Fujiwara no Teika facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Fujiwara no Teika

|

|

|---|---|

A portrait of Teika

Attributed to Fujiwara no Nobuzane Kamakura period |

|

| Born | 1162 Kyoto, Heian Japan

|

| Died | September 26, 1241 (aged 78–79) Kyoto, Kamakura shogunate

|

| Occupation | Anthologist, calligrapher, literary critic, novelist, poet, scribe |

Fujiwara no Sadaie, better known as Fujiwara no Teika (1162 – September 26, 1241), was a famous Japanese poet and writer. He lived during the late Heian period and early Kamakura period. Teika was a master of the waka form, which is a traditional Japanese poem with 31 syllables in five lines.

His ideas about writing poetry were very important and were studied for many centuries. Teika came from a family of poets. His father, Fujiwara no Shunzei, was also a well-known poet. Teika became famous after the Retired Emperor Emperor Go-Toba noticed his talent. This started his long and successful career. Even though his relationship with Go-Toba later became difficult, Teika's family and poetic ideas continued to be very influential in Japanese poetry for hundreds of years.

Contents

Biography

Early Life and Family

Fujiwara no Teika was born in 1162. His family, the Fujiwara clan, was a noble family in Japan. However, Teika's branch of the family was not as powerful as others. They decided to focus on artistic skills, especially poetry, to gain respect in the court.

Teika's grandfather, Fujiwara no Toshitada, was a respected poet. His father, Fujiwara no Shunzei, was a very famous poet and a judge of poetry contests. Shunzei even put together an important collection of waka poems called the Senzai Wakashū. Teika's niece, known as Shunzei's Daughter, also became a respected poet. Teika sometimes asked her for advice.

Teika's Career and Challenges

Teika wanted to continue his father's legacy in poetry. He also hoped to improve his family's standing in the court. His life had many ups and downs, and he often faced illness. However, the support of the young and poetry-loving Retired Emperor Emperor Go-Toba helped Teika achieve great success.

Working with Emperor Go-Toba

In 1200, Retired Emperor Go-Toba announced a poetry contest. Retired Emperors often had more power after they stepped down from the throne because they were free from daily court duties. Go-Toba was very talented in many arts, including poetry.

He decided to hold two poetry contests. Poets had to write 100 waka poems on specific themes. These contests were very important. If a poet did well, their family would gain a lot of influence.

Teika, who was 38, saw this as a big chance. His career had not moved forward much. He was a "Lesser Commander of the Palace Guards" and had not been promoted in almost 10 years.

At first, Teika was not invited to the contest. This was because of his rivals, especially Suetsune, who disliked Teika. Teika was very angry about this. He wrote in his diary, Meigetsuki, that he believed Suetsune had bribed officials to keep him out.

However, Teika's father, Shunzei, spoke to Go-Toba on his son's behalf. Go-Toba respected Shunzei and agreed to let Teika join the contest. Teika worked very hard for over two weeks to finish his 100 poems. When he submitted them, Go-Toba was so excited that he read them right away.

One of Teika's poems, number 93 from this contest, was especially important. It helped him gain special permission to join the Retired Emperor's court. This was a big step for his career.

Here is an example of a poem Teika wrote when he felt overlooked for a promotion:

| Rōmaji | English |

|

toshi furedo |

Another year gone by |

Teika and Go-Toba worked closely together for a while. Go-Toba chose Teika to be one of the main compilers of the eighth Imperial Anthology of waka poetry, the famous Shin Kokinshū (finished around 1205). This was a huge honor. Teika had 46 of his own poems included in this collection.

Later, in 1232, Teika was chosen by Retired Emperor Emperor Go-Horikawa to compile the ninth Imperial Anthology, the Shinchokusen Wakashū. Teika was the first person ever to compile two Imperial anthologies by himself.

Disagreements with Go-Toba

Over time, Teika's good relationship with Go-Toba became strained. They had different ideas about how to write poetry, especially about how poems in a sequence should connect. Go-Toba liked very clear connections, while Teika's style was more varied.

Teika also showed his displeasure in small ways. For example, he refused to attend a celebration for the Shin Kokinshū in 1205. He said there was no historical example for such a party. Go-Toba then stopped including Teika in the ongoing revisions of the Shin Kokinshū.

Their disagreements grew. Go-Toba started to criticize Teika's poetry style, calling it too careless. Two main incidents led to a big break between them.

The first was in 1207. Go-Toba asked poets to write poems for 46 landscape screens. Teika's poem for one screen was rejected, not because it was bad, but because Go-Toba thought it was a "poor model." Teika was already annoyed by the short notice for the contest and started complaining about Go-Toba's poetic judgment.

The second incident happened in 1220. Teika was asked to join a poetry competition, but he refused. He said it was the anniversary of his mother's death. Go-Toba insisted, sending several letters. Teika finally came but brought only two waka poems. The second poem was a subtle but clear criticism of Go-Toba for forcing him to attend and for not promoting him enough.

Here is the poem Teika wrote:

| Rōmaji | English |

|

Michinobe no |

Under the willows |

Go-Toba saw this as a great insult. He banished Teika from his court for over a year.

Teika's Later Years

Luckily for Teika, political events changed things. In 1221, Go-Toba led a rebellion against the Kamakura shogunate but failed. He was then exiled for the rest of his life.

After Go-Toba's exile, Teika's standing improved. He was appointed to compile the ninth Imperial Anthology, the Shinchokusen Wakashū. This was a great honor. In 1232, at the age of 70, Teika was promoted to a high court rank.

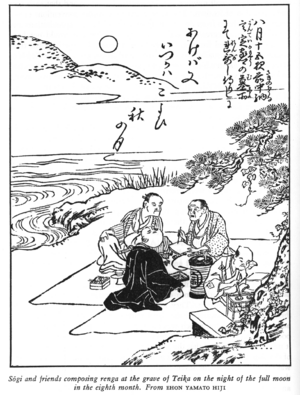

In his later years, Teika continued to refine his poetry style. He also studied and copied many old Japanese texts. He even experimented with a new type of linked verse called renga. Teika passed away in 1241 in Kyoto. He was buried at a Buddhist temple called Shokokuji.

Teika's Descendants and Legacy

One of Teika's sons, Fujiwara no Tameie, continued his father's poetic legacy. Tameie's descendants later split into three main poetry schools: the Nijō, Kyōgoku, and Reizei. These schools often disagreed about poetic styles, leading to many debates and rivalries for centuries. This shows just how important Teika's ideas were.

Poetic Achievements

Teika is famous for many things in Japanese literature.

Ogura Hyakunin Isshu

Teika chose the poems for the Ogura Hyakunin Isshu. This is a very famous collection of one hundred poems by one hundred different poets. It is still widely studied today. People believed this collection showed all the ideal types and techniques of waka poetry.

Manuscripts and Calligraphy

Teika made many copies of classic Japanese books. These included famous works like The Tale of Genji, The Tales of Ise, and the Kokin Wakashū anthology.

In his time, the old Japanese pronunciations were hard to understand. This made writing in kana (Japanese phonetic script) confusing. Teika studied old documents and figured out how to write kana correctly based on earlier systems. He created a clear system that was used until modern times. His copies of texts, known as Teika bon, were known for being very accurate and well-written.

Teika was also known for his unique and bold style of calligraphy (beautiful handwriting). His handwriting was so distinct that a modern computer font, "Kazuraki SPN," is based on it.

Poetic Style

Teika's poems were known for their elegance. He used old and classic images in new and fresh ways. For example, he might use images like pine trees or cherry blossoms in a unique setting.

Here is an example of his use of classic imagery:

| Japanese | Rōmaji | English |

|

高砂の |

Takasago no |

Tell it in the capital: |

Teika's poems often showed his ideals of yoen (ethereal beauty) and ushin (deep feeling). Yoen was about creating a sense of delicate and mysterious beauty. Ushin focused on expressing strong, true emotions. Teika's use of language to create a special atmosphere in his short poems was admired by later poets.

Here are some examples of his poems:

| Japanese | Rōmaji | English |

|

駒とめて |

Koma tomete |

There is no shelter |

|

|

||

|

こぬ人を |

Konu hito o |

Like the salt sea-weed, |

|

|

||

|

しかばかり |

Shika bakari |

So strong were |

See also

In Spanish: Fujiwara no Teika para niños

In Spanish: Fujiwara no Teika para niños

- Shikishi

- Reizei family

| William L. Dawson |

| W. E. B. Du Bois |

| Harry Belafonte |