Gas giant facts for kids

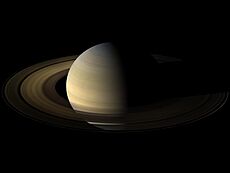

A gas giant is a huge planet made mostly of hydrogen and helium. These planets are much bigger than Earth. In our Solar System, we have two gas giants: Jupiter and Saturn.

For a long time, all very large planets were called "giant planets." But scientists later realized that Uranus and Neptune are quite different. They are now called ice giants. Ice giants are made mostly of heavier, icy materials, not just gas. This makes them a special type of giant planet.

Jupiter and Saturn are mostly hydrogen and helium. Only a small part of their mass (about 3 to 13 percent) comes from heavier elements. Scientists believe they have a very deep atmosphere of hydrogen gas. Deeper down, this gas becomes super compressed. Below that, there's a layer of liquid metallic hydrogen. At the very center, they likely have a hot, rocky core.

The outer parts of their atmospheres have many layers of clouds. These clouds are mostly made of water and ammonia. The metallic hydrogen layer is a huge part of these planets. It's called "metallic" because the extreme pressure turns hydrogen into something that can conduct electricity, like a metal. The cores of gas giants are incredibly hot (around 20,000 K) and under immense pressure. We are still learning exactly what they are like.

Contents

What Are Gas Giants?

The name gas giant was first used by science fiction writer James Blish in 1952. It was meant for all giant planets. However, the name can be a bit confusing. This is because most of the material inside these planets is not actually in a gaseous form like air on Earth. The pressure is so high that the matter is beyond its critical point. This means there is no clear difference between a liquid and a gas.

Even so, the name "gas giant" stuck. Planetary scientists often use "rock," "gas," and "ice" as simple terms. They use these to describe the main ingredients of planets. "Gases" usually mean hydrogen and helium. "Ices" refer to water, methane, and ammonia. "Rocks" mean silicates and metals. So, since Uranus and Neptune are mostly "ices," they are called ice giants. Jupiter and Saturn, being mostly "gases," are the true gas giants.

Planets Beyond Our Solar System

Scientists have found many gas giants orbiting other stars. These are called exoplanets. Some of these exoplanets are very different from Jupiter and Saturn.

Cold Gas Giants Far Away

A cold gas giant made mostly of hydrogen can be much more massive than Jupiter. But it might not be much larger in size. If a gas giant is more than about 500 times the mass of Earth (or 1.6 times Jupiter's mass), its own gravity will make it shrink. This is because the material gets squeezed together more tightly.

Gas giants can also create their own heat. This is due to something called Kelvin–Helmholtz heating. This process makes them radiate more energy than they get from their star.

Tiny Gas Planets: Gas Dwarfs

Not all hydrogen planets are as huge as Jupiter or Saturn. Some gas planets are much smaller. These are sometimes called "gas dwarfs" or mini-Neptunes. Planets closer to their star or smaller in size can lose their atmospheres faster. This happens through a process called hydrodynamic escape.

A gas dwarf is a planet with a rocky core. This core is surrounded by a thick layer of hydrogen, helium, and other light gases. These planets typically have a total radius between 1.7 and 3.9 times that of Earth.

One of the smallest known exoplanets that is likely a gas planet is Kepler-138d. It has the same mass as Earth. But it is 60% larger. This means it has a very low density, suggesting it has a thick gas envelope. A small gas planet can still look like a gas giant in size if it has the right temperature.

Wild Weather on Gas Giants

The weather on gas giants is driven by heat rising from deep inside the planet. This heat often escapes through giant thunderstorms. These storms then create smaller swirling patterns. These patterns can grow into huge storms, like Jupiter's Great Red Spot.

On Earth, lightning and the water cycle are linked to powerful thunderstorms. When water vapor condenses, it releases heat. This heat pushes air upwards. This "moist convection" helps separate electrical charges in clouds. When these charges reunite, we see lightning. So, lightning tells us where strong convection is happening. Even though Jupiter has no oceans, moist convection seems to work in a similar way there.

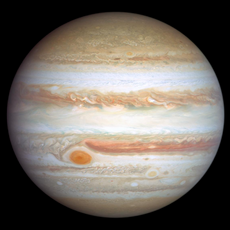

Jupiter's Famous Great Red Spot

The Great Red Spot (GRS) is a massive storm in Jupiter's southern half. It is a powerful anticyclone, which means it's a high-pressure system. It spins counterclockwise at speeds of about 430 to 680 kilometers per hour. The Great Red Spot is known for its strength. It can even absorb smaller storms on Jupiter.

Scientists think the red color comes from special organic compounds called tholins. These tholins are found on the surfaces of various planets. They form when exposed to UV radiation. On Jupiter, storms and air currents pull these tholins up into the atmosphere. It is believed that these tholins get trapped in the Great Red Spot, giving it its distinctive red color.

Raining Helium on Saturn and Jupiter

On gas giants, helium can condense and fall as liquid helium rain. This happens on Saturn at certain pressures and temperatures. Here, helium does not mix well with the liquid metallic hydrogen. In these areas, the denser helium forms droplets. These droplets then fall deeper into the planet's center. This process releases heat, which adds to Saturn's energy.

The helium rain continues until it reaches a warmer area. There, it dissolves back into the hydrogen. Because Jupiter and Saturn have different total masses, this helium rain might be more common on Saturn. This helium condensation could explain why Saturn gives off more heat than expected. It also helps explain why there is less helium in the atmospheres of both Jupiter and Saturn.

See also

In Spanish: Gigante gaseoso para niños

In Spanish: Gigante gaseoso para niños

- List of gravitationally rounded objects of the Solar System

- List of planet types

- Hot Jupiter

- Ice giant

- Kepler-1704b

- Brown dwarf

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |