Elia Kazan facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Elia Kazan

|

|

|---|---|

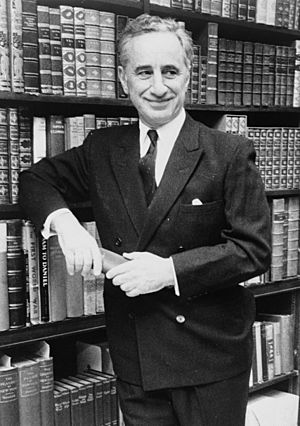

Kazan c. 1950

|

|

| Born |

Elias Kazantzoglou

September 7, 1909 |

| Died | September 28, 2003 (aged 94) New York City, U.S.

|

| Education | Williams College (BA) Yale University |

| Occupation |

|

| Years active | 1934–1976 |

| Spouse(s) |

|

| Children | 5, including Nicholas |

| Relatives |

|

| Signature | |

Elia Kazan (born Elias Kazantzoglou; September 7, 1909 – September 28, 2003) was a famous American film and theater director, producer, writer, and actor. The New York Times called him "one of the most honored and influential directors" in the history of Broadway and Hollywood.

Kazan was born in Constantinople (now Istanbul, Turkey) to Greek parents. His family moved to the United States in 1913. After studying at Williams College and the Yale School of Drama, he worked as an actor for eight years. In 1932, he joined the Group Theatre, and in 1947, he helped start the Actors Studio. This studio, along with Robert Lewis and Cheryl Crawford, taught a style of acting called "Method Acting" under Lee Strasberg. Kazan also acted in a few movies, like City for Conquest (1940).

His films often explored important personal or social topics. Kazan once said he only made films about subjects he deeply cared about. His first film like this was Gentleman's Agreement (1947), starring Gregory Peck, which was about antisemitism (prejudice against Jewish people) in America. This movie was nominated for eight Oscars and won three, including Kazan's first for Best Director. He then directed Pinky (1949), which was one of the first Hollywood films to deal with racism against African Americans.

A Streetcar Named Desire (1951), which he had also directed as a play, received twelve Oscar nominations and won four. It was a breakthrough role for Marlon Brando. Three years later, Kazan directed Brando again in On the Waterfront, a movie about corruption in the New York harbor unions. This film also received 12 Oscar nominations and won eight. In 1955, he directed John Steinbeck's East of Eden, which introduced James Dean to movie audiences.

A big moment in Kazan's career happened in 1952 when he testified before the House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC). This committee was investigating people suspected of being Communists during the Hollywood blacklist era. His testimony caused strong negative reactions from many friends and colleagues. When Kazan received an honorary Oscar in 1999, some actors chose not to applaud, and demonstrators protested the event.

Kazan's films in the 1950s and 1960s were known for their thought-provoking, issue-based stories. Director Stanley Kubrick called him "the best director we have in America." In 2010, Martin Scorsese co-directed a documentary called A Letter to Elia as a personal tribute to Kazan.

Contents

Early Life and Family

Elia Kazan was born in the Kadıköy area of Constantinople (now Istanbul). His parents were Cappadocian Greeks from Kayseri in Anatolia. He came to the United States with his parents, George and Athena Kazantzoglou, on July 8, 1913. He was named after his grandfather, Elia Kazantzoglou. His brother, Avraam, was born in Berlin and later became a psychiatrist.

Kazan grew up in the Greek Orthodox Church. As a young boy, he was shy and his college friends described him as a loner. Much of his early life is shown in his book, America America, which he later made into a film in 1963. In the book, he wrote that his family felt "alienated" from both their Greek Orthodox traditions and from American society. His mother's family were cotton merchants. His father became a rug merchant after moving to the U.S. and wanted Elia to join the family business.

After high school, Kazan went to Williams College in Massachusetts. He paid for his studies by waiting tables and washing dishes, and he graduated with honors. He also worked as a bartender but never joined a fraternity. At Williams, he got the nickname "Gadg" (short for Gadget) because he was "small, compact, and handy." This nickname was later used by his movie stars.

In America America, Kazan explains why his family left Turkey for America. He said much of the story came from tales he heard as a child. He mentioned that his uncle, still a boy, took the family's wealth on a donkey to Istanbul to help the family escape difficult times. He also said his uncle lost the money and ended up sweeping rugs in a small store.

Before making the film, Kazan wanted to check the details of his family's past. He recorded his parents answering his questions. He asked his father, "Why America? What were you hoping for?" His mother answered, "A.E. brought us here." A.E. was his uncle Avraam Elia, who traveled from their village with the donkey. At 28, he somehow made it to New York, sent money home, and eventually brought Kazan's father over. His father then sent for Kazan's mother, baby brother, and him when he was four.

Kazan called America America his favorite film because it was "entirely mine."

Becoming a Director

In 1932, after two years at the Yale University School of Drama, Kazan moved to New York City to become a professional stage actor. He also studied singing at the Juilliard School. His first chance came with a small group of actors called the Group Theatre. They performed plays that commented on society. Kazan found a strong sense of belonging within this group and in the social movements of that time.

In his autobiography, Kazan wrote about the "lasting impact" the Group had on him. He saw Lee Strasberg and Harold Clurman as "father figures" and became close friends with playwright Clifford Odets.

Kazan first became successful as a theater director in New York. Even though he was told early on that he wasn't a good actor, he surprised many by becoming one of the Group's best. In 1935, he played a taxi driver leading a strike in Clifford Odets' play, Waiting for Lefty. His performance was called "dynamic."

A common theme in all his work was "personal alienation and anger over social injustice." Other critics noted his strong focus on the social meaning of plays.

By the mid-1930s, when he was 26, he started directing many of the Group Theatre's plays, including Robert Ardrey's Thunder Rock. In 1942, he had a big success directing Thornton Wilder's play, The Skin of Our Teeth, starring Tallulah Bankhead and Fredric March. The play was a hit and won Wilder a Pulitzer Prize. Kazan won the New York Drama Critics Award for Best Director. Kazan then directed Death of a Salesman by Arthur Miller and A Streetcar Named Desire by Tennessee Williams, both of which were very successful. Kazan's wife, Molly Thacher, helped discover Williams and gave him an award that started his career.

The Group Theatre often rehearsed in the summer at Pine Brook Country Club in Nichols, Connecticut. Many other artists were there, including Harry Morgan, John Garfield, Luise Rainer, Frances Farmer, Will Geer, Howard da Silva, Clifford Odets, Lee J. Cobb, and Irwin Shaw.

The Actors Studio and Early Films

In 1940, Kazan had a big supporting role as a gangster in the boxing movie City for Conquest, starring James Cagney. His unique and stylish clothing in the film seemed to influence Frank Sinatra years later.

In 1947, Kazan started the Actors Studio, a non-profit workshop, with actors Robert Lewis and Cheryl Crawford. In 1951, Lee Strasberg became its director after Kazan moved to Hollywood to focus on directing movies. Strasberg introduced the "Method" to the Actors Studio. This "Method" became the main acting style in Hollywood after World War II.

Some of Strasberg's students included Montgomery Clift, Mildred Dunnock, Julie Harris, Karl Malden, Patricia Neal, Maureen Stapleton, Eli Wallach, and James Whitmore. Kazan directed two of the Studio's talents, Karl Malden and Marlon Brando, in the play A Streetcar Named Desire.

Even though he was very successful in theater, Kazan decided to direct movies in Hollywood. After directing two short films, his first feature film was A Tree Grows in Brooklyn (1945). This was one of his first attempts to make dramas about current social issues, which became his specialty. Two years later, he directed Gentleman's Agreement, where he dealt with antisemitism, a topic rarely discussed in America. For this film, he won his first Oscar for Best Director. In 1947, he directed the courtroom drama Boomerang!. In 1949, he directed Pinky, which explored racism in America and was nominated for three Academy Awards.

Rise to Prominence in the 1950s

In 1950, Kazan directed Panic in the Streets, a thriller starring Richard Widmark filmed on the streets of New Orleans. In this movie, Kazan tried a documentary-like style of filming, which made the action scenes more exciting. He won the Venice Film Festival International Award for directing, and the film also won two Academy Awards. Kazan even asked for Zero Mostel to act in the film, even though Mostel was "blacklisted" due to earlier HUAC testimony.

In 1951, after introducing and directing Marlon Brando and Karl Malden in the play version, he cast them both in the movie A Streetcar Named Desire. This film won four Oscars and was nominated for 12.

Kazan's next film was Viva Zapata! (1952), also starring Marlon Brando. This movie felt very real because it was filmed in actual locations and the actors used strong character accents. Kazan called this his "first real film" because of these elements.

In 1954, he directed Brando again in On the Waterfront. Continuing his focus on social issues, this film showed corruption within New York's longshoremen's union. It was nominated for 12 Academy Awards and won 8, including Best Picture, Best Director, and Best Actor for Marlon Brando.

On the Waterfront was also the first movie for Eva Marie Saint, who won an Oscar for Best Supporting Actress. Saint remembered that Kazan chose her after she did an acting exercise with Brando. Life magazine called On the Waterfront the "most brutal movie of the year" but also with "the year's tenderest love scenes."

The film used many real street and waterfront scenes and had a great musical score by Leonard Bernstein.

After On the Waterfront, Kazan directed another movie based on a John Steinbeck novel, East of Eden (1955). As director, Kazan again used an unknown actor, James Dean. Kazan had seen Dean on stage in New York and gave him the main role. Dean flew to Los Angeles with Kazan in 1954, bringing his clothes in a paper bag. The film's success made James Dean a popular actor. He went on to star in Rebel Without a Cause (1955) and Giant (1956).

Author Douglas Rathgeb described how difficult it was for Kazan to turn Dean into a new star. There were rumors that Dean "kept a loaded gun in his studio trailer" and "drove his motorcycle dangerously." Kazan had to "baby-sit the young actor" to make sure he didn't run away. Co-star Julie Harris worked hard to calm Dean's panic attacks. Dean often didn't understand Hollywood's ways.

Dean was amazed when he saw a rough cut of the film. Kazan invited director Nicholas Ray to a private showing with Dean. Ray watched Dean's powerful acting on screen, but it seemed impossible that it was the same shy person in the room. The film also used outdoor scenes and early widescreen format well, making it one of Kazan's best works. James Dean died the next year at age 24 in a car accident. He had only made three films, and East of Eden was the only one he saw completed.

Continued Work in the 1960s

In 1961, Kazan introduced Warren Beatty in his first movie role, starring in Splendor in the Grass (1961) with Natalie Wood. The film was nominated for two Oscars and won one.

Natalie Wood was at a point in her career where she wanted to move from child roles to adult ones. Kazan cast her as the lead in Splendor in the Grass, and her career took off again.

Actor Gary Lockwood, who was also in the film, felt that "Kazan and Natalie were a terrific marriage" because he could get amazing performances from her. Kazan's favorite scene was the last one, when Wood goes back to see her first love, Bud (Beatty). Kazan said, "It's terribly touching to me. I still like it when I see it. And I certainly didn't need to tell her how to play it. She understood it perfectly."

His Directing Style

Kazan aimed for "cinematic realism," meaning he wanted his films to feel very real. He often achieved this by finding and working with unknown actors. Many of these actors saw him as a mentor. He believed that casting the right actors was 90% of a movie's success. Because of his efforts, he gave actors like Lee Remick, Jo Van Fleet, Warren Beatty, Andy Griffith, James Dean, and Jack Palance their first big movie roles. He explained that "big stars are barely trained or not very well trained. They also have bad habits... they're not pliable anymore."

Kazan described how he understood James Dean:

When I met him he said, "I'll take you for a ride on my motorbike..." It was his way of communicating with me, saying "I hope you like me..." I thought he was an extreme grotesque of a boy, a twisted boy. As I got to know his father, as I got to know about his family, I learned that he had been, in fact, twisted by the denial of love ... I went to Jack Warner and told him I wanted to use an absolutely unknown boy. Jack was a crapshooter of the first order, and said, "Go ahead."

Kazan chose subjects for his films that reflected personal and social events he knew well. Film historian Joanna E. Rapf noted that Kazan focused on "reality" in his work with actors. She added, "He respects his script, but casts and directs with a particular eye for expressive action and the use of emblematic objects." Kazan said that "unless the character is somewhere in the actor himself, you shouldn't cast him."

Film author Peter Biskind described Kazan's career as "fully committed to art and politics, with the politics feeding the work." Some of his films had clear political messages. In 1954, he directed On the Waterfront, which was about union corruption. Many critics consider it "one of the greatest films." Another political film was A Face in the Crowd (1957). The main character, played by Andy Griffith, becomes deeply involved in politics. Kazan and writer Budd Schulberg used the film to warn audiences about the power of television. Kazan explained they were trying to warn "of the power TV would have in the political life of the nation." He advised, "Listen to what the candidate says; don't be taken in by his charm... Don't buy the advertisement; buy what's in the package."

As a product of the Group Theatre and Actors Studio, Kazan was known for using "Method" actors, especially Brando and Dean. In a 1988 interview, Kazan said, "I did whatever was necessary to get a good performance including so-called Method acting. I made them run around the set, I scolded them, I inspired jealousy in their girlfriends... The director is a desperate beast!... You don't deal with actors as dolls. You deal with them as people who are poets to a certain degree." Actor Robert De Niro called him a "master of a new kind of psychological and behavioral faith in acting."

Kazan had strong ideas about scenes and tried to combine an actor's suggestions and feelings with his own.

Joanna Rapf added that Kazan was most admired for his close work with actors. Director Nicholas Ray called him "the best actor's director the United States has ever produced." Film historian Foster Hirsch explained that "he created virtually a new acting style, which was the style of the Method... [that] allowed for the actors to create great depth of psychological realism."

Many actors said Kazan greatly influenced their careers. Patricia Neal, who starred with Andy Griffith in A Face in the Crowd (1957), said: "He was very good. He was an actor and he knew how we acted. He would come and talk to you privately. I liked him a lot."

To get great acting from Andy Griffith in his first movie, Kazan sometimes took surprising steps. For one important emotional scene, Kazan warned Griffith: "I may have to use extraordinary means to make you do this. I may have to get out of line. I don't know any other way of getting an extraordinary performance out of an actor."

Actress Terry Moore called Kazan her "best friend." She said, "he made you feel better than you thought you could be. I never had another director that ever touched him. I was spoiled for life." Carroll Baker, star of Baby Doll, said, "He would find out if your life was like the character; he was the best director with actors."

Kazan's close work with actors continued until his last film, The Last Tycoon (1976). He remembered that Robert De Niro, the star, "would do almost anything to succeed." De Niro even lost a lot of weight for the role. Kazan added that De Niro "is one of a select number of actors I've directed who work hard at their trade, and the only one who asked to rehearse on Sundays." Kazan used De Niro's personality traits for his character in the film. Even though the movie didn't do well at the box office, some critics praised De Niro's acting.

The HUAC Controversy

Kazan testified before the House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC) in 1952. In his mid-20s, during the Great Depression (1934 to 1936), he had been a member of the American Communist Party in New York for about a year and a half.

In April 1952, the Committee asked Kazan, under oath, to identify Communists from that time, 16 years earlier. Kazan first refused to give names, but he eventually named eight former Group Theatre members he said had been Communists. These included Clifford Odets, Morris Carnovsky, and Art Smith. He said that Odets left the party at the same time he did. Kazan claimed all the people he named were already known to HUAC, but this has been debated. Kazan later wrote about how his naming of Art Smith hurt the actor's career. Naming names cost Kazan many friends in the film industry, including playwright Arthur Miller, though they did work together again.

Kazan later wrote in his autobiography about the "warrior pleasure at withstanding his enemies." When Kazan received an Honorary Academy Award in 1999, the audience was divided. Some, like Nick Nolte, Ed Harris, and Amy Madigan, refused to applaud. Others, like Kathy Bates, Meryl Streep, Karl Malden, and Warren Beatty, stood and applauded.

In 1982, Orson Welles was asked about Kazan. Welles replied that Elia Kazan was a "traitor" who "sold to McCarthy all his companions" while he could still work. Welles added that Kazan then made On the Waterfront, which was "a celebration of the informer."

Los Angeles Times film critic Kenneth Turan wrote that "The only criterion for an award like this is the work." Kazan had already been "denied accolades" from other film groups. Joseph McBride, a former vice president of the Los Angeles Film Critics Association, argued that an honorary award recognizes "the totality of what he represents, and Kazan's career, post 1952, was built on the ruin of other people's careers."

Arthur Miller, a friend of Kazan, once told him, "Don't worry about what I'll think. Whatever you do is okay with me, because I know that your heart is in the right place."

In his memoirs, Kazan wrote that his testimony meant "the big shot had become the outsider." He also noted that it strengthened his friendship with Tennessee Williams, with whom he worked on many plays and films. He called Williams "the most loyal and understanding friend I had through those black months."

Kazan appears as a character in Names, a play by Mark Kemble about former Group Theatre members and their struggles with the House Un-American Activities Committee.

Personal Life and Death

Kazan was married three times. His first wife was playwright Molly Day Thacher. They were married from 1932 until her death in 1963 and had two daughters and two sons, including screenwriter Nicholas Kazan. His second marriage was to actress Barbara Loden, from 1967 until her death in 1980, and they had one son. His third marriage, in 1982, was to Frances Rudge, and it lasted until his death in 2003.

In the early 1930s, Kazan and his first wife moved to an old farmhouse in Sandy Hook, Connecticut, where they raised their four children. They used this home as a summer and weekend getaway until 1998.

In 1978, the U.S. government paid for Kazan and his family to visit his birthplace, where many of his films were shown. In a speech in Athens, he talked about his films, his life in the U.S., and the messages he tried to share.

Elia Kazan died from natural causes in his Manhattan apartment on September 28, 2003, at the age of 94.

His Legacy

Kazan was known as an "actor's director" because he helped many of his stars give some of their best performances. Under his direction, his actors received 24 Academy Award nominations and won nine Oscars.

He won the Best Director for Gentleman's Agreement (1947) and for On the Waterfront (1954). Both A Streetcar Named Desire (1951) and On the Waterfront were nominated for twelve Academy Awards each, winning four and eight respectively.

With his many years at the Group Theatre and Actors Studio in New York City, and later his successes on Broadway, he became famous "for the power and intensity of his actors' performances." He played a key role in starting the film careers of Marlon Brando, James Dean, Julie Harris, Eli Wallach, Eva Marie Saint, Warren Beatty, Lee Remick, Karl Malden, and many others. Seven of Kazan's films won a total of 20 Academy Awards. Dustin Hoffman said he "doubted whether he, Robert De Niro, or Al Pacino, would have become actors without Mr. Kazan's influence."

When he died at 94, The New York Times called him "one of the most honored and influential directors in Broadway and Hollywood history." Death of a Salesman and A Streetcar Named Desire, two plays he directed, are considered some of the greatest of the 20th century. He successfully moved from being a respected Broadway director to one of the most important film directors of his time. Critic William Baer noted that throughout his career, "he constantly rose to the challenge of his own aspirations," adding that "he was a pioneer and visionary who greatly affected the history of both stage and cinema." Some of his film materials and personal papers are kept at the Wesleyan University Cinema Archives, where scholars can access them.

His testimony before the House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC) in 1952 was a low point in his career. However, he always believed he made the right decision to give the names of Communist Party members. In a 1976 interview, he said, "I would rather do what I did than crawl in front of a ritualistic Left and lie the way those other comrades did, and betray my own soul. I didn't betray it. I made a difficult decision."

During his career, Kazan won both Tony and Oscar Awards for directing on stage and screen. In 1982, President Ronald Reagan gave him the Kennedy Center Honors award, a national tribute for lifetime achievement in the arts. At the ceremony, screenwriter Budd Schulberg, who wrote On the Waterfront, thanked his friend, saying, "Elia Kazan has touched us all with his capacity to honor not only the heroic man, but the hero in every man."

In 1999, at the 71st Academy Awards, Martin Scorsese and Robert De Niro presented the Honorary Oscar to Kazan. Because of Kazan's past with the Hollywood Blacklist in the 1950s, some audience members, including Nick Nolte and Ed Harris, refused to applaud. Others, like Warren Beatty, Meryl Streep, Kathy Bates, and Kurt Russell, gave him a standing ovation.

Martin Scorsese directed a documentary film, A Letter to Elia (2010), which is a very personal tribute to Kazan. Scorsese was "captivated" by Kazan's films when he was young and credits Kazan as his inspiration for becoming a filmmaker. It won a Peabody Award in 2010.

Filmography

| Year | Film | Distributor |

|---|---|---|

| 1945 | A Tree Grows in Brooklyn | 20th Century Fox |

| 1947 | The Sea of Grass | Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer |

| Boomerang! | 20th Century Fox | |

| Gentleman's Agreement | ||

| 1949 | Pinky | |

| 1950 | Panic in the Streets | |

| 1951 | A Streetcar Named Desire | Warner Bros. |

| 1952 | Viva Zapata! | 20th Century Fox |

| 1953 | Man on a Tightrope | |

| 1954 | On the Waterfront | Columbia Pictures |

| 1955 | East of Eden | Warner Bros. |

| 1956 | Baby Doll | |

| 1957 | A Face in the Crowd | |

| 1960 | Wild River | 20th Century Fox |

| 1961 | Splendor in the Grass | Warner Bros. |

| 1963 | America America | |

| 1969 | The Arrangement | Warner Bros.-Seven Arts |

| 1972 | The Visitors | United Artists |

| 1976 | The Last Tycoon | Paramount Pictures |

Documentary

- People of the Cumberland (1937)

- Watchtower Over Tomorrow (1945)

As an actor

- City for Conquest (1940)

- Blues in the Night (1941)

Awards and Nominations

| Year | Award | Category | Title | Results | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1947 | Academy Awards | Best Director | Gentleman's Agreement | Won | |

| 1951 | A Streetcar Named Desire | Nominated | |||

| 1954 | On the Waterfront | Won | |||

| 1955 | East of Eden | Nominated | |||

| 1963 | Best Picture | America America | Nominated | ||

| Best Director | Nominated | ||||

| Best Adapted Screenplay | Nominated | ||||

| 1998 | Academy Honorary Award | Lifetime Achievement | Won | ||

| 1947 | Tony Awards | Best Direction | All My Sons | Won | |

| 1949 | Death of a Salesman | Won | |||

| 1956 | Cat on a Hot Tin Roof | Nominated | |||

| 1958 | Best Play | The Dark at the Top of the Stairs | Nominated | ||

| Best Direction of a Play | Nominated | ||||

| 1959 | J.B. | Won | |||

| 1960 | Sweet Bird of Youth | Nominated | |||

| 1948 | Golden Globe Awards | Best Motion Picture Director | Gentleman's Agreement | Won | |

| 1954 | On The Waterfront | Won | |||

| 1956 | Baby Doll | Won | |||

| 1963 | America America | Won | |||

| 1952 | British Academy Film Awards | Best Film | A Streetcar Named Desire | Nominated | |

| Viva Zapata! | Nominated | ||||

| 1954 | On the Waterfront | Nominated | |||

| 1955 | East of Eden | Nominated | |||

| 1956 | Baby Doll | Nominated | |||

| 1952 | Cannes Film Festival | Grand Prize of the Festival | Viva Zapata! | Nominated | |

| 1955 | Best Dramatic Film | East of Eden | Won | ||

| Palme d'Or | Nominated | ||||

| 1972 | The Visitors | Nominated | |||

| 1953 | Berlin Film Festival | Golden Bear | Man on a Tightrope | Nominated | |

| 1960 | Wild River | Nominated | |||

| 1996 | Honorary Golden Bear | N/A | Won | ||

| 1948 | Venice Film Festival | International Award | Gentleman's Agreement | Nominated | |

| 1950 | Panic in the Streets | Nominated | |||

| 1950 | Golden Lion | Won | |||

| 1951 | A Streetcar Named Desire | Nominated | |||

| 1951 | Special Jury Prize | Won | |||

| 1954 | Golden Lion | On the Waterfront | Nominated | ||

| 1954 | Silver Lion | Won | |||

| 1955 | OCIC Award | Won |

In addition to these awards, Kazan has a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, located on 6800 Hollywood Boulevard. He is also a member of the American Theater Hall of Fame.

Directed Academy Award Performances

| Year | Performer | Film | Winner |

|---|---|---|---|

| Academy Award for Best Actor | |||

| 1947 | Gregory Peck | Gentleman's Agreement | Nominated |

| 1951 | Marlon Brando | A Streetcar Named Desire | Nominated |

| 1952 | Viva Zapata! | Nominated | |

| 1954 | On the Waterfront | Won | |

| 1955 | James Dean | East of Eden | Nominated |

| Academy Award for Best Actress | |||

| 1947 | Dorothy McGuire | Gentleman's Agreement | Nominated |

| 1949 | Jeanne Crain | Pinky | Nominated |

| 1951 | Vivien Leigh | A Streetcar Named Desire | Won |

| 1956 | Carroll Baker | Baby Doll | Nominated |

| 1961 | Natalie Wood | Splendor in the Grass | Nominated |

| Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor | |||

| 1945 | James Dunn | A Tree Grows in Brooklyn | Won |

| 1951 | Karl Malden | A Streetcar Named Desire | Won |

| 1952 | Anthony Quinn | Viva Zapata! | Won |

| 1954 | Lee J. Cobb | On the Waterfront | Nominated |

| Karl Malden | Nominated | ||

| Rod Steiger | Nominated | ||

| Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress | |||

| 1947 | Celeste Holm | Gentleman's Agreement | Won |

| Anne Revere | Nominated | ||

| 1949 | Ethel Barrymore | Pinky | Nominated |

| Ethel Waters | Nominated | ||

| 1951 | Kim Hunter | A Streetcar Named Desire | Won |

| 1954 | Eva Marie Saint | On the Waterfront | Won |

| 1955 | Jo Van Fleet | East of Eden | Won |

| 1956 | Mildred Dunnock | Baby Doll | Nominated |

See also

In Spanish: Elia Kazan para niños

In Spanish: Elia Kazan para niños