Detroit Industry Murals facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Lua error in Module:Wikidata at line 560: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value). |

|

|---|---|

| Lua error in Module:Wikidata at line 560: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value). | |

Script error: The function "getImageLegend" does not exist.

|

|

| Lua error in Module:Infobox_mapframe at line 185: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value). | |

| Artist | Script error: The function "getPreferredValue" does not exist. |

| Year | Lua error in Module:Wd at line 1575: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value). |

| Medium | Script error: The function "getPreferredValue" does not exist. |

| Movement | Script error: The function "getPreferredValue" does not exist. |

| Subject | Script error: The function "getPreferredValue" does not exist. |

| Dimensions | × × × |

| Designation | Script error: The function "getPreferredValue" does not exist. |

| Location | {{#Property:P17|from= }} Lua error in Module:EditAtWikidata at line 29: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value). |

| Coordinates | Lua error in Module:Coordinates at line 614: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value). |

| Owner | Script error: The function "getPreferredValue" does not exist. |

| Commissioned by | Script error: The function "getPreferredValue" does not exist. |

| Collection | Script error: The function "getPreferredValue" does not exist. |

| Accession No. | Script error: The function "getPreferredValue" does not exist. |

| Preceded by | Script error: The function "getPreferredValue" does not exist. |

| Followed by | Script error: The function "getPreferredValue" does not exist. |

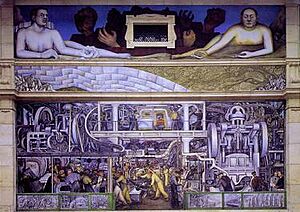

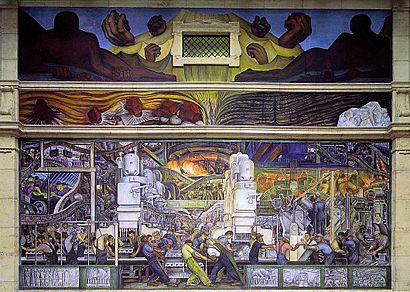

The Detroit Industry Murals are a famous series of paintings by the Mexican artist Diego Rivera. These paintings are called frescoes because they were painted directly onto wet plaster walls. There are twenty-seven panels in total, and they show scenes of industry and work at the Ford Motor Company in Detroit.

These amazing murals surround a special room called the Rivera Court inside the Detroit Institute of Arts. Diego Rivera painted them between 1932 and 1933. He thought they were his best work ever. In 2014, the Detroit Industry Murals were named a National Historic Landmark, which means they are very important to the history of the United States.

The two biggest murals are on the North and South walls. They show workers busy at Ford's huge River Rouge Plant. Other panels show new ideas and progress in science, like medicine and technology. Together, all the murals share the idea that everything we do and think is connected.

Contents

How the Murals Were Ordered

In 1932, Wilhelm Valentiner, who was the director of the Detroit Institute of Arts, asked Diego Rivera to create these murals. He wanted Rivera to paint 27 fresco murals showing the industries of Detroit right inside the museum's courtyard.

Rivera was chosen because he had just finished a mural in California that showed how skilled he was as a painter. It also showed his interest in the modern factories and culture of the United States. The museum agreed to pay for all the materials needed for the murals. Rivera would pay his assistants from the money he received for his art. Edsel Ford, who was the son of Henry Ford, gave $20,000 to help make this project happen.

Here's what Wilhelm Valentiner wrote to Rivera about the project:

to help us beautify the museum and give fame to its hall through your great work...The arts commission will be very glad to have your suggestions of the motifs, which could be selected after you are here. They would be pleased if you could possibly find something out of the industry of the town; but at the end they decided to leave it entirely to you, what you think best to do.

Creating the Murals

Rivera began the project by visiting the Ford River Rouge Complex. He spent three months exploring all the different parts of the factories. During this time, he made hundreds of sketches and ideas for the murals. He even had a photographer, W. J. Stettler, who was Ford's official photographer, help him find visual references.

Rivera was truly amazed by the advanced technology and modern ways of Detroit's factories. He was very interested in the car industry. But he also wanted to learn about the medicine industry. So, he spent time at the Parke-Davis pharmaceutical plant in Detroit to do research for his art at the DIA.

Rivera finished all 27 murals in just eight months. This was a very short time for such a huge and detailed project! To get it done, Rivera and his assistants worked incredibly hard. They often worked fifteen hours a day without breaks. Rivera even lost 100 pounds because of the tough work. He was known for not paying his assistants very well, and at one point, they even protested for higher pay during the project.

Rivera started painting in 1932, during a difficult time called the Great Depression. In Detroit, many people were out of work. Workers at the Ford Motor Company were asking for better pay and working conditions. About 6,000 workers went on strike, but their efforts faced challenges. There were conflicts, and some workers were hurt. Rivera was likely inspired by this intense atmosphere of protest against powerful industries.

During this time, Detroit had a very advanced industrial economy. It was home to the biggest manufacturing industry in the world. In 1927, the Ford Motor Company was making big technological improvements to its assembly line. One of these was a revolutionary automated car assembly line. The Detroit car industry was "vertically integrated." This means they could make every single part for their cars themselves. This was seen as an amazing industrial achievement back then.

Detroit also had factories that made many other things, like steel, electricity, and cement. Even though it was famous for making cars, Detroit also built ships, tractors, and airplanes. Rivera wanted to show this impressive, connected industrial center in his artwork at the Detroit Institute of Art. This series of paintings later became known as the Detroit Industry Murals.

North and South Walls

The two largest murals Rivera painted are on the north and south walls of the interior court, which is now called the Rivera Court. These murals show the workers at the Ford River Rouge Complex in Dearborn, Michigan.

These two big murals are considered the most important parts of the story Rivera told across all 27 panels. The north wall puts the worker in the center. It shows how Ford's famous 1932 V8 engine was made. This mural also explores the connection between people and machines. In a time of machine production, people often thought about the line between humans and machines. Machines were made to act like humans, and humans had to work with machines. Workers and leaders were concerned about fair rights for the working class.

Rivera also included images of huge furnaces that made iron, foundries making molds for parts, conveyor belts carrying parts, and machines doing different jobs. He showed the entire manufacturing process on the large north wall mural. On the right and left sides, he painted the chemical industry. He showed scientists making chemicals for different uses, some helpful and some harmful.

On the south wall, Rivera shows how the outside parts of cars are made. He focuses on technology as a key part of the future. He uses a huge parts-pressing machine in the mural to symbolize this idea. This machine is meant to represent the creation story of the Aztec goddess Coatlicue.

In Aztec mythology from Mexico, Coatlicue was the mother of the gods. She gave birth to the moon, stars, and Huitzilopochtli, the god of the sun and war. The story of Coatlicue was very important to the Aztecs. It showed how complex their culture and religious beliefs were. Some art experts think Rivera compared this Aztec story with the importance of modern technology. Technology had become so important that some people supported it as strongly as a new religion that promised a better future for everyone.

Why the Murals Became Famous

Rivera was a debated choice for this art project because he was known to have ideas about how society and work should be organized that some people disagreed with. The Great Depression had made many people in the U.S. lose faith in industrial and economic progress. Some critics thought the murals were promoting these ideas.

When the murals were finished, the Detroit Institute of Arts invited religious leaders to see them. Some Catholic and Episcopalian leaders said the murals were disrespectful. The Detroit News newspaper said they were "vulgar" and "un-American." Because of all this discussion, 10,000 people visited the museum on one Sunday, and the city even gave the museum more money!

One part of the North wall mural shows a child figure with golden hair, like a halo. On one side is a horse, and on the other is an ox. Below them are several sheep, like in traditional Christmas scenes. A doctor acts like Joseph and a nurse acts like Mary. Together, they are giving the child a vaccination. In the background, three scientists, like the biblical Magi, are doing a research experiment. This part of the fresco is clearly a modern version of traditional images of the holy family. However, some critics thought it was making fun of the idea rather than honoring it.

Some art historians have suggested that Rivera's supporter, Edsel Ford, might have encouraged the controversy. This was perhaps to get more attention for the artwork. An exhibit at the DIA in 2015 explored this idea.

When this specific panel was first shown, it upset some religious people in Detroit so much that they demanded it be destroyed. But Edsel Ford and DIA Director Wilhelm Valentiner stood firm. The panel is still there today.

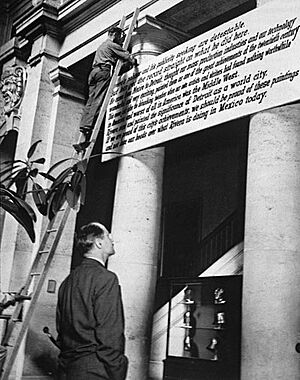

In the 1950s, the DIA put up a sign above the entrance to the Rivera Court. It said:

Rivera's politics and his publicity seeking are detestable. But let's get the record straight on what he did here. He came from Mexico to Detroit, thought our mass production industries and our technology wonderful and very exciting, painted them as one of the great achievements of the twentieth century. This came after the debunking twenties when our artists and writers found nothing worthwhile in America and worst of all in America was the Middle West. Rivera saw and painted the significance of Detroit as a world city. If we are proud of this city's achievements, we should be proud of these paintings and not lose our heads over what Rivera is doing in Mexico today.

See also

In Spanish: Murales de la Industria de Detroit para niños

In Spanish: Murales de la Industria de Detroit para niños

| Frances Mary Albrier |

| Whitney Young |

| Muhammad Ali |