District of Columbia retrocession facts for kids

The District of Columbia retrocession is about giving back land that was originally given to the federal government of the United States. This land was meant to create a special area for the new national capital, the City of Washington. In 1790, the states of Virginia and Maryland gave this land to the federal government.

After many discussions and approvals, the part of the land from Virginia was given back in March 1847. This act of giving land back is called "retrocession." The part of the land from Maryland is still the District of Columbia today. However, people have often suggested giving it back to Maryland, either partly or entirely. This idea usually comes up to help residents of the District of Columbia get full voting rights.

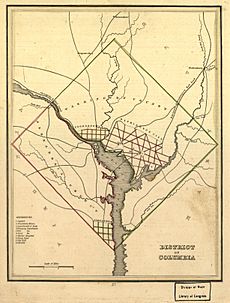

The creation of the District of Columbia was based on a rule in the U.S. Constitution. But it has always been a topic of debate, both for people living there and those outside. The District was originally 100 square miles (259 km2; 25,900 ha) of land. It was given by Maryland and Virginia and was located on both sides of the Potomac River.

In 1801, the Organic Act placed these areas under the control of the United States Congress. This meant that residents lost their right to vote in federal elections. The part of the land west of the Potomac, from Virginia, was 31 square miles (80 km2; 8,029 ha). It included the city of Alexandria, Virginia and a rural area called Alexandria County, D.C..

After many years of debate about residents not being able to vote and concerns about Congress not paying enough attention, this Virginia part of the District was returned in 1847. The remaining District then became its current size of 68.34 square miles (177.00 km2; 17,699.98 ha) east of the Potomac.

Later ideas to return the rest of the District of Columbia to Maryland are seen as a way to give residents full voting representation in Congress. It would also give them more local control over their area. However, people who support D.C. becoming a state say that the Maryland government might not want to take D.C. back.

Contents

Why Was the District of Columbia Created?

The Organic Act of 1801 officially set up the District of Columbia. This law put the federal territory under the direct control of Congress. The District was divided into two counties: Washington County on the east side of the Potomac River, and Alexandria County on the west side.

The cities of Alexandria and Georgetown kept their own local governments. The City of Washington was newly formed within Washington County.

What Happened to Residents' Rights?

After the 1801 Act, people living in the District were no longer considered residents of Maryland or Virginia. This meant they lost their right to vote for members of Congress. They also lost their ability to have a say in changes to the Constitution and their full local self-governance. Since then, residents of the District and nearby states have looked for ways to fix these issues. The most common ideas have been retrocession, making D.C. a state, new federal laws, or changing the Constitution.

While not having a vote in Congress is a big concern, limited local control has also been a major reason for retrocession movements. In 1801, the leaders of Washington County and Alexandria County were all chosen by the President. The mayor of Washington City was also appointed by the President from 1802 to 1820. Other officials, like marshals and attorneys, were also appointed by the President.

When the District's government was combined into one in 1871, people again lost the right to elect their leaders. From 1871 until 1975, the District was run by a governor or commissioners appointed by the President.

In 1975, the District's government was changed again. Citizens were allowed to elect their own mayor and city council members. However, all local laws still had to be reviewed by Congress. Congress has used this power to block some local laws. Congress also has other special powers over the District. For example, it limits the height of buildings in D.C. It also prevents the District from calling its mayor a "governor" or from charging a tax on people who commute into the city for work. Congress also decides who serves on local courts, and all judges are appointed by the President.

Federal groups like the National Capital Planning Commission and the Commission of Fine Arts (CFA) also have a lot of power in the District. Local residents have only a small say in the NCPC, and no say at all in the CFA.

Early Ideas to Return Land

Almost immediately after the 1801 Organic Act, Congress started discussing ideas to return the land to the states. Several bills were proposed in the early 1800s, but none passed. Members of Congress suggested retrocession because they felt it was wrong that District residents couldn't vote. They debated whether the District could be returned without the approval of residents and the state governments of Maryland and Virginia. Some lawmakers even argued that Congress didn't have the power to return the land at all.

After the White House and Congress were burned during the War of 1812, some people wanted to move the capital elsewhere. This made the calls for retrocession less frequent for a while.

By 1822, District citizens again wanted a different political situation. A group in Washington City asked Congress to either make the area a territory or give it back to Maryland and Virginia. That same year, bills were introduced to return Georgetown to Maryland and Alexandria to Virginia.

Virginia Gets Its Land Back

Ideas to reunite the southern part of the District with Virginia had been around since 1803. But it wasn't until the late 1830s that these ideas gained strong local support. In fact, people from Alexandria had actually protested the 1803 effort to return their land. Early efforts, supported by the Democratic-Republicans, focused on the lack of local control. These efforts often included returning some or all of the land north of the Potomac as well. The desire for retrocession grew in the 1830s, leading to Alexandria County being returned in 1847.

Growing Support in Alexandria

The first local push for retrocession began in 1818. The Grand Jury for Alexandria County voted for retrocession and formed a committee to work on it. Similar feelings in Georgetown and other areas led to some small changes. For example, residents of Washington City were allowed to elect their own mayor. But in Alexandria, this didn't stop the unhappiness. After a debate in local newspapers in 1822, the Grand Jury again voted for retrocession.

In 1824, Thomson Francis Mason, who would later become mayor of Alexandria, held a meeting where retrocession was discussed. A petition supporting retrocession with 500 names was sent to Congress. However, a competing group also sent a letter protesting it. Congress did not act on the matter, and the idea faded for a while.

In 1832, Philip Doddridge, a Congressman in charge of the District of Columbia Committee, asked the Alexandria Town Council if they wanted retrocession, a delegate in Congress, or a local District legislature. A vote was held, and 437 people voted for no change, while 402 voted for retrocession. People from outside Alexandria City strongly voted for retrocession.

In 1835, the Alexandria Common Council asked Congress to consider retrocession, but nothing happened.

Slavery and Economic Concerns

In 1836, when the idea of ending slavery in the District was brought up, Senator William C. Preston suggested returning the entire District to Maryland and Virginia. He wanted to "relieve Congress of the burden of repeated petitions on the subject" of slavery. However, neither the effort to end slavery nor the retrocession bill passed that year.

In 1840, retrocession gained new attention. The banks in the District of Columbia asked Congress to renew their charters. When this failed, and the banks had to close, Alexandria held a town meeting. They decided to pursue retrocession. Around 700 people signed a petition for retrocession, with only 12 against it. On October 12, the vote in Alexandria was overwhelmingly for retrocession (666 to 211). However, the vote in the county outside the town (now Arlington) was strongly against it (53 to 5). Even so, the effort paused for a time.

In 1844, John Campbell of South Carolina proposed returning the entire District to Maryland and Virginia. He wanted to prevent people who wanted to end slavery from doing so in the District. But his proposal was never considered.

The Final Push for Retrocession

In early 1846, Alexandria Common Council member Lewis McKenzie restarted the retrocession movement. He suggested sending the results of the 1840 pro-retrocession vote to Congress and the Virginia legislature. This was approved. Two weeks later, Virginia agreed to accept Alexandria County if Congress approved.

The retrocession idea then moved to the U.S. Congress. Alexandria leaders asked Congress for both retrocession and help with their debt from the Canal. Many people thought that voting for retrocession meant Congress would pay Alexandria's debt. However, the House of Representatives decided to separate the issues and dropped the debt relief entirely to get the bill passed.

On February 22, the House passed a bill to return the southern portion of the District. During the debate, some worried if retrocession was allowed by the Constitution. The bill passed by a vote of 95 to 66.

Before the Senate vote, those against retrocession gathered over 150 signatures. These were people who had expected debt relief or who would not be allowed to vote under the House bill. The Washington City Board of Aldermen also opposed the retrocession of Alexandria. The Senate passed the retrocession bill on July 2 by a vote of 32 to 14. President James K. Polk signed it into law on July 9, 1846.

The Referendum and Return

A public vote (referendum) on retrocession was held on September 1-2, 1846. Before the vote, public debates were held. The residents of Alexandria County voted in favor of retrocession, 763 to 222. However, people in the county outside Alexandria City voted against it, 106 to 29. President Polk confirmed the vote and announced the transfer on September 7, 1846.

With the President's announcement, Virginia officially gained control of Alexandria County. The local newspaper, the Alexandria Gazette, quickly changed its masthead to show "Alexandria, Virginia." However, the Virginia legislature did not immediately accept the retrocession. They were concerned that the people of Alexandria County had not been properly included in the process. After months of debate, the Virginia General Assembly formally accepted the retrocession on March 13, 1847. A celebration was held on March 20.

Why Did Alexandria Want to Leave D.C.?

The movement for retrocession was mainly driven by Congress not managing the area as residents wished. Merchants also believed that retrocession would be good for business. Several factors helped the move to return the area to Virginia:

- Economic Decline: Alexandria's economy was struggling because Congress didn't pay enough attention to it. Alexandria needed better transportation to compete with other ports like Georgetown. Congress members from other parts of Virginia sometimes blocked funding for projects like the Alexandria Canal. Returning Alexandria to Virginia allowed residents to find money for projects without Congress's interference.

- Federal Buildings Location: A rule from 1791 said that government buildings could only be built on the Maryland side of the Potomac River. This meant important federal buildings like the White House and the United States Capitol were in Washington, D.C. This made Alexandria less important to the national government.

- Slavery Concerns: At the time, Alexandria was a major center for the slave trade. Rumors spread that people who wanted to end slavery in Congress were trying to stop it in the nation's capital. This could have hurt Alexandria's economy, which relied on slavery.

- Political Representation: If Alexandria returned to Virginia, it would add two more representatives to the Virginia General Assembly.

The free Black population, who were not allowed to vote, strongly opposed retrocession. This was because Virginia had much stricter laws that limited their movement and property rights and required them to carry special papers. Many free Black people left Alexandria. Their numbers dropped by a third, from 1,962 in 1840 to 1,409 in 1850.

One argument against retrocession was that the federal government used Alexandria for military purposes, a signal corps site, and a cemetery. The the Pentagon, the national military headquarters, was not built until about a century later.

Confirming the fears of pro-slavery Alexandrians, the Compromise of 1850 later outlawed the slave trade in the District, although slavery itself was still allowed.

Later Attempts to Undo Retrocession

In later years, there were several attempts to reverse or undo the retrocession, but none succeeded. At the start of the Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln suggested restoring the original borders for security reasons, but the Senate rejected this idea. In 1866, Senator Benjamin Wade proposed a law to undo retrocession, arguing that the Civil War showed it was necessary for the Capital's defense.

In 1873 and again in 1890, some Alexandria residents asked Congress to reverse retrocession. They were concerned about state taxes or believed it was unconstitutional. In 1909, Congressman Everis A. Hayes introduced a bill to return Alexandria County (except the towns of Alexandria and Falls Church) to the District of Columbia. However, the committee did not support it, even though President Taft wanted the District to be larger.

What Were the Consequences?

In 1850, after retrocession was complete, Virginia asked the federal government to return $120,000 that Virginia had given to help build public buildings. Congress agreed, despite some objections.

Was It Constitutional?

The legality of retrocession has been questioned. The Contract Clause in the Article One of the United States Constitution says that states cannot break contracts they are part of. By taking Alexandria back in 1846, Virginia arguably broke its promise to "forever cede and relinquish" the territory for the U.S. government's permanent home. President William Howard Taft also believed the retrocession was unconstitutional and tried to have the land returned to the District.

The Supreme Court of the United States never gave a clear opinion on whether the retrocession of the Virginia part of the District of Columbia was constitutional. In the case of Phillips v. Payne (1875), the Supreme Court said that Virginia had actual control over the area returned by Congress in 1846. However, the court did not rule on the main constitutional question of retrocession.

The United States Circuit Court of the District of Columbia had previously ruled that retrocession was constitutional in the case Sheehy vs. the Bank of the Potomac (1849).

Ideas to Return Maryland's Land

Federal bills to reunite the northern part of the District with Maryland have been around since 1803. But unlike the southern part, local residents almost always voted against it when given the choice. In 1826, an informal vote on retrocession for Georgetown passed by only one vote. But because so few people voted, it was decided that the general public didn't support it. As mentioned earlier, in 1836, Senator William C. Preston proposed returning the entire District to Maryland and Virginia to avoid debates about slavery in the District. In 1839, some members of Congress suggested returning the part of the District west of Rock Creek to Maryland.

In the 21st century, some members of Congress, like Rep. Dan Lungren, have suggested returning most parts of the city to Maryland. Their goal is to give District of Columbia residents voting representation and control over their local affairs. These attempts, mostly supported by Republicans, have failed.

Proposals dating back to the 1840s would handle retrocession north of the Potomac River similarly to how it was done south of it. This would mean the land would return to Maryland after approval from Congress, the Maryland legislature, and local voters. The difference would be that a small area immediately around the United States Capitol, the White House, and the Supreme Court building would remain a federal district. This small area would be called the "National Capital Service Area." The idea to return all but the federal lands to Maryland goes back to at least 1848.

What Are the Challenges?

One challenge with retrocession is that the state of Maryland might not want to take the District back. According to former Rep. Tom Davis in 1998, returning the District to Maryland without that state's permission might require a change to the Constitution.

Are There Other Ideas?

An alternative idea to retrocession was the District of Columbia Voting Rights Restoration Act of 2004. This bill would have treated District residents as Maryland residents for congressional representation. Maryland's congressional delegation would then have included the population of the District. Supporters of this plan argued that Congress already has the power to pass such a law without constitutional concerns.

From 1790 until 1801, citizens living in D.C. continued to vote for members of Congress in Maryland or Virginia. Legal experts suggest that Congress has the power to restore those voting rights while keeping the federal district intact. However, this proposed law never moved forward in Congress.

How Much Support Do These Ideas Have?

Most residents of Maryland and the District of Columbia do not support retrocession. A 1994 study showed that only 25% of suburban residents surveyed supported retrocession to Maryland. This number dropped to 19% among District residents. A 2000 study confirmed this opposition, with only 21% of those surveyed supporting retrocession. A 2016 poll of Maryland residents showed that only 28% supported taking in the District of Columbia, while 44% were against it.

From 1993 until 2009, neither statehood nor retrocession was a major legislative goal for either political party. Supporters of D.C. voting rights focused on a partial solution, giving D.C. one House member. But in 2014, efforts to make D.C. a state began again. This led to the 2016 Washington, D.C. statehood referendum. In March 2019, a bill supporting statehood passed the House of Representatives. Then, on June 26, 2020, the House voted to admit the state of Washington, Douglass Commonwealth, which would include most of the District of Columbia. This was the first time a statehood bill for the District passed either chamber of Congress.

Images for kids

| Ernest Everett Just |

| Mary Jackson |

| Emmett Chappelle |

| Marie Maynard Daly |