Dorian invasion facts for kids

The Dorian invasion is a big idea that historians use to explain why the way people spoke and lived in Southern Greece changed a long time ago. Before this change, people spoke older Greek dialects. After, they spoke new ones, which ancient Greek writers called "Dorian." These new ways were named after the Dorians, a group of people who spoke these dialects.

Ancient Greek stories say that the Dorians took over a region called the Peloponnesus. They called this event the Return of the Heracleidae. This means the return of the descendants of the hero Heracles. In the 1800s, scholars thought this legend might be a real event. They named it the Dorian invasion.

Over time, the meaning of "Dorian invasion" has changed. Historians, language experts, and archaeologists have used it to try and understand big changes in culture. For example, how Dorian culture appeared on islands like Crete is still a bit of a mystery.

Even after almost 200 years of study, we don't have solid proof that a huge group of Dorians moved into Greece. We also don't know where the Dorians originally came from. Archaeologists haven't found clear evidence of such an invasion. However, because the Dorians are mentioned so much in old writings, most historians still consider the idea. Some experts even connect the Dorians or the people they affected with the mysterious Sea Peoples. These groups appeared during a time of big changes around 1200 BC, known as the Late Bronze Age collapse. The idea of the "Dorian invasion" helps explain the cultural and economic problems that happened after the Mycenaean period and led into the Greek Dark Ages.

Contents

Return of the Heracleidae

Old Greek stories, like those written by Herodotus, talk about the "Return of the Heracleidae". These were the children and grandchildren of the hero Heracles. After Heracles died, his family was sent away. But generations later, they came back to take control of the Peloponnesus, a region Heracles had once ruled.

The main leaders of the Heraclids were two brothers, Kresphontes and Temenos, and two twins, Eurysthenes and Prokles. They were all descendants of Heracles. They split most of the Peloponnesus into three parts. Kresphontes took Messenia, Temenos took the northeast, and the twins took Laconia. This is how the twins became the first two kings of Sparta.

The Greece mentioned in these stories is the mythical one, which we now think of as Mycenaean Greece. The details of the stories change a bit between different ancient writers. But the main idea is that ruling families claimed their right to rule came from Heracles.

The Greek words for the Dorians' arrival mean "to descend" or "come down." It can mean coming down from mountains to lowlands, or like a flood or wind sweeping down. This idea of sweeping down onto the Peloponnesus led to the English translation "invasion."

The Heracleidae and the Dorians were not exactly the same. Historian George Grote explained their connection. He said that Heracles helped the Dorian king Aegimius in a fight. In return, Aegimius gave Heracles a part of his land and adopted Heracles' son, Hyllus.

After Heracles died, his son Hyllus was forced out of Mycenae by a rival. This rival, Eurystheus, later died trying to invade Attica. With Eurystheus's family gone, only the Heraclids were left from that royal line.

Another family, the Pelopids, then took power. The Heraclids tried to get their lands back but were defeated. Hyllus then made a deal: peace for three generations in exchange for a single fight. He was killed in this fight.

After this, the Heracleidae decided to claim the Dorian land that Heracles had been given. From then on, the Heraclids and Dorians became very close allies. Three generations later, the Heracleidae, with the help of the Dorians, took over the Peloponnesus. Grote called this a "victorious invasion."

The term "invasion"

The phrase "Dorian invasion" became widely used around the 1830s. Another common term was "Dorian migration." For example, in 1831, Thomas Keightly used "Dorian migration." But by 1838, he was using "Dorian invasion."

Neither word perfectly describes what happened. Both words suggest an attack from outside a society. But the Dorians were already part of Greece and Greek society. An earlier historian, William Mitford, described a "Dorian conquest" that caused a huge change in the Peloponnesus. He said that almost nothing was left the same, except for the rugged area of Arcadia.

In 1824, Karl Otfried Müller's book "Die Dorier" was published in German. When it was translated into English in 1830, the translators used terms like "the Doric invasion." This was to translate Müller's "Die Einwanderung von den Doriern," which literally means "the migration of the Dorians." Müller's idea was different from a simple invasion.

Müller's "Einwanderung" meant something similar to the "Return of the Heracleidae." But Müller also connected it to the idea of "Völkerwanderung," which referred to the large migrations of Germanic tribes. Müller studied languages to understand this. He thought that the first people in Greece, called Pelasgians, were Hellenic (Greek). He believed that the original Pelasgian language was the ancestor of both Greek and Latin.

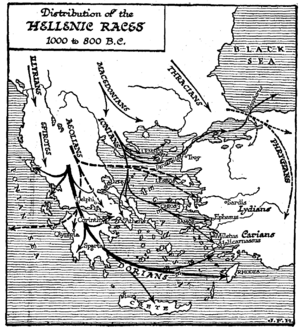

Müller suggested that this language became Proto-Greek. He thought it was changed in Macedon and Thessaly by invasions from other groups. He believed that this pressure pushed out Greek speakers in three waves: first Achaean (including Aeolian), then Ionian, and finally Dorian. This idea helped explain how different Greek dialects were spread in classical times.

Following this idea, language expert Albert Thumb noticed something interesting. In the Peloponnesus and on the islands where the Dorians settled, their dialect had parts of the Arcadian dialect. This could mean that the Dorians conquered an earlier population. These people were then pushed into the Arcadian mountains. In places where Dorians were a smaller group, like Boeotia, the dialects were mixed. Or, the Dorians adopted the local dialect, as in Thessaly.

The Achaeans, mentioned by Homer, spoke the Aeolic-Arcadian dialect across eastern Greece, except for Attica, where the Ionians lived. Some modern scholars think that "Achaeans" might not have been a real group but a name created in epic poems. They believe the term was redefined later. The Ionians are thought to be the very first wave of Greek migration.

In 1902, K. Paparigopoulos called the event the "Descent of the Heraclidae." He said the Heraclidae came from Thessaly after being forced out by people living in Epirus.

Greeks from outside Greece

Towards the end of the 1800s, the language expert Paul Kretschmer argued strongly that the Pelasgian language was an older language spoken in Greece before Greek. He thought it might be from Anatolia (modern Turkey). This idea meant that Müller's early Greeks didn't have a homeland within Greece. Kretschmer didn't suggest the Heracleidae or their Dorian allies came from Macedon or Thessaly. Instead, he thought the earliest Greeks came from the plains of Asia. He believed the Proto-Indo-European language (the ancestor of many languages, including Greek) broke up there around 2500 BC.

Kretschmer suggested that somewhere between Asia and Greece, a new home for Greek tribes developed. From there, he thought Proto-Ionians came around 2000 BC, Proto-Achaeans around 1600 BC, and Dorians around 1200 BC. He imagined them sweeping down on Greece in three waves.

Kretschmer was sure that if the unknown homeland of the Greeks wasn't known yet, archaeology would find it. From then on, history books talked about Greeks entering Greece. As late as 1956, J.B. Bury's "History of Greece" still mentioned an "invasion which brought the Greek language into Greece." For 50 years, archaeologists looked for the Dorians further north than Greece. This idea was also linked to the belief that the Sea Peoples were part of the same north-south migration around 1200 BC.

The problem with this theory is that it needed both an "invaded" Greece and an outside area where Greek developed. While there was plenty of evidence for the "invaded" Greece, there was no evidence at all for this outside homeland. Similarly, a clear Greek homeland for the Sea Peoples never appeared. So, scholars kept looking for the Dorians in other places. By the 1960s, the idea of Greek developing outside of Greece was becoming less popular.

Greek origin in Greece

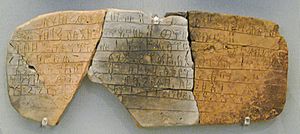

More progress in understanding the Dorian invasion came from reading Linear B inscriptions. Linear B is an ancient writing system. The language in these texts is an early form of Greek called Mycenaean Greek. By comparing it with later Greek dialects, scholars could see how the dialects developed from Mycenaean Greek. For example, the classical Greek word anak-s (king) was thought to come from an older form *wanak-. In Linear B texts, we find wa-na-ka (king) and wa-na-sa (queen).

Ernst Risch quickly suggested that there was only one migration that brought Proto-Greek into Greece. Proto-Greek is believed to be the earliest form of all known Greek languages. He thought it then split into different dialects *within* Greece. However, linguists who worked on deciphering Linear B had doubts about classifying Proto-Greek. John Chadwick wrote in 1976 that Greek might not have existed before 2000 BC. He thought it was formed in Greece by mixing a local population with invaders who spoke another language.

Vladimir I. Georgiev suggested that the Proto-Greek region was in northwestern Greece. By the end of the 20th century, the idea of an invasion by outside Greek speakers was no longer the main view. Geoffrey Horrocks wrote that Greek is now widely believed to be the result of contact between Indo-European immigrants and local languages in the Balkan peninsula starting around 2000 BC.

If the different dialects developed within Greece, then no later invasions were needed to explain their presence.

Destruction at the end of Mycenaean IIIB

Meanwhile, archaeologists found evidence of many Mycenaean palaces being destroyed. For example, the Pylos tablets recorded sending "coast-watchers." Not long after, the palace was burned, probably by invaders from the sea. Carl Blegen, an archaeologist, believed that the "fire-scarred ruins" of all the great palaces showed the path of the Dorians. He dated this destruction to around 1200 BC.

However, blaming the Dorians for this destruction has its own problems. Around the same time, the Hittite empire in Anatolia collapsed. Also, Egypt faced invasions from the Sea Peoples. Some theories suggest that the Sea Peoples caused the ruin in the Peloponnesus. Evidence from the Linear B tablets at Pylos, mentioning sending people to the coast, might be from when the Egyptian pharaoh expected enemies.

The identity of these enemies remained a question. Some evidence suggests that some Sea Peoples might have been Greek. But most destroyed Mycenaean sites are far from the sea. Also, the expedition against Troy at the end of this period shows that the sea was safe.

Historian Michael Wood suggests we should still consider the old stories. He says they tell us about constant rivalries between the royal families of the Heroic Age. This means the Mycenaean world might have fallen apart due to "feuding clans of the great royal families." The idea of internal struggles had been considered for a long time.

John Chadwick, after looking at different ideas, suggested in 1976 that there was no Dorian invasion. He thought the palaces were destroyed by Dorians who had been living in the Peloponnesus all along as a lower class (like slaves). He believed they were staging a revolution. Chadwick also thought that northern Greek was an older, more traditional language, and southern Greek developed as a palace language under Minoan influence.

Another scholar, Mylonas, combined some of these ideas. He thought that some events in Argolis and attempts to rebuild after 1200 BC could be explained by both internal fighting and pressure from enemies, like the Dorians. Even if the Dorians were one cause of the Bronze age collapse, they also brought new cultural elements. It seems that Dorian groups moved south slowly over many years. They caused damage until they managed to settle in the Mycenaean centers.

Invasion or migration

After the Greek Dark Ages, most people in the Peloponnesus spoke Dorian. But evidence from Linear B and old stories like Homer's poems suggests that people had spoken Achaean – or Mycenaean Greek – before. Also, society in the Peloponnesus completely changed. It went from states ruled by kings with a palace-based economy to a new system. In Sparta, for example, a Dorian ruling group controlled a caste system.

According to scholar H. Michell, if the Dorian invasion happened around the 12th century BC, we know nothing about them for the next hundred years. Blegen admitted that in the period after 1200 BC, the whole area seemed to have very few people or was almost empty.

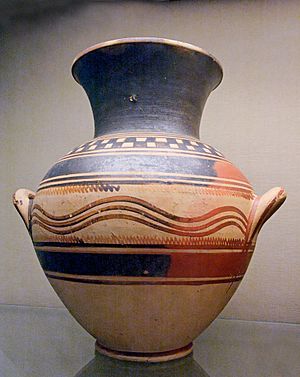

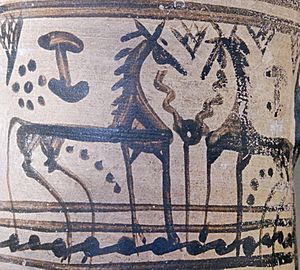

The problem is that there are no signs of Dorians anywhere until the start of the Geometric period around 950 BC. This simple pottery style seems to be connected with other changes in culture. These include the use of iron weapons and changes in burial practices. Mycenaeans buried groups of people in large tombs, but now people were buried individually, and cremation was used. These changes can definitely be linked to the historical Dorian settlers, like those in Sparta in the 10th century BC. However, these changes happened all over Greece. Also, the new iron weapons would not have been used in 1200 BC.

Scholars faced a puzzle: an invasion at 1200 BC but settlement at 950 BC. One idea is that the destruction of 1200 BC was not caused by the Dorians. And that the mythical return of the Heracleidae is linked to the settlement at Sparta around 950 BC. It's possible that the destruction of Mycenaean centers was caused by wandering northern people (Dorian migration). They might have destroyed palaces like Iolcos and Thebes, then crossed the Isthmus of Corinth. They then destroyed Mycenae, Tiryns, and Pylos, and then returned north. However, Pylos was destroyed by a sea attack. The invaders didn't leave behind weapons or graves. And it's hard to prove that all sites were destroyed at the same time. It's also possible that Dorian groups moved south slowly over many years, causing damage, until they managed to settle in the Mycenaean centers.

Closing the gap

The search for the Dorian invasion began to explain the differences between the Peloponnesian society described by Homer and the historical Dorians of classical Greece. The first scholars to work on this used Greek legends. Then, language experts took over, but they only made the problem clearer. Finally, archaeologists inherited the issue. Maybe some clear Dorian archaeological evidence will be found that shows exactly how and when Peloponnesian society changed so much.

Historians defined the Greek Dark Ages as a period of general decline. During this time, the palace economy disappeared, leading to a loss of law and order. Writing was lost, trade decreased, and the population shrank. Many settlements were abandoned. There was also a shortage of metals, and the quality of art, especially pottery, declined. In its broadest sense, the Dark Age lasted from 1200 BC to 750 BC. This was when the Archaic or Orientalizing period began. During this time, influences from the Middle East through overseas colonies helped Greece recover.

A Dark Age of poverty, low population, and metal shortages doesn't fit the idea of large groups of successful warriors. These warriors would have had the latest military gear, sweeping into the Peloponnesus to rebuild civilization their way. This Dark Age has three periods of art and archaeology: sub-Mycenaean, Proto-geometric, and Geometric. The most successful, the Geometric period, seems to fit the Dorians better. But there is a gap. This period didn't start only in Dorian territory. It is more connected with Athens, an Ionian state.

Still, the Dorians were part of the Geometric period. So, finding its origin might help find the origin of the Dorians. The Geometric style clearly developed from the Proto-geometric. The logical break in material culture is the start of the Proto-geometric period around 1050 BC. This leaves a gap of 150 years from the 1200 BC destruction. The year 1050 BC doesn't offer anything clearly Dorian either. But if the Dorians were present in the Geometric period, and they weren't always there as a hidden lower class, then 1050 BC is the most likely time they arrived. Cartledge joked that it's a "scandal" that archaeologists haven't found clear evidence of the Dorians. He said they've lost credit for Geometric pottery, cremation burials, iron-working, and even the simple straight pin.

The question remains open for more study.

See also

In Spanish: Invasión dórica para niños

In Spanish: Invasión dórica para niños

- Ancient Greek dialects

- Comparative method

- Doric Greek

- Doris

- Dorus, the eponymous founder

- Greek Dark Ages

- Historical linguistics

- Vedic Period

- Pre-modern human migration

- Indo-European migrations

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |