Paulo Freire facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Paulo Freire

|

|

|---|---|

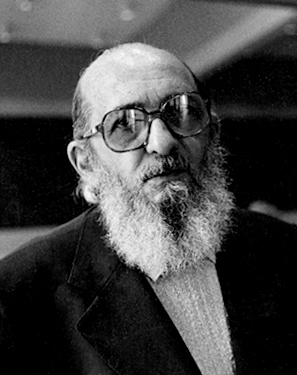

Freire in 1977

|

|

| Born |

Paulo Reglus Neves Freire

19 September 1921 Recife, Pernambuco, Brazil

|

| Died | 2 May 1997 (aged 75) |

| Political party | Workers' Party |

| Spouse(s) |

|

| Academic background | |

| Alma mater | University of Recife |

| Influences |

|

| Academic work | |

| Discipline | |

| School or tradition |

|

| Doctoral students | Mario Sergio Cortella |

| Notable works | Pedagogy of the Oppressed (1968) |

| Notable ideas |

|

| Influenced |

Fazle Hasan Abed

Marcella Althaus-Reid Stanley Aronowitz Christine Ballengee-Morris Ana Mae Barbosa Steve Biko Augusto Boal Leonardo Boff Francisco Brennand Fernando Cardenal Enrique Martinez Celaya Vicky Colbert James H. Cone Antonia Darder Mestre Ferradura Ramón Flecha Moacir Gadotti Henry Giroux Cees Hamelink bell hooks Didacus Jules Karen Keifer-Boyd Joe L. Kincheloe James D. Kirylo Jonathan Kozol Khen Lampert Colin Lankshear Allan Luke Donaldo Macedo Ignacio Martín-Baró Peter Mayo Alan McCombes Peter McLaren Jack Mezirow Oscar Mogollon G. Nammalvar Gino Piccio Majid Rahnema Howard Richards Marshall Rosenberg Ira Shor Shirley R. Steinberg Carlos Alberto Torres María Guillermina Valdes Villalva Cornel West |

Paulo Reglus Neves Freire (19 September 1921 – 2 May 1997) was a Brazilian educator and philosopher. He was a strong supporter of critical pedagogy. This is a way of teaching that encourages students to think deeply about the world. His famous book, Pedagogy of the Oppressed, is a key text in this field. It was one of the most referenced books in social studies around 2016.

Contents

Who Was Paulo Freire?

Paulo Freire was born on September 19, 1921. His family lived in Recife, Brazil. He grew up during the Great Depression. This was a time when many people faced poverty and hunger. Because of this, Freire understood what it was like to be poor.

In 1931, his family moved to a cheaper city. His father passed away in 1934. Freire fell behind in school for four years. He spent a lot of time playing football with other kids. He said he learned a lot from these experiences. These early years shaped his ideas about helping people. He realized that poverty made it hard for him to learn. He decided to dedicate his life to improving education for the poor.

Freire's Education and Early Career

In 1943, Freire went to law school at the University of Recife. He also studied philosophy and the psychology of language. Even though he could practice law, he chose to become a secondary school Portuguese teacher.

In 1944, he married Elza Maia Costa de Oliveira. She was also a teacher. They worked together and had five children.

In 1946, Freire became the director of education in Pernambuco. He worked with adults who could not read or write. He started to develop his special way of teaching. This method later influenced a movement called liberation theology. In Brazil during the 1940s, being able to read was necessary to vote.

In 1961, he became a director at the University of Recife. In 1962, he got a chance to try his ideas on a large scale. Three hundred sugarcane workers learned to read and write in just 45 days. This success led the Brazilian government to create many "cultural circles" across the country. These circles were places where people could learn.

Challenges and Exile

In 1964, a new military government took over Brazil. They stopped Freire's education programs. Freire was arrested and held for 70 days. He was accused of being a traitor. After his release, he went to Bolivia for a short time. Then he moved to Chile, where he worked for five years.

