History of Coventry facts for kids

This article explores the history of Coventry, a city located in the West Midlands of England. Coventry became a very important city in England during the Middle Ages because of its successful cloth and textile trade. The city played a key role in the English Civil War and later became a major industrial hub in the 1800s and 1900s. It was known as the center for British bicycle and later motor car manufacturing.

Sadly, a terrible bombing raid called the Blitz in 1940 destroyed much of the city center. Coventry was rebuilt in the 1950s and 60s. The car industry faced difficulties in the 1970s and 80s, leading to high unemployment. However, in the 2000s, Coventry saw a big comeback. In 2017, it was even named the 2021 UK City of Culture.

Contents

Coventry's Early Beginnings

First Settlements and Name

Not much is known about Coventry's very first days. Before Coventry existed, there were settlements nearby in Corley and Baginton. These places were settled by the Romans and later by Saxon invaders. They were likely chosen because they were on old paths and had light, easy-to-farm soil, unlike the heavy, marshy land where Coventry would later grow.

It's thought that the first settlement in Coventry grew around a Saxon nunnery. This nunnery was started around AD 700 by St. Osburga. The Saxon settlers cleared the land, which was mostly forest, and focused on raising cattle and sheep. This eventually led to Coventry's famous wool industry and its great wealth.

The name "Coventry" likely comes from this time. One popular idea is that it means "Cofa's tree" (or "Coffa's tree"). We don't know who Cofa was, but a tree planted by or named after him might have marked the center of the settlement. Another idea is "Coventre," which combines "Coven" (an old word for "Convent") and "tre" (a Celtic word for "settlement" or "town"), meaning "Convent Town."

Founding of St. Mary's Priory and Cathedral

The first recorded event in Coventry's history happened in 1016. King Canute and his Danish army were destroying towns in Warwickshire. When they reached Coventry, they destroyed the Saxon nunnery.

Later, in 1043, Leofric, Earl of Mercia, and his wife Lady Godiva rebuilt the nunnery. They founded a Benedictine monastery dedicated to St. Mary for an abbot and 24 monks. Leofric was one of the most powerful men in England, and Godiva was also very important, owning a lot of land.

A writer named John of Worcester said that Leofric and Godiva built the monastery from their own money. They gave it so much land and beautiful decorations that no other monastery in England had as much gold, silver, and precious stones. King Edward the Confessor supported their good deed and confirmed their gift.

The famous story of Lady Godiva says she felt sorry for the people of Coventry because her husband, Leofric, taxed them too much. She asked him many times to lower the taxes, but he always refused. Finally, he said he would agree if she rode naked through the town streets. Godiva did this, asking everyone to stay indoors and close their windows. After her ride, Leofric supposedly kept his promise and removed the harsh taxes. However, historical facts don't fully support this legend.

Around 1095, Bishop Robert de Limesey moved his main church (his see) to Coventry. In 1102, the Pope approved this move, turning St. Mary's monastery into a priory and cathedral. The rebuilding and expansion of St. Mary's took about 125 years to complete.

In 2000 and 2001, archaeologists from the TV show Time Team found important remains of this large old cathedral and monastery complex (St. Mary's) next to the current cathedral.

When the monastery was founded, Leofric gave the northern half of his Coventry lands to the monks. This became known as the "Prior's-half." The other half was called the "Earl's-half" and later belonged to the Earls of Chester. This explains why Coventry was divided into two parts until 1345. In 1250, the Earl at the time, Roger de Mold, sold his rights to the southern side of Coventry to the Prior. For the next 95 years, one "land lord" controlled the town. However, there were arguments between the monks' tenants and the Earl's former tenants, and the Prior never fully controlled Coventry.

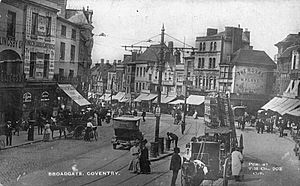

Coventry's Castle History

Coventry Castle was first built in the late 1000s by Ranulph le Meschin, 1st Earl of Chester. It was torn down in the 1100s but rebuilt around 1137-1140 by Ranulph de Gernon, 2nd Earl of Chester. He successfully defended it against King Stephen during a civil war known as The Anarchy. We don't know the exact spot of the castle, but Broadgate, Coventry's city center, refers to the "broad gate" or main entrance to the castle, so it must have been nearby.

Over time, merchants and traders settled around the monastery and castle. A market was set up at the monastery gates, and new houses appeared. Two churches were built: Holy Trinity for the Prior's tenants and St. Michael's for those in the Earl's half. From then on, Coventry started to become more organized, with streets and trading areas, much like London.

Ranulf's son, Hugh de Kevelioc, 3rd Earl of Chester, took over as earl. In 1173, he held Coventry's castle against King Henry II. Henry sent a strong army to Coventry, which likely damaged the castle badly. What was left of the castle eventually fell apart and disappeared. From the 1200s, the manor house at Cheylesmore became the earls' home instead.

One of the last times the castle was mentioned was in 1569. After the Catholic Rising of the North, Mary, Queen of Scots was quickly moved from Tutbury Castle to Coventry. Queen Elizabeth I suggested Mary be held in a secure place like Coventry Castle. However, by then it was too ruined. Mary was first held at the Bull Inn and then at the Mayoress's Parlour in St. Mary's Guildhall.

Growth and Wealth

Coventry might not have become important without Leofric and Godiva founding the monastery. But other things helped it grow too. The River Sherbourne ran through the town, providing water and power for mills. There was also plenty of timber nearby for fuel and building. Stone was dug up from nearby Whitley and Cheylesmore. Good farmland and open common areas surrounded Coventry. Its central location, close to old Roman roads like Watling Street and the Fosse Way, made it perfect for trade.

Early Trade and Products

The people of Coventry themselves helped the town grow. Between 1150 and 1200, they received three special permissions (charters) from the Earls of Chester and King Henry II. One of these allowed any merchants coming to town to trade peacefully. If they wanted to settle, they wouldn't have to pay rent or fees for two years. This quickly encouraged the trade of local goods like wool, soap, needles, metal, and leather items.

The large grazing lands around the town were great for sheep farming and wool production. By the 1200s, Coventry became a center for many textile trades, especially those related to wool. Coventry's wealth came mostly from its dyers who made "Coventry blue" cloth. This cloth was very popular across Europe because its color didn't fade. This is believed to be where the saying true blue comes from, meaning something that stays fast or true.

This trade was boosted by a 1273 charter that allowed exports "beyond the seas." Then, in 1334, traders were freed from tolls and other fees for their goods throughout the kingdom. In 1340, they were allowed to form a merchant guild to protect these rights.

Besides wool, Coventry also had a small but busy trade in glass-making, glass painting, and tile making. By the 1300s and throughout the medieval period, Coventry was the fourth largest city in England, with about 10,000 people. Only Norwich, Bristol, and London were bigger.

City Walls

To show Coventry's importance for trade and defense, construction began on city walls in 1355. This was a huge and expensive project, paid for by local tolls and taxes. King Richard II even allowed stone to be taken from his park in Cheylesmore. Building started at New Gate and was mostly finished around 1400. However, a lot of repair and re-routing work was done later, and the walls were not fully completed until 1534.

They were very impressive: nearly 2.2 miles (3.5 km) long, made of two red sandstone walls filled with rubble, over 8 feet (2.4 m) thick and 12 feet (3.7 m) high. They had 32 towers, including 12 gatehouses. With its walls, Coventry was considered the best-defended city in England, apart from London.

Major Buildings

By the 1400s, the city's size was mostly set, and its streets and main buildings were largely finished. Inside the city walls were many impressive churches. Holy Trinity had been greatly enlarged. St. Michael's had been rebuilt as one of England's largest parish churches, with a magnificent tower and spire. The nearby priory and its cathedral church now dominated the area and might have had three spires itself. The church of the greyfriars (later Christ Church) also had a spire. The guild church of St. John the Baptist at Bablake had a short square tower.

The whitefriars or Carmelites had a church near the remains of their friary, and there was also a church belonging to the hospital of St. John. The Guest House provided lodging for pilgrims visiting the priory, and many inns in the city served travelers, merchants, and locals.

In 1465, the Coventry mint was set up, where nobles, half-nobles, and groats were made. It closed a few years later, and the Golden Cross inn, built in 1583, now stands on that site. St. Mary's Hall, built and expanded between 1340 and 1460, served as the main office for several united guilds. After guilds were banned in 1547, it became the city's armory and treasury, and the city council's headquarters until a new Council House opened in 1920.

Coventry's famous "Three Spires" belonged to St. Michael's (300 ft / 91 m), Holy Trinity (about 230 ft / 70 m), and Christ Church (Greyfriars, just over 200 ft / 61 m). They stood tall in the skyline, making an impressive and easily recognizable landmark for visitors, visible from far away.

When the famous historian John Leland visited Coventry around 1540, he was impressed by the "many fayre towers in the waulle" and "stately churches in the harte and midle of the towne," as well as its "many fayre stretes...well buyldyd with tymbar."

Royalty and Parliament in Coventry

Coventry's growing importance was shown by the many royal visits it received. In recognition of its status, King Edward III granted Coventry a city charter in 1345. This gave the city the right to govern itself, including electing a mayor.

In 1398, King Richard II gathered all the nobles of the kingdom at Gosford Green to watch a fight between Henry Bolingbroke (who later became King Henry IV) and Thomas de Mowbray, 1st Duke of Norfolk. They were exiled instead to prevent bloodshed.

Coventry was briefly the capital of England several times. In 1404, Henry IV called a parliament in Coventry because he needed money to fight a rebellion, and wealthy cities like Coventry lent it to him. Both Henry V and Henry VI often borrowed money from the city for the war with France. During the Wars of the Roses, the Royal Court moved to Coventry with Margaret of Anjou, Henry VI's wife. Parliament met in Coventry several times between 1456 and 1459, making it the effective seat of government for a while. This ended in 1461 when Edward IV became king.

In 1451, King Henry VI granted Coventry a charter making it its own county. It kept this status until 1842, when it became part of Warwickshire again. During this time, it was known as the County of the City of Coventry. The original city hall was replaced in 1784 by the current building, still called "County Hall" as a reminder of this period.

Cheylesmore Manor House, now home to Coventry's Register office, hosted royals like Edward, the Black Prince and Henry VI. Parts of the building date back to 1250. Edward's grandmother, Queen Isabella of France, gained the rights to the manor. It's said that Edward often visited the area and used Cheylesmore Manor as his hunting lodge.

Edward's armor was black, which is why he was called the "Black Prince." His helmet had a "cat-a-mountain" on top. The city's seal has the motto "Camera Principis" or the Prince's Chamber, which is said to come from its close connection to the Black Prince. The cat-a-mountain also sits on top of Coventry's Coat of Arms.

In the 1500s, the cloth trade declined due to strict rules by trade guilds, and Coventry faced hard times. To make things worse, King Henry VIII dissolved monasteries during the English Reformation. This meant Coventry's monastery and other religious houses were destroyed, followed by the banning of religious guilds.

However, most Coventry citizens seemed to prefer the new Protestant religion and the English Bible. When Queen Mary I tried to bring back the Roman Catholic religion, many people in Coventry suffered punishment rather than give up their beliefs. Between 1510 and 1555, 12 Protestant martyrs were burned to death. A memorial to 11 of these Coventry Martyrs now stands near the execution site in Little Park. Three famous martyrs, Cornelius Bongey, Robert Glover, and Laurence Saunders, were burned in 1555.

Queen Elizabeth I stayed at the Whitefriars in 1565. In 1569, Mary, Queen of Scots, was held at St. Mary's Hall at Elizabeth's request.

Civil War and Its Aftermath

King James I visited Coventry in 1617 and was welcomed with a grand feast. But relations between the monarchy and Coventry worsened later. People protested against his son, King Charles I, asking for a lot of "ship-money" in 1635. Because of this, when the English Civil War broke out between King Charles I and Parliament, Coventry became a strong base for Parliament's forces. Royalist forces attacked Coventry several times but could never break through the city walls.

The King tried to take the town in late August 1642 with 6,000 horse troops. But the Coventry soldiers and townspeople strongly pushed them back. In 1645, the parliamentary army in Coventry had 156 officers and 1,120 soldiers. They were supported by troops from nearby villages.

Coventry was used to hold Royalist prisoners. It's believed that the phrase "send to Coventry" (meaning to be ignored or treated coldly) might have come from how the city's residents treated either the soldiers staying there or the Scottish Royalist prisoners held in the Church of St. John the Baptist after the Battle of Preston. Another idea is that Coventry was a place where supposed heretics were sent to be burned in the 1500s.

In 1662, after the monarchy was restored, King Charles II ordered the city walls to be torn down. This was revenge for Coventry supporting Parliament during the Civil War. Today, only a few short sections and two city gatehouses remain. When his brother, King James II, visited the city in 1687, he received a grand welcome, showing loyalty to the Crown. However, within two years, most of the same people were celebrating the arrival of William of Orange.

Industrial Growth

During Coventry's industrial growth, it connected to the growing national transport systems. The Coventry Canal opened in the late 1700s. One of the first major railway lines, the London and Birmingham Railway, was built through Coventry and opened in 1838.

Textile Industry

A silk weaving company started in Coventry in 1627. Around the early 1700s, a ribbon weaving factory was set up by a Mr. Bird, likely William Bird, who was mayor in 1705. He was helped by Huguenot refugees who brought their silk and ribbon weaving skills. This trade grew quickly, and by the late 1700s, it was the main part of the city's economy. Coventry began to recover and became a major center for clothing trades again.

At first, single-shuttle hand-looms were used, later joined by engine looms. By 1818, Coventry had 5,483 single hand-looms and 3,008 engine looms, with nearly 10,000 workers. This number peaked at about 25,000 workers in 1857. A major employer was J&J Cash Ltd (Cash's), a silk weaving company started in the 1840s in Foleshill.

This first industrial boom ended suddenly in the 1860s when foreign imports ruined the industry, and Coventry went into a slump. However, other industries soon began to grow, and Coventry became prosperous again. These new industries included watch and clock making, sewing machine manufacturing, and from the 1880s onwards, bicycle production.

Clocks and Watches

In the 1700s and 1800s, Coventry became one of the three main centers in the UK for making watches and clocks. Its origins in this trade can be traced back to the late 1600s. Samuel Watson, who was sheriff of Coventry in 1682, became famous for making a clever astronomical clock. John Carte, a watchmaker from Coventry, had his own business in London by 1695. The mayor of Coventry in 1727 was a watchmaker named George Porter.

The company "Vale" was started in the late 1740s, and "Rotherhams" began business in 1750. The next 60 years saw fast growth in the trade, with factories and workshops appearing. From 1825 to 1850, Coventry's watch business almost doubled. In 1861, about 2,037 people worked in the trade. As the industry declined from 1880 due to competition from American and Swiss manufacturers, the skilled workers were crucial. They helped set up sewing machine and bicycle manufacturing, and later the motorcycle, automobile, machine tool, and aircraft industries. However, Rotherhams was still making 100 watches a day in 1899, even when many other watchmakers had closed.

Cycles and Bicycles

The start of bicycle production in Coventry came from making sewing machines at the Coventry Machinists Company. This company was founded in 1861 by James Starley. The company made several successful sewing machine models. In 1868, Starley and his company were convinced to make the French-designed bone-shaker bicycles.

Starley improved the design, leading to the "Penny farthing" and more practical tricycle designs. But it was his nephew, John Kemp Starley, who invented the first modern bicycle, the "Starley Safety Bicycle." Made by Rover in 1885, it was the first bicycle with modern features like a chain-driven rear wheel and equal-sized wheels.

By the 1890s, the bicycle trade was booming, and Coventry had the largest bicycle industry in the world. The industry employed nearly 40,000 workers in 248 bicycle factories in Coventry. The peak year was 1896. In 1906, for example, the Rudge-Whitworth Company alone made 75,000 of the over 300,000 bicycles produced in the city that year.

Changes to the City

This period of industrial growth changed the city's size and look. The city walls had been mostly pulled down in 1662. But at the start of the 1700s, Coventry's layout still looked much like it did in medieval times, with very old, sometimes decaying, buildings.

Daniel Defoe wrote: "The city may be taken for the very picture of the city of London, on the south side of the Cheapside before the Great Fire; the timber-built houses, projecting forwards and towards one another, til in the narrow streets they were ready to touch one another at the top."

With the arrival of toll roads, regular stagecoach services, and more road traffic, the old city gates, designed for horses and carts, now blocked traffic flow. Five of them were removed in the 1700s, and all but two of the rest were torn down in the next century.

As industry grew, the population increased rapidly, and more housing was needed. Since all existing streets were already built up, new houses were built on open spaces, gardens, and land behind existing properties. Others were built outside the old city area. In 30 years, the number of houses in Coventry almost doubled, from 2,930 in 1801 to 5,865 in 1831.

In 1842, an Act of Parliament took away Coventry's county status and redefined its boundaries as a city. But to allow for expansion, the new boundaries included 1,486 acres (6.01 km2), much larger than the old walled city. Over the next 50 years, two more boundary extensions brought in more outlying areas, increasing the city to 4,417 acres (16.78 km2) by 1899.

Coventry in the 20th Century

Industrial Growth Continues

Coventry continued to produce ribbons, woven labels, and other small textile items. In 1904, Courtaulds opened its first silk factory in Foleshill, Coventry. This company was the first in Britain to produce nylon yarn in 1941.

The first British motor car was made in Coventry in 1897 by The Daimler Motor Company Limited. More small car manufacturers started to appear. This new industry grew slowly at first, but within 10 years, the motor trade employed about 10,000 people. By the 1930s, car manufacturing had largely replaced bicycle making, employing 38,000 people by 1939. Coventry became a center of the British motor industry. Famous British car makers like Jaguar, Rover, and Rootes were based there.

The cycle and motor manufacturing industries led to many related businesses. These included general engineering, metal casting, chain-making, and making instruments, machine tools, and electrical equipment. Aircraft, aero engines, and related equipment were also made in Coventry as early as 1916. During World War II, the aircraft industry became the largest local industry. When the war started, many car companies switched to making aircraft parts, and all of Coventry's industrial skills turned to war production.

Changing City Life

Construction of a new Council House, to take over administrative duties from St. Mary's Hall, began in 1913. It was designed to fit with its medieval surroundings but was delayed during World War I. It was finished by 1917 but officially opened on June 11, 1920, by H.R.H. the Duke of York, who later became King George VI.

As late as the 1920s, Coventry was called "The best preserved Medieval City in England." Before the devastating Blitz, novelist J. B. Priestley visited and wrote: "I knew it was an old place, but I was surprised to find how much of the past, in soaring stone and carved wood, still remained in the city." However, the narrow medieval streets were not good for modern car traffic. In the 1930s, many old streets were cleared to make wider roads, creating a strange mix of old and new buildings.

The city remained wealthy and was mostly unaffected by the economic slump of that decade. In fact, Coventry's population grew by 90,000 in the 1930s. Another boundary extension in 1928 brought more districts into the city limits. Many new housing estates were quickly built, especially in these new areas, but barely fast enough to meet demand. By 1947, Coventry's boundaries covered 19,167 acres (77.57 km2).

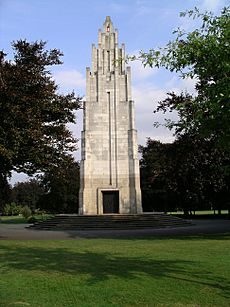

To meet the needs of the growing population, the Coventry Corporation Act of 1927 changed Whitley Common, Hearsall Common, Barras Heath, and Radford Common into recreation grounds. It also ended all traditional commoning rights on waste ground in Coventry. The freemen of the city, who had been allowed to graze up to three animals in these areas since 1833, each received £100 annually as compensation. The Council had already bought Styvechale Common after World War I to create the War Memorial Park. In 1927, a monument was built in the park to remember all Coventrians who died in that war and later conflicts.

IRA Attack

Nine days before World War II began, on August 25, 1939, Coventry experienced an early bomb attack on the mainland by the IRA. At 2:30 in the afternoon, a bomb exploded inside a tradesman's bicycle basket left outside a shop in Broadgate. The explosion killed five people, injured 100 more, and caused a lot of damage to shops. Two IRA members and three others were put on trial for murder. Three were found not guilty, and two were convicted and hanged in February 1940. The person who rode the bicycle to Broadgate and planted the bomb was never found.

Bombing During the Blitz

Coventry's hardest time came during World War II when Adolf Hitler specifically targeted the city for heavy bombing. Large parts of the city were destroyed in a massive German bombing raid on the night of November 14/15, 1940. Firefighters from all over the Midlands came to help, but they found that each fire brigade had different hose connections. This meant much firefighting equipment couldn't be used.

The attack destroyed most of the city center and the city's medieval cathedral. 568 people were killed, 4,330 homes were destroyed, and thousands more were damaged. Industry was also badly hit, with 75% of factories damaged. However, war production was only briefly stopped, as much of it continued in hidden factories around the city and further away. Besides London and Plymouth, Coventry suffered more damage than any other British city during the German air attacks, with huge firestorms destroying most of the city center.

The city was targeted because it had many armaments, munitions, and engine plants that greatly helped the British war effort. Residential areas were not specifically targeted, though factories like the Armstrong Siddeley aero engine plant were in or near some of them. After the raids, most of Coventry's historic buildings could not be saved because they were ruined or considered unsafe.

The destruction was so great that the German word Koventrieren – meaning to "Coventrate," or to completely destroy and reduce to rubble – entered both the German and English languages. In response, the Royal Air Force increased its carpet bombings against German towns.

On April 8, 1941, Coventry was hit by another massive air raid, bringing the total killed in the city by bombing to 1,236, with 1,746 injured.

A common myth about the bombing is that Coventry was deliberately left undefended. This was supposedly to prevent the Germans from realizing that information from the Enigma cipher machine (called Ultra) was being read by British code-breakers at Bletchley Park. This claim is not true. Winston Churchill knew a major bombing raid was coming, but no one knew beforehand exactly where the raid would strike.

After the War

After the war, the city was extensively rebuilt. The new city center, built in the 1950s, was designed by young town planner Donald Gibson. It included one of Europe's first traffic-free shopping areas, an idea copied worldwide after Rotterdam's first one in 1946.

The new Broadgate was opened by H.R.H. Princess Elizabeth in 1948. The rebuilt Coventry Cathedral opened in 1962, next to and including the ruins of the old cathedral. It was designed by Basil Spence and features the tapestry "Christ in Majesty" by Graham Sutherland and the bronze statue "St. Michael and the Devil" by Jacob Epstein on its outer wall.

Because of the postwar rebuilding, Coventry now has a lot of 1960s-style architecture, with concrete and brutalist designs. The development of Coventry's central business district was limited by a major orbital ring road built in the early 1970s. This led to a mix of city zones with no clear functions, except for the cathedral area and an older 1950s shopping area. The Cathedral Lanes shopping complex built in 1990 at Broadgate changed the original layout significantly.

However, several parts of the city center still have beautiful medieval and neo-Gothic buildings. These include Ford's Hospital, The Golden Cross, St Mary's Guildhall, Spon Street, the Old Blue Coat School, the Council House, and Holy Trinity Church. These survived both the Blitz and the postwar planners.

The city was twinned with Dresden, a German city that suffered an even more devastating bombing attack late in the war. Groups from both cities worked together on projects of post-war reconciliation. Today, Coventry has a strong partnership with Dresden, supported by people in both cities. Coventry played a major role when the reconstruction of the Dresden Frauenkirche was completed in 2003.

Throughout the 1950s and until the mid-1970s, Coventry remained wealthy. It was often called "Motor City" or "Britain's Detroit" because of the many car production plants. These included Jaguar, Standard-Triumph, Hillman-Chrysler (later Talbot and Peugeot), and Alvis. During this time, the city had one of the highest living standards in the country, outside of southeast England. The city's population peaked in the late 1960s at around 335,000.

New, high-quality housing developments, especially in the city's southern suburbs (like Cannon Park and Styvechale Grange), served a larger middle-class population. Along with some of the UK's best sports and leisure facilities, including an Olympic-standard swimming complex and a pedestrianized shopping area, Coventrians enjoyed a short "golden age."

However, the decline of the British motor industry in the late 1970s and 80s hit Coventry hard. In the early 1980s, up to 20% of the workforce was unemployed, one of the highest rates in the UK. A quick rise in petty crime also started to give the city a poor reputation. A hit song, "Ghost Town" by local band The Specials, was widely believed to be about Coventry and summed up the city's situation in the summer of 1981.

The economic recession of 1990 to 1992 also affected the city severely. But in recent years, Coventry has largely recovered, undergoing significant redevelopment and attracting newer industries. However, car production still exists today at the LTI (London Taxis International, formerly Carbodies) plant in Holyhead Road. This plant employs 450 people and makes the popular "black cab," the current model being the TX4. The world-famous FX4 black cabs were made in Coventry from 1959 to 1994.

Coventry's famous medieval "Three Spires" – belonging to St. Michael's, Holy Trinity, and Christ Church (greyfriars) – have continued to stand tall in the skyline. Although all three spires survived, today only the church of Holy Trinity remains intact and in use. The church of the greyfriars was torn down during the English Reformation, and only the walls and spire of St. Michael's survived the Coventry Blitz.

Coventry's Population Over Time

- 16,000 (1801)

- 62,000 (1901)

- 220,000 (1945)

- 258,211 (1951)

- 335,238 (1971)

- 300,800 (2001)

Important People and Supporters

Leofric, Earl of Mercia, and his wife Lady Godiva were responsible for the first major act of kindness when they founded a monastery in early Coventry. Here are some other notable people who have helped the city grow:

- Thomas Bond: A draper who founded Bond's Hospital in 1506. He was also mayor of Coventry in 1497.

- The Botoners: A merchant family believed to have played a key role in building St. Michael's church-tower, spire, chancel, and nave.

- Andrew Carnegie: An outside supporter who gave £10,000 to the city for building libraries in Stoke, Earlsdon, and Foleshill, all opened in 1913.

- William Ford: A merchant who founded Ford's hospital in 1529.

- John Gulson: Founded Coventry's public library service and was mayor twice (1867–69). He donated the land and most of the money for the Gulson library next to Holy Trinity church, which opened in 1873. He also added a reference library in 1890.

- John Hales: A writer and politician who founded Coventry's Free Grammar school in 1545.

- Sir Alfred Herbert: A pioneer in machine-tool production. He turned a slum area into the public garden "Lady Herbert's Garden" in 1930. He also built and funded "Lady Herbert's Homes" – two blocks of dwellings next to the garden. He paid for the restoration of the longest remaining part of the city walls and Swanswell gate. He gave an initial gift of £100,000 and later donations for an art gallery and museum.

- Lord Iliffe: Presented Allesley Hall and its grounds to the city in 1937. He also donated £35,000 towards rebuilding Coventry Cathedral.

- William Pisford: Co-founder of Ford's hospital.

- Thomas Wheatley: Founder of Bablake school in 1560 and mayor of Coventry in 1556.

- Sir Thomas White: A merchant and businessman known for many acts of kindness. This included a gift of £1,400 in 1542 for the city to buy lands to be held in trust for charitable purposes. The money from these lands was shared among deserving freemen of the city. (He was also mayor of London in 1553 and founder of St. John's College, Oxford.)

- Sir William Wyley: A supporter and mayor twice (1911–13). He bought and gave Cook Street gate to the city in 1913. He also left his home, the Charterhouse, to the city in 1940.

Images for kids