Louis Blériot facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Louis Blériot

|

|

|---|---|

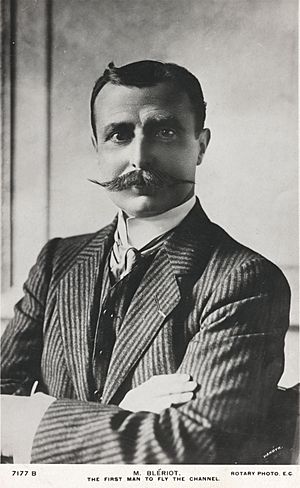

Blériot around 1911

|

|

| Born |

Louis Charles Joseph Blériot

1 July 1872 |

| Died | 1 August 1936 (aged 64) |

| Alma mater | École Centrale Paris |

| Occupation | Inventor and engineer |

| Known for | First heavier-than-air flight across the English Channel, first working monoplane |

| Spouse(s) | Alice Védère (1901) (1883-1963) |

| Awards | Commandeur, Légion d'honneur Prix Osiris |

Louis Charles Joseph Blériot (born July 1, 1872 – died August 1, 1936) was a French aviator, inventor, and engineer. He created the first useful headlamp for cars. He built a successful business making these lamps. He used a lot of his money to fund his dream of building a working airplane.

Blériot was the first to use the control system we still see in airplanes today. This system uses a hand-operated joystick and foot pedals for steering. He was also the first to build a working, powered, piloted monoplane (an airplane with one set of wings). In 1909, he became world-famous for being the first person to fly an airplane across the English Channel. He won a £1,000 prize from the Daily Mail newspaper for this amazing feat. He also founded Blériot Aéronautique, a very successful company that built airplanes.

Contents

Early Life and Inventions

Louis Blériot was born in Cambrai, France. He was the oldest of five children. When he was 10, he went to a boarding school in Cambrai. He often won prizes there, especially for engineering drawing. At 15, he moved to a high school in Amiens.

After finishing high school, he wanted to join the famous École Centrale Paris in Paris. He studied hard for a year to pass the tough entrance exam. He got in, doing very well in engineering drawing. After three years of challenging studies, he graduated. Then, he spent a year in the military.

Later, Blériot worked for an electrical engineering company in Paris. He left this job after inventing the world's first practical headlamp for cars. This lamp used a special acetylene generator. In 1897, Blériot opened his own headlamp showroom in Paris. His business did very well. Soon, he was selling his lamps to top car makers like Renault and Panhard-Levassor.

In 1900, Blériot met Alice Védères and fell in love. He was determined to marry her, and they got married on February 21, 1901.

Early Aviation Experiments

Blériot became interested in flying while at engineering school. His serious experiments likely started after seeing Clément Ader's airplane at the 1900 World's Fair. His headlamp business was doing well, so he had money and time for aviation.

His first flying attempts were with ornithopters, which are machines that try to fly by flapping wings like a bird. These were not successful. In 1905, Blériot met Gabriel Voisin, who was working on experimental gliders.

Blériot watched Voisin's first tests of a floatplane glider. Blériot, who enjoyed photography, even filmed the flight. The success of these tests made him ask Voisin to build a similar glider for him, called the Blériot II. In July 1905, a test flight of this glider ended in a crash. Voisin almost drowned, but Blériot was not discouraged. He suggested that Voisin partner with him.

Voisin agreed, and they formed a company, possibly the world's first aircraft manufacturing company. This company built two powered aircraft, the Blériot III and the Blériot IV, but they were not successful. These planes used lightweight Antoinette engines.

The Blériot IV was damaged in an accident in November 1906. This was disappointing, especially as Alberto Santos Dumont made a successful flight of 220 meters (720 feet) on the same day. Blériot witnessed this flight. After this, Blériot ended his partnership with Voisin. He started his own company, Recherches Aéronautiques Louis Blériot. Here, he began creating his own aircraft designs. He tried many different setups and eventually built the world's first successful powered monoplane.

His first new design, the Blériot V, was a canard type (with the small wing at the front). He first tested it in March 1907. After several attempts, he made a short flight of about 6 meters (20 feet) in April. Later, the plane crashed and was mostly destroyed, but Blériot was lucky and not hurt.

Next came the Blériot VI, a tandem wing design (two wings, one behind the other). In July 1907, he made a successful flight of about 25–30 meters (84–100 feet) at an altitude of 2 meters (7 feet). This was his first truly successful flight. He made more flights that month, including one of 150 meters (490 feet). In August, he reached 12 meters (39 feet) high, but the propeller broke, causing a hard landing. He then put a more powerful engine in it. On September 17, the plane reached 25 meters (82 feet) high, but the engine stopped. The plane crashed, but Blériot was only slightly cut. After this, he moved on to his next design.

The Blériot VII was a monoplane with a tail like modern planes. This plane, which first flew in November 1907, is known as the first successful monoplane. In December, Blériot flew it over 500 meters (1,640 feet) twice, even making a U-turn. This was a big achievement for French aviators. However, the plane crashed and was wrecked after a later flight.

Blériot's next plane, the Blériot VIII, was shown in February 1908. This plane was the first to successfully use the combination of a hand-operated joystick and foot-operated rudder controls. After some changes, it worked well. On October 31, 1908, he made a cross-country flight of 28 kilometers (17 miles). This was almost the first cross-country flight, as Henri Farman had flown a similar distance the day before.

At the first Paris Aero Salon in December 1908, Blériot showed three aircraft: the Blériot IX monoplane, the Blériot X biplane, and the Blériot XI. The first two never flew. The Blériot XI became his most successful model. It first flew in January 1909. It flew well, but its engine often overheated. Blériot then contacted Alessandro Anzani, who made reliable motorcycle engines. Anzani also worked with Lucien Chauvière, who designed an excellent propeller. The combination of a good engine and an efficient propeller made the Type XI very successful.

Soon after, he flew the Blériot XII, a two-seater monoplane. He flew it with one passenger in July, and then made the world's first flight with two passengers. One of the passengers was Santos Dumont. A few days later, the engine broke. Blériot then went back to testing the Type XI. In June 1909, he made his longest flight yet, lasting over 36 minutes. In July, he flew the Type XI for 50 minutes and made a cross-country flight of 41 kilometers (25 miles). Blériot was very determined. During one flight, part of the engine insulation came loose and burned his shoe. He was in pain but kept flying until the engine failed. He suffered severe burns, which took over two months to heal.

In June 1909, Blériot and Voisin won the Prix Osiris, a major French science award. A few days later, Blériot told the Daily Mail newspaper that he planned to try to win their £1,000 prize for flying across the English Channel.

1909 Channel Crossing

The Daily Mail prize was first announced in 1908. Many people thought it was just a publicity stunt, believing no one could win it. The English Channel had been crossed many times by balloon since 1785.

Blériot planned to fly across the Channel in his Type XI monoplane. He had three main rivals for the prize. The strongest rival was Hubert Latham, a French pilot flying an Antoinette IV monoplane. Latham was favored to win. The other rivals were Charles de Lambert and Arthur Seymour.

Latham arrived in Calais, France, in early July and set up his base. There was huge public interest, with thousands of visitors in Calais and Dover. The Marconi Company even set up a special radio link for the event. The weather was windy, so Latham couldn't try until July 19. He flew about 6 miles (10 km) from Dover when his engine had trouble. He had to make the world's first landing of an aircraft on the sea. Latham was rescued by a French destroyer and taken back to France.

Blériot arrived in Calais on July 21 with his mechanics and a friend, Alfred Leblanc. They set up their base near the beach. The next day, Latham got a new plane. The wind was too strong for flights on Friday and Saturday, but it started to calm down on Saturday evening.

Leblanc woke Blériot at 2:00 AM, judging the weather was perfect. Blériot was unsure at first but soon felt better. By 3:30 AM, his wife Alice was on the French destroyer Escopette, which would escort the flight.

At 4:15 AM on July 25, Blériot made a short test flight. Then, at 4:41 AM, he took off to attempt the crossing. He flew at about 45 miles per hour (72 km/h) at an altitude of about 76 meters (250 feet). He headed across the Channel. He didn't have a compass, so he followed the Escopette. But he soon flew faster than the ship.

Visibility got worse, and Blériot later said he was "alone, isolated, lost in the midst of the immense sea" for over 10 minutes. Then, he saw the English coast to his left. The wind had blown him east of his planned course. He changed direction and followed the coast. He saw a correspondent from Le Matin waving a large French flag as a signal. Blériot had not visited Dover to find a landing spot, so the correspondent had chosen a gently sloping field near Dover Castle.

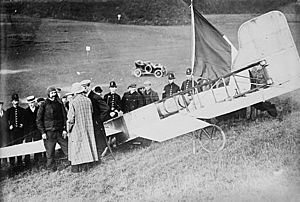

Once over land, Blériot circled twice to lose height. He cut his engine at about 20 meters (65 feet) high. He made a heavy landing because of the gusty wind. The landing gear was damaged, and one propeller blade broke, but Blériot was unharmed. The flight took 36 minutes and 30 seconds.

News of his flight had been sent to Dover by radio. Blériot was taken to the harbor and reunited with his wife. They were surrounded by a cheering crowd and photographers. Blériot had become a celebrity.

A memorial marks his landing spot near Dover Castle. It is an outline of his aircraft made from granite stones in the grass. The aircraft he used for the crossing is now in the Musée des Arts et Métiers in Paris.

Later Life and Legacy

Blériot's success changed his company immediately. Before the Channel flight, he had spent a lot of money on his aviation experiments. Now, his investment paid off. Orders for his Type XI aircraft quickly came in. By the end of 1909, he had received orders for over 100 planes, each selling for 10,000 francs.

In August 1909, Blériot flew at a big aviation meeting in Reims, France. He almost won the first Gordon Bennett Trophy, but Glenn Curtiss narrowly beat him. However, Blériot won the prize for the fastest lap, setting a new world speed record for aircraft.

Blériot continued flying at other aviation meetings in Europe. In December 1909, his luck ran out at a meeting in Istanbul. He crashed on top of a house, breaking several ribs and suffering internal injuries. He was in the hospital for three weeks.

Between 1909 and the start of World War I in 1914, Blériot produced about 900 aircraft. Most of them were variations of his Type XI model. Blériot's monoplanes and Voisin-type biplanes were very popular before the war. There were some concerns about the safety of monoplanes. The French government temporarily stopped using all monoplanes in the army in 1912 after some accidents. However, they lifted the ban after tests showed Blériot's analysis was correct, and improvements were made to the planes.

From 1910, Blériot was involved in a five-year legal fight with the Wright Brothers over their wing-warping patents. The Wrights' claims were dismissed in French and German courts.

By 1913, Blériot's aviation activities were handled by Blériot Aéronautique. This company continued to design and produce aircraft until 1937. In 1913, Blériot led a group that bought another aircraft manufacturer, Deperdussin. He became the president of this company in 1914 and renamed it Société Pour L'Aviation et ses Dérivés (SPAD). SPAD produced famous World War I fighter aircraft like the SPAD S.XIII.

Before World War I, Blériot opened British flying schools. In 1915, he set up the Blériot Manufacturing Aircraft Company Ltd. in Britain. He hoped to sell planes to the British government, but his designs were seen as old-fashioned. The company closed in 1916. Blériot then started a new company in the UK, which later became the Air Navigation and Engineering Company (ANEC). ANEC made cars and motorcycles, as well as light aircraft, until 1926.

In 1927, Blériot, who had stopped flying, was there to welcome Charles Lindbergh when he landed in Paris after his transatlantic flight. Both men had made history by crossing large bodies of water, and they shared a photo in Paris. In 1934, Blériot visited Newark Airport in New Jersey and predicted that commercial overseas flights would happen by 1938.

Death

Louis Blériot remained active in the aviation business until he died on August 1, 1936, in Paris. He passed away from a heart attack. After a funeral with full military honors, he was buried in the Cimetière des Gonards in Versailles.

Legacy

In 1930, Blériot himself created the Blériot Trophy. This was a one-time award for the first aircrew to fly at an average speed of over 2,000 kilometers per hour (1,242 miles per hour) for half an hour. This was a very ambitious goal for that time.

In 1936, the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale created the "Louis Blériot medal" in his honor. This medal can be given up to three times a year to people who set records for speed, altitude, and distance in light aircraft. It is still awarded today.

In 1967, Blériot was added to the International Air & Space Hall of Fame.

On July 25, 2009, exactly 100 years after Blériot's Channel crossing, a Frenchman named Edmond Salis flew a replica of Blériot's aircraft from France to England. He landed successfully in Kent, England.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Louis Blériot para niños

In Spanish: Louis Blériot para niños

- Blériot Aéronautique

- Early flying machines

- List of firsts in aviation