pilots to talk to commanders on the ground.

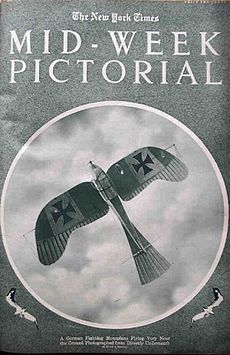

World War I (1914–1918): Air Combat Begins

Soon, planes started shooting at each other. But it was hard to aim a gun from a plane. The French solved this in late 1914. Roland Garros put a fixed machine gun on the front of his plane. Adolphe Pegoud became the first "flying ace" with five victories. But he was also the first ace to die in action. German pilot Kurt Wintgens made the first aerial victory on July 1, 1915. He used a purpose-built fighter plane with a synchronized machine gun. This allowed him to shoot through the propeller.

Pilots became like modern knights. They fought individual battles in the sky. Many pilots became famous for air-to-air combat. The most well-known was Manfred von Richthofen, the "Red Baron." He shot down 80 planes. He flew several different planes, including the famous Fokker Dr.I. On the Allied side, René Paul Fonck is credited with 75 victories.

France, Britain, Germany, and Italy made most of the fighter planes in the war. German aviation expert Hugo Junkers showed the future. He started using all-metal aircraft from late 1915.

Between the World Wars (1918–1939): Fast Changes

The years between World War I and World War II saw huge progress in aircraft technology. Planes changed from slow biplanes made of wood and fabric. They became sleek, fast monoplanes made of aluminum. This was thanks to the work of Hugo Junkers. The age of big rigid airships ended. The first successful rotorcraft appeared. This was the autogyro, invented by Spanish engineer Juan de la Cierva in 1919. In this design, the rotor spins like a windmill. A separate engine pushes the aircraft forward.

After World War I, experienced fighter pilots wanted to show their skills. Many American pilots became barnstormers. They flew into small towns, showing off their flying and giving rides. Later, barnstormers formed organized shows. Air shows started with races, stunts, and flying feats. Air races pushed engine and plane design forward. The Schneider Trophy races led to faster and sleeker monoplanes. Pilots competed for money, so they wanted to go faster. Amelia Earhart was a famous barnstormer and air show pilot. She was the first female pilot to cross the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans.

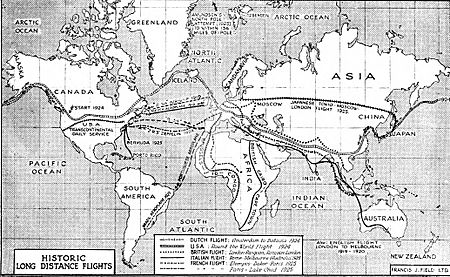

Other prizes for distance and speed also helped development. On June 14, 1919, Captain John Alcock and Lieutenant Arthur Brown flew a Vickers Vimy non-stop. They flew from Newfoundland to Ireland. They won a £13,000 prize. The first flight across the South Atlantic was in 1922. Naval pilots Gago Coutinho and Sacadura Cabral flew from Lisbon to Rio de Janeiro. They used special navigation tools. Five years later, Charles Lindbergh won $25,000. He made the first solo non-stop flight across the Atlantic. This caused a "Lindbergh boom" in aviation. Air mail increased, pilot license applications tripled, and planes quadrupled in six months.

Australian Sir Charles Kingsford Smith was the first to fly across the larger Pacific Ocean. He and his crew flew the Southern Cross from California to Australia in three parts. The first part was 3,860 km (2,400 miles) to Hawaii. The second was 5,000 km (3,100 miles) to Fiji. This was the hardest part, through a big lightning storm. Then they flew to Brisbane, Australia. They landed on June 9, 1928, after flying about 11,900 km (7,400 miles). A huge crowd met Kingsford Smith. With Charles Ulm, Kingsford Smith later became the first to fly around the world in 1929.

The first lighter-than-air crossings of the Atlantic were by airship in July 1919. His Majesty's Airship R34 flew from Scotland to New York and back. By 1929, airship technology was advanced. The Graf Zeppelin completed the first round-the-world flight. In October, it started the first commercial transatlantic service. However, the age of rigid airships ended after the Hindenburg caught fire. This happened on May 6, 1937, killing 35 people. Other airship accidents had already raised doubts about their safety. After the Hindenburg disaster, the remaining airship, the Graf Zeppelin, was retired. Its replacement, the Graf Zeppelin II, flew from 1938 to 1939. But it was grounded when Germany started World War II. Both German zeppelins were scrapped in 1940 for metal. The last American rigid airship was taken apart in 1939.

Meanwhile, Germany was limited in building planes by the Treaty of Versailles. So, they developed gliding as a sport in the 1920s. Today, over 400,000 people participate in sailplane aviation.

Fritz von Opel helped make rockets popular for vehicles and planes. In the 1920s, he started the first rocket program, Opel-RAK. This led to speed records for cars and trains. It also led to the first manned rocket-powered flight in September 1929. Opel and others built the world's first rocket glider. In 1928, one of his rocket cars, the Opel RAK2, reached 238 km/h (148 mph). Many people watched this event. A world record for trains was set with RAK3 at 256 km/h (159 mph). After these successes, von Opel piloted the first public rocket-powered flight. He used a special Opel RAK.1 rocket plane.

News around the world reported on these efforts. The Great Depression ended the Opel-RAK program. But Max Valier continued the work. He died testing liquid-fuel rockets. He is seen as the first person to die in the early space age.

In 1929, Jimmy Doolittle developed instrument flight. This meant pilots could fly using only instruments, even in bad weather.

1929 also saw the first flight of the largest plane built until then: the Dornier Do X. It had a wingspan of 48 meters (157 feet). On one test flight, it carried 169 people. This record was not broken for 20 years.

Only five years after the Dornier Do-X, Tupolev designed the largest aircraft of the 1930s. It was the Maksim Gorky in the Soviet Union. It was built using Junkers' metal aircraft methods.

In the 1930s, the jet engine began to be developed in Germany and Britain. Both countries would have jet aircraft by the end of World War II.

Sabiha Gökçen became the first Turkish female aviator and the world's first female combat pilot. She flew fighter and bomber planes. During her career, she flew about 8,000 hours, including 32 combat missions.

World War II (1939–1945): Aviation Transforms Warfare

World War II greatly sped up the development and production of aircraft. New flight-based weapon systems were also created. Air combat tactics and strategies improved. Large-scale strategic bombing campaigns were launched. Fighter escorts were introduced. More flexible planes and weapons allowed precise attacks. These included dive bombers, fighter-bombers, and ground-attack aircraft. New technologies like radar also helped coordinate air defense.

The first jet aircraft to fly was the Heinkel He 178 (Germany) in 1939. Then came the world's first operational jet aircraft, the Me 262, in July 1942. The world's first jet-powered bomber, the Arado Ar 234, flew in June 1943. British jets, like the Gloster Meteor, came later. But they saw only brief use in World War II. Germany also developed the first cruise missile (V-1) and the first ballistic missile (V-2). They also made the first (and only) operational rocket-powered combat plane, the Messerschmitt Me 163. It reached speeds of up to 1,130 km/h (700 mph). The first vertical take-off interceptor, the Bachem Ba 349 Natter, was also German. However, jet and rocket planes had limited impact. This was because they were introduced late in the war. Germany also faced fuel shortages and lacked experienced pilots.

Helicopters also developed quickly in World War II. The Focke Achgelis Fa 223 and the Flettner Fl 282 synchropter appeared in Germany in 1941. The Sikorsky R-4 appeared in the USA in 1942.

Postwar Era (1945–1979): The Jet Age Begins

After World War II, commercial aviation grew fast. It mostly used old military planes to carry people and cargo. This growth was helped by many leftover bomber planes. These could be changed into commercial aircraft. The DC-3 also made commercial flights easier and longer. The first commercial jet airliner to fly was the British de Havilland Comet. By 1952, BOAC used the Comet for regular flights. It was a great technical achievement. But the plane had several public failures. The shape of the windows caused cracks due to metal fatigue. This led to the plane's body breaking apart. By the time problems were fixed, other jet airliners were already flying.

The USSR's Aeroflot was the first airline to have regular jet services. This started on September 15, 1956, with the Tupolev Tu-104. The Boeing 707 and DC-8 brought new levels of comfort and safety. They started the age of mass commercial air travel, called the Jet Age.

In October 1947, Chuck Yeager flew the rocket-powered Bell X-1 faster than the sound barrier. Some fighter pilots might have done this during the war. But this was the first controlled, level flight to break the sound barrier. More distance records fell in 1948 and 1952. These included the first jet crossing of the Atlantic. And the first nonstop flight to Australia.

The invention of nuclear bombs in 1945 made military aircraft very important. This was during the Cold War. Even a small fleet of long-range bombers could attack the enemy. So, great efforts were made to develop defenses. At first, fast supersonic interceptor aircraft were made. By 1955, most efforts shifted to guided surface-to-air missiles. But then a new threat appeared: intercontinental ballistic missiles. These could not be stopped. Their possibility was shown in 1957. The Soviet Union launched Sputnik 1. This started the Space Race.

In 1961, the sky was no longer the limit for manned flight. Yuri Gagarin orbited the Earth in 108 minutes. He then used his capsule to safely reenter the atmosphere. The U.S. responded by launching Alan Shepard into space. In 1963, Canada became the third country to send a satellite into space. The space race between the U.S. and the Soviet Union led to men landing on the Moon in 1969.

In 1967, the X-15 set the air speed record for an aircraft. It flew at 7,300 km/h (4,534 mph), or Mach 6.1. Only vehicles designed for space have broken this record.

The Harrier jump jet first flew in 1969. It is a British military jet that can take off and land vertically. This was the same year Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin walked on the Moon. Also in 1969, Boeing showed the Boeing 747. And the Aérospatiale-BAC Concorde supersonic passenger airliner had its first flight. The Boeing 747 was the largest commercial passenger plane ever. It still carries millions of passengers. But the Airbus A380 is now bigger. In 1975, Aeroflot started regular service with the Tu-144. This was the first supersonic passenger plane. In 1976, British Airways and Air France started supersonic service across the Atlantic with Concorde. A few years earlier, the SR-71 Blackbird set a record. It crossed the Atlantic in under 2 hours. Concorde followed this path.

In 1979, the Gossamer Albatross became the first human-powered aircraft to cross the English Channel. This finally made the centuries-old dream of human flight come true.

Digital Age (1980–Present): Smart Planes and Drones

The last part of the 1900s saw a change in focus. There were no longer huge leaps in speed or distance. Instead, the digital revolution spread. It changed flight avionics (electronics) and how aircraft were designed and made.

In 1986, Dick Rutan and Jeana Yeager flew the Rutan Voyager. It flew around the world without refueling or landing. In 1999, Bertrand Piccard was the first person to circle the Earth in a balloon.

Digital fly-by-wire systems allow planes to be designed to be less stable. This makes military aircraft like the General Dynamics F-16 Fighting Falcon more agile. Now, it is also used to reduce drag on commercial airliners.

The U.S. Centennial of Flight Commission was set up in 1999. It encouraged celebrations for 100 years of powered flight. It promoted programs to teach people about aviation history.

21st Century: New Challenges and Innovations

In the 21st century, there is more interest in saving fuel. Also, in using different types of fuel. Low cost airlines and airports have grown. Many developing countries now have better access to air travel. But crowded airports are still a problem. Commercial aviation now serves about 20,000 city pairs. This is up from less than 10,000 in 1996.

There is new interest in supersonic flight. Demand for it dropped around 2000. This made flights unprofitable. The Concorde stopped flying due to low demand and rising costs.

In the early 2000s, digital technology changed military aviation. Pilots started to be replaced by remote operators. Or by fully autonomous unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs). In April 2001, the unmanned Global Hawk flew non-stop from the U.S. to Australia. This was the longest flight by an unmanned aircraft. It took 23 hours and 23 minutes. In October 2003, a computer-controlled model aircraft made the first fully autonomous flight across the Atlantic. UAVs are now a key part of modern warfare. They carry out precise attacks controlled by a remote operator.

Major disruptions to air travel in the 21st century include the closing of U.S. airspace after the September 11 attacks. Also, most European airspace closed after the 2010 eruption of Eyjafjallajökull (a volcano).

In 2015, André Borschberg and Bertrand Piccard flew a record distance. They flew 7,212 km (4,481 miles) from Japan to Hawaii. They used a solar-powered plane, Solar Impulse 2. The flight took almost five days. At night, the plane used its batteries and energy saved from the day.

On July 14, 2019, Frenchman Franky Zapata got world attention. He rode his jet-powered Flyboard Air in a parade. He then crossed the English Channel on his device on August 4, 2019. He covered 35 kilometers (22 miles) in 22 minutes. He made one stop to refuel.

July 24, 2019, was the busiest day in aviation. Flightradar24 recorded over 225,000 flights that day. This includes helicopters, private jets, gliders, and personal aircraft. The website has tracked flights since 2006.

On June 10, 2020, the Pipistrel Velis Electro became the first electric airplane. It received a special certificate from EASA.

In the early 21st century, the first fifth-generation military fighters were made. The F-22 Raptor was one of them. Today, Russia, America, and China have 5th generation aircraft.

The COVID-19 pandemic greatly affected the aviation industry. This was due to travel restrictions and less demand. It might also change the future of air travel. For example, wearing face masks on planes became common since 2020.

Mars: Flying on Another Planet

On April 19, 2021, NASA successfully flew an unmanned helicopter on Mars. This was humanity's first controlled powered flight on another planet. The Ingenuity helicopter rose 3 meters (10 feet) high. It hovered for 30 seconds. Its companion rover, Perseverance, filmed the flight. On April 22, 2021, Ingenuity made a second, more complex flight. As a tribute to all past aircraft, the Ingenuity helicopter carries a small piece of fabric. It is from the wing of the 1903 Wright Flyer.

|

See also

In Spanish: Historia de la aviación para niños

In Spanish: Historia de la aviación para niños

- Aviation archaeology

- Claims to the first powered flight

- List of firsts in aviation

- Timeline of aviation

| Aaron Henry |

| T. R. M. Howard |

| Jesse Jackson |