Edward Alfred Minchin facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

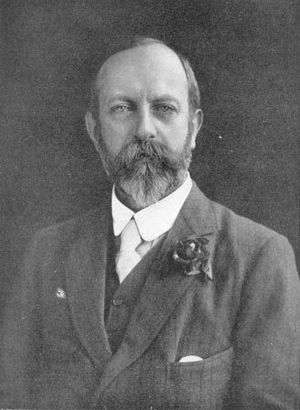

Edward Alfred Minchin

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 26 February 1866 |

| Died | 30 September 1915 (aged 49) |

| Nationality | British |

| Alma mater | Keble College, Oxford |

| Known for | Porifera Trypanosomes |

| Spouse(s) | Florence Maude Fontain (m. 1903) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields |

|

| Institutions | |

| Influences | Edwin Ray Lankester |

Edward Alfred Minchin (born 26 February 1866 – died 30 September 1915) was a British zoologist. He was a scientist who studied animals, especially sponges and very tiny living things called Protozoa. He became a professor at University College London in 1899. Later, he became a professor of Protozoology at the University of London in 1906. In 1911, he was chosen as a Fellow of the Royal Society, which is a big honor for scientists.

Contents

Early Life and Learning

Edward Alfred Minchin was born in a town called Weston-super-Mare on 26 February 1866. His parents were Charles N. Minchin and Mary J. Lugard. He went to school at the United Services College in England. He also studied at the Bishop Cotton Boys' School in Bangalore, India.

Minchin then went to Keble College, Oxford University. In 1890, he graduated with top honors in zoology. Three years later, he became a Fellow of Merton College. This meant he was a special member of the college.

Minchin's Science Career

After finishing university, Edward Minchin received special scholarships. These allowed him to travel across Europe. He worked in different science places, like the Stazione Zoologica in Naples, Italy. He also worked in labs in France and Germany. There, he learned from famous scientists like Otto Bütschli and Richard Hertwig.

Working at Oxford and UCL

When he came back to Oxford, he worked with a scientist named Ray Lankester. Minchin helped teach about animal anatomy from 1890 to 1899. He also taught biology at Guy's Hospital for a short time.

In 1899, Minchin became the Jodrell Professor of Zoology at University College London (UCL). He also became the curator of the Grant Museum of Zoology. While at UCL, Minchin studied sponges. He especially looked at how their tiny, hard parts (called spicules) grew. He was the first to clearly show that sponges are not part of the group called Coelenterata.

Studying Tiny Parasites

Ray Lankester wanted a permanent professor position for studying protozoa. In 1906, this job was finally created at the Lister Institute of Preventive Medicine. Minchin was chosen for this important role. He kept this job until he died in 1915.

At the Lister Institute, Minchin started to focus on parasitic protozoa. These are tiny living things that live inside other animals and can cause diseases. He was very interested in trypanosomes. In 1905, he traveled to Uganda to study sleeping sickness. This is a serious disease caused by trypanosomes. He then studied trypanosomes in humans and other animals like rats and birds.

Books and Other Work

During his life, Minchin wrote about 40 science papers. His very first paper was about the stink glands of cockroaches. He wrote it in 1888, while he was still a student.

Minchin also wrote seven articles for the 1911 edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica. One of these was the entry for Protozoa. In 1912, he published a textbook called An Introduction to the Study of Protozoa. He also helped write chapters for Ray Lankester's big book, Treatise on Zoology.

Science Societies

Edward Minchin was encouraged to join the Royal Society by Ray Lankester. Lankester praised Minchin's work on tsetse flies. Besides being a Fellow of the Royal Society, Minchin was part of other science groups. He was the President of the Quekett Microscopical Club from 1908 to 1912. He was also a Vice-President of the Zoological Society of London. He was the Zoological Secretary of the Linnean Society. In 1910, he won the Linnean Society's Trail Award.

Death and What He Left Behind

Edward Minchin was often sick during his life. He died on 30 September 1915, when he was 49 years old. He passed away from a lung illness called tubercular pleurisy.

After he died, people wrote about his life and work. They praised the excellent quality of his research. They also admired how much he knew about science. Many described him as the first great British scientist to study protozoa.

Images for kids

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |