Montgomery Clift facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Montgomery Clift

|

|

|---|---|

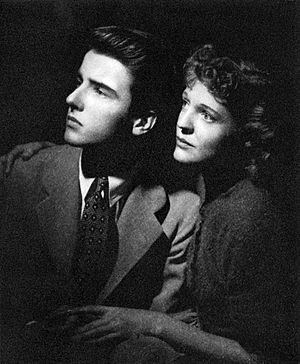

Studio publicity photograph, c. 1948

|

|

| Born |

Edward Montgomery Clift

October 17, 1920 Omaha, Nebraska, U.S.

|

| Died | July 23, 1966 (aged 45) New York City, U.S.

|

| Other names | Monty Clift |

| Occupation | Actor |

| Years active | 1935–1966 |

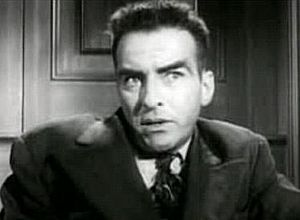

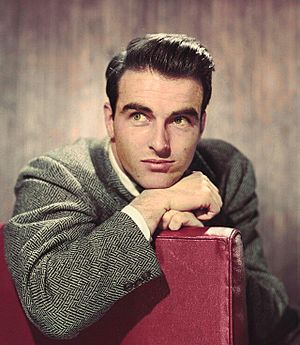

Edward Montgomery Clift (born October 17, 1920 – died July 23, 1966) was a famous American actor. He was nominated four times for an Academy Award. People knew him for playing "moody, sensitive young men."

He is best remembered for his roles in several important films. These include Red River (1948), A Place in the Sun (1951), and From Here to Eternity (1953). He also starred in Judgment at Nuremberg (1961) and The Misfits (1961).

Montgomery Clift was one of the first actors to use a style called "method acting." This is where actors try to really feel and understand their characters. He was invited to study at the Actors Studio with famous teachers Lee Strasberg and Elia Kazan. When he first came to Hollywood, he made a rare choice. He did not sign a long-term contract until his first two movies were successful. This gave him more control over his career.

Contents

Early Life and Acting Start

Edward Montgomery Clift was born on October 17, 1920, in Omaha, Nebraska. His father, William Brooks Clift, was a company vice-president. His mother was Ethel Fogg Clift. His parents were Quakers and met at Cornell University. Montgomery had a twin sister, Roberta, and an older brother, William Jr.

His mother wanted her children to have a special upbringing. So, Montgomery and his siblings were taught at home. They traveled a lot in America and Europe. They learned to speak German and French fluently. When he was seven, Montgomery had an injury to his neck while swimming. This left him with a scar.

The Wall Street Crash of 1929 and the Great Depression made his father lose money. His family had to move and live a simpler life. Montgomery once joked that his childhood was "hobgoblin" because his parents traveled so much.

Starting on Stage: 1934–1946

Montgomery Clift became interested in acting as a child. He lived in Switzerland and France for a time. When he was 13, his family moved to Florida. He got a small, unpaid role in a local play.

About a year later, his family moved to New York City. At 14, Montgomery made his first appearance on Broadway. He was in the play Fly Away Home. Critics noticed his "amazing poise." He continued to act on stage and worked with many famous actors.

In 1939, he was part of one of the first television broadcasts in the United States. His play Hay Fever was shown on TV during the 1939 New York World's Fair. At age 20, he was in There Shall Be No Night, which won a special award in 1941.

Clift also performed on radio early in his career. He was in radio plays like Ah, Wilderness! and The Glass Menagerie. He did not serve in World War II due to health reasons.

Becoming a Film Star

Rising to Fame: 1946–1956

At 25, Montgomery Clift got his first Hollywood movie role. It was in the Western film Red River (1948). The director, Howard Hawks, was very impressed with his stage acting. The movie was a big success and was nominated for two Academy Awards.

His second film, The Search, came out the same year. This movie earned him his first nomination for Best Actor. People were amazed by his natural acting. He even helped rewrite parts of the script.

Many Hollywood studios wanted to sign Clift. He chose a special deal with Paramount Pictures. It was a three-film deal, not the usual seven-year contract. This gave him the freedom to say no to scripts and directors. This was very unusual for a young actor. By the end of 1948, he was on the cover of Life magazine.

Clift's next film was The Heiress (1949). He worked very hard on his roles. He often rehearsed intensely with his acting coach. He then filmed The Big Lift (1950) in Berlin.

His role as George Eastman in A Place in the Sun (1951) is one of his most famous. He prepared deeply for the character. He even spent a night in a real prison for his jail scenes. He was nominated for another Best Actor for this film. The movie was highly praised. There were also rumors that he and co-star Elizabeth Taylor were dating.

After a break, Clift made three more films that came out in 1953. These were I Confess, Terminal Station, and From Here to Eternity. For From Here to Eternity, he trained hard. He learned to play the bugle for his role as a soldier. This film earned him his third Academy Award nomination.

Car Accident and Later Career

On May 12, 1956, while filming Raintree County, Clift was in a serious car accident. He was leaving a dinner party at Elizabeth Taylor's house. His car crashed into a telephone pole. Elizabeth Taylor found him and helped him before the ambulance arrived.

He suffered many injuries to his face, including a broken jaw and nose. He needed plastic surgery. After two months, he returned to finish the film. His face looked different after the accident, especially the left side. He faced ongoing health challenges and pain after the accident.

Later Films: 1957–1966

After his accident, Montgomery Clift continued to make many films. His next movies included The Young Lions (1958), where he acted with Marlon Brando. He also starred in Lonelyhearts (1958), Suddenly, Last Summer (1959), and Wild River (1960).

In The Misfits (1961) and Judgment at Nuremberg (1961), he took on smaller, but very powerful, roles. In The Misfits, he played a rodeo rider. In Judgment at Nuremberg, he played a German baker with a developmental disability. His performance in Judgment at Nuremberg earned him his fourth Academy Award nomination. The director, Stanley Kramer, praised his acting.

After filming Freud: The Secret Passion (1962), he faced some legal issues with the studio. They said he caused delays. He said there were too many last-minute script changes. The case was settled, but it affected his reputation. He found it hard to get film roles for four years.

In 1963, Clift appeared on a live TV show called The Hy Gardner Show. He talked about his films and his car accident for the first time publicly. He also did voice work during this time. He recorded a radio play of The Glass Menagerie and narrated a documentary.

Elizabeth Taylor helped him get a role in the film Reflections in a Golden Eye. To prepare, he took a role in a French thriller called The Defector (1966). He insisted on doing his own stunts, even swimming in a cold river. He was supposed to start Reflections in a Golden Eye in August 1966, but he passed away in July.

Death

On July 22, 1966, Montgomery Clift was at his home in New York City. His private nurse found him dead the next morning, July 23, 1966.

An examination showed that he died from a heart attack. He was 45 years old. His funeral was held at St. James' Church in Manhattan. About 150 guests attended, including famous actors like Lauren Bacall and Frank Sinatra. He was buried in the Friends Quaker Cemetery in Brooklyn. Elizabeth Taylor sent flowers from Rome.

Filmography

Film

| Year | Title | Role | Director | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1948 | The Search | Ralph "Steve" Stevenson | Fred Zinnemann | |

| Red River | Matthew "Matt" Garth | Howard Hawks | ||

| 1949 | The Heiress | Morris Townsend | William Wyler | |

| 1950 | The Big Lift | Danny MacCullough | George Seaton | |

| 1951 | A Place in the Sun | George Eastman | George Stevens | |

| 1953 | I Confess | Fr. Michael William Logan | Alfred Hitchcock | |

| Terminal Station (re-edited and rereleased in the United States as Indiscretion of an American Wife) |

Giovanni Doria | Vittorio De Sica | ||

| From Here to Eternity | Robert E. Lee "Prew" Prewitt | Fred Zinnemann | ||

| 1957 | Raintree County | John Wickliff Shawnessy | Edward Dmytryk | |

| 1958 | The Young Lions | Noah Ackerman | Edward Dmytryk | |

| Lonelyhearts | Adam White | Vincent J. Donehue | ||

| 1959 | Suddenly, Last Summer | Dr. John Cukrowicz | Joseph L. Mankiewicz | |

| 1960 | Wild River | Chuck Glover | Elia Kazan | |

| 1961 | The Misfits | Perce Howland | John Huston | |

| Judgment at Nuremberg | Rudolph Petersen | Stanley Kramer | ||

| 1962 | Freud: The Secret Passion | Sigmund Freud | John Huston | |

| 1966 | The Defector | Prof. James Bower | Raoul Lévy | Posthumous release |

Television

| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1939 | Hay Fever | Performer | Television Movie |

| 1963 | What's My Line? | Mystery Guest | Episode: Montgomery Clift |

| 1963 | The Merv Griffin Show | Self | Season 1 - Episode: 86 |

| 1965 | William Faulkner's Mississippi | Narrator | Television Documentary |

Theatre

| Year | Title | Role | Venue |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1933 | As Husbands Go | Performer | Sarasota, Florida |

| 1935 | Fly Away Home | Harmer Masters | 48th Street Theatre, Broadway |

| 1935 | Jubilee | Prince Peter | Imperial Theatre, Broadway |

| 1938 | Yr. Obedient Husband | Lord Finch | Broadhurst Theatre, Broadway |

| 1938 | Eye On the Sparrow | Philip Thomas | Vanderbilt Theatre, Broadway |

| 1938 | The Wind and the Rain | Charles Tritton | Millbrook Theatre, New York |

| 1938 | Dame Nature | Andre Brisac | Booth Theatre, Broadway |

| 1939 | The Mother | Tony | Lyceum Theatre, Broadway |

| 1940 | There Shall Be No Night | Erik Valkonen | Alvin Theatre, Broadway |

| 1941 | Out of the Frying Pan | Performer | Country Theater, Suffern |

| 1942 | Mexican Mural | Lalo Brito | Chain Auditorium, New York |

| 1942 | The Skin of Our Teeth | Henry | Plymouth Theatre, Broadway |

| 1944 | Our Town | George Gibbs | City Center, Broadway |

| 1944 | The Searching Wind | Samuel Hazen | Fulton Theatre, Broadway |

| 1945 | Foxhole in the Parlor | Dennis Patterson | Ethel Barrymore Theatre, Broadway |

| 1945 | You Touched Me | Hadrian | Booth Theatre, Broadway |

| 1954 | The Seagull | Constantin Treplev | Phoenix Theatre, Off-Broadway |

Radio

| Year | Programme | Episode | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1951 | Theatre Guild on the Air | The Glass Menagerie |

Awards and Nominations

| Year | Awards | Category | Project | Award | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1948 | Academy Awards | Best Actor | The Search | Nominated | |

| 1951 | A Place in the Sun | Nominated | |||

| 1953 | From Here to Eternity | Nominated | |||

| 1961 | Best Supporting Actor | Judgment at Nuremberg | Nominated | ||

| 1961 | British Academy Film Awards | Best Foreign Actor | Nominated | ||

| 1961 | Golden Globe Awards | Best Supporting Actor – Motion Picture | Nominated |

In 1960, Montgomery Clift received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. You can find it at 6104 Hollywood Boulevard.

See also

In Spanish: Montgomery Clift para niños

In Spanish: Montgomery Clift para niños

- List of actors with Academy Award nominations

- List of actors with two or more Academy Award nominations in acting categories

- List of LGBT Academy Award winners and nominees