Green Corn Rebellion facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Green Corn Rebellion |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Theater of World War I | |||||

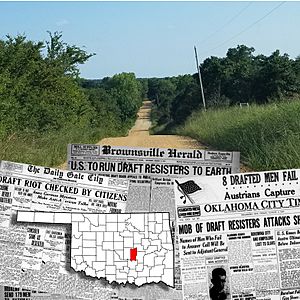

The Green Corn Rebellion was centered in rural Seminole County in southeastern Oklahoma. |

|||||

|

|||||

| Belligerents | |||||

| Pontotoc Rebels | |||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||

| Working Class Union (?) | Woodrow Wilson | ||||

| Strength | |||||

| 800 to 1000? | Thousands | ||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||

| 3 killed 450 arrested |

|||||

The Green Corn Rebellion was a small armed protest in rural Oklahoma in August 1917. It happened because many people, including European-Americans, tenant farmers, Seminoles, Muscogee Creeks, and African-Americans, did not want to join the military draft for World War I.

The name "Green Corn Rebellion" came from the rebels' supposed plan. They wanted to march across the country, eating "green corn" (young corn) along the way. However, someone told the authorities about their plans. The rebels met a group of armed townsmen. Shots were fired, and three people died. After the event, many people were arrested. The Socialist Party of America, which was popular in the area, was blamed for trying to start a revolution. This incident was later used as an excuse to take action against the Industrial Workers of the World and the Socialist Party across the country.

Contents

Why the Rebellion Started: The Draft and World War I

On April 6, 1917, US President Woodrow Wilson asked the US Congress to declare war on Germany. Congress agreed quickly. This decision meant the United States would join World War I.

To get enough soldiers, the US government decided to start a military draft. This meant young men would be required to join the military. On May 18, 1917, a draft law was passed. It said that all eligible young men had to sign up for the draft on June 5, 1917. Most young men accepted this, even if they did not like it.

On July 20, 1917, Newton D. Baker, the Secretary of War, drew numbers to choose who would have to serve. Many groups, like the Socialist Party of America, were against the war and the draft. They held meetings and handed out flyers. The Socialist Party believed the war was wrong and told workers around the world not to support it.

Oklahoma's Unique Situation

Oklahoma was a new state in 1917, having joined the United States in 1907. However, it already had a strong history of people wanting big changes. Many poor tenant farmers in southeastern Oklahoma were drawn to the ideas of the Socialist Party. They hoped these ideas would make their lives better.

In the 1916 election, the Socialist Party received a lot of votes in Seminole County and Pontotoc County. This showed how many people in the area supported their ideas.

The Working Class Union

The Socialist Party was not the only group active there. In 1916, a group called the "Working Class Union (WCU)" was formed by radical tenant farmers. They claimed to have as many as 20,000 members in Eastern Oklahoma alone. This group believed in helping workers and also in self-defense. They were against the draft.

Many tenant farmers were young. About 76% of Oklahoma farmers under 24 rented their land. These young farmers often struggled financially. They faced high interest rates from stores and large debts to landlords. The land in Oklahoma was not very fertile, so farmers had to work very hard to grow crops. Life was tough, and many felt hopeless. The draft would take away young men needed for farm work, which could cause farms to fail and families to lose everything. There were no other jobs or welfare to help them.

The WCU was a secret society. Its members sometimes rode at night and used violence against those they opposed. For example, in 1915, dynamite was used against vats used for "cattle dipping." This was a process to kill ticks on cattle, but some farmers felt the chemicals were harmful to the animals. This led to anger and conflict between the rural farmers and the townspeople.

Townspeople believed that the Socialists and the WCU were working together to start a revolution.

The Muscogee Creek Nation and the Gathering

During this time, the Muscogee Creek Nation was largely controlled by a small group of mixed-blood Creek and white individuals. August 3 was also the end of the Muscogee Creek Green Corn Ceremony.

In early August 1917, before the rebellion, many African-American, European-American, and Native American men met at a farm near Sasakwa. They gathered at Roasting Ear Ridge to plan a march to Washington, DC, to try and end the war.

The Rebellion Begins

The Green Corn Rebellion began on August 2, 1917. A sheriff from Seminole County, Frank Grall, and a deputy, Bill Cross, were ambushed near the Little River. After this, groups of rebels cut telephone lines and burned railroad bridges.

On August 3, two weeks after the draft lottery, an armed group gathered where Pontotoc, Seminole, and Hughes Counties meet. The Working Class Union seemed to have encouraged this uprising. One newspaper reported that the WCU called its supporters to arms with a message:

Now is the time to rebel against this war with Germany, boys. Boys, get together and don't go. Rich man's war. Poor man's fight. The war is over with Germany if you don't go and J.P. Morgan & Co. is lost. Their great speculation is the only cause of the war.

Historians believe that the draft threatened to ruin families by taking away young men needed for farming. Many poor farmers also believed that the war was just a way for rich capitalists to make money.

The country people saw the military draft as an attack on their rights. They rebelled to stop the government from taking their sons.

The March and Its End

About 800 to 1000 rebels, mostly from old American families, gathered by the South Canadian River. They planned to march east and live off the land. They would eat roasted "green corn" and barbecued beef. They hoped to meet thousands of others who felt the same way. Together, they would march on Washington, DC, overthrow President Wilson, get rid of the Draft Act, and end the war.

However, an informer quickly told the local authorities about their plans. A group of armed townsmen was formed and went to the river to meet the rebels. The rebellion ended quickly. When the rebels saw the townsmen coming, they fired a few shots and then ran away. This was the end of their open resistance. The incident was over in a few hours, and many participants were arrested.

What Happened Next

In total, three people died during the Green Corn Rebellion in August 1917. One of them was Clifford Clark, a black tenant farmer. Nearly 450 people were held in connection with the event. About 266 of them were released without being charged. Charges were brought against 184 people. About 150 of these were found guilty or pleaded guilty. They received jail or prison sentences ranging from 60 days to 10 years. Those believed to be leaders received the longest sentences.

Most of them were released early or pardoned. However, five men were still in a federal prison in Leavenworth, Kansas, in February 1922.

The "rebellion" was used to criticize the Socialist Party of Oklahoma. Even though the event was mostly unplanned and not directly caused by the Socialist Party, they were blamed. This was one of many events that weakened the socialist movement in America and led to the First Red Scare, a time of fear about communism.

The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) was also blamed, even though they had no part in the Green Corn Rebellion. The WCU had formed partly because the IWW did not allow tenant farmers to join. Still, the IWW was blamed for the WCU's actions. The Green Corn Rebellion was used to justify further actions against the IWW across the country.

An elderly Seminole-Muscogee Creek woman told a historian that her uncle was imprisoned after the rebellion. She said that the Native Americans had encouraged their white and black neighbors to rise up. They believed that fighting, no matter the outcome, would inspire future generations. This was a long-standing Native American tradition of fighting and telling the story so that future generations would continue the struggle.

A fictional story about the rebellion can be found in William Cunningham's novel, The Green Corn Rebellion, published in 1935. The book was re-released in 2010. Sam Marcy, who started the Workers' World Party, saw the Green Corn Rebellion as a great example of working-class people fighting against war. He wrote about it in his 1985 book, "The Bolsheviks and War."

In 2017, the 100-year anniversary of the Green Corn Rebellion was remembered with media stories and a website created to collect historical information and new ideas about the event.

Images for kids

-

The Little River, near Sasakwa, Oklahoma, the site of an ambush of a Seminole County sheriff and deputy.

| Percy Lavon Julian |

| Katherine Johnson |

| George Washington Carver |

| Annie Easley |