Freeman Field mutiny facts for kids

The Freeman Field mutiny was a series of important events that happened at Freeman Army Airfield in Seymour, Indiana, in 1945. During this time, African American officers of the 477th Bombardment Group tried to make an all-white officers' club open to everyone. This challenge led to 162 arrests of black officers. Three officers faced a court-martial (a military trial), and one was found guilty.

In 1995, the Air Force officially said that the actions of these African-American officers were right. They cleared the one conviction and removed official warnings from the records of 15 officers. Many historians see the Freeman Field mutiny as a key step toward ending segregation in the military. It also showed how people could use peaceful protest, called civil disobedience, to fight for equal rights.

Contents

Background to the Protest

Segregation in the Military

Before and during World War II, the United States military, like much of American society, was separated by race. This was called segregation. Most African-American soldiers were usually given support jobs instead of fighting roles. They also had very few chances to become officers or leaders.

In 1940, important African-American leaders like A. Philip Randolph and Walter White pushed for change. Because of their efforts, President Franklin D. Roosevelt allowed black men to train as fighter pilots in the United States Army Air Corps.

The Tuskegee Airmen

The first black flying unit, the 99th Fighter Squadron, trained in Tuskegee, Alabama. This is why all black military pilots became known as the "Tuskegee Airmen." Colonel Benjamin O. Davis Jr., the first African American to fly solo as an officer, led the 99th. This squadron fought in North Africa and Italy in 1943. In 1944, the 99th joined three other black squadrons to form the 332d Fighter Group.

The 477th Bombardment Group

African-American leaders continued to push for more opportunities. The Army then allowed black soldiers to train as bomber crew members. This opened up many more skilled combat jobs for them. On January 15, 1944, the 477th Bombardment Group (Medium) was created. Its job was to train African-American pilots to fly the B-25J Mitchell bomber in combat.

The 477th began training at Selfridge Field in Detroit, Michigan. The group faced low spirits because of segregation at Selfridge. The main officers' club there was closed to black officers. This was against Army rules, which said that officers' clubs should be open to all officers, no matter their race.

Moving to Kentucky

On May 5, 1944, the 477th was suddenly moved to Godman Field in Kentucky. This move might have been to avoid problems like the race riot that happened in Detroit the year before. At Godman Field, the officers' club was open to black officers. However, white officers used a different club at nearby Fort Knox.

The spirits of the 477th remained low. Godman Field was not good for training with the B-25 bombers. Also, black officers, even those who had fought in combat, were not being promoted to leadership roles. By early 1945, the 477th was ready for combat. It was scheduled to go into battle on July 1, which meant another move was needed. This time, they were sent to Freeman Army Airfield, a base that was perfect for the B-25 bombers.

The Protest at Freeman Field

The Events of April 5 and 6

The 477th started moving to Freeman Field on March 1, 1945. Soon, the black officers still at Godman Field heard that their commander, Colonel Selway, had created two separate officers' clubs at Freeman. Club Number One was for "trainees," who were all black. Club Number Two was for "instructors," who were all white.

Led by Second Lieutenant Coleman Young, who later became the mayor of Detroit, a group of black officers decided to challenge this segregation as soon as they arrived. On April 5, the last group of officers arrived at Freeman. They began to go in small groups to Club Number Two to get service.

The first group was turned away. Later, other groups were met by Lieutenant Joseph D. Rogers, who was armed and there on Colonel Selway's orders. When 19 officers, including Coleman Young, entered the club anyway and refused to leave, they were put under arrest. Seventeen more officers were arrested later that night. The next night, 25 more officers entered the club and were also arrested. In total, 61 officers were arrested during these two days. There was no physical violence from anyone during these events.

Base Regulation 85-2

After these events, an investigation suggested dropping the charges against most of the officers. Colonel Selway agreed and released 58 of them. However, he then created a new rule, Base Regulation 85–2, which he believed would legally enforce segregation.

To make sure all black officers knew about the new rule, Colonel Selway's deputy, Lieutenant Colonel John B. Pattison, gathered the trainees on April 10. He read them the regulation and asked them to sign a paper saying they understood it. No one signed.

Colonel Selway then set up a board with two black officers and two white officers. This board interviewed the officers who refused to sign. They gave them three choices:

- Sign the paper.

- Write and sign their own paper, without saying they understood the rule.

- Face arrest for disobeying a direct order during wartime. This was a very serious charge.

On April 11, 101 officers refused to sign and were placed under arrest.

Release of the Officers

The 101 arrested officers were sent back to Godman Field to wait for their trials. Meanwhile, many African-American organizations, labor unions, and members of Congress put pressure on the War Department to drop the charges. On orders from Army Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall, the 101 officers were released on April 23. However, a warning was placed in the official file of each arrested officer.

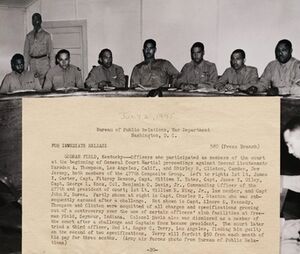

Three officers faced a general court-martial in July. Thurgood Marshall, who later became a justice on the U.S. Supreme Court, helped direct their defense. Theodore M. Berry, who later became mayor of Cincinnati, Ohio, was the lead defense lawyer.

Two officers were found not guilty. Lieutenant Roger Terry was found not guilty of disobeying an order. However, he was found guilty of "jostling" (lightly bumping) Lieutenant Rogers. He was fined $150, lost his rank, and was dishonorably discharged.

What Happened Next

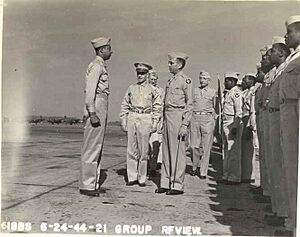

After the protest, the 477th Bombardment Group was moved back to Godman Field. Two of its four bomber squadrons were closed down. An all-black fighter squadron, the 99th FS, was added to the group. On June 21, 1945, Colonel Benjamin O. Davis Jr. became the commanding officer of the group. Black officers began to replace white officers in leadership roles. The group was supposed to finish training by August 31, but the war ended on August 14 when Japan surrendered.

The 477th Composite Group never fought in combat. It was made smaller when the war ended. In 1946, it moved to Lockbourne Field in Ohio. It was completely closed down in 1947. Sixty years later, in 2007, it was brought back as the 477th Fighter Group, the first Air Force Reserve unit to fly the F-22 Raptor jet.

In 1948, President Harry S. Truman issued Executive Order 9981. This order officially ended racial segregation in the United States Armed Services.

In 1995, the Air Force officially removed the warnings from the files of 15 officers involved in the Freeman Field protest. They also promised to remove the warnings for other officers who requested it. Roger Terry received a full pardon, got his rank back, and his fine was returned.

The events at Freeman Field, along with his own experiences, inspired the novel Guard of Honor. The author, James Gould Cozzens, won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction for this book in 1949.

See also

- African-American mutinies in the United States Armed Forces

- Battle of Bamber Bridge

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |