Clémence Royer facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Clémence Royer

|

|

|---|---|

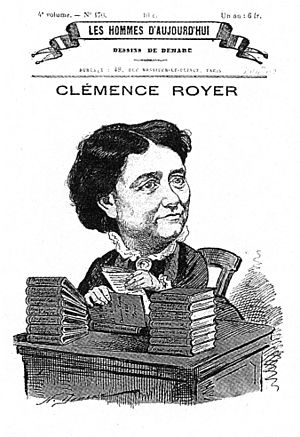

Photograph of Clémence Royer taken by Félix Nadar in 1865.

|

|

| Born | 21 April 1830 |

| Died | 6 February 1902 (aged 71) Neuilly-sur-Seine, France

|

Clémence Royer (born April 21, 1830 – died February 6, 1902) was a smart French woman who taught herself many things. She gave talks and wrote books about money, ideas, science, and women's rights. She is most famous for her French translation of Charles Darwin's important book, On the Origin of Species, which she published in 1862. Her translation was quite famous, but also caused some debate.

Contents

Clémence Royer's Early Life

Clémence Royer was born in Nantes, France, on April 21, 1830. Her birth name was Augustine-Clémence Audouard. Seven years later, when her parents got married, her name changed to Clémence-Auguste Royer. Her father was an army captain who supported the king. After a failed rebellion in 1832 to bring back the old royal family, her family had to live in Switzerland for four years. They later returned to France, where her father was tried but found innocent.

Clémence was mostly taught at home by her parents. When she was 10, she went to a convent school but didn't stay long. She continued her education at home. At 13, she moved to Paris with her parents. As a teenager, she loved reading plays and novels. She also believed in no religion.

When she was 18, the 1848 revolution happened in France. This event greatly influenced her, and she started to support republican ideas, which were different from her father's views. A year later, her father passed away, and she received a small inheritance. For the next three years, she studied on her own. She earned special papers in math, French, and music, which allowed her to become a teacher.

In 1854, at age 23, she started teaching at a girls' school in Wales. She taught there for a year before returning to France in 1855. She taught at two more schools in France. During this time, she began to seriously question her religious beliefs. A famous writer, Ernest Renan, once said she was "almost a man of genius." This shows how people in the 1800s sometimes struggled to call a woman a true genius.

Life in Lausanne, Switzerland

In June 1856, Clémence Royer stopped teaching and moved to Lausanne, Switzerland. She used the money she inherited from her father to live there. She spent her time studying, borrowing many books from the public library. She first studied the beginnings of Christianity, then moved on to different science topics.

In 1858, she was inspired by a public talk given by a Swedish writer. Royer then gave four lectures on logic, which were only for women. These talks were very popular. Around this time, she met a group of French thinkers and republicans who were living in exile in Lausanne. One of them was Pascal Duprat, a former French politician. He taught political science and edited two journals. He was 15 years older than Clémence.

Clémence began helping Duprat with his journal, Le Nouvel Économiste. He encouraged her to write and helped her promote her lectures. She started another series of lectures for women, this time about natural philosophy. Duprat's publisher printed her first lecture, Introduction to the Philosophy of Women. This lecture showed her early ideas about the role of women in society. Duprat later moved to Geneva, but Royer continued to write for his journal. They became close friends and later had a son together.

In 1860, a Swiss area offered a prize for the best essay on income tax. Royer wrote a book about the history and practice of this tax, and it won second prize. Her book was published in 1862. It also talked about the economic role of women and their importance in family life. This book helped her become known outside Switzerland.

In 1861, Royer visited Paris and gave more lectures. A countess named Marie d'Agoult attended these talks. She shared many of Royer's ideas about government. The two women became friends and wrote many letters to each other. Royer often sent articles she had written for the Journal des Économistes.

Translating On the Origin of Species

It's not fully known how Clémence Royer got the job to translate Charles Darwin's famous book, On the Origin of Species. Darwin really wanted his book to be published in French. His first choice for a translator said no because the book was too technical. Royer knew a lot about the ideas of other scientists like Jean-Baptiste Lamarck and Thomas Malthus. She understood how important Darwin's work was. She also likely had good connections with a French publisher.

Darwin sent her a copy of his book in September 1861. A Swiss scientist, René-Édouard Claparède, offered to help her with the difficult biology parts.

Royer did more than just translate. She added a long introduction (60 pages) and many detailed notes. In her introduction, she shared her own ideas about science and religion. She also discussed how Darwin's idea of natural selection might apply to humans. She had some controversial views about helping those who were weak or sick, suggesting it might have negative effects on human progress. These ideas made her quite famous, but also caused a lot of discussion. Her introduction also promoted her own idea of evolution, which was a bit different from Darwin's.

In June 1862, Darwin received a copy of her translation. He wrote to a friend, saying that Royer "must be one of the cleverest & oddest women in Europe." He noted that she believed natural selection could explain everything about human behavior and politics.

However, Darwin also had some doubts. He wished she knew more about natural history. He was unhappy with her notes, saying that when he expressed doubt in his book, she would add a note saying there was no difficulty at all! He found this quite strange.

Later Editions of the Translation

For the second French edition, published in 1866, Darwin suggested some changes. Royer also changed some of her controversial statements in the introduction. She added a new foreword that supported free thinkers and complained about criticism from religious groups.

Royer published a third edition without talking to Darwin first. She removed her foreword but added a new introduction where she directly disagreed with Darwin's idea of pangenesis. She also made a big mistake by not updating her translation to include changes Darwin had made in his later English editions. When Darwin found out, he arranged for a new translation of his book to be made by someone else.

Life in Italy and Motherhood

Royer's translation of On the Origin of Species made her well-known. She was often asked to give talks about Darwin's ideas. She spent the winter of 1862-1863 lecturing in Belgium and the Netherlands. She also wrote her only novel, Les Jumeaux d’Hellas, which was published in 1864 but wasn't very successful. She continued to write book reviews and reports for the Journal des Économistes. During this time, she often met with Pascal Duprat at various meetings across Europe.

In August 1865, Royer moved back to Paris from Lausanne. Duprat, who was not allowed to live openly in France at the time, secretly joined her. Three months later, in December, they moved to Florence, Italy, where they lived openly together. Their only son, René, was born there on March 12, 1866. With a young child, she couldn't travel as much, but she kept writing. She wrote articles about Jean-Baptiste Lamarck and worked on a book about the evolution of human society, published in 1870. This book discussed topics that Darwin later wrote about in his book, The Descent of Man.

In her book, Royer wrote that the struggle for existence was always happening, not just between different animal types, but also among people within the same group. She believed human society had evolved over time to higher stages. She thought that differences among people were natural due to evolution. She also argued that it was okay for stronger groups to fight and even get rid of weaker ones, unless the weaker ones were useful for work. While she thought mixing different groups could be good, she generally felt it was wrong. However, within advanced societies, she was against war, believing competition should be peaceful.

Royer supported a lot of freedom for people, thinking it would help natural selection and improve humanity. But she was against ideas that made everyone equal, and she didn't support charity or welfare that would keep "unfit" people alive. Even with these views, Royer believed that women were not naturally less capable than men. She thought that women's lower position in society was a mistake and that societies that didn't let women fully participate would fall behind. She also believed that religion, especially Christianity, stopped progress. Because of these ideas, she is seen as an early supporter of Social Darwinism in Europe.

In late 1868, Duprat left Florence. In 1869, as the political situation in France became calmer, Royer returned to Paris with her son. This move allowed her mother to help raise her child.

Life in Paris and Scientific Societies

Even though Darwin had taken back his permission for Royer's translation, she continued to support his ideas. When she arrived in Paris, she started giving public talks about evolution. Darwin's ideas had not yet become very popular among French scientists. Many thought there wasn't enough proof for evolution. In 1870, Royer became the first woman in France to be chosen for a scientific group. She was elected to the important all-male Société d’Anthropologie de Paris (Anthropological Society of Paris). She was the only woman member for the next 15 years. She was very active in the society, joining discussions on many topics and writing articles for their journal.

From the society's reports, most members seemed to accept that evolution had happened. However, they rarely talked about Darwin's main idea, natural selection. They often saw Darwin's ideas as just an extension of Lamarck's. In other scientific groups in France, the idea of evolution was hardly mentioned at all.

Royer always liked to challenge common beliefs. In 1883, she wrote a paper questioning Newton's law of universal gravitation and criticizing the idea of "action at a distance" (how gravity works over a distance). The journal that published her paper even added a note saying they didn't agree with her ideas.

Duprat passed away suddenly in 1885. Because of French law, Royer and her son had no legal claim to his money. Royer had very little income, and her son was studying at a special school. Her writings for important journals didn't pay her. She was in a difficult financial situation and had to ask the government for money each year.

The Société d’Anthropologie held yearly public lectures. In 1887, Royer gave two lectures about how minds evolve. She was already not feeling well, and after these talks, she rarely took part in the society's activities.

In 1891, she moved to a retirement home in Neuilly-sur-Seine. She lived there until she passed away in 1902.

Feminism and La Fronde

Royer went to the first International Congress on Woman's Rights in 1878, but she didn't speak. For the Congress in 1889, she was asked to lead the history section. In her speech, she argued that giving women the right to vote right away might make the church more powerful. She believed the first step should be to create non-religious education for women. Many French feminists at the time shared similar views. They worried that giving women the vote too soon might bring back the monarchy, which was closely linked to the conservative Catholic Church.

In 1897, when Marguerite Durand started the feminist newspaper La Fronde, Royer became a regular writer. She wrote articles about science and social topics. In the same year, her co-workers at the newspaper organized a special dinner in her honor, inviting many famous scientists.

Her book La Constitution du Monde, about the universe and how matter is made, was published in 1900. In it, she criticized scientists for focusing too much on small details and questioned accepted scientific theories. The scientific community didn't like the book much. One review said her ideas showed a "lamentable lack of scientific training and spirit." In the same year her book came out, she received the Légion d'honneur, a very high award in France.

Clémence Royer died in 1902 at the retirement home. Her son, René, passed away six months later in Indochina.

Images for kids

-

Photograph of Clémence Royer taken by Félix Nadar in 1865.

See also

In Spanish: Clémence Royer para niños

In Spanish: Clémence Royer para niños

| Dorothy Vaughan |

| Charles Henry Turner |

| Hildrus Poindexter |

| Henry Cecil McBay |