Great French Wine Blight facts for kids

The Great French Wine Blight was a terrible plant disease in the mid-1800s. It destroyed many vineyards in France and badly hurt the country's wine business. An aphid (a tiny insect) from North America caused this blight. It traveled across the Atlantic Ocean in the late 1850s.

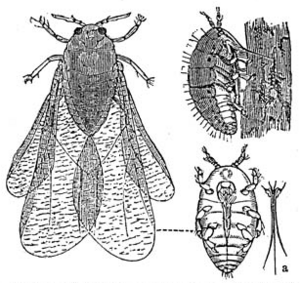

Scientists still discuss the exact type of aphid. But most agree it was a species called Daktulosphaira vitifoliae, also known as grape phylloxera. France was hit the hardest, but the blight also damaged vineyards in other European countries.

No one is sure how the Phylloxera aphid got to Europe. American grapevines had been brought to Europe many times before. This was for experiments or for trying out grafting methods. People did not think about bringing pests with them. The Phylloxera bug probably arrived around 1858. It was first officially seen in France in 1863, in a region called Languedoc. Some people believe these pests became a problem only after steamships were invented. Steamships made the trip across the ocean faster. This allowed pests like the Phylloxera to survive the journey.

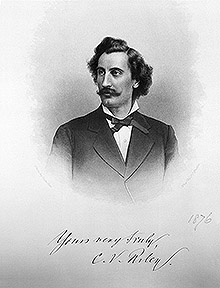

Eventually, scientists found a solution. Jules-Emile Planchon discovered that Phylloxera caused the blight. Charles Valentine Riley then confirmed Planchon's idea. Two French wine growers, Leo Laliman and Gaston Bazille, suggested a plan. They proposed that European grapevines should be grafted onto American roots. These American roots were naturally resistant to the Phylloxera bug. Many French wine growers did not like this idea at first. But most had no other choice. This method worked very well. Bringing back the lost vineyards was a slow process. But eventually, the wine business in France returned to normal.

Contents

How the Blight Started

The aphid that caused so much damage in France was first noticed in the 1500s. French settlers in Florida, America, tried to grow European grapevines. These vines were called Vitis vinifera. But their vineyards failed. Later attempts with similar vines also failed. The settlers did not know why this happened.

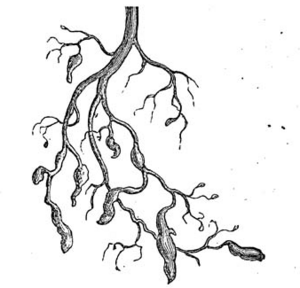

Today, we know that a type of North American grape phylloxera caused these early vineyards to fail. The Phylloxera bug injects a poison. This poison causes a disease that quickly kills European grapevines. The settlers did not notice the aphids at first. This was even though there were many of them.

It became well known among the settlers that their European vinifera vines would not grow in American soil. So, they started growing native American grape plants instead. There were some exceptions. Vinifera vineyards grew well in California before the aphids reached there.

The Phylloxera Bug

People had many ideas about why the phylloxera bug was not seen as the cause of the disease. Most of these ideas have to do with how the insect feeds. The grape phylloxera has a special mouthpart called a proboscis. It has a tube to inject its deadly poison. It also has a feeding tube to suck in sap and food from the vine.

When the poison damages the vine's roots, the sap pressure drops. Because of this, the Phylloxera quickly pulls out its feeding tube. It then looks for another food source. So, if someone dug up a sick or dying vine, they would not find Phylloxera bugs on its roots.

How the Bug Reached Europe

For a few centuries, Europeans experimented with American vines and plants. Many types were brought from America without any rules. People did not think about pests coming along. Jules-Emile Planchon, a French biologist, identified the Phylloxera in the 1860s. He believed that more American vines came to Europe between 1858 and 1862. This accidentally brought Phylloxera to Europe around 1860.

Others say the aphid did not enter France until about 1863. The invention of steamships might have played a part. Steamships were faster than sailing ships. This meant the Phylloxera bugs had a better chance of surviving the shorter ocean trip.

The Blight's Impact

First Signs of Trouble

The first known attack by Phylloxera in France happened in 1863. It was in the village of Pujaut, in the Gard area of Languedoc. The wine makers there did not see the aphids. Just like the French settlers in America, they only noticed a mysterious disease. This disease was harming their vines. The wine growers said the disease "reminded them sadly of 'consumption'" (tuberculosis). The blight quickly spread across France. But it took several years to find out what was causing it.

Widespread Damage

Over 40% of France's grapevines and vineyards were destroyed. This happened over 15 years, from the late 1850s to the mid-1870s. The French economy was hit very hard by the blight. Many businesses closed, and wages in the wine industry were cut by more than half. Many people also moved to places like Algiers or America.

The production of cheap raisins and sugar wines caused problems for the French wine business. These problems threatened to last even after the blight was gone. The damage to the French economy was estimated to be over 10 billion Francs. This was a huge amount of money at the time.

Finding the Cause

Research into the disease began in 1868. Grape growers in Roquemaure, near Pujaut, asked for help. They contacted the agricultural society in Montpellier. The society formed a committee. It included botanist Jules Émile Planchon, local grower Felix Sahut, and the society's president, Gaston Bazille.

Sahut soon noticed that the roots of dying vines were full of "lice." These tiny bugs were sucking sap from the plants. The committee named the new insect Rhizaphis vastatrix. Planchon talked to French insect experts Victor Antoine Signoret and Jules Lichtenstein. Signoret suggested renaming the insect Phylloxera vastatrix. This was because it looked like Phylloxera quercus, which attacked oak leaves.

In 1869, an English insect expert, John Obadiah Westwood, suggested something. He thought an insect that had attacked grape leaves in England around 1863 was the same one. He believed it was the same insect harming grapevines in France. Also in 1869, Lichtenstein suggested that the French insect was an American "vine louse." This louse had been identified in 1855 by American expert Asa Fitch. Fitch had named it Pemphigus vitifoliae.

However, there was a problem with these ideas. French grape lice were only known to attack a vine's roots. But American grape lice were only known to attack its leaves. Charles Valentine Riley, an American insect expert, had been following the news from France. He sent samples of American grape lice to Signoret. In 1870, Signoret concluded they were the same as the French grape lice.

Meanwhile, Planchon and Lichtenstein found vines with damaged leaves. They moved lice from these leaves to the roots of healthy vines. The lice attached themselves to the roots, just like other French grape lice. Also in 1870, Riley discovered that American grape lice spent winter on American grapevines' roots. The insects damaged these roots, but less than they damaged French vines. Riley repeated Planchon and Lichtenstein's experiment. He used American grapevines and American grape lice, and got similar results. This proved that the French and American grape lice were the same.

Even so, for three more years, many people in France argued. They said Phylloxera was not the cause of the vine disease. Instead, they thought sick vines simply got infested with Phylloxera. So, they believed Phylloxera was just a result of the "real" disease, which they still needed to find.

Despite this, Riley had found American grape varieties that were very resistant to Phylloxera. By 1871, French farmers started to import them. They also began to graft French vines onto the American rootstock. (Leo Laliman had suggested importing American vines as early as 1869. But French farmers did not want to give up their traditional varieties. Gaston Bazille then suggested grafting traditional French vines onto American rootstock.)

However, importing American vines did not completely solve the problem. Some American grape varieties struggled in France's chalky soils. They still died from Phylloxera. Through trial and error, American vines were found that could grow in chalky soils. Meanwhile, insect experts worked to understand the strange life cycle of Phylloxera. This project was finished in 1874.

The Solution: Grafting

Many growers tried their own methods to fix the problem. They used chemicals and pesticides, but nothing worked. In desperation, some growers put toads under each vine. Others let their chickens roam free, hoping they would eat the insects. None of these methods were successful.

After Charles Valentine Riley confirmed Planchon's theory, Leo Laliman and Gaston Bazille suggested an idea. They thought that if vinifera vines could be joined with aphid-resistant American vines, the problem might be solved. This joining would happen through grafting. Thomas Volney Munson was asked for help. He provided native Texan rootstocks for grafting. Because of Munson's help, the French government honored him in 1888. They sent a group to Denison, Texas to give him the French Legion of Honor.

Another grape expert, Hermann Jaeger from Neosho, Missouri, was also very important. He helped save the French vineyards. Jaeger, working with Missouri state insect expert George Hussman, had already grown vines that resisted the pest. In fact, some of the rootstock types T.V. Munson developed in Texas were grafts. They used the strong Neosho hybrids Jaeger had created in Missouri. Jaeger sent 17 train carloads of his resistant rootstock to France. In 1893, Jaeger was also awarded the French Legion of Honor. This was for his help to France's grape and wine industries.

The grafting method was tested and it worked! French wine growers called this process "reconstitution." The cure for the disease caused a big split in the wine industry. Some, called "chemists," rejected grafting. They kept using pesticides and chemicals. Those who became grafters were known as "Americanists" or "wood merchants." After grafting proved successful in the 1870s and 1880s, the huge job of "reconstituting" most of France's vineyards began.

The Prize Money

The French government had offered over 320,000 Francs. This was a reward for anyone who could find a cure for the blight. Leo Laliman was reportedly the first to suggest using the resistant American rootstock. He tried to claim the money. But the French government refused to give it to him. They said he had not cured the blight, but only stopped it from happening. However, there might have been other reasons. Laliman was not trusted by some important people. Many also thought he was the one who first brought the pest to France.

The Blight Today

There is still no true cure for the Phylloxera bug or the disease it causes. It remains a big threat to any vineyard not planted with grafted rootstock. Only one European grapevine is known to resist Phylloxera. This is the Assyrtiko vine. It grows on the volcanic Greek island of Santorini. However, some think its resistance comes from the volcanic ash in the soil, not the vine itself.

There are still some vines that were never grafted or destroyed by phylloxera. This includes some owned by the Bollinger wine company.

See Also

In Spanish: Gran plaga de la filoxera para niños

In Spanish: Gran plaga de la filoxera para niños

| George Robert Carruthers |

| Patricia Bath |

| Jan Ernst Matzeliger |

| Alexander Miles |