Coventry Blitz facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Coventry Blitz |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Strategic bombing campaign of World War II | |||||||

Winston Churchill, the Mayor J. A. Moseley, the Bishop of Coventry M. G. Haigh, the Deputy Mayor A. R. Grindlay, and others visiting the ruins of Coventry Cathedral in September 1941 |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

The Coventry Blitz was a series of heavy bombing attacks on the British city of Coventry. These attacks happened during World War II. The German Air Force, known as the Luftwaffe, bombed the city many times. The word "Blitz" comes from the German word Blitzkrieg, meaning "lightning war." The most damaging attack took place on the night of 14 November 1940 and lasted until the morning of 15 November.

Contents

Why Coventry Was a Target

At the start of World War II, Coventry was a busy industrial city. About 238,000 people lived there. Like many cities in the West Midlands, it had many factories. These factories made things from metal and wood.

Coventry was especially important for making cars, bicycles, and airplane engines. After 1900, it also started making munitions (military supplies like bombs and bullets). Because of this, Coventry was a fair target for bombing during the war.

During First World War, Coventry's factories were very good at making tools. This meant they could quickly switch to making war supplies. The Coventry Ordnance Works became a top center for making munitions. It produced 25% of all British aircraft during that war.

Many of Coventry's factories were mixed in with homes and shops in the city center. However, new housing areas built between the wars were usually separate from the industrial parts. Even though many car factories were in Coventry, they had changed to help with the war effort.

Air Raids on Coventry

Early Attacks in 1940

Between August and October 1940, the Luftwaffe launched 17 smaller raids on Coventry. These happened during the Battle of Britain. About 198 tons of bombs were dropped. These early attacks killed 176 people and injured around 680.

One important event happened on 17 October 1940. A brave soldier named Second Lieutenant Sandy Campbell had to deal with an unexploded bomb. It had fallen at the Triumph Engineering factory. This bomb had stopped war production at two factories. Campbell found that the bomb had a delayed fuse that he couldn't remove. So, he carefully moved it to a safe place using a lorry. He lay next to the bomb to listen for any ticking. If it started, he would warn the driver to stop and run. He successfully got rid of the bomb. Sadly, he was killed the next day dealing with another bomb. Campbell received a special award, the George Cross, for his bravery.

The Major Attack: 14 November 1940

The raid on the evening of 14 November 1940 was the worst for Coventry. 515 German bombers took part. This attack was called Operation Mondscheinsonate, which means Moonlight Sonata. The Germans wanted to destroy Coventry's factories. But they knew other parts of the city, like homes and famous buildings, would also be hit.

The first group of 13 special Heinkel He 111 planes dropped marker flares at 7:20 PM. These planes had special navigation tools. The British tried to block the German signals, but they didn't succeed that night.

The next waves of bombers dropped high explosive bombs. These bombs knocked out important services like water, electricity, telephones, and gas. They also made huge holes in the roads. This made it very hard for firefighters to reach the fires. Later, bombers dropped both high explosive and incendiary bombs (fire bombs). Some fire bombs were made of magnesium, others of petroleum. The high explosive bombs and larger air-mines were meant to damage roofs. This made it easier for the fire bombs to fall inside buildings and set them on fire.

Coventry had some defenses: 24 large anti-aircraft guns and 12 smaller ones. These guns fired over 6,700 rounds during the 10-hour raid. But only one German bomber was shot down.

Around 8:00 PM, Coventry Cathedral caught fire from incendiary bombs. Volunteer firefighters tried to put out the first fire. But more bombs hit, and new fires started. A firestorm quickly spread the flames out of control. A firestorm is when many fires join together, creating a huge, intense blaze with its own strong winds.

More than 200 other fires started across the city at the same time. Most were in the city center, setting the whole area ablaze. Firefighters were overwhelmed. The telephone system was broken, making it hard for them to communicate and send help where it was needed most. Water pipes were also damaged, so there wasn't enough water to fight many fires. The raid was most intense around midnight. The all-clear signal finally sounded at 6:15 AM on 15 November.

In just one night, over 4,300 homes in Coventry were destroyed. About two-thirds of all buildings in the city were damaged. The city center was hit hardest and mostly destroyed. Two hospitals, two churches, and a police station were also damaged. Many factories were destroyed or badly damaged, including car and aircraft parts factories. However, much of the important war production had already been moved to safer "shadow factories" outside the city. Also, many damaged factories were quickly repaired and were back to full production in a few months.

Around 568 people were killed in the raid, and many more were injured. The exact number of deaths was never fully confirmed. Given how intense the bombing was, the number of casualties was lower than it could have been. This is because many people from Coventry had started "trekking" out of the city at night to sleep in nearby towns after earlier raids. Also, people who used air raid shelters were mostly safe. Very few of the 79 public shelters, which held 33,000 people, were destroyed.

While the city center suffered the most, other areas like Stoke Heath, Foleshill, and Wyken were also heavily bombed.

The destruction in Coventry was so severe that Joseph Goebbels, a German official, later used the term coventriert ("coventried"). He used it to describe similar levels of destruction in other enemy towns. During the raid, the Germans dropped about 500 tons of high explosives. This included 50 large parachute air-mines (some of which were incendiary petroleum mines) and 36,000 fire bombs.

The raid on 14 November used new tactics that influenced later bombing raids:

- Using special "pathfinder" aircraft with electronic tools to mark targets before the main bombers arrived.

- Using a mix of high explosive bombs and thousands of fire bombs to create a firestorm and set the city ablaze.

Later in the war, Allied bombers dropped all their bombs in one quick wave. But at Coventry, German planes carried smaller bomb loads. They attacked in smaller groups, with each bomber returning to France to reload. This meant the attack lasted several hours, with breaks. These breaks allowed firefighters and rescuers to reorganize and help people.

The British used the lessons from the Coventry attack to try a new bombing tactic against Germany. This happened on 16 December 1940 against the city of Mannheim. This marked a shift for the British. They started moving away from precise attacks on military targets towards bombing entire cities.

Did Britain Know About the Attack Beforehand?

After the war, some people claimed that the British government knew about the attack on Coventry beforehand. They said this information came from "Ultra" – secret German radio messages that British code-breakers had decoded. It was even suggested that Winston Churchill, the Prime Minister, ordered no special defenses for Coventry. This was supposedly to keep the Germans from knowing their codes were broken.

However, other people who worked on Ultra and many historians disagree. They say that while Churchill knew a major bombing raid was coming, no one knew for sure that Coventry would be the target.

British code-breakers had identified a code name, Mondschein Sonate ("Moonlight Sonata"), for a planned group of attacks. But they didn't know the exact targets or dates. They had some code names for possible targets, but they didn't connect "KORN" (which was Coventry) to the city at the time.

Peter Calvocoressi, who worked at Bletchley Park (where the codes were broken), said that Ultra never mentioned Coventry. He also said that Churchill thought the raid would be on London.

Also, there was a gap in the decoded messages right before and during the attack. This means Churchill couldn't have received new information about Coventry on the day of the raid.

Later Raids in 1941 and 1942

On the night of 8/9 April 1941, Coventry was hit by another large air raid. 230 bombers dropped 315 tons of high explosives and 25,000 fire bombs. In this raid and another two nights later (10/11 April), about 451 people were killed and over 700 seriously injured.

Many buildings were damaged, including factories, the main police station, and schools. The most significant building destroyed was Christ Church, which lost everything but its spire. After this raid, the Mayor of Coventry, Alfred Robert Grindlay, began the early rebuilding of the city center.

The very last air raid on Coventry happened on 3 August 1942. It hit the Stoke Heath area, about a mile east of the city center. Six people were killed. By this time, a total of 1,236 people had died from air raids on Coventry. Most of them (about 80%) were killed in the major raids of November 1940 and April 1941. Many of those who died are buried in a mass grave at London Road Cemetery.

Rebuilding Coventry

After the war, a committee led by William Rootes, a car industry leader, started the immediate rebuilding. The city center of Coventry was rebuilt following a new plan called the Gibson Plan. This plan was very modern for its time. It created a pedestrian-only shopping area, where people could walk safely without cars.

The old Coventry Cathedral was left as a ruin. Today, it is the most visible reminder of the bombing. A new cathedral was built next to the ruins in the 1950s. The architect, Basil Spence, believed the old cathedral should stay as a garden of remembrance. The new cathedral was built alongside it, making the two buildings feel like one church. The new cathedral used the same type of stone as the old one, which helps connect them.

Queen Elizabeth II laid the foundation stone for the new cathedral on 23 March 1956. It was officially opened on 25 May 1962. For this special occasion, a famous piece of music called War Requiem by Benjamin Britten was performed there for the first time on 30 May.

Spon Street was one of the few areas in the city center that survived the Blitz mostly untouched. During the rebuilding, several old medieval buildings from other parts of the city were moved to Spon Street. The 14th-century St. Mary's Guildhall also survived and can still be seen today. The bombing, while destructive, also uncovered an old medieval stone building on Much Park Street, which is thought to be from the 13th or 14th century.

See also

- 1939 Coventry bombing

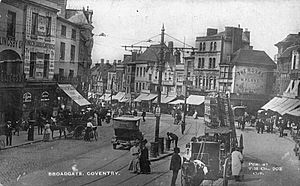

- History of Coventry

- Birmingham Blitz

| Georgia Louise Harris Brown |

| Julian Abele |

| Norma Merrick Sklarek |

| William Sidney Pittman |