Elizabeth Fry facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Elizabeth Fry

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born |

Elizabeth Gurney

21 May 1780 Norwich, England

|

| Died | 12 October 1845 (aged 65) Ramsgate, England

|

| Spouse(s) |

Joseph Fry

(m. 1800) |

| Children | 11 |

Elizabeth Fry (born Gurney; May 21, 1780 – October 12, 1845) was an amazing English woman. She worked hard to make prisons better, especially for women. She was also a Quaker, a type of Christian. People sometimes called her the "Angel of Prisons" because she helped so much. She even helped create new laws to improve how prisoners were treated.

Elizabeth Fry was a big reason for the 1823 Gaols Act. This law made sure that men and women prisoners were kept separate. It also meant that women prisoners had female guards.

Important people like Queen Victoria and Russian Emperors Alexander I and Nicholas I of Russia supported her work. She even wrote letters to them and their wives. Because of her achievements, her picture was on the Bank of England £5 note from 2002 to 2016.

Contents

Elizabeth Fry's Early Life and Family

Elizabeth Fry was born in Norwich, England. Her family, the Gurneys, were well-known Quakers. Her childhood home was Earlham Hall, which is now part of the University of East Anglia. Her father, John Gurney, was a partner in a bank called Gurney's Bank. Her mother, Catherine, was from the Barclay family, who helped start Barclays Bank.

Elizabeth's mother died when Elizabeth was only twelve years old. As one of the oldest girls, Elizabeth helped take care of her younger brothers and sisters. This included her brother Joseph John Gurney, who also became a helper of others.

Her Marriage and Children

When Elizabeth was 20, she met Joseph Fry. He was a banker and also a Quaker. They got married on August 19, 1800, in Norwich. They then moved to London. Elizabeth Fry became a minister in the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) in 1811.

Joseph and Elizabeth Fry had eleven children together. They had five sons and six daughters:

- Katharine (Kitty) Fry (1801–1886)

- Rachel Elizabeth Fry (1803–1888)

- John Gurney Fry (1804–1872)

- William Storrs Fry (1806–1844)

- Richenda Fry (1808–1884)

- Joseph Fry (1809–1896)

- Elizabeth (Betsy) Fry (1811–1816), who sadly died young.

- Hannah Fry (1812–1895)

- Louisa Fry (1814–1896)

- Samuel Fry (1816–1902)

- Daniel Fry (1822–1892)

Elizabeth Fry's Work to Help Others

Elizabeth Fry was inspired to help people after hearing a Quaker preacher. In 1813, a family friend, Stephen Grellet, encouraged her to visit Newgate Prison. What she saw there shocked her.

Conditions in Newgate Prison

Newgate Prison was very crowded, especially with women and children. Some prisoners had not even had a trial yet. The cells were small, and prisoners slept on straw. They had to cook and wash in these tiny spaces. Many prisoners were also sent to Australia on ships that Elizabeth Fry thought were like "slave ships."

She was so upset that she returned the next day with food and clothes for some of the prisoners. For a few years, she couldn't continue her work because her family's bank had money problems.

Making Prisons Better

Elizabeth Fry returned to her project in 1816. She managed to get money to start a school inside the prison for children who were locked up with their mothers. Instead of just telling the women what to do, she suggested rules and then let the prisoners vote on them.

In 1817, she helped start the Association for the Reformation of the Female Prisoners in Newgate. This group gave women materials so they could learn to sew and knit. This helped them calm down and also taught them skills they could use to earn money when they left prison. This idea spread, and in 1821, the British Ladies' Society for Promoting the Reformation of Female Prisoners was created.

Elizabeth Fry also believed that prisoners should be helped to become better people, not just punished harshly. Her ideas were adopted by London officials and many other prisons.

The 1823 Gaols Act was passed, partly because of Fry's ideas. This law helped separate male and female prisoners, which was a big step. However, it didn't fix everything. Fry knew this and spoke to a special committee in 1835. She said that many prisons were still "schools for crime" with no teaching or jobs for prisoners. Things only truly improved when the Prisons Act 1835 was passed, which brought all prisons under central control and appointed inspectors.

Helping Prisoners Sent to Australia

In those days, even for small crimes, people could be sentenced to death or sent to Australia. Elizabeth Fry tried to get death sentences changed to deportation. She and other women visited ships carrying female prisoners to Australia. They brought comforts for the long journey and helped make sure the women and children had useful things to do.

Fry fought for the rights of these prisoners. Women were often taken through London in open carts, chained, and people would throw rotten food at them. Fry convinced the prison governor to use closed carriages instead. She also visited the ships and made sure each woman and child got enough food and water. She even arranged for each woman to get sewing materials, a Bible, and useful items like string and cutlery. This way, they could make quilts to sell and have skills when they arrived.

When she heard that female prisoners were left to fend for themselves in Australia, she spoke to the authorities. This led to women's barracks being built in Parramatta, Australia, and proper transport from the port.

Elizabeth Fry visited 106 transport ships and saw 12,000 prisoners. Her work helped lead to the end of sending prisoners to Australia, which officially stopped in 1837. She continued visiting ships until 1843.

Expanding Prison Reform Efforts

Elizabeth Fry wrote a book called Prisons in Scotland and the North of England. In it, she described staying overnight in some prisons to see the conditions herself. She even invited important people to do the same. Her kindness helped her become friends with prisoners, and they started trying to improve their own conditions.

Her brother-in-law, Thomas Fowell Buxton, became a Member of Parliament and helped share her work with other MPs. In 1818, Fry spoke to a committee in the British House of Commons about prison conditions. She was the first woman to speak in that part of Parliament.

Fry's work spread beyond England. In 1818, her friends Stephen Grellet and William Allen traveled to Russia to visit prisons there. They had a letter from Emperor Alexander I, telling his people to help these English Quakers.

In 1827, Fry visited women's prisons in Ireland. She encouraged women in Belfast to start their own group to improve conditions in the poorhouse. Even after her husband had money problems in 1828, her brother helped her continue and expand her work. In 1838, Fry and her husband, along with other Quakers, visited French prisons despite language differences.

Helping the Homeless and Nurses

Elizabeth Fry also helped the homeless. She opened a "nightly shelter" in London after seeing a young boy's body in the winter of 1819–1820. In 1824, she started the Brighton District Visiting Society. This group arranged for volunteers to visit poor homes and offer help. This idea was very successful and was copied in other towns across Britain.

In 1840, Fry opened a training school for nurses. Her program inspired Florence Nightingale, who later took some of Fry's trained nurses to help wounded soldiers in the Crimean War.

Fighting Against Slavery

After the Atlantic slave trade was ended in the British Empire, slavery still existed in other European colonies. Elizabeth Fry actively campaigned for slavery to be abolished in Danish and Dutch colonies.

Her Reputation and Admirers

Many important people admired Elizabeth Fry. Queen Victoria met her several times before she became Queen and gave money to her cause after she took the throne. Robert Peel, a politician, also passed several laws to help her work, including the Gaols Act 1823.

In 1842, Frederick William IV of Prussia, the King of Prussia, visited Fry in Newgate Prison during his trip to Great Britain. He had met her before and was so impressed by her work that he insisted on visiting the prison himself.

Elizabeth Fry's Death and Legacy

Elizabeth Fry died from a stroke in Ramsgate, England, on October 12, 1845. She was buried in the Friends' burial ground in Barking. Sailors in Ramsgate lowered their flag to half-mast to show respect, which was usually only done for a king or queen. More than a thousand people attended her burial.

The Elizabeth Fry Refuge

After her death, people wanted to create a memorial for Elizabeth Fry. Instead of a statue, they decided to open a practical charity. In 1849, the first Elizabeth Fry refuge opened in London. It was a temporary shelter for young women leaving prison or police stations. The refuge taught women skills like laundry and needlework to help them find jobs.

The refuge moved several times and is now located in Reading. The original building in Hackney is now empty, but there are plans to restore it. A plaque at the entrance remembers Elizabeth Fry.

Memorials to Elizabeth Fry

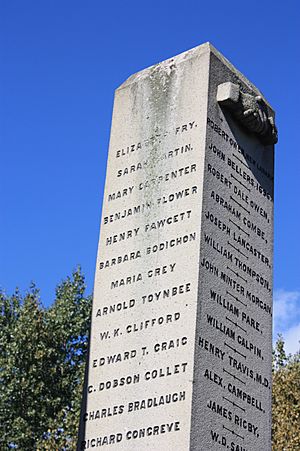

There are many memorials to Elizabeth Fry. Plaques mark her birthplace in Norwich, her childhood home Earlham Hall, her first married home in London, and her final home in Ramsgate. Her name is also on the Reformers Monument in Kensal Green Cemetery in London.

Because of her work, several places related to prisons and justice are named after her. One of the buildings at the Home Office headquarters in London is named after her. There is a bust of her at HM Prison Wormwood Scrubs and a stone statue at the Old Bailey courthouse. The Canadian Association of Elizabeth Fry Societies continues her work by helping women in the criminal justice system. They also celebrate a National Elizabeth Fry Week in Canada every May.

Elizabeth Fry is also remembered in schools and hospitals. The University of East Anglia has a building named after her. There is an Elizabeth Fry Ward at Scarborough General Hospital. A road at Guilford College in North Carolina, founded by Quakers, is named for her. There is a bust of her in East Ham Library in London.

Quakers also honor Elizabeth Fry. Her grave in Barking was restored in 2003. A plaque was put up in her honor at the Friends Meeting House in Norwich in 2007. She is also shown in the Quaker Tapestry, which tells stories of Quaker history. The Elizabeth Fry room at Friends House in London is named after her.

Other Christian groups also remember her. In Manchester's Anglican Cathedral, a window shows Elizabeth Fry among other noble women. The Church of England remembers her on October 12.

From 2001 to 2016, Elizabeth Fry was on the back of the £5 notes issued by the Bank of England. She was shown reading to prisoners at Newgate Prison, with a key representing the prison key she received. In 2016, her image was replaced by Winston Churchill. She was also honored on UK stamps in 1976.

There is a road named after Fry in Johannesburg, South Africa. Her many diaries have been studied to learn more about her life.

Elizabeth Fry's Writings

- (1827) Observations on the visiting, superintendence and government, of female prisoners

- (1831) Texts for every day in the year, principally practical & devotional

- (1841) An address of Christian counsel and caution to emigrants to newly-settled colonies

See also

In Spanish: Elizabeth Fry para niños

In Spanish: Elizabeth Fry para niños

| Calvin Brent |

| Walter T. Bailey |

| Martha Cassell Thompson |

| Alberta Jeannette Cassell |