Gore-McLemore Resolutions facts for kids

The Gore-McLemore Resolutions were special proposals in the United States Congress in early 1916. They warned American citizens not to travel on armed ships belonging to countries fighting in World War 1. These proposals came as Germany was getting ready to use its submarines more often. This was also after sad events like the sinking of the Lusitania.

The resolutions showed that some Democrats in Congress disagreed with President Woodrow Wilson about Germany's submarine warfare. But in the end, most Democrats supported the President. The McLemore Resolution in the House of Representatives and the Gore Resolution in the Senate were both quickly put aside after they were introduced.

Contents

What the Gore Resolution Said

Here is a shorter version of the Gore Resolution (S. Con. Res. 14 from the 64th Congress, February 25, 1916):

Therefore, be it Resolved by the Senate, the House of Representatives concurring, that it is the sense of the Congress... that all persons owing allegiance to the United States should... avoid traveling as passengers upon any armed vessel of any belligerent power... and it is the further sense of Congress that no passport should be issued or renewed... for purpose of travel upon any such armed vessel...

This means Congress felt that Americans should not travel on armed ships of warring nations. They also thought that the government should not give passports for such travel.

Why These Resolutions Were Proposed

Since World War 1 started in mid-1914, the United States tried to stay neutral. This meant not taking sides in the war. However, the US had strong economic ties with the Allied powers, especially Great Britain. They traded goods and gave loans. Many American leaders also worried about what a German victory would mean for the Americas.

Germany's Submarine Warfare Policy

The situation became more difficult when Britain blocked Germany from getting supplies in early 1915. In response, Germany declared the waters around Britain a war zone. They started a policy of unrestricted submarine warfare. This meant their U-boat submarines would attack any ship, even neutral passenger or merchant vessels, without warning.

Over the next few months, President Wilson and his team tried to find a solution. They wanted to make it safer for neutral ships. But their efforts to get Britain and Germany to agree did not work.

Dangerous Ship Sinkings

Several dangerous events happened in 1915 because of Germany's submarine policy. Ships like the Falaba, the Lusitania, and the Arabic were sunk. Americans died in these attacks. Even though President Wilson worked for peace, by late 1915, it seemed like war was possible. This was because Americans kept losing their lives from German U-boat attacks. When the 64th Congress met in January 1916, a main concern was how to deal with the submarine issue.

The Journey of the Resolutions in Congress

Disagreements Between Congress and the President

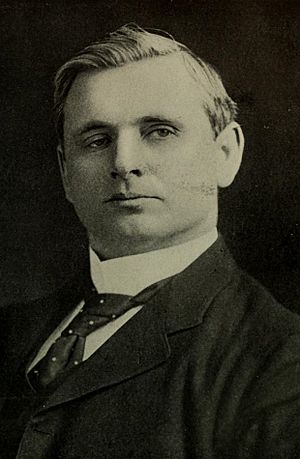

On January 5, 1916, Senator Thomas P. Gore from Oklahoma introduced two bills. He was strongly against war. These bills aimed to control how American citizens traveled on ships of warring nations. Senator Gore believed Americans should avoid these ships. He thought this would lower the risk of war between the US and Germany. Many senators worried that more American deaths would force the US into war. During these debates, it became clear that Congress and President Wilson had different ideas.

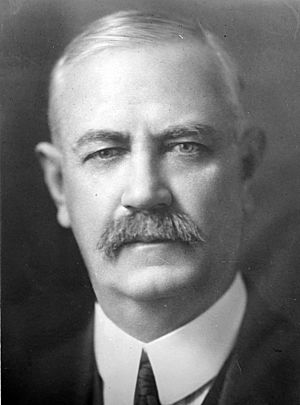

On February 8, 1916, Germany announced a new rule. They would treat all armed merchant ships as warships and sink them starting in March. Secretary of State Robert Lansing said Germany would be responsible for any American lives lost. But he also said there was no plan to warn Americans not to travel on these ships. This made Congress very upset. Many new bills and resolutions were proposed, including those by Senator Gore and Representative Atkins Jefferson McLemore from Texas.

President Wilson's Stance

Because Congress was so angry, Senator William Stone, who led the Foreign Relations committee, met with President Wilson on February 21, 1916. Wilson was firm. He said Americans had the right to travel on armed merchant ships. He warned that he would cut off diplomatic ties with Germany if they kept sinking ships and killing Americans. He also told Congress to stop getting involved in foreign policy. This worried anti-war Democrats like Senators Gore and Stone. They felt it was even more important to warn Americans off armed ships.

On February 24, President Wilson wrote a letter to Senator Stone. He repeated his commitment to protecting American rights. He said that if Americans were stopped from traveling freely, it would make America seem weak. The next day, Wilson met with House leaders. He again said he would not accept any limits on America's rights. He told them that solving the submarine problem needed the American people to support him. By this time, many in Congress started to support President Wilson again. But Senator Gore still held his anti-war views.

The McLemore Resolution in the House

After Germany's announcement, many anti-war Democrats in the House of Representatives disagreed with President Wilson. Representative A. Jefferson McLemore introduced his resolution (H. Res. 147) on February 22, 1916. It asked the President to warn Americans not to travel on armed merchant ships. The resolution went to the House Foreign Affairs Committee.

However, the anti-war Democrats misjudged how much support they would get. The chairman of the Foreign Affairs Committee, Representative Henry Flood, told the Wilson administration he would delay the McLemore resolution. The House Speaker, Champ Clark, agreed. On February 25, some representatives from Georgia even prepared their own resolution to support Wilson. They wanted to stop McLemore's resolution if it moved forward. Newspapers also called on Congress to support the President, which was met with applause.

By the end of February, President Wilson had gained strong support from Democrats in Congress. Support for the McLemore resolution faded. On March 7, 1916, the House voted 276-142 to put the McLemore resolution aside. Most House Democrats voted to table it, especially in the South.

The Gore Resolution in the Senate

Senator Gore introduced his resolution, S. Con. Res. 14, on February 25, 1916. It was read into the Congressional record. Gore's resolution was slightly different from McLemore's. It spoke directly to US citizens and said the Secretary of State should stop issuing passports in some cases. Gore probably knew his resolution would not pass. By then, pro-Wilson members of Congress were already turning the tide against such resolutions.

President Wilson was so sure of victory that on February 29, he called for a vote on both the Gore and McLemore resolutions. This was a risky move. If the resolutions passed, it could hurt his diplomatic efforts. But Wilson wanted to show foreign countries, especially Germany, that he had the support of Congress. This would make the US stronger in future talks.

On March 3, 1916, the Gore resolution was debated. Senator Gore said he acted based on a report that President Wilson had met with leaders. He said Wilson suggested the US and Germany might soon be at war. Gore said Wilson thought the US "entering the war now might be able to bring it to a conclusion." Gore was talking about the "Sunrise Conference." His account was quite accurate, but other members of Congress strongly denied that Wilson wanted war.

Just before the vote on March 3, Senator Gore added new words to his resolution: "The sinking by a German submarine, without notice or warning, of an armed merchant vessel of her public enemy, would constitute a just and sufficient cause of war between the United States and the German Empire." This change surprised many members of Congress. They could not discuss the new wording before the vote. The new language actually changed the resolution's meaning. A vote to put the resolution aside now meant a vote against war with Germany. This was Gore's goal as an anti-war Congressman. In the end, the Senate voted to table the Gore resolution 68-14. Senator Gore himself voted to table his own resolution.

What Happened Next

Even though there was disagreement about submarines in early 1916, by March, most Democrats in Congress supported President Wilson. Wilson had pushed for party unity before the 1916 election, which he won by a small margin. Another important submarine attack happened on the Sussex in April 1916. But the Sussex pledge that followed helped calm tensions with Germany for the rest of the year regarding submarine policy.

As World War 1 continued, the disagreement between Senator Gore and President Wilson grew. Gore remained against the war and against getting involved in other countries' affairs. He disagreed with many parts of Wilson's foreign policy. Gore's views on the draft and the League of Nations made him unpopular with the press in Oklahoma. Gore later wrote that the Gore-McLemore resolution "was the first link in the chain of events that led to my defeat" in the 1920 Senate race. But he believed the US was "speeding headlong into war."

In April 1917, Congress voted on a resolution declaring war on Germany. It passed both houses with a huge majority. Senator Gore was not there for the vote in the Senate. But he later said he would have voted against the declaration of war to keep his campaign promises. Representative McLemore voted against the declaration of war in the House.

| William L. Dawson |

| W. E. B. Du Bois |

| Harry Belafonte |