Denver Tramway facts for kids

The Denver Tramway was a public transportation system in Denver, Colorado. It started in 1886 and mainly used streetcars. A streetcar is like a train that runs on tracks in city streets.

The Denver Tramway was a bit unusual. The word "tramway" isn't commonly used in the United States. Also, its tracks were a "narrow gauge" of 3 feet 6 inches. This was different from most train tracks in the U.S., but common in places like Japan and Australia.

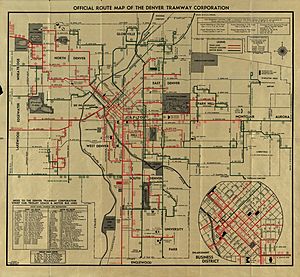

Over the years, the tramway used different types of streetcars. These included early "conduit cars," then "cable cars," and finally "trolley cars." At its busiest, the tramway had over 160 miles (250 km) of track. It also operated more than 250 streetcars.

Streetcar service stopped in 1950. After that, the company used trolley coaches (buses that get power from overhead electric lines) and regular buses. The Denver Tramway Corporation stopped running Denver's transit system in 1971. The city took over operations, and later, the Regional Transportation District (RTD) began managing public transport in Denver.

Contents

History of Denver's Public Transport

Early Days with Horse-Powered Cars

Public transportation in Denver began even before the Denver Tramway. In 1867, a company called the Denver Horse Railroad Company was formed. They had the special right to build a horse railroad in Denver for 35 years.

In 1871, the first horse-drawn streetcar line opened in West Denver. It ran from Seventh and Larimer to the Five Points neighborhood. This company later changed its name to the Denver City Railway Company in 1872. By 1877, it had 32 horses, 12 cars, and carried nearly 400,000 passengers a year.

By 1883, the Denver City Railway Company got new owners. They expanded the railway and improved the tracks. People said Denver's streetcar service was as good as any city its size.

New Companies and the Start of the Tramway

Some land speculators wanted streetcar service for their properties. So, they started a new company in 1885 called the Denver Electric and Cable Railway Company. This company planned to use electricity or cable power.

However, they worried these new methods might not make money. So, they got permission to use horse-power, even though the Denver City Railway Company had the exclusive right to horse railroads. This caused problems between the companies. Eventually, a new company was formed and renamed the Denver Tramway.

Trying Out New Technologies

The Denver Tramway tried an underground electric system in 1886. But it was too expensive and had many problems. After a year, it wasn't making money, so the Denver Tramway went back to using horse-power.

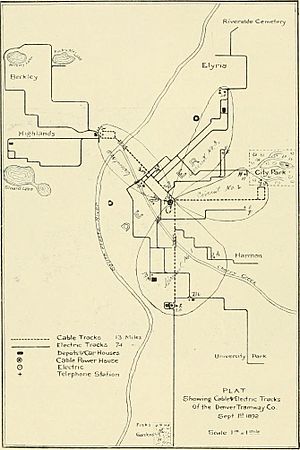

Later, they switched to cable-power and opened their first cable car line in 1888. The Denver City Railway Company, now called the Denver City Cable Railway Company, also switched to cable-power. Both companies were strong competitors, trying to be the best.

In 1888, a new and better electric street railway was invented. The Denver Tramway noticed how successful it was. They decided to build an electric streetcar line into South Denver. This line worked so well that the Denver Tramway decided to switch all its cable lines to electric power. Electric streetcars were cheaper to run than cable cars.

The Denver Tramway then started to grow even more. They bought smaller companies in nearby areas like Berkeley and Highland. By the end of this period, the company owned over a hundred miles of electric track. They also became very connected with local politicians.

Growth and Becoming a Monopoly

The Denver Tramway often faced challenges and went to court. But they had good relationships with the city leaders. These leaders often changed rules to help the company. In 1893, the Colorado Supreme Court first said that the Tramway's "perpetual franchise" (meaning they could operate forever) was against the law. But the company used its political power to have the case re-examined. The Supreme Court then changed its mind and said the perpetual franchise was legal.

By 1893, the Denver Tramway had made its whole system electric and kept expanding. The owners combined their two main companies into The Denver Consolidated Tramway Company. Their biggest rival was still the Denver City Cable Railway Company.

Then, a big economic downturn called the panic of 1893 hit. This gave the Tramway company a chance to get rid of its competition. In November 1893, the Denver City Cable Railway Company ran into financial trouble. The Tramway company used its connections with the city to get a special agreement that the rival company couldn't match. The two companies then merged to become the Denver City Tramway Company.

Now, the company had a monopoly on Denver's street railway service. This meant they were the only ones providing it. They claimed they had the right to operate forever. Advertisements for their stock even said they owned the entire city railway system, with 156 miles of track, and a "perpetual" right to operate.

Public Opinion Changes

With its monopoly and political power, the company focused on making more money. Many people in Denver felt the company wasn't paying the city enough. In 1895, Thomas S. McMurry became mayor. He wanted the city government to be separate from big companies like the Tramway. He wanted the company to give a share of its profits to the city each year.

The company fought against McMurry, and he lost the 1899 election. With a new mayor who was more friendly to the company, the Tramway didn't have to share its profits with the city.

However, public opinion started to turn against the Denver City Tramway Company. People were especially upset in 1905, when the company's original right to operate should have ended. The company still claimed its "perpetual franchise." But as a backup, they created a new agreement in 1906 to try and calm the public.

In 1910, the Colorado Supreme Court ruled again. This time, they said that all "perpetual franchises" were against the state constitution. So, the only valid agreement for the Tramway was the one made in 1906.

The 1906 agreement was very good for the company. It set the fare at 5 cents and said the company would pay half the costs to maintain roads where its tracks ran. As more automobiles appeared, roads wore out faster. Even though the company had record numbers of riders (62 million trips a year by 1917), it couldn't raise fares to cover its higher costs.

The company asked for a fare increase, and the state's Public Utilities Commission allowed a 2-cent increase. But the city of Denver sued. In 1919, Dewey C. Bailey was elected mayor, promising to bring back the 5-cent fare. The Denver Tramway Company responded by cutting jobs and wages.

The 1920 Strike

In 1920, the Tramway company again threatened to cut employee wages. This would happen unless the city let them increase fares. Workers wanted a raise after their wages had been cut for 18 months. The public didn't want higher fares, and the city wouldn't allow it.

Tramway workers voted to go on strike. The company brought in new workers to replace them. This led to violence, and federal troops had to step in. In the end, the Denver Tramway Company went bankrupt.

The bankruptcy court allowed a fare increase, which helped the company recover. But years of not having enough money, plus more people owning cars, meant fewer Denver residents used the streetcar system.

The End of Streetcars

In 1924, the Denver Tramway started its first bus service. It began to replace streetcars with trolley coaches (electric buses) and motor buses (gasoline-powered buses). Buses were cheaper to run and more flexible because they didn't need tracks. Also, by using buses, the company no longer had to pay to maintain the streets where its tracks used to be.

By early 1949, Denver Tramway had 131 streetcars, 138 trolley coaches, and 116 gasoline buses. By the end of 1950, streetcars were no longer used. Most of the streetcar tracks and wires were removed within five years. Trolley bus service also ended in 1955.

Cars became a bigger part of life for people in Denver. The Denver Tramway Company, which had a monopoly on public transport, wasn't expanding fast enough. More people started using cars to get around. By 1970, Denver had more cars per person than any other place in the country. This was partly because there weren't many public transport choices.

From 1969 to 1971, the Denver Tramway Company continued service with help from the City and County of Denver. In 1971, with old equipment and low ridership, the Denver Tramway Company gave all its assets to the city-owned Denver Metro Transit.

Denver Metro Transit soon faced financial problems. In July 1974, it became part of the Regional Transportation District (RTD). RTD was created to run public transit in the wider Denver-Boulder area.

Many years later, in 1994, rail-based public transport returned to Denver. This happened with the opening of the new D Line light rail system.

How the Tramway Worked

Power and Vehicles

At first, the streetcars got their electricity from small power plants. As the system grew, more electricity was needed. In 1901, a separate company was formed to build and run power plants. The Denver Tramway Company Powerhouse was built between 1901 and 1904. It became the main source of electricity for Denver's streetcars until the 1950s. Today, this old powerhouse is an REI store.

The Denver Tramway Company used 39-foot long trolley cars. Some were built by the company itself, but most came from the Woeber Auto Body and Manufacturing Company.

There were two main types of cars. Type 1 cars could only go in one direction. They had an entrance in the middle on the right side. Type 2 cars could be reversed, so they had controls at both ends and entrances on both sides. The trolley cars had a special look. They were painted "Coach Painter’s Red" on the main part and "Dark Straw" (yellow) on the lower parts. During busy times, unpowered trailers could be pulled behind the trolleys to carry more passengers.

Not many of the original trolley cars from the system have been saved. After streetcars were replaced by buses after World War II, the Denver Tramway Co. sold the old trolleys for only $100 each. One passenger car, No. 54, is now inside the old Denver City Cable Railway’s powerhouse. This building used to be an Old Spaghetti Factory restaurant.