Community organizing facts for kids

Community organizing is when people who live near each other or share a problem work together. They form a group to help themselves and their community. It's about people coming together to make things better.

Unlike groups that focus on just building community, community organizers believe that real change often needs some friendly disagreement and effort. They want to create lasting power for their group. This way, the community can influence important decisions over time. For example, they might get a say before big plans are made. Organizers help new local leaders grow. They also help form groups and plan campaigns. A main goal is to build a strong, organized local democracy. This brings people together to fight for what the community needs.

Contents

- What is Community Organizing?

- How Neighborhood Groups Organize

- Grassroots Organizing: Starting from the Ground Up

- Feminist Community Organizing: Empowering Women

- Faith-Based Community Organizing: Churches and More

- Broad-Based Organizing: Many Groups Working Together

- Power vs. Protest: Making a Real Impact

- Political Views: Not Just One Side

- Fundraising: Finding Support

- What Community Organizing is NOT

- History of Community Organizing in the United States

- Community Organizing in the United Kingdom

- TCC (Trefnu Cymunedol Cymru / Together Creating Communities)

- The Community Organisers (CO) Programme (2011–2015)

- The Community Organisers Expansion Programme (COEP) (2017–2020)

- Community Organisers: Training and Support

- The National Academy of Community Organising

- London Citizens: Making a Difference in the Capital

- Citizens UK: Promoting Organizing Nationwide

- ACORN UK: Organizing for Housing Rights

- Living Rent: Scotland's Tenant Union

- Institute for Community Organising

- The Labour Party

- Community Organizing in Australia

- Community Organizing in Hong Kong

- Community Organizing for International Development

- See Also

What is Community Organizing?

Community organizers try to influence governments, companies, and other groups. They want to increase how much ordinary people are involved in making decisions. They also aim for wider social improvements. If talking doesn't work, these groups quickly tell others about the issues. They might put pressure on decision-makers. This can involve peaceful protests, boycotts, sit-ins, petitions, and getting involved in elections. Organizing groups often look for issues that will get people talking. This helps them attract and teach new members. It also builds commitment and shows they can help achieve local fairness.

Community organizers usually want to build groups that are fair and open to everyone. These groups care about the well-being of a specific group of people. A big goal is to help community members feel more powerful. This happens by working together to share power and resources more fairly. Organizers know that resources are not always shared equally in society. This can cause problems for communities. The process of becoming more powerful starts by seeing these differences. Even though they all want to empower communities, community organizing is understood in different ways.

There are several ways to do community organizing:

- Feminist organizing: This type focuses on women's issues. It sometimes uses a less confrontational approach.

- Faith-based community organizing (FBCO): This brings together religious groups. The Industrial Areas Foundation (IAF) was an early example. Groups like the Gamaliel Foundation and Faith in Action also use this method.

- Broad-based organizing: This grew from FBCO. It includes many types of groups, not just religious ones. Parts of the IAF started this trend.

- Neighborhood-based organizing: This organizes individuals or creates new groups from scratch.

How Neighborhood Groups Organize

- Doorknocking: Organizers go door-to-door to invite people to join. ACORN used this method a lot.

- Block-club organizing: People on a street block or in a building form a club. Tom Gaudette and Shel Trapp helped develop this. These clubs often connect to larger groups.

- House meetings: Many small meetings are held in homes. This leads to a bigger community meeting to form an organization. Fred Ross developed this. Cesar Chavez used a similar method for the United Farm Workers.

- "Organic" approach: Problems are found across a community. People organize around these local problems. Then leaders come together in a larger group. The Northwest Community Organization in Chicago is an example.

- Coalition building: Different groups join forces. People's Action (formerly National Peoples Action) is a good example.

These groups often focus on local issues. This is because they are about local problems and relationships between members.

Experts like Shane R. Brady and Mary Katherine O'Connor are trying to create a general model for community organizing. This model would connect the different types. For example, faith-based and many grassroots groups use the "social action approach." This comes from the work of Saul Alinsky. Feminist organizing uses a "community-building approach." This focuses on helping people understand their shared experiences to become stronger.

Grassroots Organizing: Starting from the Ground Up

Grassroots organizing starts from the very bottom. Organizers build community groups from scratch. They help new leaders emerge and organize people who haven't been involved before. This type of organizing is about people working together for their community and the common good.

Scholar Brian D. Christens says grassroots organizing focuses on building strong relationships between community members. These relationships help people learn to work together. They also learn to handle disagreements and get more involved in their community. Groups like National People's Action and ACORN use this method. Grassroots organizing is very popular in communities that face challenges, especially communities of color.

"Door-knocking" groups like ACORN organize people with lower incomes. They recruit members one by one. By going door-to-door, they reach people who might not be part of other groups or churches. Faith-based groups often organize more middle-class people. This is because their members usually come from larger churches. ACORN often stressed the need for constant action. This helped keep less connected members involved.

ACORN and other neighborhood groups were sometimes seen as more forceful than faith-based groups. This was partly because they needed to act often to keep their members engaged. Also, their local groups were sometimes more guided by staff organizers than by volunteer leaders. The "door-knocking" method takes more time. It also needs more organizers, who might be paid less and change jobs more often.

Unlike some other national groups, ACORN had a central plan for its local organizations. ACORN USA was a 501(c)4 organization. This meant it could be directly involved in election activities. However, donations to it were not tax-deductible.

Challenges for Grassroots Organizing

Grassroots organizing can be fragile. It often depends on support from more powerful people. Its goals can be easily stopped. Because it focuses on building relationships, some experts say it can be too passive. It might not always aim for a specific political or social goal. Building relationships doesn't always directly challenge big institutions. But it can change individual views through one-on-one talks.

Feminist Community Organizing: Empowering Women

Feminist organizing, also called women's community organizing, is about helping women. Its goals include:

- Getting more job opportunities for women.

- Improving women's physical and mental health.

- Helping women understand how their personal problems are linked to bigger societal unfairness.

Organizers want women to see these connections. While women have always been part of grassroots efforts, feminist organizing has its own special features.

Building Community in Feminist Organizing

Feminists want to break down barriers based on race and gender. They want to bring women together. Feminist organizing focuses on building relationships within the community. They see these connections as key to helping women understand their shared experiences. This is called the community-building approach. It's different from the social action approach, which focuses on challenging social and political unfairness.

The community-building approach needs both organizers and community members to work together. This removes power differences between them. It supports the idea that power comes from the community itself. Empowering the community means building that power. Experts like Catherine P. Bradshaw say feminist organizers believe power isn't something you can count. Instead, it's something you create. They also encourage community members to make decisions together, not just leaders.

To build relationships, feminist organizers encourage sharing personal stories. They believe this creates a feeling of connection and trust. This is very important in community organizing.

The shift to community building also happened because of outside reasons. In the 1980s, new economic ideas led many organizers to focus on community building.

Limitations of Feminist Organizing

Some feminists argue that this type of organizing can sometimes ignore the different backgrounds of women. When pushing for unity, feminist organizers might overlook the benefits of diversity. Economist Marilyn Power talks about the problem of hiding racial differences. Sociologist Akwugo Emejulu points out that focusing too much on stereotypes can limit how women are seen. Even though feminist organizers want to recognize women's diversity, some worry that the idea of unity can overshadow the reality of different experiences.

Studies suggest these limits might come from feminism's European roots. Historically, some European American feminists didn't fully value the racial differences among women. They also didn't always accept women who didn't fit traditional gender roles. Today, feminist organizing mainly focuses on gender inequalities. This means it might only address problems for women who are affected by these norms. This can be unhelpful for women who don't follow gender norms. Psychologist Lorraine Gutierrez says feminist organizing sometimes ignores bigger problems beyond gender norms. This can hurt women's empowerment because diversity is what often motivates women to act.

Faith-Based Community Organizing: Churches and More

Faith-based community organizing (FBCO) builds power and connections through groups like churches. Today, it mostly involves religious congregations. But it can also include unions, neighborhood groups, and other organizations. These groups come together based on shared values from their faith, not strict religious rules.

There are over 180 FBCOs in the U.S. and other countries. Local FBCO groups often connect through networks like the Industrial Areas Foundation, Gamaliel Foundation, and PICO National Network. In the U.S., the Bush administration even created a department to support faith-based organizing.

FBCOs tend to have mostly middle-class members. This is because the churches involved are often mainline Protestant and Catholic. Churches with mostly lower-income members usually don't join FBCOs. This is partly because they focus more on faith than on social action. FBCOs have started to include churches in wealthier areas. This helps them gain more power to fight unfairness.

Because FBCOs organize groups, they can reach many members with fewer organizers. These organizers are usually better paid and more professional. FBCOs focus on building a shared way of organizing and strong relationships between members. They are more stable than grassroots groups during quiet times. This is because their member churches continue to exist.

FBCOs are 501(c)3 organizations. Donations to them are tax-deductible. This means they can work on issues, but they cannot support specific political candidates.

Digital Changes in Faith-Based Organizing

Digital technology has greatly changed how faith-based groups organize. Authors Earl and Kimport (2011) show how it's now cheaper to "take action." This has opened up more chances for people to get involved in religious movements. Digital tools help faith groups share their message widely. They can also coordinate actions across distances and gather supporters like never before. This makes organizing more open to everyone. However, this digital shift also brings challenges for community identity and working together.

Broad-Based Organizing: Many Groups Working Together

Broad-based organizations purposefully include both non-religious and religious groups. Churches, synagogues, temples, and mosques join with public schools, non-profits, and labor unions. Organizations like the Industrial Areas Foundation are broad-based and funded by membership fees. These fees help them stay independent. They don't take government money and are not linked to any political party.

Broad-based groups teach leaders how to build trust across different races, faiths, and economic backgrounds. They do this through one-on-one meetings. Other goals include making member groups stronger. They help leaders develop new skills. They also create a way for ordinary families to be part of the political process. The Industrial Areas Foundation sees itself as a "university of public life." It teaches people about democracy.

Power vs. Protest: Making a Real Impact

Community organizing groups often use protests to make powerful groups listen. But protest is just one part of what they do. When groups show they have "power," they can often talk with and influence powerful people. This is backed by their history of successful campaigns. Just like unions represent workers, community organizing groups can represent communities.

This means community organizers can often get government officials or company leaders to talk. They don't always need to protest because of their reputation. As Saul Alinsky said, "power is not only what you have but what the enemy thinks you have." Building lasting "power" and influence is a main goal of community organizing.

"Rights-based" community organizing started in Pennsylvania in 2002. Community groups work to influence local governments to pass laws. These laws challenge state and federal rules that stop local governments from banning harmful corporate activities. The laws are written to protect the rights of "human and natural communities." They also reject the idea of "corporate personhood" and "corporate rights." Since 2006, they have also included rights for "natural communities and ecosystems."

This type of organizing focuses on local laws. But the real goal is to show that local power can protect community rights. It also aims to show when power is used to help corporations instead of people. So, passing these local laws is an organizing strategy, not just a legal one. Courts often say that local governments can't make laws that go against state and federal laws. But when companies or governments try to overturn these local laws, they have to argue against the community's right to make decisions about local issues that affect them.

The first rights-based local laws stopped companies from taking over farming and banned corporate waste dumping. More recent efforts have banned corporate mining, large water withdrawals, and chemical pollution. For example, Denton, Texas, tried to stop fracking. It worked at first, but then the ban was overturned. New laws were passed to stop other Texas communities from doing similar bans.

Political Views: Not Just One Side

Community organizing isn't only for progressive politics. Many conservative groups, like the Christian Coalition of America, also do it. However, the term "community organizing" usually refers to more progressive groups. This was clear during the 2008 U.S. presidential election. Republicans and conservatives reacted strongly against the idea of community organizing.

Fundraising: Finding Support

Organizing groups often struggle to find money. They rarely get government funding because their work often challenges government policies. Foundations that usually fund service activities often don't understand organizing groups. Or they avoid their more confrontational methods. Progressive and centrist organizing groups usually have low- or middle-income members. So, they can't always support themselves through membership fees.

In the past, some groups accepted money for direct services. But this often led them to stop their organizing work. This was because their organizing efforts could threaten funding for their "service" parts.

Recent studies show that funding community organizing can bring big benefits. For example, one study found $512 in community benefits for every $1 of funding. This comes from new laws and agreements with companies. This doesn't even include other non-money achievements.

What Community Organizing is NOT

To understand what community organizing is, it helps to know what it is not.

- Activism: This is different if activists protest without a clear plan to build power or make specific changes.

- Mobilizing: People "mobilize" for a specific change but don't have a long-term plan. These groups often break up after the campaign ends.

- Advocacy: Advocates usually speak for others who are seen as unable to speak for themselves. Community organizing wants those affected to speak for themselves.

- Social movement building: A big social movement includes many activists, groups, and spokespeople. They share common goals but not a common structure. An organizing group might be part of a movement. Movements often end when their main issues are addressed.

- Legal action: Lawyers are important. But if a plan is mostly about a lawsuit, it can push grassroots efforts aside. This can stop people from building shared power. However, organizing groups and legal strategies can work well together.

- Direct service: Many people think helping others directly is civic engagement. But organizing groups usually avoid providing services today. History shows that when they do, organizing for shared power often gets left behind. Powerful groups sometimes threaten the "service" parts of organizing groups to stop collective action.

- Community development: This is about improving communities through different plans. It's usually led by professionals in government or non-profit groups. Community development often assumes groups can work together without much conflict. One popular form is asset-based community development. This looks for existing strengths in a community. While there are similarities, community organizing is different because it focuses on power struggles.

- Nonpartisan dialogues about community problems: These efforts create chances for people to talk about problems. Like organizing, they aim to be open to different ideas. But organizing groups focus on creating a single "voice" to gain power and resources for their members.

- Coercion: The power gained in community organizing is not forced. It's not like the power of banks or governments. Instead, it uses the voluntary efforts of community members working together. The benefits often help everyone in similar situations, not just group members. For example, workers might benefit from a campaign that affects their industry.

History of Community Organizing in the United States

The history of community organizing in the U.S. can be divided into four main periods:

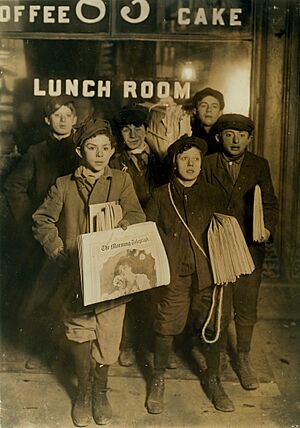

1880 to 1900: Early Efforts

During this time, people tried to help immigrant neighborhoods in cities. This was due to fast immigration and industrial growth. Reformers focused on building community through settlement houses and other services. This approach was like social work. The Newsboys Strike of 1899 was an early example of young people leading organizing efforts.

1900 to 1940: Social Work and New Ideas

Much of the organizing methods came from Schools of Social Work. They were based on the ideas of John Dewey, who focused on experience and education. Many people who criticized capitalism were also active. Studs Terkel wrote about community organizing during the Great Depression. Most groups focused on national issues. This was because the country's economic problems seemed too big for local changes.

1940 to 1960: Saul Alinsky and the Idea of "Community Organizer"

Saul Alinsky, from Chicago, is often credited with coining the term community organizer. He wrote Reveille for Radicals (1946) and Rules for Radicals (1971). These books were the first to clearly explain the strategies and goals of community organizing in America.

Alinsky's ideas were strong and direct:

- A People's Organization is a conflict group... Its only reason for existing is to fight against all the bad things that cause suffering...

- A People's Organization is dedicated to an endless war. It's a war against poverty, sadness, crime, sickness, unfairness, hopelessness, and unhappiness...

- A People's Organization lives in a world of tough reality... full of struggles, strong feelings, and confusion...

In 1940, Alinsky started the Industrial Areas Foundation (IAF). He had support from a Catholic Bishop and a newspaper publisher. The IAF aimed to work with religious groups and civic organizations. They wanted to build "broad-based organizations" to train local leaders and build trust.

After Alinsky died in 1972, Edward T. Chambers took over the IAF. Many professional organizers and leaders have been trained there. Fred Ross, who worked with Alinsky, mentored Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta. Other groups like PICO National Network and Gamaliel Foundation followed the IAF's lead.

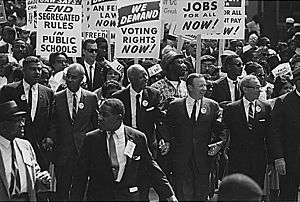

1960 to Present: New Movements and Professional Growth

In the 1960s, the New Left tried community organizing. They felt Alinsky's local work was too limited. But they found that to be trusted, they needed to get results from local power structures. By the 1970s, many New Left groups had closed their offices.

Still, the Civil Rights Movement, anti-war protests, women's liberation, and the fight for gay rights all used ideas from neighborhood organizing. Experiences with government anti-poverty programs led to new ideas in the 1970s. These ideas shaped activities and groups for the rest of the century. Also, local clubs were formed to build community spirit and social connections.

Changes in Urban Communities

Over these decades, many middle-class white Americans moved out of mostly Black areas. Community organizations also became more professional, often becoming 501(c)3 non-profits. These changes meant that the strong ethnic and racial communities in cities started to fade. So, community organizers began to focus on creating community. They worked to build relationships between members. While Alinsky had worked with churches, these trends led to more focus on organizing through congregations in the 1980s. This was because churches were some of the few broad-based community groups left. This shift also led to more focus on religion, faith, and social struggles.

Rise of National Support Organizations

Several groups were founded to train and support national coalitions of local community organizing groups. Many of these were faith-based. The Industrial Areas Foundation was the first. Other key groups include ACORN, PICO National Network, and the Gamaliel Foundation. The role of the organizer became more professional. Efforts were made to make organizing a long-term career. These national "umbrella" groups help local volunteer leaders learn a common "language" about organizing. They also help organizers improve their skills.

Famous Community Organizers

Many important leaders in community organizing today came from the National Welfare Rights Organization. These include John Calkins of DART and Wade Rathke of ACORN.

Other famous community organizers over the years include: Ella Baker, Heather Booth, César Chávez, Lois Gibbs, Martin Luther King Jr., Ralph Nader, Barack Obama, and Paul Wellstone.

Youth Organizing

More recently, youth organizing groups have appeared across the country. These groups use similar strategies to Alinsky's. They also often provide social and sometimes material support to young people who face challenges. Most of these groups are created and led by young people or former youth organizers.

The 2008 Presidential Election

Before becoming President, Barack Obama worked as an organizer for a Gamaliel Foundation faith-based group in Chicago. Marshall Ganz, who worked with César Chávez, used community organizing methods for Obama's 2008 presidential campaign.

At the 2008 Republican National Convention, former New York City mayor Rudolph Giuliani questioned Obama's role as a community organizer. He asked, "What does a community organizer actually do?" The crowd cheered. The vice presidential candidate, Alaska governor Sarah Palin, also said her experience as mayor was "sort of like being a community organizer, except that you have actual responsibilities." In response, some progressives said, "Jesus was a community organizer, Pontius Pilate was a governor." This phrase appeared on bumper stickers. Pontius Pilate was the Roman official who ordered Jesus's execution.

After Obama's election, his campaign group became "Organizing for America." It was placed under the Democratic National Committee (DNC). Organizing for America worked to support the president's plans, like the Affordable Health Care Act.

After the 2012 election, Organizing for America changed again. It is now called Organizing for Action. This group trains people to be community organizers. It works on local and national issues like climate change, immigration, and marriage equality.

Community Organizing in the United Kingdom

TCC (Trefnu Cymunedol Cymru / Together Creating Communities)

TCC (Trefnu Cymunedol Cymru / Together Creating Communities) is the oldest community organizing group in the UK. It started in 1995. TCC is a membership organization. Its members include community groups, faith groups, and schools in North East Wales. As a broad-based alliance, TCC brings communities together to act on local, regional, and national issues.

TCC is special because it works in a diverse area, including many rural places, not just cities.

TCC has had many successful campaigns over 25 years. These include:

- Getting employers (like the Welsh Assembly) to pay the Living Wage.

- Improving access to leisure facilities for Muslim women.

- Making Wales the world's first Fairtrade nation.

- Improving British Sign Language for Deaf young people.

- Getting a Parkinson's nurse for North East Wales.

- Getting a local authority to recycle instead of building an incinerator.

- Getting a homeless shelter for Wrexham.

In 2019, TCC's Stop School Hunger campaign led the Welsh Government to fund breakfast and lunch for the poorest students.

TCC offers ongoing training for adults and young people in community organizing. Leaders from TCC's diverse members work together to be active in democracy. They hold regular meetings with powerful people before elections and build relationships with them.

The Community Organisers (CO) Programme (2011–2015)

In 2010, the UK government promised to train a new generation of Community Organisers. This was part of its "Big Society" plan. The goal was to give communities more power over their neighborhoods and services.

An evaluation of the CO program started in 2012. The final report in December 2015 summarized its findings.

The Community Organisers Expansion Programme (COEP) (2017–2020)

In March 2017, Community Organisers received a large contract to grow its movement. The goal was to increase the number of Community Organisers from 6,500 to 10,000 by 2020.

This program helps make community organizing a part of neighborhoods across England. It teaches local people skills to improve their communities. It also includes young people from the National Citizen Service (NCS). The program created the National Academy of Community Organising to keep training new organizers.

Community Organisers: Training and Support

A key goal of the CO program was to create an independent group to support community organizing in England. Established in 2015, Community Organisers is now the national training and membership body. It offers certified training. It also set up the National Academy of Community Organising to provide training and support in the UK.

The National Academy of Community Organising

The National Academy of Community Organising (NACO) provides certified training and courses in community organizing. It is a network of local centers called Social Action Hubs. These organizations deliver the courses.

There are currently 22 Social Action Hubs across England. They are local groups committed to community organizing. They train and support people to understand and practice community organizing. They also help people get involved in social action.

Each Social Action Hub is unique. But all are approved by Community Organisers to offer their training courses.

London Citizens: Making a Difference in the Capital

London Citizens started in East London in 1996 as TELCO. It later grew to include South, West, and North London. London Citizens has over 160 member groups, including schools, churches, mosques, unions, and volunteer organizations.

At first, they worked on small issues, like stopping a factory from polluting the air. Over time, they took on bigger campaigns. Before the London mayoral elections, they held large meetings with mayoral candidates. They asked candidates to support issues like the London Living Wage, help for undocumented migrants, safer cities, and community housing. South London Citizens investigated how a government department treated refugees. This led to a new visitor center being built.

Citizens UK: Promoting Organizing Nationwide

Citizens UK has been promoting community organizing in the UK since 1989. It has helped establish community organizing as a profession. Neil Jameson, the executive director, founded the organization after training in the USA. Citizens UK has set up groups in cities like Liverpool, Sheffield, and Bristol. London Citizens' early group, TELCO, formed in 1996.

Citizens UK General Election Assembly

In May 2010, Citizens UK held a big meeting before the General Election. Leaders from the three main political parties attended. They were asked if they would work with Citizens UK if elected. Each leader promised to work with the group. They agreed to support the Living Wage and stop holding children of refugee families in detention.

Living Wage: Fair Pay for All

In 1994, Baltimore, USA, passed the first living wage law. This improved conditions for low-wage workers. In London, London Citizens launched a campaign in 2001. The Living Wage Campaign asks for every worker to earn enough to support their family. By 2010, over 100 employers were paying the Living Wage. This helped 6,500 families escape working poverty.

The Living Wage is an hourly rate calculated each year based on the cost of living. It's the minimum pay needed to provide for a family. London's rate in 2010–11 was £7.85 per hour. Other UK cities are now following London's example. Citizens UK set up the Living Wage Foundation in 2011. It provides information and certifies companies. It also sets the Living Wage rate outside London.

People's Olympic Legacy: Benefits for Londoners

When London bid to host the 2012 Olympic Games, London Citizens used its power. They wanted to ensure the billions spent would leave a lasting benefit for Londoners. In 2004, London Citizens signed an agreement with the London 2012 bid team. This agreement promised specific benefits for East Londoners.

The "People's Promises" included:

- 2012 affordable homes for local people.

- Money from the Olympic development for local schools and health services.

- The University of East London to benefit from the sports legacy.

- At least £2 million for a Construction Academy to train local people.

- At least 30% of jobs for local people.

- The Lower Lea Valley to be a 'Living Wage Zone' with all jobs paying a living wage.

The Olympic organizers work with London Citizens to deliver these promises.

Independent Asylum Commission

Citizens UK set up the Independent Asylum Commission. This group looked into concerns about how refugees and asylum seekers were treated. Its report made over 200 suggestions for change. This led to the government ending the practice of holding children of refugee families in detention in 2010.

ACORN UK: Organizing for Housing Rights

ACORN UK started in Easton, Bristol, in May 2014. It began with 100 tenants and 3 staff organizers. They wanted more secure, better quality, and more affordable housing. Two of the founders had been trained by the Community Organisers programme.

ACORN UK has since grown, hiring more staff and opening branches in Newcastle and Sheffield. It has 15,000 members. ACORN UK uses online organizing through social media along with its traditional door-knocking approach. This helps them organize private renters who move often.

The group also combines local "member defense" actions (like resisting evictions and protesting bad landlords) with bigger campaigns for housing rights. For example, they got local government support for their "ethical lettings charter." They also convinced Santander bank to remove a mortgage rule that forced landlords to raise rents. They worked with another group to register and encourage renters to vote in the 2016 election.

Living Rent: Scotland's Tenant Union

Living Rent is Scotland's tenant union. It is also linked to ACORN International. The group formed in 2015 and now has branches in Glasgow and Edinburgh. It has two organizing staff members.

Institute for Community Organising

Citizens UK set up the Institute for Community Organising (ICO) in 2010. The ICO offers training for people who want to be full-time or part-time community organizers. It also trains community leaders. The Institute provides training and advice to other groups that want to use community organizing methods. It has an Academic Advisory Board and an International Professional Advisory Body.

The Labour Party

In 2018, The Labour Party in the UK created a Community Organising Unit. This unit focuses on working with communities and employee groups. It helps them campaign on local and workplace issues.

Community Organizing in Australia

Since 2000, there has been a lot of talk about community organizing in Sydney. A community organizing school was held in 2005. It included unions, community groups, and religious organizations. In 2007, Amanda Tattersall, an organizer, asked Unions NSW to support a new group called the Sydney Alliance. This group started on September 15, 2011, with 43 organizations. It is helping to set up other community organizing groups across Australia.

Community Organizing in Hong Kong

The Start of Organizing in the 1970s

After riots in Hong Kong in 1966 and 1967, the British government started new policies. One was the "Neighbourhood Level Community Development Project" (NLCDP) in 1978. This was meant to manage activist groups. Social workers were hired to run activities and encourage involvement in areas needing welfare services. Some experts believe that, against the government's wishes, NLCDP became a place for "radical community organizing movements" that used protests.

The 1970s saw many social and activist groups form in Hong Kong. Many groups started without government money, which gave them more freedom. Some were formed by progressive Christians. For example, the Society for Community Organization (SoCO) started in 1971. Pastors from different churches in Tsuen Wan discussed local issues. They got money from the World Council of Churches to form the Tsuen Wan Ecumenical Social Service Centre (TWESSC) in 1973 to help low-income people.

Residents organized movements about housing. They asked for better facilities and changes to housing policies. One example is the protest of the Yau Ma Tei boat people.

Saul Alinsky's Influence in Hong Kong

The Asia Committee for People's Organisation (ACPO) was influenced by Liberation theology and Saul Alinsky's ideas. It gave money and training to church groups in Asia, including Hong Kong. They invited Alinsky-trained experts to lead training programs. Alinsky himself visited Hong Kong in 1971. His books, Reveille for Radicals and Rules for Radicals, were widely read by students and social workers. Because of Alinsky, social workers started using more direct and challenging methods to make the government act.

Community Organizing in the 1990s

In the 1990s, some social movements in Hong Kong used community organizing to demand housing rights. These caused a lot of discussion, especially among social workers.

In 1993, the TWESSC organized public housing residents to protest. They wanted the British government to stop policies that raised rent for higher-income residents. They marched towards the Governor's House but were stopped. They then sat down on the road, blocking traffic. They demanded the Governor accept their petition. As a result, 23 people were arrested.

In 1994, the Buildings Department started tearing down rooftop houses. These were seen as illegal buildings. On October 17, social workers from TWESSC organized rooftop residents to protest. They asked for new homes. After staying overnight outside a government building, they sat in the lobby. They kept all the elevators open, demanding to meet the Director of Buildings. On December 14, social workers organized residents to sit on a road outside the building. Residents brought everyday items like empty gas pots and cooking tools. They wanted to show they were losing their homes. The gas pots became the reason for police to clear the protest. This caused a lot of controversy. Twenty-two people, including social workers, were arrested for blocking traffic.

In 1995, rooftop residents in Mong Kok protested against plans to tear down their homes. The group SoCO, a student organization, and other citizens formed "Kingland's friends" to support them. In March, about 20 residents and social workers protested outside a government office. Three were said to have clashed with police and security guards and were arrested. In late April, SoCO decided to stop supporting "Kingland's friends." They said residents were being influenced by students to plan illegal protests. In May, nearly 300 police officers cleared the Kingland Apartments.

These events affected how community organizing was done in social work. SoCO complained to TWESSC that some of their social workers joined "Kingland's Friends" and interfered with SoCO's work. The leaders and staff of TWESSC disagreed about social workers' roles in social movements. This led to six workers being dismissed. TWESSC was closed in January 1997.

In 1995, the government announced plans to eventually stop NLCDPs. On July 1, 1997, Hong Kong became part of mainland China. The new government changed how it funded social work. This is seen by some as a way to make social work less political. As a result, "radical community organizing" by social workers became less common.

Community Organizing for International Development

One of Alinsky's friends, Herbert White, became a missionary in South Korea and the Philippines. He brought Alinsky's ideas and books with him. In the 1970s, he helped start a community organization in a poor area of Manila. The ideas of community organizing spread through many local non-profit groups and activists in the Philippines.

Filipino organizers combined Alinsky's ideas with liberation theology (a pro-poor religious movement) and the ideas of Brazilian educator Paulo Freire. They found community organizing to be a good way to work with the poor during the time of dictator Ferdinand Marcos. Unlike communist fighters, community organizers quietly encouraged people to think critically about their situation. They helped people organize and solve real problems together. Community organizing helped prepare the way for the People Power Revolution of 1986. This peaceful movement pushed Marcos out of power.

The ideas of community organizing are now used by many international organizations. It's a way to encourage communities to be involved in social, economic, and political change in developing countries. This is often called participatory development or capacity building. Robert Chambers has been a strong supporter of these methods.

In 2004, members of ACORN created ACORN International. This group has since started organizations and campaigns in Peru, India, Canada, Kenya, Argentina, and other countries.

See Also

- Category:Community activists

- Communitarianism

- Community education

- Community film

- Community practice

- Community psychology

- Critical consciousness

- Critical psychology

- Homeowner association

- Humanism

- Large-group capacitation

- Organization workshop

- Political machine

- Union organizer