Compressed tea facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Compressed tea |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese name | |||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 緊壓茶 | ||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 紧压茶 | ||||||||

| Literal meaning | tight press tea | ||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||

| Hangul | 고형차 | ||||||||

| Hanja | 固形茶 | ||||||||

| Literal meaning | solid tea | ||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||

| Kanji | 緊圧茶 | ||||||||

| Kana | きんあつちゃ | ||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Tea brick | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese name | |||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 磚茶 | ||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 砖茶 | ||||||||

| Literal meaning | brick tea | ||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||

| Hangul | 벽돌차 / 전차 | ||||||||

| Hanja | 甓-茶 / 磚茶 | ||||||||

| Literal meaning | brick tea | ||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||

| Kanji | 磚茶 | ||||||||

| Kana | ひちゃ、とうちゃ、せんちゃ | ||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Tea cake | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese name | |||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 餅茶 | ||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 饼茶 | ||||||||

| Literal meaning | cake tea | ||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||

| Hangul | 떡차 / 병차 | ||||||||

| Hanja | -茶 / 餠茶 | ||||||||

| Literal meaning | cake tea | ||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||

| Kanji | 餅茶 | ||||||||

| Kana | へいちゃ、もちちゃ | ||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Tea lump | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese name | |||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 團茶 | ||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 团茶 | ||||||||

| Literal meaning | lump tea | ||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||

| Hangul | 덩이차 / 단차 | ||||||||

| Hanja | --茶 / 團茶 | ||||||||

| Literal meaning | lump tea | ||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||

| Kanji | 団茶 | ||||||||

| Kana | だんちゃ | ||||||||

|

|||||||||

Compressed tea is tea that has been pressed into solid shapes. These shapes can be called tea bricks, tea cakes, or tea lumps. They are made from whole or finely ground tea leaves. These leaves can be black tea, green tea, or post-fermented tea.

In ancient China, compressed tea was the most common way to prepare tea. This was especially true before the Ming dynasty. Even today, many pu-erh teas are sold in pressed forms. People can drink compressed tea or even eat it. Long ago, it was also used as a type of money!

Contents

How Is Compressed Tea Made?

In ancient China, compressed teas were often made from dried and ground tea leaves. These leaves were pressed into bricks or other shapes. Sometimes, whole or partly dried leaves were used too.

Tea bricks were very popular for trade before the 1800s in Asia. They were smaller and easier to carry than loose tea leaves. This made them perfect for long journeys by caravans on routes like the Ancient tea route. They were also less likely to get damaged during travel.

Modern Tea Production

Today, compressed teas are still made for drinking, like pu-erh teas. They are also sold as souvenirs. Most modern compressed teas are made from whole leaves.

Compressed tea comes in many traditional shapes:

- A dome-shaped piece, usually 100g, is called tuóchá (沱茶). It can mean "bird's nest tea" or "bowl tea."

- A small dome-shaped piece, about 3g–5g, is called xiǎo tuóchá (小沱茶). This means "small tuóchá." It's just enough for one pot or cup of tea.

- A larger disc, around 357g, is called bǐngchá (饼茶). This means "biscuit tea" or "cake tea."

- A large, flat, square brick is called fāngchá (方茶). This means "square tea."

The Pressing Process

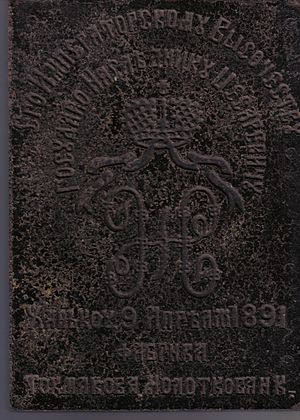

To make a tea brick, tea leaves are first steamed. Then, they are put into a press. The press squeezes them into a solid block. Sometimes, the press leaves a design on the tea. This could be an artistic pattern or the texture of the cloth used to press it.

If the tea is made from powder, it might be moistened with rice water. This helps the powder stick together. After pressing, the tea blocks are left to dry. They stay in storage until they have lost enough moisture.

Tea Transport in the Past

The city of Ya'an was a major center for a special kind of tea. This tea was sent in large amounts to Tibet through places like Kangding. Even though Chinese people thought this tea was not the best, Tibetans loved its strong flavor. It mixed well with the yak butter they added to their tea.

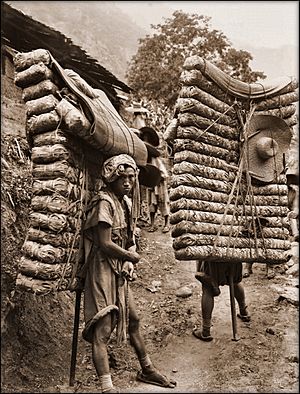

This "brick tea" included not just tea leaves, but also coarser leaves and twigs. It sometimes had leaves and fruit from other plants too. This mix was steamed, weighed, and pressed into hard bricks. These bricks were then wrapped in matting. Each package weighed about 22 to 26 pounds. Workers called coolies carried these heavy loads to Kangting.

In Kangting, the tea bricks were repacked for animal transport. They were cut in half and then grouped into sets of three. Tea meant for faraway places like Lhasa was sewn into yak hides. These hides were dried in the sun, not tanned. When used for packing, they were soaked to make them soft. Then, they were sewn tightly around the tea. Once dry, the tea was protected by a container as hard as wood. This kept the tea safe from rain, bumps, or even falling into streams.

Women tea coolies in Kangting had a special job. They moved the tea from warehouses to inns where caravans started. They were very strong and could carry a full yak's load several times a day.

How Is Compressed Tea Used?

Because tea bricks are so dense and tough, people usually break them into small pieces and boil them. In the past, during the Tang Dynasty, people would grind them into a fine powder. You can still see this tradition in modern Japanese tea powders. Also, the lei cha (擂茶) eaten by the Hakka people uses powdered tea leaves.

Drinking Compressed Tea

In ancient China, making a drink from tea bricks involved three steps:

- Toasting: First, a piece of the tea brick was broken off and often toasted over a fire. This helped clean the tea and remove any mold or bugs. Toasting also gave the tea a nice flavor.

- Grinding: The toasted tea was then broken up and ground into a fine powder.

- Whisking: Finally, the powdered tea was mixed into hot water and frothed with a whisk. People enjoyed the colors and patterns of the tea as they drank it.

Today, people usually just break off pieces of pu-erh tea bricks. They rinse the pieces well and then steep them directly in hot water. The old way of toasting, grinding, and whisking is not common anymore.

In Korea, Tteokcha (Korean: 떡차; lit. "cake tea") was the most common type of tea. It was also called byeongcha (Korean: 병차; Hanja: 餠茶; lit. "cake tea"). Pressed tea shaped like yeopjeon (coins with holes) was called doncha (Korean: 돈차; lit. "money tea"). Borim-cha (Korean: 보림차; Hanja: 寶林茶) is a popular tteokcha from the Borim temple in Jangheung County.

Eating Compressed Tea

In parts of Central Asia and Tibet, people have eaten tea bricks for a long time. In Tibet, pieces of tea are broken off and boiled overnight in water, sometimes with salt. This strong tea is then mixed with butter, cream, or milk and a little salt to make butter tea. This is a very important food in Tibetan cooking.

Tea mixed with tsampa (roasted barley flour) is called Pah. People knead small amounts of this mixture into balls and eat them. In some parts of Japan, people eat a similar food. They mix strong tea with grain flour.

In parts of Mongolia and Central Asia, people directly eat a mix of ground tea bricks, grain flours, and boiling water. Eating the whole tea can provide important fiber that might be missing from their diet.

Tea as Money

Because tea was so valuable in many parts of Asia, tea bricks were used as a form of money. This happened in China, Tibet, Mongolia, and Central Asia. It was similar to how salt bricks were used as money in parts of Africa.

Tea bricks were even preferred over metal coins by nomads in Mongolia and Siberia. This is because the tea could be used as money, eaten as food if someone was hungry, or brewed as a medicine for coughs and colds. Tea bricks were still used as edible money in Siberia until World War II.

Tea bricks for Tibet were mostly made in Ya'an in Sichuan province. They came in five different qualities, and their value changed based on the quality. The most common type of tea brick used as money in the late 1800s and early 1900s was the third quality. Tibetans called it "brgyad pa," meaning "eighth." This was because it was once worth eight Tibetan tangkas (a silver coin) in Lhasa. These standard bricks were also traded from Tibet to Bhutan and Ladakh.

See also

In Spanish: Ladrillo de té para niños

In Spanish: Ladrillo de té para niños

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |