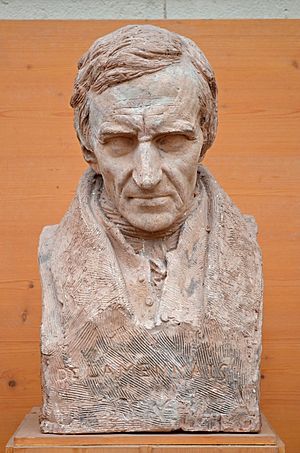

Félicité de La Mennais facts for kids

Félicité Robert de La Mennais (born June 19, 1782 – died February 27, 1854) was a French Catholic priest, thinker, and political writer. He was a very important person in France during the time after Napoleon. Lamennais is known as a pioneer of liberal Catholicism and social Catholicism. These ideas tried to mix Catholic faith with modern freedoms and social justice.

His ideas about religion and government changed a lot during his life. At first, he believed in reason alone. But his older brother, Jean-Marie, helped him see religion as a way to stop chaos and unfair rule. He disliked Napoleon because of laws that changed agreements between France and the Pope. Lamennais strongly disagreed with the idea that the government should control the Church. For a while, he was a strong supporter of the Pope's power over local churches (this is called ultramontane thinking).

Lamennais became a priest in 1817. That same year, he published an important book called Essai sur l'indifférence en matière de religion. In 1830, he started a newspaper, L'Ami de l'ordre, with his friends Montalembert and Lacordaire. He believed in ideas like more people being able to vote, the Church and state being separate, and freedom for everyone to think, learn, meet, and publish. His strong ideas made some of his friends distance themselves from him. In 1833, he left the Church. The next year, he published Paroles d'un croyant, which Pope Gregory XVI criticized for its ideas.

He was elected to represent Paris in the French assembly. His plan for a new Constitution was not accepted because it was too radical. He passed away in Paris in 1854.

Contents

Early Life and Family Background

Félicité Robert de la Mennais was born in Saint-Malo, France. His family was involved in international shipping and trade.

Grandfathers and Their Influence

His grandfather, Louis-François Robert de La Mennais (1717–1804), started a trading and shipping company in Saint-Malo. This business involved preparing ships for trade, providing supplies, and even cannons. It was a job that needed courage and daring.

His other grandfather, Pierre Lorin (1719–1799), was a lawyer in Paris. He also represented the king's power in the Saint-Malo area. He cared deeply about people and worked to help those suffering from poverty. He suggested setting up charity offices in every town. He bought a place called La Chésnaie in 1781. Félicité later started a school of religious thought there.

Childhood and Education

Félicité was one of five children. His mother, Gatienne Lorin, died in 1787 when he was only five years old. Because of this, his uncle, Robert des Saudrais, raised him and his brother, Jean-Marie, at La Chênaie.

Félicité did not like strict rules. His uncle would sometimes lock him in the library. There, he spent many hours reading books by famous thinkers like Rousseau and Pascal. This helped him gain a lot of knowledge.

The French Revolution had a big impact on Lamennais. His family even hid priests who refused to follow the new government's rules for the Church. Secret Masses were sometimes held in the dark at La Chênaie.

First Writings and Religious Path

Lamennais was often sick and very sensitive. The events of the French Revolution made him feel sad and worried. At first, he believed only in reason. But his brother Jean-Marie and his own studies helped him see the importance of faith and religion.

In 1808, he wrote a book called Réflexions sur l'état de l'église en France. He published it without his name. His brother Jean-Marie helped with the ideas for this book. It suggested a religious revival and stronger Church organization. It also promoted an ultramontane spirit, meaning strong support for the Pope's authority. Napoleon's police thought the book was dangerous and tried to stop it.

In 1809, Lamennais translated a spiritual book into French. In 1811, he became a professor of mathematics at a religious college in Saint-Malo. His brother, who was already a priest, had founded this college. When the government closed the school, Félicité went back to La Chênaie.

In 1814, he and his brother wrote another book. It strongly criticized Gallicanism, which was the idea that the French king or government had power over the Church in France. They believed the government should not interfere in Church matters.

Becoming a Priest and Important Works

Exile and Ordination

Lamennais welcomed the return of the French monarchy in 1814. He saw King Louis XVIII as a way to bring back religious values. When Napoleon returned to power for a short time (the Hundred Days), Lamennais escaped to London. He worked there helping children of poor immigrants. After Napoleon was finally defeated, he returned to Paris. Lamennais believed religion could fix the chaos and unfairness caused by the revolution. He studied theology and became a subdeacon in 1816. He considered joining the Jesuits but decided to become a regular priest instead. He was ordained a priest on March 9, 1817.

Essay on Indifference

The first part of his major work, Essai sur l'indifference en matière de religion (Essay on Indifference in Matters of Religion), came out in 1817. This book made him famous across Europe. He argued that if the government did not care about religion, it would lead to a lack of faith. He wanted to bring back the Catholic Church's power that it had before the Revolution. He believed that relying only on personal judgment in religion, philosophy, and politics had led to people losing their faith. He said that the Church's authority, based on God's revelation, was the only hope for improving European societies.

Three more parts of the book were published between 1818 and 1824. Some bishops and supporters of the monarchy did not like it, but younger priests strongly supported it. Even Pope Leo XII approved of his work. Lamennais visited Rome at the Pope's request and was even offered to become a cardinal, but he refused.

Lamennais also published religious books, like a popular French version of The Imitation of Christ. He also published Guide du premier âge and Journée du Chrétien. A publishing company he started to spread these books failed, which caused him financial problems.

Political Ideas and Activism

After returning to France, Lamennais became very active in politics. He wrote for a newspaper called Le Conservateur littéraire. However, when the leader of the government, the Comte de Villèle, strongly supported absolute monarchy, Lamennais stopped supporting him. He then started two new newspapers, Le Drapeau blanc and Le Mémorial catholique. He also wrote a pamphlet criticizing a law about sacrilege in 1825.

Supporting the Pope and Democracy

Lamennais moved back to La Chênaie and gathered a group of followers, including Montalembert and Lacordaire. He strongly supported ultramontanism, wanting to fight against the government's control over the Church. In his 1828 book, Les Progrès de la revolution et de la guerre contre l'église, he completely gave up his support for kings. From then on, he argued for a type of democracy where religious principles guided the government.

Lamennais and his friends found inspiration in a Catholic movement in Belgium. Belgium, which was mostly Catholic, separated from the Netherlands in 1830 and became a constitutional monarchy. The archbishop there found a way to use the new freedoms to help the Church grow.

In 1830, Lamennais started a newspaper called L'Ami de l'ordre, with the motto "God and Liberty." His social ideas became even stronger. The newspaper pushed for more local control, more people being able to vote, and the separation of church and state. It also demanded universal freedom of thought, education, assembly, and the press. He believed that how people worshipped should be open to criticism and improvement, but only under the Church's spiritual authority, not the government's.

His ideas were opposed by some bishops but supported by younger priests. However, he lost some support when he said priests should not be paid by the state. With Montalembert's help, he created an organization to defend religious freedom. This group had agents all over France who watched for violations of religious freedom. Because of his strong views, the newspaper faced many challenges.

Meeting the Pope

Even though the French government and Church leaders pressured him, Pope Gregory XVI preferred not to make a big issue of Lamennais's ideas. However, Lamennais, Montalembert, and Lacordaire stopped their newspaper and went to Rome in 1831 to get the Pope's approval. The Archbishop of Paris had warned Lamennais that his ideas were unrealistic.

After much difficulty, they met the Pope, but only if they did not talk about their political ideas. A powerful Austrian leader, Metternich, pushed for Lamennais's ideas to be condemned. A few days later, they received a letter from a cardinal, advising them to leave Rome. The letter suggested that the Pope understood their intentions but wanted the matter left open for now.

Lacordaire and Montalembert left immediately. Lamennais stayed longer, but his hopes were crushed when the Pope wrote a letter criticizing the Polish revolution. The Pope believed the Polish rebels were trying to weaken the Russian Tsar, who supported Catholic kings in France. While in Germany, Lamennais received a letter from the Pope, Mirari vos (1832). This letter criticized religious freedom in general and some of Lamennais's ideas, though it did not mention him by name. After this, Lamennais and his friends announced they would stop publishing their newspaper and close their organization out of respect for the Pope.

Leaving the Church and Later Life

Lamennais went back to La Chênaie. He shared his anger and political beliefs only through letters. The Vatican then demanded that he fully accept the Pope's letter, Mirari vos. Lamennais refused to agree without conditions. In December 1833, he gave up his duties as a priest and stopped practicing Christianity.

In May 1834, Lamennais wrote Paroles d'un croyant (Words of a Believer). This book was a collection of short, powerful statements. It criticized the existing social order, which he called a conspiracy of kings and priests against the people. This book showed his complete break with the Church. In a letter called Singulari nos (June 25, 1834), Pope Gregory XVI condemned the book as "small in size, [but] enormous in wickedness."

Paroles was inspired by a Polish book about the Polish nation. Lamennais's Paroles marked his shift towards a Christian socialism. This idea combined Christian values with socialist goals and inspired many socialists of his time.

He was imprisoned for a time in 1836.

Lamennais was increasingly left by his friends. In 1837, he published Les Affaires de Rome, where he explained his side of the story regarding his relationship with Pope Gregory XVI.

After this, Lamennais wrote many articles and published pamphlets like Le Livre du peuple (1837) and De l'esclavage moderne (1839). In these writings, he supported the idea that the people should have power and criticized society and the government. After publishing Le Pays et le gouvernement (1840), he was censored and imprisoned for a year in 1841.

From 1841 to 1846, Lamennais published four volumes of Esquisse d'une philosophie, a book about deep philosophical ideas. This work showed how much he had moved away from Christianity. He also published Les Evangiles, a French translation of the Gospels with his own notes.

In 1846, Lamennais published Une voix de prison, which he wrote while in prison.

Involvement in the Second Republic

Lamennais supported the Revolution of 1848. He was elected to represent Paris in the assembly that would create a new constitution. He wrote a plan for a Constitution, but it was rejected because it was too radical. After this, he mostly stayed quiet during the assembly sessions.

He also started two newspapers, Le Peuple constituant and La Révolution démocratique et sociale, which promoted radical revolutionary ideas. Both newspapers quickly stopped being published. He was also named president of a group called the Société de la solidarité républicaine. He remained a representative until Napoleon III's coup in 1851. This event made him feel sad and isolated again.

Final Years and Passing

After 1851, he worked on translating Dante's Divine Comedy. He refused several offers to return to the Church. He died in Paris in 1854 and was buried in a common grave at Père Lachaise Cemetery. There were no funeral rites, but many political and literary admirers mourned him.

|

See also

In Spanish: Félicité Robert de Lamennais para niños

In Spanish: Félicité Robert de Lamennais para niños

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |