Alberto Santos-Dumont facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

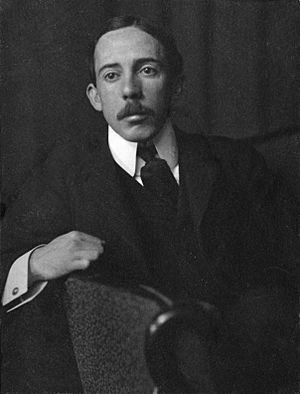

Alberto Santos-Dumont

|

|

|---|---|

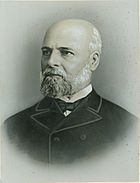

Santos-Dumont in 1902

|

|

| Born | 20 July 1873 Palmira, Minas Gerais, Empire of Brazil

|

| Died | 23 July 1932 (aged 59) |

| Resting place | Cemitério de São João Batista |

| Occupation | Aeronaut, inventor |

| Known for | No. 6 14-bis Demoiselle |

| Parents |

|

| Awards |

|

| Signature | |

|

|

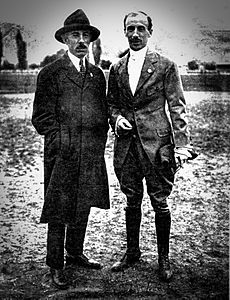

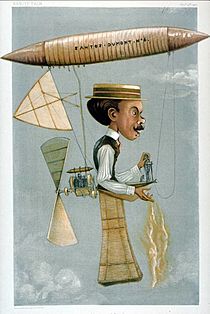

Alberto Santos-Dumont (born in Palmira, Brazil, on 20 July 1873 – died in Guarujá, Brazil, on 23 July 1932) was a brilliant Brazilian aeronaut, inventor, and sportsman. He made huge contributions to the early development of both lighter-than-air (like airships) and heavier-than-air (like airplanes) flying machines.

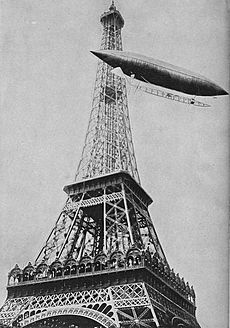

Santos-Dumont came from a rich family that grew coffee. He spent most of his adult life in Paris, France, where he studied and experimented with flying. He designed, built, and flew the first powered airships. In 1901, he won the Deutsch Prize by flying his airship, No. 6, around the Eiffel Tower. This made him one of the most famous people in the world!

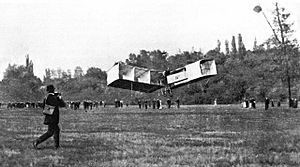

Later, Santos-Dumont moved on to building heavier-than-air machines. On 23 October 1906, he flew his fixed-wing aircraft, the 14-bis (also called the Oiseau de Proie, meaning "bird of prey"), for about 60 meters. It flew two to three meters high at the Bagatelle Gamefield in Paris, taking off all by itself without any help. On 12 November, in front of a big crowd, he flew 220 meters at a height of six meters. These were the first heavier-than-air flights officially watched and certified by important aviation groups like the Aeroclub of France and the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale.

In Brazil, Santos-Dumont is a national hero. Many people there believe he flew a practical airplane before the Wright brothers. Lots of roads, plazas, schools, monuments, and airports in Brazil are named after him. His name is even written on the Tancredo Neves Pantheon of the Fatherland and Freedom, a special place for national heroes.

Contents

Early Life and Dreams

Alberto Santos-Dumont was the sixth of eight children born to Henrique Dumont, an engineer, and Francisca de Paula Santos. In 1873, his family moved to a small town called Cabangu so his father could work on building the D. Pedro II railroad.

Even as a very young child, Alberto showed an interest in flying. His parents said that when he was just one year old, he would pop rubber balloons to see what was inside!

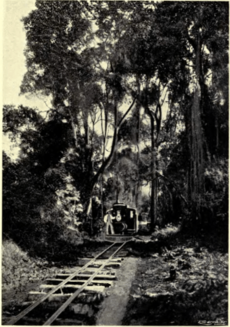

The family later moved to Ribeirão Preto, where they owned a large coffee farm. Alberto was taught by his older sister until he was 10. He went to several schools but only studied what truly interested him. He loved reading books in his father's library.

At 15, in 1888, he saw his first human flight in São Paulo. An aeronaut went up in a balloon and then parachuted down. After a family trip to Paris in 1891, he became very interested in mechanics, especially internal combustion engines. He never stopped looking for new ideas.

Santos-Dumont loved his childhood on the farm. He said:

"I lived a free life there, which was essential to form my personality and love for adventure. Since childhood, I had a great love for mechanical things. My greatest joy was taking care of my father's machines. That was my special job, which made me very proud."

He was driving the farm's trains at age seven and could operate a locomotive by himself at twelve! But the speed on land wasn't enough for him. He dreamed of flying.

Reading the books of Jules Verne made him want to conquer the air. Verne's stories about submarines, balloons, and other vehicles deeply impressed the young boy. Years later, he still remembered those imaginary adventures.

Technology fascinated him. He built kites and small airplanes powered by twisted rubber bands. Every year, on 24 June, he would launch many tiny silk balloons over bonfires to watch them float into the sky.

Aviation Career Begins

Exploring the Skies

In 1891, at 18, Santos-Dumont visited Europe. He climbed Mont Blanc, a very tall mountain, which gave him a taste for heights. His father had an accident in 1892 and encouraged Alberto to focus on learning mechanics, chemistry, and electricity. Alberto returned to France and began serious technical studies.

By 1897, Santos-Dumont was 24 and had inherited a lot of money. He used it to fund his projects, so he didn't need to report to any investors. He hired professional balloonists to teach him. On 23 March 1898, he made his first balloon ascent. He said: "I will never forget the genuine pleasure of my first balloon ascent."

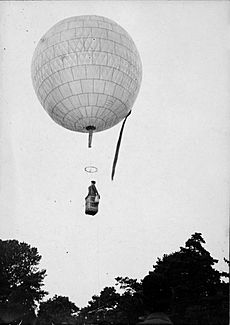

He soon became known for his ballooning. By 1900, he had created nine balloons. Two became famous: the Brazil and the Amérique. The Brazil first flew on 4 July 1898. It was the smallest aircraft built at the time, weighing only 27.5 kg without the pilot. It made over 200 flights! The Amérique was larger and could carry passengers. Santos-Dumont even faced storms and accidents with it.

Mastering Airships

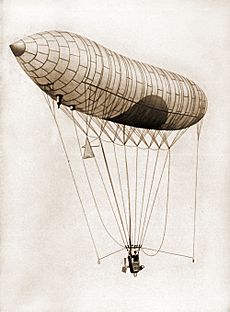

Airships, which are powered balloons, had been tried before but not fully mastered. Santos-Dumont decided to use a lightweight internal combustion engine instead of heavy electric motors. He modified an engine, making it a 3.5 horsepower unit. This was the first successful use of an internal combustion engine in aviation!

Santos-Dumont believed his work on airships was truly about aviation. He said that the hydrogen gas alone wasn't enough to make them fly; they also needed engine power. He thought that flying machines would slowly get better, like a caterpillar turning into a butterfly.

- No. 1

His first airship, No. 1, was 25 meters long. Its first flight attempt in February 1898 ended in a crash due to snowy conditions. It was repaired and flew again on 18 September 1898. However, the air pump didn't work, and the airship bent and fell quickly from 400 meters. Santos-Dumont managed to escape safely.

- No. 2

In 1899, he built No. 2, which was similar but had a fan to keep it rigid. Its first test on 11 May 1899, ended with the airship getting caught in trees due to rain and wind.

- No. 3

In September 1899, Santos-Dumont built No. 3, a longer airship. On 13 November, he took off in No. 3 and flew around the Eiffel Tower for the very first time! He landed exactly where his No. 1 had crashed, but this time, he was in control.

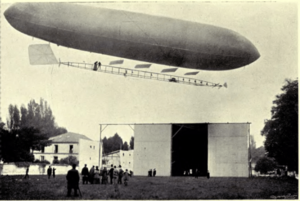

He then had a large hangar built at Saint-Cloud to house his airships and make hydrogen gas. This hangar was finished on 15 June 1900.

- No. 4

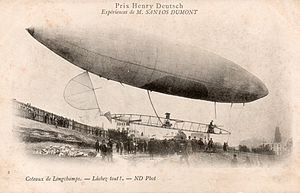

On 24 March 1900, a rich oil businessman named Henri Deutsch de la Meurthe offered a prize of 100,000 francs. This "Deutsch Prize" would go to anyone who could invent an efficient flying machine. The challenge was to fly from Saint-Cloud to the Eiffel Tower, circle it, and return to the starting point in under 30 minutes. This was a total distance of 11 kilometers, requiring a speed of at least 22 km/h.

This prize encouraged Santos-Dumont to build faster airships. No. 4 was 29 meters long. It had a bamboo frame and a 7 horsepower engine that powered a front propeller. The pilot sat on a bicycle saddle and used pedals to start the engine. Santos-Dumont made almost daily flights in No. 4 during August 1900, showing how well it could fly against the wind. Everyone thought he would win the Deutsch Prize.

- No. 5 and No. 6

No. 5 was built specifically to win the Deutsch Prize. It had a new design with a triangular basket and used piano wire to reduce drag. It was powered by a 12 horsepower engine.

On 13 July 1901, Santos-Dumont tried for the prize with No. 5. He completed the course but took ten minutes longer than the 30-minute limit. On 8 May, trying again, he crashed his airship into a hotel. The balloon exploded, but he was unharmed. He publicly tested the engine to show it was still working.

On 19 October 1901, using his No. 6 airship, which had a 20 horsepower engine, he completed the flight in 29 minutes and 30 seconds! However, it took him about a minute to land, so the committee first said he didn't win. But the public and Deutsch himself believed he had won. After some discussion, the decision was changed. Santos-Dumont became known worldwide as the greatest aviator and the inventor of the airship. He shared his 100,000 franc prize money with his staff and unemployed workers in Paris.

After winning, Santos-Dumont received congratulations from many countries. Magazines published stories about him. Alexander Graham Bell even talked about his success in an interview. Tributes were paid in France, Brazil, and England. The President of Brazil sent him prize money and a gold medal. In January 1902, Albert I, Prince of Monaco invited him to continue his experiments there, offering a new hangar. Santos-Dumont's success even inspired fictional characters like Tom Swift.

In April 1902, Santos-Dumont visited the United States and met Thomas Edison. They talked about patents, and Santos-Dumont said he didn't plan to patent his aircraft. He was even received by President Theodore Roosevelt at the White House.

- Monaco

In Monaco, Santos-Dumont built a large hangar by the sea. He found that flying over water helped stabilize his aircraft. He reached speeds of up to 42 km/h. His success showed how useful aircraft could be, even for military purposes. However, his flights in Monaco were stopped by a crash on 14 February 1902, when his No. 6 airship was damaged.

- Nos. 7, 8, 9 and 10

Santos-Dumont continued building new airships. No. 7 was a racing airship, tested in May 1904. It was later sabotaged in the United States. No. 8 was a copy of No. 6. No. 9 was a smaller "travel airship" that Santos-Dumont flew many times in 1903, including the first night flight of an airship. On 14 July, he even took part in a military parade, firing 21 shots from a revolver as he passed the President! The military saw his balloons as useful for war.

The first woman to fly an aircraft was Aida de Acosta, who flew No. 9 on 29 June 1903.

No. 10 was a very large airship, big enough to carry several people and serve as public transport. It made a few flights in October 1903 but was never fully finished. He also worked on a helicopter (No. 12) but couldn't finish it due to technology limits.

In 1903, when he returned to Rio de Janeiro, a banner was put up on Sugarloaf Mountain to greet him as a hero. He met the President of Brazil, Rodrigues Alves. In 1904, he was honored by France and published his book Dans L'Air.

Achieving Heavier-than-Air Flight

In October 1904, new aviation prizes were created in France. The Archdeacon Prize offered 3,500 francs for a flight of 25 meters. The French Aeroclub Prize offered 1,500 francs for 100 meters. These prizes encouraged inventors to push the limits of flight.

Other inventors had already made progress. In Germany, Otto Lilienthal had made thousands of glider flights. In the United States, the Wright brothers had been making longer flights since 1903, but their takeoffs often used catapults or strong headwinds, and they didn't have official observers.

Designing the 14-bis

Santos-Dumont began studying how to make heavier-than-air machines fly. He built a helicopter model, No. 12, but stopped because he couldn't find a light, powerful enough engine. He then tested the No. 14 airship, which flew in two versions.

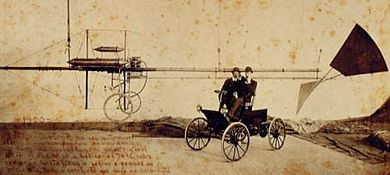

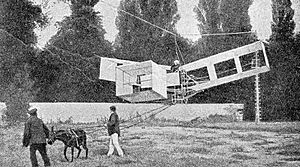

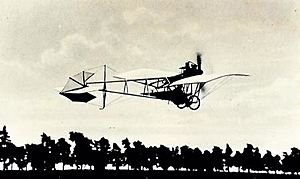

He then built a unique machine, the 14-bis, also known as the Oiseau de Proie (Bird of Prey). It was first attached to a hydrogen balloon to help with takeoff. He tested it in mid-1906. He realized that while the balloon helped with takeoff, it created too much drag. So, he removed the balloon.

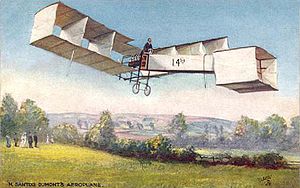

The Oiseau de Proie was inspired by other designs. It was a biplane (two wings) with a cellular structure, like a box kite, which gave it good support. It was 4 meters high, 10 meters long, and had a wing span of 12 meters. It weighed 205 kilograms. The rudder was in front, and the propeller was at the back, powered by a 24 horsepower engine. The pilot stood upright.

On 29 July, Santos-Dumont used a donkey and cables to hoist the Oiseau de Proie to the top of a 13-meter tower. The plane then glided down a steel wire. This helped him get a feel for the aircraft and study its balance. On 13 September, the 14-bis made a 7-meter test flight.

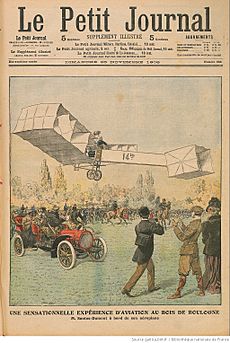

Historic Flights

On 23 October 1906, Santos-Dumont presented the Oiseau de Proie II at Bagatelle. He had varnished the plane to make it lighter and removed the rear wheel. At 4:45 pm, he started the engine. The plane lifted off and flew for 60 meters! It took off without any help from headwinds, ramps, or catapults. Europeans at the time believed this was the first such flight.

The crowd cheered and carried him in triumph. The judges were so excited they forgot to time the flight, so it wasn't officially recorded. A new test was scheduled for 12 November. Santos-Dumont said:

"I struggled at first with great difficulty to make the airplane obey completely. It was like shooting an arrow with the tail forward. On my first flight, after sixty meters, I lost direction and crashed... I didn't stay in the air longer, not because of the machine's fault, but purely my own."

To prepare for the next test, Santos-Dumont added two octagonal surfaces, which were early versions of ailerons, to the wings for better control. He called this version the Oiseau de Proie III. Santos-Dumont was a pioneer in using ailerons.

On 12 November 1906, he made five public flights at Bagatelle. His longest flight was 220 meters, lasting 21 seconds, at an average speed of 37.4 km/h. He won the French Aeroclub Award! These were the first airplane flights ever recorded by a film company.

He made more changes to the aircraft, calling it Oiseau de Proie IV. On 4 April 1907, it flew for 50 meters, crashed, and was destroyed. The project was then stopped.

New Airplane Designs

Santos-Dumont continued to design new airplanes. He made the No. 15, a biplane with a rear rudder, and the No. 16, a mix of airship and airplane, but these were not successful.

He then created a new series of smaller, more refined aircraft, like the famous Demoiselle. It was first tested in November 1907. The Demoiselle No. 20, improved in 1909, is considered "the first ultralight in history." This airplane was designed for sports competitions, and about 300 were built in Europe and the United States. Santos-Dumont even published the blueprints so others could build it. This plane cemented his role in the beginning of aviation in the 20th century. The Demoiselle could fly up to 2 kilometers and reach 96 km/h.

The Demoiselle is now on permanent display at the Musée de l'air et de l'espace in France.

Later Life and Legacy

Santos-Dumont began to experience health problems. He looked older and felt too tired to keep up with new inventors in races. On 22 August 1909, he attended the Great Aviation Week in Reims, where he made his last flights. After an accident with the Demoiselle on 4 January 1910, he closed his workshop and withdrew from public life. He still worked to promote aviation.

In August 1914, World War I began. Airplanes started to be used in war, first for observation and then for fighting. Santos-Dumont saw his dream of peaceful flight turn into a nightmare. This deeply saddened him.

He moved to Trouville and studied astronomy. His neighbors mistakenly thought he was spying for the Germans because of his observation devices, and he was arrested. After the misunderstanding was cleared up, the French government apologized. This incident made him feel very depressed, and he destroyed many of his aeronautical documents.

In 1915, his health worsened, and he returned to Brazil. He spoke at a conference in the United States, expressing concern about airplanes being used as weapons but also suggesting they could be used for coastal defense. He also advocated for the peaceful use of airplanes.

In 1918, Santos-Dumont bought land in Petrópolis and built a unique house filled with his own mechanical inventions, including a special shower. He called it "The Enchanted" (A Encantada). The outside stairs have steps dug alternately for the right and left foot, making them easier to climb. This house is now a museum.

In 1920, he started an international campaign against using aircraft for war, but it was not successful. He made his last balloon ascent in 1922.

In January 1926, he asked the League of Nations to stop the use of airplanes as weapons of war. He even offered money to anyone who wrote the best essay against military use of airplanes. Santos-Dumont was the first aviator to speak out against it.

In May 1927, he was invited to a banquet for Charles Lindberg (who flew across the Atlantic Ocean), but he couldn't attend due to his health. He became increasingly depressed.

On 3 December 1928, he returned to Brazil. The city of Rio de Janeiro welcomed him with honors. However, a seaplane named after him, carrying several professors, crashed while flying over his ship. This tragic event deeply affected him. He stayed in his hotel and only left for the funerals.

Santos-Dumont's health continued to decline. He passed away on 23 July 1932, during the Constitutionalist revolution in Brazil, a conflict where airplanes were used. He was horrified by the use of his invention in war. His death certificate stated the cause as a heart attack.

His body was buried in São João Batista Cemetery in Rio de Janeiro on 21 December 1932, under a replica of the Icarus statue he had built. A doctor secretly removed his heart during the embalming process. After many years, the heart was donated to the Brazilian government and is now on display at the Air Force Museum in Campo dos Afonsos, Rio de Janeiro.

Honors and Tributes

On 25 July 1909, Louis Blériot crossed the English Channel. Santos-Dumont congratulated him, saying, "One day, perhaps, thanks to you, the airplane will cross the Atlantic." Blériot replied, "I have done nothing but follow and imitate you. Your name to the aviators is a flag. You are our leader."

Santos-Dumont's image was used on products, his unique hat and collar were copied, and his balloons were made into toys. The Aéro-Club de France honored him with two monuments: one in 1910 at Bagatelle, where he flew the Oiseau de Proie, and another in 1913 in Saint-Cloud, celebrating his airship flight.

On 31 July 1932, the town of Palmira, where he was born, was renamed Santos-Dumont. On 4 July 1936, 23 October was declared "aviator's day" in Brazil, celebrating his historic flight. On 16 October 1936, Rio de Janeiro's first airport was named after him.

His birthplace in Cabangu is now the Cabangu Museum. In 1959, he was made an honorary air marshal. In 1976, the International Astronomical Union named a lunar crater after him. He is the only South American to receive this honor. In 1984, he was given the title "Patron of the Brazilian Aeronautics." In 1997, then-President of the United States, Bill Clinton, called Santos-Dumont the "father of aviation."

In 2005, the Brazilian Space Agency and the Russian Federal Space Agency launched the Missão Centenário (Centennial Mission), sending Brazilian astronaut Marcos César Pontes to the International Space Station. This mission honored the 100th anniversary of Santos-Dumont's 14-bis flight. In 2006, his name was added to the Steel Book of National Heroes in Brasília, making him a National Hero.

Cultural Impact

In 1902, a poet wrote a song called "The Conquest of the Air" in his honor. The Brazilian Post Office has released several stamps celebrating his achievements. In 2006, the Brazilian Central Bank issued a coin to commemorate his invention. He was also featured on Brazilian banknotes.

The jewelry company Cartier created a series of watches named after Santos-Dumont, celebrating their partnership.

During the opening ceremony of the 2016 Summer Olympic Games in Rio de Janeiro, a replica of Santos-Dumont's 14-bis flew over the stadium, seeming to take off for a flight over the city.

Santos-Dumont has been shown in many films, TV shows, and plays. In 2019, HBO released a miniseries called Santos-Dumont, which followed his life from his childhood on the coffee fields to his historic flights in Paris.

Works

- Translations of his works

- "Os Meus Balões" (1938). Translated to Portuguese by Arthur de Miranda Bastos.

- "O Homem Mecânico": published in Portuguese in the work "Os Balões de Santos-Dumont", 2010.

- Non published

- "L'Homme Mécanique", typescript from 1929.

- A book of 13 chapters, untitled, addressing aeronautical events of the 18th to 20th centuries.

See Also

In Spanish: Alberto Santos Dumont para niños

In Spanish: Alberto Santos Dumont para niños

- Aeronautics engineer

- List of aerospace engineers

- Early flying machines

- List of early flying machines

- List of firsts in aviation

Images for kids

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |