David Einhorn (rabbi) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

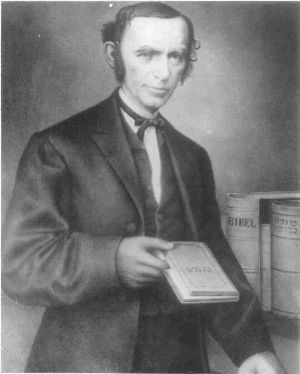

David Einhorn

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | November 10, 1809 (2 Kislev 5570) Diespeck, Kingdom of Bavaria

|

| Died | November 2, 1879 (aged 69) (16 Cheshvan 5640) New York, New York, United States

|

| Education | University of Erlangen-Nuremberg, University of Munich, University of Würzburg |

| Occupation | Reform rabbi |

| Parent(s) | Maier and Karoline Einhorn |

David Einhorn (November 10, 1809 – November 2, 1879) was an important German rabbi who became a leader of Reform Judaism in the United States. He was known for his strong beliefs and for creating new prayer books. He also bravely spoke out against slavery during a difficult time in American history.

In 1855, Einhorn became the first rabbi of the Har Sinai Congregation in Baltimore. This was the oldest Jewish community in the U.S. to be part of the Reform movement from the start. While there, he wrote an early American prayer book. This book later helped create the 1894 Union Prayer Book.

Contents

Early Life and Learning

David Einhorn was born in a place called Diespeck in Germany on November 10, 1809. His parents were Maier and Karoline Einhorn.

He went to a special school for rabbis in Fürth. He became a rabbi at just 17 years old. After that, he studied at the universities of Erlangen, Munich, and Würzburg from 1828 to 1834. His mother supported him after his father passed away.

His Beliefs and Challenges

Einhorn believed in making changes to Jewish practices. He supported the ideas of another important rabbi, Abraham Geiger. While still in Germany, Einhorn wanted prayers to be said in German, not just Hebrew.

He also believed that some old traditions, like hoping for the rebuilding of the Temple in Jerusalem, should be removed from synagogue services. He worked to make these changes happen at a meeting in Frankfurt in 1844.

Einhorn became a chief rabbi in different parts of Germany. He followed Rabbi Samuel Holdheim, whose ideas greatly influenced him.

In 1851, he was called to Pest, Hungary. But his ideas faced strong opposition there. The ruler of Austria ordered his temple closed only two months after he arrived. The ruler thought that the Jewish reform movement was connected to the revolutions happening in Europe at the time.

Leading Reform Judaism in America

Einhorn moved to the United States. On September 29, 1855, he became the first rabbi of the Har Sinai Congregation in Baltimore. In this role, Einhorn created a prayer book called Olat Tamid.

This prayer book became a model for the Union Prayer Book, which was published in 1894. Olat Tamid was different from other prayer books. For example, it removed mentions of Jews as a "chosen people." It also took out references to bringing back old sacrificial services in the Temple.

Einhorn did not agree with the Cleveland Conference of 1855. This meeting decided that the Talmud (a collection of Jewish laws and traditions) was most important for understanding the Torah (Jewish holy texts). Einhorn felt that focusing too much on the Talmud went against the progress of reform.

In 1856, he started a German-language magazine called Sinai. This magazine was about making big changes in Jewish practices. He also used it to speak out against slavery.

Einhorn believed that marriage between different faiths was harmful. He wrote in Sinai that it was "a nail in the coffin of the small Jewish race." However, he also thought that some old practices, like wearing phylacteries (small boxes with scriptures), strict rules for Shabbat, and kosher dietary laws, were outdated. He believed only the moral parts of the Torah should be kept. By 1858, he was seen as the main leader of Reform Judaism in America. He published a revised prayer book that became a model for future versions.

Speaking Out Against Slavery

In 1861, Rabbi Morris Jacob Raphall gave a sermon that supported slavery. Einhorn strongly disagreed. He gave his own sermon, calling slavery a "deplorable farce." He argued that slavery in the South did not fit with Jewish values.

He reminded people that Jewish people were once slaves in Egypt. This experience, he said, should make Jews more understanding of others who are enslaved. He held this view firmly, even though many people in his community in Maryland, which was a slave state, supported slavery.

In his sermon called War on Amalek, Einhorn said that slavery was a crime. He argued that people who supported slavery often tried to use old religious texts to justify it. He believed that the true spirit of the Bible was against slavery.

On April 19, 1861, a riot broke out because of his sermon. A group of people tried to harm him. Einhorn had to flee to Philadelphia. There, he became the spiritual leader of Congregation Keneseth Israel.

Later Years and Legacy

In 1866, Einhorn moved to New York City. He became the first rabbi of Congregation Adas Jeshurun. This congregation later merged with another, forming Congregation Beth-El in 1873.

Einhorn continued to be the spiritual leader of the new, merged synagogue. He gave his last sermon on July 12, 1879. The congregation agreed to give him a pension after his retirement.

When he retired, other rabbis from different Jewish groups honored him. They held a farewell ceremony at his home because he was not well. They recognized his great service as a rabbi, praising his "ability and character" and his "earnestness, honesty and zeal." They called him "one of Israel's purest champions and noblest teachers."

Einhorn passed away four months later, on November 2, 1879. He was 69 years old and had become very weak. His funeral was held at Beth-El, with many people attending. Important rabbis, including his son-in-law and successor Kaufmann Kohler, were there. He was buried at Machpelah Cemetery.