In 1967, Freire published his first book, Education as the Practice of Freedom. His most famous book, Pedagogy of the Oppressed, came out in 1968.

His work became well-known around the world. In 1969, he was invited to be a visiting professor at Harvard University. The next year, Pedagogy of the Oppressed was published in Spanish and English. This helped his ideas spread even further. Because of political disagreements, his book was not published in Brazil until 1974.

After his time at Harvard, Freire moved to Geneva. He worked as an education advisor for the World Council of Churches. He helped with education reforms in former Portuguese colonies in Africa. These included Guinea-Bissau and Mozambique.

Return to Brazil and Later Life

In 1979, Freire visited Brazil for the first time in over ten years. He moved back permanently in 1980. He joined the Workers' Party in São Paulo. He supervised their adult literacy project from 1980 to 1986.

When the Workers' Party won the 1988 São Paulo mayoral elections in 1988, Freire became the municipal Secretary of Education. He continued to work for better education.

Paulo Freire passed away on May 2, 1997, in São Paulo. He died from heart failure.

What Was Freire's Teaching Style?

Paulo Freire developed a unique way of thinking about education. It combined older ideas from thinkers like Plato with newer ideas. These newer ideas came from Marxist and anti-colonialist thinkers. His book Pedagogy of the Oppressed (1968) built on ideas from Frantz Fanon's The Wretched of the Earth. Fanon believed that colonized people needed a new kind of education. It should be modern and help them break free from colonial ways of thinking.

In Pedagogy of the Oppressed, Freire talked about the difference between "oppressors" and "oppressed." He believed education should help oppressed people regain their dignity. It should help them overcome their difficult situations. But he also said that people must be active in their own freedom.

He also believed that those in power must be willing to change. They need to understand their role in keeping others down. Only then can true freedom happen. Freire said, "Those who truly care for people must always examine themselves."

Freire thought that education and politics are always connected. He saw teaching and learning as political actions. Teachers and students need to understand the political ideas behind education. The way students are taught and what they learn often serves a political purpose. Teachers also bring their own political views into the classroom. This connection is a main idea of critical pedagogy.

Why Did Freire Criticize the "Banking Model" of Education?

Freire is famous for criticizing what he called the "banking model" of education. In this model, students are seen as empty banks. Teachers simply deposit information into them. Freire said this way of teaching "turns students into receiving objects." It tries to control how they think and act. This makes people just accept the world as it is. It stops them from being creative.

This idea was not completely new. Thinkers like Jean-Jacques Rousseau believed children were active learners. They were not just empty slates waiting to be filled. John Dewey also criticized simply giving facts as the goal of education. Dewey saw education as a way to create social change. Freire's work brought these ideas back. He connected them to modern teaching methods. This helped create the field known as critical pedagogy.

What is the "Culture of Silence"?

Freire believed that unfair social situations create a "culture of silence." This makes oppressed people feel negative and powerless. They might feel like they are not good enough. Learners need to develop a critical consciousness to understand this. They need to see that this "culture of silence" is made to keep them down.

A "culture of silence" can also make people lose their ability to question things. They might not be able to think critically about the culture forced on them. Freire thought that social class and race are part of the traditional education system. This system can take away "ways of thinking that lead to a language of critique." This means it stops people from questioning and speaking out.

See also

In Spanish: Paulo Freire para niños

In Spanish: Paulo Freire para niños

- Adult education

- Michael Apple

- John Asimakopoulos

- Clodomir Santos de Morais

- Dialogic education

- Dialogic learning

- Dialogic pedagogy

- Raya Dunayevskaya

- Education in Brazil

- Lewis Gordon

- James D. Kirylo

- Landless Workers' Movement

- Marxist humanism

- Paulo Freire University

- Peer mentoring

- Popular education

- Praxis intervention

- Problem-posing education

- Rouge Forum

- Second Episcopal Conference of Latin America

- Structure and agency

| George Robert Carruthers |

| Patricia Bath |

| Jan Ernst Matzeliger |

| Alexander Miles |