Greater prairie-chicken facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Greater prairie-chicken |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Male displaying in Illinois, USA | |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Galliformes |

| Family: | Phasianidae |

| Genus: | Tympanuchus |

| Species: |

T. cupido

|

| Binomial name | |

| Tympanuchus cupido (Linnaeus, 1758)

|

|

| Subspecies | |

|

T. c. attwateri |

|

|

|

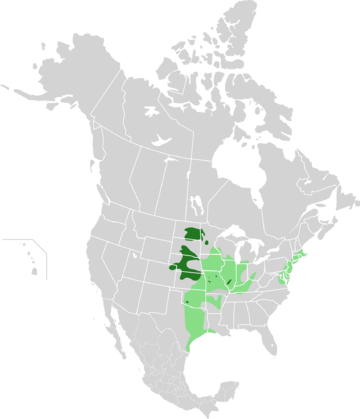

| Distribution map of the greater prairie-chicken. Pale and dark green: pre-settlement Dark green: current year-round |

|

| Script error: The function "autoWithCaption" does not exist. | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Tetrao cupido Linnaeus, 1758 |

|

Script error: No such module "Check for conflicting parameters".

The greater prairie-chicken (Tympanuchus cupido) is a large bird from the grouse family. It's sometimes called a "boomer." These birds once lived all over North America. Sadly, they are now very rare. This is mostly because they have lost their homes, the open grasslands. People are working hard to protect the small groups of prairie-chickens that are left. One of the most amazing things about these birds is their special mating dance, which makes a booming sound.

Contents

What Does a Prairie-Chicken Look Like?

Both male and female greater prairie-chickens look like large chickens. They have strong, rounded wings and short, rounded tails.

Adult birds are about 43 centimeters (17 inches) long. They weigh between 700 and 1200 grams (1.5 to 2.6 pounds). Their wingspan is about 69.5 to 72.5 centimeters (27 to 28.5 inches).

Male vs. Female Birds

Male greater prairie-chickens have bright orange, comb-like feathers above their eyes. They also have long, dark feathers on their heads that they can raise up. A special round, orange patch on their neck can inflate like a balloon when they are showing off.

Female birds have shorter head feathers. They do not have the male's bright orange eye combs or the orange neck patch.

Types of Prairie-Chickens

There are three types, or subspecies, of the greater prairie-chicken:

- The heath hen (Tympanuchus cupido cupido) used to live along the Atlantic coast. This type is now completely extinct.

- Attwater's prairie-chicken (T. c. attwateri) is an endangered type. It only lives in coastal Texas.

- The greater prairie-chicken (T. c. pinnatus) is the most common type. However, it now lives in only a small part of where it used to be found.

Where Do Prairie-Chickens Live and What Do They Eat?

Greater prairie-chickens love wide-open grasslands called prairies. They especially like tallgrass prairies that are not disturbed by people. They can live in areas where farms are mixed with grasslands, but they prefer more natural areas.

Their main food is seeds and fruit. In the summer, they also eat green plants and insects. These insects include grasshoppers, crickets, and beetles. These birds once lived all across the oak savanna and tallgrass prairie areas.

Protecting Prairie-Chickens

The greater prairie-chicken almost disappeared in the 1930s. This was due to too much hunting and losing their homes. In Illinois, there were millions of prairie-chickens in the 1800s. They were popular birds for hunting.

Like many prairie birds, they have lost a lot of their habitat. Now, they are close to extinction. In 2019, there were only about 200 wild birds left in Illinois. They now live only on small pieces of protected grassland.

Across North America, their numbers have dropped a lot. There are now only about 500,000 individuals left. In May 2000, Canada listed the greater prairie-chicken as gone from its country. This was confirmed again in 2009. However, people still sometimes see them in parts of Alberta, Saskatchewan, and southern Ontario.

Helping Populations Grow

In states like Iowa and Missouri, there used to be hundreds of thousands of prairie-chickens. Now, their total numbers have fallen to about 500. The Missouri Department of Conservation has started a program to help. They are bringing prairie-chickens from Kansas and Nebraska. They hope this will help the birds repopulate Missouri and reach 3,000 birds.

Central Wisconsin is home to about 600 prairie-chickens. This is down from 55,000 in 1954, when hunting was stopped. Today, over 30,000 acres are managed by the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources. This land is kept as good habitat for the greater prairie-chicken. Birdwatchers from all over the world visit Wisconsin in April. They come for the Central Wisconsin Prairie Chicken Festival, which started in 2006.

What Harms Prairie-Chickens?

Losing their habitat is the biggest threat to prairie-chicken populations. More than 95% of all tallgrass prairie in the United States has been turned into farmland. Turning natural grasslands into farms is very bad for these birds.

Studies have shown that prairie-chicken hens avoid building nests or raising their young near power lines and busy roads. They also stay away from communication towers and rural farms.

Other Dangers

Studies have found that some smaller predators eat prairie-chicken eggs. These include striped skunks, raccoons, and opossums. When these predators were removed, nesting success greatly improved. When larger predators like bears and wolves are missing, the numbers of these smaller predators can grow. This then reduces the number of prairie-chickens.

Non-native common pheasants also cause problems. They sometimes lay their eggs in prairie-chicken nests. This is called nest parasitism.

Some groups of prairie-chickens became very small. This led to a problem called a population bottleneck. This means they had less variety in their genes. This made it harder for their young to survive. In Illinois, wildlife managers helped by bringing in birds from other areas. This helped to improve the genetic health of the small groups.

See also

In Spanish: Gallo de las praderas grande para niños

In Spanish: Gallo de las praderas grande para niños

- Lesser prairie chicken

- Lekking