George Tyrrell facts for kids

Quick facts for kids George Tyrrell |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Orders | |

| Ordination | 1891 |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 6 February 1861 Dublin, United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland |

| Died | 15 July 1909 (aged 48) Storrington, United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland |

| Denomination | Roman Catholic, Latin Church |

| Occupation |

|

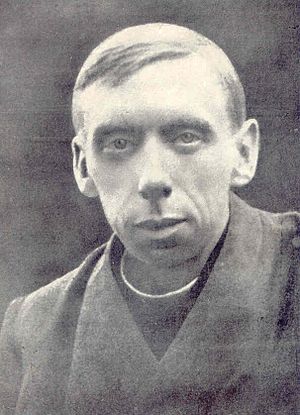

George Tyrrell (born February 6, 1861 – died July 15, 1909) was an Anglo-Irish Catholic priest. He was also a very famous and sometimes debated scholar. Tyrrell changed from being an Anglican (a type of Christian) to a Catholic. He joined the Jesuit order in 1880.

Tyrrell tried to mix Catholic ideas with new science and culture. This made him important in a big discussion about "modernism" in the Catholic Church. This debate started in the late 1800s. Because of his views, he was removed from the Jesuit Order in 1906. He was also excommunicated (kicked out of the Church) in 1908.

Contents

George Tyrrell's Early Life

George Tyrrell was born in Dublin, Ireland, on February 6, 1861. His father, who was a journalist, died just before George was born. George had a cousin named Robert Yelverton Tyrrell, who was a famous scholar. A childhood accident caused George to become deaf in his right ear. His family often had to move because they did not have much money.

Education and Religious Path

Tyrrell grew up as an Anglican. Around 1869, he went to Rathmines School near Dublin. From 1873, he studied at Midleton College. This school was connected to the Church of Ireland. However, his mother found it hard to pay the school fees. So, he left school early.

In 1876 and 1877, he studied on his own. He hoped to win a scholarship to study Hebrew at Trinity College, Dublin. But he failed the test twice. Around 1877, he met Robert Dolling, an Anglo-Catholic priest. Dolling had a big impact on Tyrrell. In August 1878, Tyrrell started teaching at Wexford High School. In October, he began studying at Trinity College. He hoped to become an Anglican minister.

Becoming a Jesuit Priest

In the spring of 1879, Tyrrell went to London. He worked for the Saint Martin's League, a mission group led by Dolling. One day, Tyrrell visited St Etheldreda's, a Catholic church. He was deeply moved by the Catholic Mass. He later wrote that it felt like "the old business" carried on "in the old ways."

Joining the Jesuits

Tyrrell decided to become a Catholic. He was welcomed into the Catholic Church in 1879. He immediately wanted to join the Jesuit order. But his leader told him to wait a year. During that year, he taught at Jesuit schools in Cyprus and Malta. He joined the Jesuits in 1880. He then went to a special training house called Manresa House.

In 1882, his teacher thought Tyrrell should leave the Jesuits. He felt Tyrrell was too "stubborn" in his thinking. Tyrrell also did not like some Jesuit traditions. But Tyrrell was allowed to stay. He later said he felt more suited to the Benedictine way of life.

Studies and Ordination

After taking his first vows, Tyrrell went to Stonyhurst College. There, he studied philosophy as part of his Jesuit training. After Stonyhurst, he returned to Malta to teach for three years. Then, he went to St Beuno's College in Wales. Here, he began his studies in theology. He became a priest in 1891.

After working as a priest for a short time, Tyrrell returned for more training. In 1893, he worked in Oxford. Then he moved to St Helens, Merseyside, where he was very happy as a Jesuit. About a year later, he was sent back to Stonyhurst to teach philosophy. Here, Tyrrell started to disagree with his leaders. They had different ideas about how to teach philosophy.

Pope Leo XIII had said that Catholic schools should teach a philosophy based on Saint Thomas Aquinas. Tyrrell admired Aquinas. But he thought the way Jesuits taught it was too narrow. He believed they were teaching only one specific view of Aquinas's ideas.

In 1896, Tyrrell moved to a Jesuit house in London. There, he learned about the ideas of Maurice Blondel. He was also influenced by Alfred Loisy's studies of the Bible. Tyrrell became good friends with Friedrich von Hügel in 1897. While in London, Tyrrell wrote articles for a Jesuit magazine called The Month.

Expulsion and Excommunication

In 1906, George Tyrrell was asked to give up his new ideas. He refused. Because of this, he was removed from the Jesuit order. The head of the Jesuits, Franz X. Wernz, made this decision. Tyrrell was the only Jesuit removed from the order in the 20th century until 1969.

In 1907, the Pope spoke out against "modernism." This happened first in a document called Lamentabili sane exitu. Then, it happened again in a longer letter called Pascendi dominici gregis. These actions sealed Tyrrell's fate. Tyrrell wrote two letters to The Times newspaper. In these letters, he strongly criticized the Pope's letter.

Because he publicly rejected Pascendi, Tyrrell was also not allowed to receive the sacraments. This was like a "minor excommunication" from the Church. Tyrrell said that the Church's ideas were based on old science and psychology. He felt these ideas seemed strange to modern people. He also said that the Pope's letter mixed up Catholic beliefs with just one type of old philosophy. He believed the letter tried to show that "modernists" were not Catholic. But he felt it only showed they were not followers of that old philosophy.

Tyrrell's case was handled by the Cardinal Secretary of State, Rafael Merry del Val. He worked closely with Bishop Amigo.

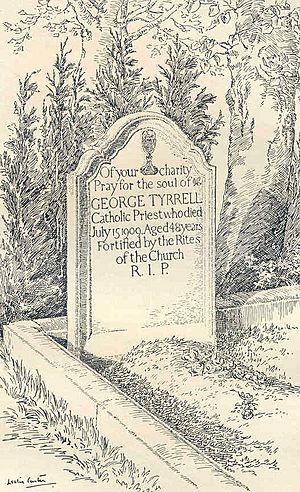

Death and Burial

Tyrrell spent his last two years mostly in Storrington. He received the last rites (a special prayer for the dying) before he died in 1909. However, he still refused to change his "modernist" views. Because of this, he was not allowed to be buried in a Catholic cemetery.

His friend, a priest named Henri Brémond, was at the burial. He made the sign of the cross over Tyrrell's grave. As a result, Bishop Amigo temporarily stopped Fr. Bremond from performing his priestly duties. Some people at the time blamed the disagreements between modern Catholic thinkers and the Vatican on Cardinal Merry del Val's "unbending and old-fashioned attitude."

Selected Writings

- Nova et Vetera: Informal Meditations, 1897

- Hard Sayings: A Selection of Meditations and Studies, Longmans, Green & Co., 1898

- External Religion: Its Use and Abuse, B. Herder, 1899

- The Faith of the Millions 1901

- Lex Orandi: or, Prayer & Creed, Longmans, Green & Co., 1903

- Lex Credendi: A Sequel to Lex Orandi, Longmans, Green & Co., 1906

- Through Scylla and Charybdis: or, The Old Theology and the New, Longmans, Green & Co., 1907

- A Much-Abused Letter, Longmans, Green, and Co., 1907

- Medievalism: A Reply to Cardinal Mercier, Longmans, Green, and Co. 1908

- The Church and the Future, The Priory Press, 1910

- Christianity at the Cross-Roads, Longmans, Green and Co., 1910

- Autobiography and Life of George Tyrrell, Edward Arnold, 1912

- Essays on Faith and Immortality, Edward Arnold, 1914

Articles by George Tyrrell

- "The Clergy and the Social Problem," The American Catholic Quarterly Review, Vol. XXII, 1897.

- "The Old Faith and the New Woman," The American Catholic Quarterly Review, Vol. XXII, 1897.

- "The Church and Scholasticism," The American Catholic Quarterly Review, Vol. XXIII, 1898.

See also

In Spanish: George Tyrrell para niños

In Spanish: George Tyrrell para niños

| Chris Smalls |

| Fred Hampton |

| Ralph Abernathy |