F. D. Maurice facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

F. D. Maurice

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||||

| Born |

John Frederick Denison Maurice

29 August 1805 Normanston, Lowestoft, Suffolk, England

|

||||||

| Died | 1 April 1872 (aged 66) London, England

|

||||||

| Other names | Frederick Denison Maurice | ||||||

| Spouse(s) |

|

||||||

| Children |

|

||||||

| Relatives | Mary Atkinson Maurice (sister) | ||||||

|

|||||||

| Alma mater | |||||||

|

Notable work

|

The Kingdom of Christ (1838) | ||||||

| Scientific career | |||||||

| Institutions |

|

||||||

| Influences |

|

||||||

| Influenced |

Sir Percy Alden

Samuel Barnett Matilda Ellen Bishop Phillips Brooks James Baldwin Brown Lewis Carroll Lord Frederick Cavendish William Collins Emma Cons William Cunningham Percy Dearmer Frederic Farrar P. T. Forsyth T. H. Green Stewart Headlam Gabriel Hebert Octavia Hill Henry Scott Holland F. J. A. Hort William Reed Huntington J. R. Illingworth Herbert Kelly Charles Kingsley John Scott Lidgett John Llewelyn Davies Arthur Lyttelton George MacDonald William Augustus Muhlenberg H. Richard Niebuhr Conrad Noel Walter Pater Michael Ramsey Vida Dutton Scudder Henry Sidgwick Francis Herbert Stead William Temple Alec Vidler Brooke Foss Westcott Arthur Winnington-Ingram |

||||||

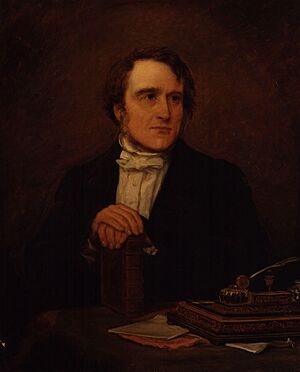

John Frederick Denison Maurice (born August 29, 1805 – died April 1, 1872) was an important English thinker. He was a Christian leader (called a theologian), a writer who published many books, and one of the people who started a movement called Christian socialism. This movement aimed to combine Christian beliefs with ideas about making society fairer for everyone. Since World War II, more and more people have become interested in his ideas.

Contents

Early Life and Education

John Frederick Denison Maurice was born in Normanston, Lowestoft, Suffolk, England, on August 29, 1805. He was the only son of Michael and Priscilla Maurice. His father was a preacher in a Unitarian church.

Family's Religious Journey

As Maurice grew up, his family went through big changes in their religious beliefs. This caused strong disagreements among them. Maurice later wrote that he felt "confused" by these different ideas. He felt drawn to the non-Unitarian side, not for religious reasons, but because Unitarianism seemed "incoherent and feeble" to his young mind.

His father was a very learned man and taught Maurice at home. Maurice was a good student who loved to read. He was serious and smart for his age, even then wanting to live a life of public service.

University Studies

In 1823, Maurice went to Trinity College, Cambridge to study civil law. At that time, only members of the official church could get a degree there. With his friend John Sterling, he helped start a discussion group called the Apostles' Club. He moved to Trinity Hall in 1825. In 1826, Maurice went to London to study law, then returned to Cambridge and earned a top degree in civil law in 1827.

Between 1827 and 1830, Maurice lived in London and Southampton. In London, he wrote for the Westminster Review and met John Stuart Mill, a famous thinker. He also helped edit a magazine called the Athenaeum. The magazine did not pay, and his father lost money, so the family moved to a smaller house in Southampton. Maurice joined them there.

A New Religious Path

While in Southampton, Maurice decided to leave his Unitarian beliefs and become a priest in the Church of England. John Stuart Mill said that Maurice and Sterling were like a "second Liberal" group, but with very different ideas from others. Maurice wrote articles that supported reformers and welcomed big changes in society. He also praised efforts to give more rights to Catholics in England.

In 1830, Maurice went to Exeter College, Oxford to prepare for becoming a priest. He was older and poorer than most students and kept to himself, studying hard. However, his honesty and intelligence impressed others. In March 1831, Maurice was baptized into the Church of England. After earning another degree in 1831, he worked as a private tutor in Oxford.

Becoming a Priest

In January 1834, Maurice became a deacon, which is the first step to becoming a priest. He was appointed to a church in Bubbenhall. At 28, he was older than most new priests and had more life experience. He had studied at two universities and been involved in London's literary and social scene. This, along with his dedication to reading, gave him a vast knowledge. He became a full priest in 1835.

Career and Marriages

Maurice's career can be split into two main parts: his busy and sometimes difficult years in London (1836–1866) and his more peaceful time in Cambridge (1866–1872).

Early Church Work

From 1834 to 1836, Maurice worked as an assistant priest in Bubbenhall. During this time, he started writing about "moral and metaphysical philosophy," which he continued to work on for the rest of his life. His novel, Eustace Conway, was published in 1834 and received praise from the poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge.

In 1836, he became a chaplain at Guy's Hospital in London, where he also taught students about moral philosophy. He stayed in this role until 1860. His public life really began during these years.

In June 1837, Maurice met Anna Eleanor Barton. They got engaged and married on October 7, 1837.

The Kingdom of Christ

In 1838, Maurice published The Kingdom of Christ, which became one of his most important books. He believed that the Christian "kingdom" could be seen through things like baptism, communion, creeds, church services, bishops, and the Bible. The book faced a lot of criticism when it was published, and this criticism followed Maurice throughout his career.

Life in London

Maurice was the editor of the Educational Magazine from 1839 to 1841. He believed that schools should be run by the church, not the government. In 1840, he became a professor of English literature and history at King's College, London. When the college added a theology department in 1846, he became a professor there too. That same year, he became a chaplain at Lincoln's Inn and left his job at Guy's Hospital.

From 1845 to 1853, Maurice was chosen to give important lectures by the Archbishops of York and Canterbury.

Maurice's first wife, Anna, died on March 25, 1845. They had two sons, one of whom, Frederick Maurice, later wrote his father's life story.

Starting Queen's College

During his time in London, Maurice helped start two important educational projects: Queen's College, London in 1848 and the Working Men's College in 1854.

In 1847, Maurice and other professors at King's College formed a group to help educate governesses (women who taught children in private homes). This led to the creation of Queen's College, and Maurice became its first leader. The college was allowed to give certificates to governesses and offer classes for women's education.

One of the first students at Queen's College who was inspired by Maurice was Matilda Ellen Bishop. She later became the first leader of Royal Holloway College.

On July 4, 1849, Maurice married again, this time to Georgina Hare-Naylor.

Leaving King's College

Maurice was removed from his teaching jobs at King's College. This happened because he was a leader in the Christian Socialist Movement and because some people thought his book Theological Essays (1853) had ideas that were not traditional. His earlier book, The Kingdom of Christ, had already caused strong criticism. When Theological Essays came out, the criticism grew even stronger, leading to his dismissal. Maurice refused to resign and demanded to be either cleared or fired. He was fired. To protect Queen's College from the controversy, Maurice also ended his connection with it.

Many people and his friends supported Maurice strongly. They respected him as a great spiritual teacher and wanted to protect him from his critics.

Founding the Working Men's College

Even after leaving King's College and Queen's College, Maurice continued to work for the education of working people. In February 1854, he created plans for a Working Men's College. He gathered enough support, and the college opened on October 30, 1854, with over 130 students. Maurice became the principal and actively taught and managed the college during his remaining years in London.

Maurice's teaching led to the Christian Socialism movement and the Society for Promoting Working Men's Associations. These groups aimed to help working people through cooperation.

During a time when there was fear of invasion in 1859–60, Thomas Hughes formed a volunteer army unit from the students of the Working Men's College. Maurice became their honorary chaplain in 1860.

In July 1860, despite the ongoing debates about his ideas, Maurice was appointed to lead the church of St Peter, Vere Street, Marylebone. He held this position until 1869.

Life at Cambridge University

On October 25, 1866, Maurice was chosen to be the Knightbridge Professor at Cambridge University. This was the highest academic position he achieved. He had mentioned his controversial books, Theological Essays and What is Revelation?, in his application. But at Cambridge, he was chosen almost unanimously and was warmly welcomed. People at Cambridge had no doubts about his traditional beliefs.

While teaching at Cambridge, Maurice remained the principal of the Working Men's College, though he visited less often. At first, he kept his church job in London, which meant a weekly train trip. When this became too tiring, he resigned in October 1869. In 1870, he accepted a position at St Edward's, Cambridge. This gave him a chance to preach to smart audiences with few other duties, though he received no pay.

In July 1871, Maurice also became a preacher at Whitehall in London. He was a person whom others would listen to, even if they disagreed with him.

Royal Commissioner

Despite his declining health, Maurice agreed in 1870 to serve on a Royal Commission. This group looked into the Contagious Diseases Act of 1871. He traveled to London for the meetings. The commission had 23 members, including politicians, clergy, and scientists.

Final Years

Even with a serious illness, Maurice continued to give his university lectures. He tried to get to know his students personally and finished his book Metaphysical and Moral Philosophy (two volumes, 1871–1872). He also kept preaching until February 1872. On March 30, he resigned from St Edward's. He was very weak and sad. On April 1, 1872, after receiving Holy Communion, he made a great effort to give a blessing, then became unconscious and died.

Different Views on Maurice's Ideas

Maurice once wrote that he was sad about the "conflicting opinions" of his time, which he felt "cramped our energies" and "killed our life." However, the term "conflicting opinions" perfectly described how people reacted to Maurice himself.

Maurice's writings, lectures, and sermons caused many different reactions. Julius Hare thought he was "the greatest mind since Plato". But John Ruskin believed Maurice was "puzzle-headed and indeed wrong-headed." John Stuart Mill felt that "more intellectual power was wasted in Maurice than in any other of my contemporaries."

Other examples of these different opinions include:

- Charles Kingsley called Maurice "a great and rare thinker."

- Aubrey Thomas de Vere said listening to Maurice was like "eating pea-soup with a fork."

- Matthew Arnold said Maurice was "always beating the bush with profound emotion, but never starting the hare."

One important writer who liked Maurice was Charles Dodgson, also known as Lewis Carroll. Dodgson wrote that he attended Maurice's sermons and liked them "very much."

However, others found his ideas hard to understand. M. E. Grant Duff wrote in his diary in 1855 that he had heard Maurice preach many times but "never carried away one clear idea."

John Henry Newman described Maurice as a man of "great power" and "great earnestness." But Newman found Maurice so "hazy" (unclear) that he "lost interest in his writings."

In the United States, a magazine in 1879 praised Maurice for his "broad catholicity, keenness of insight, powerful mental grasp, fearlessness of utterance and devoutness of spirit."

Social Activism

Maurice believed that seeking fairness in politics and economics was a key part of his Christian faith. He quietly took on the main burden of some of the most important social movements of his time.

Living in London, the struggles of poor people deeply affected him. Working men trusted him, even when they did not trust other church leaders. These men attended Bible classes and meetings led by Maurice, where he focused on moral improvement.

Christian Socialism

Maurice was influenced by the revolutionary movements of 1848. He believed that Christianity, rather than other ideas, was the only strong basis for rebuilding society.

Maurice disliked competition, seeing it as unchristian. He wanted to replace it with cooperation, which he felt showed Christian brotherhood. In 1849, Maurice and other Christian socialists tried to reduce competition by creating co-operative associations. He saw these groups as a modern way to apply early Christian ideas of sharing. They tried to start twelve cooperative workshops in London. Many of these did not make money, even with help from Edward Vansittart Neale. However, their efforts had lasting effects.

By 1854, there were many cooperative groups, including breweries, flour mills, and tailors. Some failed, but others lasted or were replaced by later cooperative movements.

Maurice's belief that society needed a moral and social renewal led him to Christian socialism. From 1848 to 1854, he was a leader of this movement. He insisted that "Christianity is the only foundation of Socialism." He also said that "true Socialism is the necessary result of a sound Christianity."

Maurice was seen as the spiritual leader of the Christian socialists. He was more interested in spreading the religious ideas behind the movement than in the practical details. He once wrote that his job as a theologian was "not to build, but to dig." He wanted to show that economics and politics needed a deeper foundation. He believed society should be renewed by finding its true order and harmony in God.

Society for Promoting Working Men's Associations

In early 1850, the Christian socialists started a working men's association for tailors in London, and then for other trades. To support this, they founded the Society for Promoting Working Men's Associations (SPWMA), with Maurice as a leader. At first, the SPWMA spread ideas through writings. Then, they started the Working Men's College. They believed educated workers were essential for successful cooperative groups. With more education, more associations succeeded.

A lasting achievement of the Christian socialists was influencing Parliament to pass a law in 1852. This law gave legal status to cooperative groups like working men's associations. The SPWMA was very active from 1849 to about 1853.

The SPWMA's original goal was to spread the idea of cooperation. They saw it as a way to apply Christian principles to business and industry. Their aim was to help working men and their families benefit fully from their labor.

In 1892–1893, representatives of "Co-operative Societies" told a Royal Commission that Christian socialists had greatly helped the "present cooperative movement" by developing the idea in the 1850s. They specifically named Maurice, Kingsley, Ludlow, Neale, and Hughes.

Legacy

Maurice left a legacy that many people would value. When he died on April 1, 1872, crowds followed his coffin to Highgate Cemetery. People from many different beliefs stood together, united by their sadness and deep respect for him. Tributes to Maurice came from churches, newspapers, loyal friends, and even his honest opponents.

Frederick Denison Maurice is remembered in the Church of England with a special day of commemoration on April 1.

Denison Road in Ealing, London, is named after him.

Personal Legacy

Maurice's close friends were deeply impressed by his spiritual character. His wife noted that whenever he was awake at night, he was "always praying." Charles Kingsley called him "the most beautiful human soul whom God has ever allowed me to meet with."

Maurice's life had "contradictory elements."

- He was a man of peace, yet his life was full of conflicts.

- He was very humble, but also argued strongly, sometimes seeming biased.

- He was very kind, but also criticized religious newspapers of his time harshly.

- He was a loyal churchman who disliked being called "Broad," yet he criticized church leaders.

- He had a kind and dignified manner, combined with a great sense of humor.

- He had a strong ability to imagine things that were not seen.

Teaching Legacy

As a professor at King's College and Cambridge, Maurice attracted many serious students. He gave them two things: knowledge from his wide reading, and more importantly, he taught them to ask questions, research, and think for themselves.

Written Legacy

Maurice's written legacy includes "nearly 40 volumes." These books hold "a permanent place in the history of thought in his time." His writings are clearly from a mind that was deeply Christian in all its beliefs.

Two of Maurice's books, The Kingdom of Christ (1838) and Moral and Metaphysical Philosophy (two volumes, 1871–1872), are famous enough on their own. But there are more reasons for his fame. In his life's work, Maurice was always teaching, writing, guiding, and organizing. He trained others to do similar work, giving them some of his spirit, not just his ideas. He brought out the best in others and never tried to force his views on them. With his opponents, Maurice tried to find common ground. No one who knew him personally could doubt that he was truly a man of God.

In The Kingdom of Christ, Maurice saw the true church as a united body. This body went beyond the differences and divisions of its individual members and groups. He believed the true church had six signs: baptism, creeds, set forms of worship, communion, an ordained ministry, and the Bible. Maurice's ideas were later reflected by William Reed Huntington and the Chicago-Lambeth Quadrilateral. The modern ecumenical movement also used Maurice's ideas from The Kingdom of Christ.

Interest in Maurice's Ideas

Interest in Maurice's many writings decreased even before he died. However, this period of neglect has now passed.

Since World War II, there has been a renewed interest in Maurice as a theologian. Many books have been published about him during this time.

Maurice is honored with a feast day on the liturgical calendar of the Episcopal Church (USA) on April 1.

Despite Maurice's dismissal from King's College, a special teaching position there, the F D Maurice Professorship of Moral and Social Theology, now honors his contributions to the college.

King's College also started "The FD Maurice Lectures" in 1933 to honor him. Maurice was a professor of English Literature and History (1840–1846) and then Theology (1846–1853) at the college.

Writings

Maurice's writings were the result of hard work. He usually woke up early and socialized with friends at breakfast. He would dictate his writings until dinner time. The manuscripts he dictated were carefully corrected and rewritten before being published.

His writings hold "a permanent place in the history of thought in his time." Many of these writings were first given as sermons or lectures.

Here are some of his notable works:

- Eustace Conway, or the Brother and Sister (a novel, 1834)

- The Kingdom of Christ (1838)

- The Lord's Prayer: Nine Sermons (1848)

- Moral and Metaphysical Philosophy (first an article in 1848, then expanded into volumes)

- Theological Essays (1853)

- The Prophets and Kings of the Old Testament (1853)

- The Doctrine of Sacrifice Deduced From the Scriptures (1854)

- Learning and Working (six lectures, 1855)

- The Gospel of St John (1857)

- What is Revelation? (1859)

- The Conscience: Lectures on Casuistry (1868)

- Social Morality: twenty-one lectures delivered in the University of Cambridge (1869)

- The Friendship of Books and Other Lectures (published after his death, 1873)

Images for kids