Federal Theatre Project facts for kids

The Federal Theatre Project (FTP) was a special program that ran from 1935 to 1939. It was created during the Great Depression in the United States to help people find jobs in theatre. It was part of the New Deal, a series of programs designed to help the country recover.

The FTP wasn't just about entertainment. Its main goal was to give jobs to artists, writers, directors, and other theatre workers who were unemployed. Hallie Flanagan, a drama professor, was chosen to lead the project. She helped create a network of regional theatres across the country. These theatres put on plays that were important to people's lives, tried new ideas, and allowed millions of Americans to see live theatre for the very first time.

Even though the Federal Theatre Project used only a tiny part of the money given by the government and was very popular, it faced a lot of political problems. Some people in Congress worried about racial integration and thought the project might have Communist ideas. Because of these concerns, its funding was stopped on June 30, 1939.

Contents

How the Project Started

The Federal Theatre Project was part of the Works Progress Administration (WPA), another New Deal program. It began on August 27, 1935. The WPA received billions of dollars, and a portion of that money, about $27 million, was set aside for artists, musicians, writers, and actors. This was known as Federal Project Number One.

Before the FTP, some government efforts tried to help theatre workers, but they were mostly seen as charity. The Federal Theatre Project was different. It aimed to give real jobs to people in the theatre world. Only those who were officially unemployed but skilled in theatre could get work.

Hallie Flanagan, the director, explained that for the first time, the government wanted to help workers keep their skills and their self-respect. Flanagan was a theatre professor at Vassar College. She had studied how government-supported theatre worked in other countries. Harry Hopkins, who led the WPA, chose her for the job. They had even gone to college together. They picked her because they wanted someone with strong academic knowledge and a broad view, not just someone from the commercial theatre business.

Flanagan faced a huge challenge: creating a national theatre program very quickly to employ thousands of jobless artists. The theatre industry was already struggling before the Great Depression began in 1929. Movies and radio were becoming very popular, and live theatre was losing its audience. Many actors and stage workers had been out of work since movies started replacing live shows around 1914. When sound movies came out, 30,000 musicians lost their jobs.

During the Great Depression, people had little money for fun. They could watch movies for about 25 cents, but live theatre tickets cost much more, from $1.10 to $2.20. This higher price covered theatre rent, advertising, and payments to performers and union workers. Unemployed theatre professionals often had to take any job they could find, no matter how little it paid. Sometimes, charity was their only option.

Harry Hopkins told Flanagan, "This is a tough job we're asking you to do." He added, "I don't know why I still hang on to the idea that unemployed actors get just as hungry as anybody else."

Hopkins promised a "free, adult, uncensored theatre." Flanagan worked for four years to make this happen. She wanted to build strong local and regional theatres across the United States. Her goal was to create a truly creative theatre in different parts of the country, based on their unique history and culture.

How It Worked

On October 24, 1935, Hallie Flanagan explained the main goals of the Federal Theatre Project:

- To reemploy theatre workers who were on public relief lists, including actors, directors, writers, designers, and stage technicians.

- To create theatres that were so important to their communities that they would continue even after the government program ended.

Within a year, the Federal Theatre Project employed 15,000 men and women. They earned about $23.86 a week, which was less than the Actors Equity Association's minimum of $40.00. These workers performed six shows a week and had four hours a day for rehearsals.

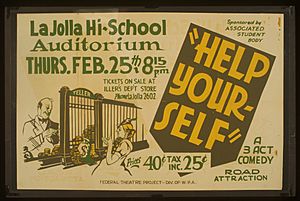

During its almost four years, 30 million people watched FTP shows. These shows were put on in over 200 theatres across the country. Many of these theatres had been closed but were reopened by the FTP. Shows also took place in parks, schools, churches, factories, and even closed-off streets. The project put on about 1,200 plays, not including its radio programs.

The Federal Theatre was created to give jobs and training, not to make money. So, when it started, there was no plan to collect money from tickets. By the end, 65 percent of its shows were still free. The total cost of the project was $46 million.

Flanagan explained that the money spent by the Federal Theatre was meant to pay wages to unemployed people. So, when people criticized the project for spending money, they were criticizing it for doing exactly what it was designed to do.

The FTP set up five main centers in New York City, Boston, Chicago, Los Angeles, and New Orleans. The project didn't operate in every state, especially those without many unemployed theatre workers. Some smaller projects in states like Alabama, Minnesota, and Iowa were closed over time.

Many famous artists of the time worked with the Federal Theatre Project. It also helped start the careers of a new generation of theatre artists. People like Arthur Miller, Orson Welles, John Houseman, and Elia Kazan became well-known partly because of their work with the FTP.

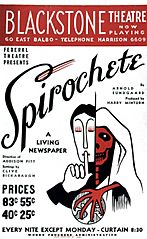

Living Newspaper Plays

Living Newspaper plays were a special type of show created by teams of researchers and writers. These teams would read newspaper articles about current events, like farm policies or housing problems. They would then turn these news stories into plays. The goal was to inform audiences, often with ideas that supported social change. For example, Triple-A Plowed Under criticized the U.S. Supreme Court for stopping a program that helped farmers.

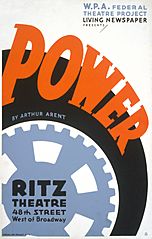

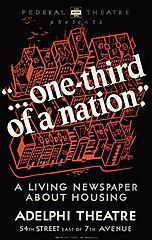

These plays, which openly discussed political issues, quickly caused problems with members of Congress. However, even with the controversy, Living Newspaper plays were very popular with audiences. They are perhaps the most famous type of work from the Federal Theatre Project.

Problems between the FTP and Congress grew when the State Department didn't like the first Living Newspaper play, Ethiopia. This play was about Haile Selassie and his country's fight against Italy. The U.S. government then ordered that the FTP, as a government agency, could not show foreign leaders on stage. This was to avoid diplomatic issues. Because of this, playwright and director Elmer Rice, who led the New York office of the FTP, quit in protest.

Examples of Living Newspaper Plays

These are some of the Living Newspaper plays. The numbers show how many other cities the play was performed in.

| Title | Author | City | Dates |

|---|---|---|---|

| Highlights of 1935 | Living Newspaper staff | New York | May 12–30, 1936 |

| Injunction Granted | Living Newspaper staff | New York | July 24–October 20, 1936 |

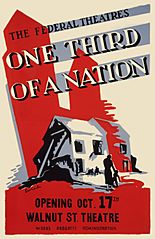

| One-Third of a Nation | Arthur Arent | New York + 9 | January 17–October 22, 1938 |

| Power | Arthur Arent | New York + 4 | February 23–July 10, 1937 |

| Triple-A Plowed Under | Living Newspaper staff | New York + 4 | March 14–May 2, 1936 |

African-American Theatre Units

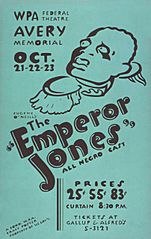

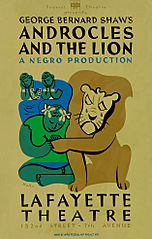

The Federal Theatre Project used its national network to celebrate the work of artists who hadn't been given many opportunities before. This included special groups like the French Theatre in Los Angeles, the German Theatre in New York City, and the Negro Theatre Unit. The Negro Theatre Unit had several branches across the country, with its largest office in New York City. In total, the FTP set up 17 Negro Theatre Units (NTU) in different cities. By the end of the project, 22 American cities had headquarters for Black theatre groups.

The New York Negro Theatre Unit was the most famous. Two of the four federal theatres in New York City, the Lafayette Theatre and the Negro Youth Theater, were dedicated to the Harlem community. Their goal was to help new, unknown theatre artists develop their skills.

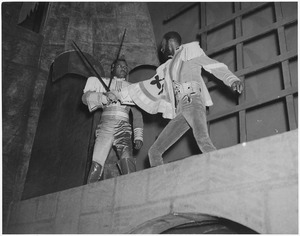

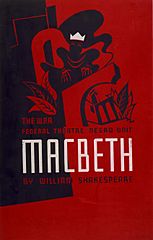

Both theatre projects were based at the Lafayette Theatre in Harlem. They put on about 30 plays there. One of the most popular was the Voodoo Macbeth (1936). This was Orson Welles's version of Shakespeare's play, set on a magical island that looked like the Haitian court of King Henri Christophe.

The New York Negro Theatre Unit also included the African American Dance Unit. This unit featured Nigerian artists who had been affected by the Ethiopian Crisis. These projects employed over 1,000 Black actors and directors. The Negro Actors' Guild of America was formed in 1936 to support the well-being and development of Black artists.

The Federal Theatre Project was special because it focused on fighting racial injustice. Hallie Flanagan told her staff to follow the WPA's policy against racial prejudice. For example, a white project manager in Dallas was fired for trying to separate Black and white theatre technicians. Also, a white assistant director was removed because he couldn't work well with Black artists.

The FTP actively worked with the African American community, including leaders like Carter G. Woodson and Walter Francis White of the NAACP. One rule for working in the FTP was having prior professional theatre experience. However, when 40 young, jobless Black playwrights needed work, Hallie Flanagan waived this rule. She wanted to give these new writers a chance to learn and share their stories.

This push for equality eventually became a problem for the Dies Committee in Congress. They stopped funding the Federal Theatre Project, claiming that "racial equality forms a vital part of the Communist dictatorship and practices."

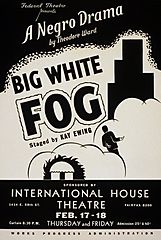

New Drama Productions

Here are some new drama productions. The numbers show how many other cities the play was performed in.

| Title | Author | City | Dates |

|---|---|---|---|

| Big White Fog | Theodore Ward | Chicago | April 7–May 30, 1938 |

| Conjur' Man Dies | Rudolph Fisher, adapted by Arna Bontemps and Countee Cullen | New York + 1 | March 11–July 4, 1936 |

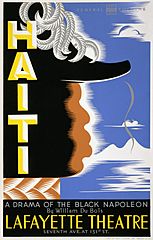

| Haiti | William DuBois | New York + 1 | March 2–November 5, 1938 |

| It Can't Happen Here | Sinclair Lewis, John C. Moffitt | Seattle + 20 | October 27–November 6, 1936 |

| Macbeth | William Shakespeare, adapted by Orson Welles | New York + 8 | April 14–October 17, 1936 |

| The Swing Mikado | adapted from Gilbert and Sullivan | Chicago + 3 | September 25, 1938 – February 25, 1939 |

| Walk Together Chillun | Frank H. Wilson | New York | February 4–March 7, 1936 |

Dance Drama Productions

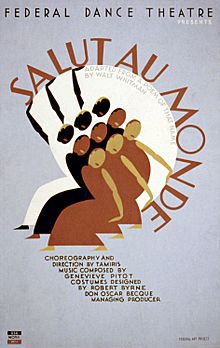

Dance drama combines dance and theatre to tell a story. Here are some new dance drama productions.

| Title | Author | City | Dates |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adelante | Helen Tamiris | New York | April 20–May 6, 1939 |

| An American Exodus | Myra Kinch | Los Angeles + 1 | July 27, 1937 – January 4, 1939 |

| How Long Brethren | Helen Tamiris | New York + 1 | May 6, 1937 – January 15, 1938 |

| Salut au Monde | Helen Tamiris | New York | July 23–August 5, 1936 |

Foreign-Language Plays

The Federal Theatre Project also put on plays in other languages, giving them their first professional performances in the United States.

German Plays

| Title | Author | City | Dates |

|---|---|---|---|

| Die Apostel | Rudolph Wittenberg | New York | April 15–20, 1936 |

Spanish Plays

| Title | Author | City | Dates |

|---|---|---|---|

| Esto No Pasará Aqui | Sinclair Lewis, John C. Moffitt | Tampa | October 27–November 1, 1936 |

Yiddish Plays

| Title | Author | City | Dates |

|---|---|---|---|

| Awake and Sing | Clifford Odets, adapted by Chaver Paver | New York + 1 | December 22, 1938 – April 9, 1939 |

| It Can't Happen Here | Sinclair Lewis, John C. Moffitt | Los Angeles New York Paterson, N. J. |

October 27–November 3, 1936 October 27, 1936 – May 1, 1937 April 18–19, 1937 |

Radio Programs

The Federal Theatre of the Air started weekly radio broadcasts on March 15, 1936. For three years, the radio part of the project produced about 3,000 programs each year. These shows were broadcast on commercial stations and major networks like NBC, Mutual, and CBS. Most of the main programs came from New York, but radio divisions were also set up in 11 other states.

The radio shows covered many topics, including health, safety, art, music, and history. There were children's programs like Once Upon a Time and shows about science. In 1939, Hallie Flanagan even broadcast the story of the Federal Theatre Project to Britain.

Why Congress Stopped Funding

In May 1938, Martin Dies Jr., who led The House Committee on Un-American Activities, specifically looked into the Federal Theatre Project. The committee heard from former FTP members who were unhappy with their time there. They questioned Hallie Flanagan's leadership and political beliefs. Flanagan argued that the FTP was pro-American because it celebrated freedom of speech and expression to talk about important issues.

Congress decided to stop funding the Federal Theatre Project on June 30, 1939. They claimed that the project promoted racial equality and was involved in "radical and communist activities." This decision immediately put 8,000 people out of work across the country. Even though the FTP cost very little compared to the WPA's total budget, Congress felt that most Americans didn't think theatre was a good use of their tax money. After the decision, someone in Congress was quoted saying, "Culture! What the Hell—Let 'em have a pick and shovel!"

Members of Congress criticized 81 of the Federal Theatre Project's 830 main plays. Only 29 of these were original plays created by the FTP. The others were older plays, community productions, or plays that were never even performed by the project.

The Living Newspaper plays that caused problems included Injunction Granted, which was about American labor history; One-Third of a Nation, about housing problems in New York; Power, about energy from the consumer's point of view; and Triple A Plowed Under, about farming issues.

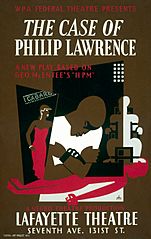

Plays from the Negro Theatre Unit that were criticized included The Case of Philip Lawrence, which showed life in Harlem; Did Adam Sin?, a musical review of Black folklore; and Haiti, a play about Toussaint Louverture.

Even some children's plays were criticized, like Mother Goose Goes to Town and Revolt of the Beavers. The musical Sing for Your Supper also faced criticism, even though its patriotic song, "Ballad for Americans", became famous and was used by the Republican National Convention in 1940.

See also

In Spanish: Proyecto de Teatro Federal para niños

In Spanish: Proyecto de Teatro Federal para niños

| Dorothy Vaughan |

| Charles Henry Turner |

| Hildrus Poindexter |

| Henry Cecil McBay |